Related parties debt remission

AGENCY DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

This Regulatory Impact Statement (RIS) has been prepared by Inland Revenue.

It addresses the question of whether the remission of debt between certain associated persons should continue to be asymmetrically taxed and, if not, how this current asymmetric treatment should be resolved.

Currently, the remission of debt between certain associated persons such as a parent company and its subsidiary means the subsidiary (the debtor) is taxed on the value of any debt remitted and the parent (the creditor) is denied a deduction for the debt remitted – the tax outcome is asymmetric. However, there is no real net economic income to tax – neither the value of the group of companies nor the ownership of the subsidiary has changed.

The design of the policy options in this RIS was informed by public feedback on initial proposals contained in the February 2015 Officials’ Issues Paper Related parties debt remission, and extensive informal discussions with the representatives from the tax community before and after the release of the paper. This feedback also confirmed the problem definition and provided guidance as to the direction of the analysis. The major outstanding issue in the issues paper was the question of what to do with debt associated with inbound investment. The issues paper considered the various arguments and left this particular question open to submissions. This matter is addressed in this RIS.

This project will, at least at the margin, make it easier for New Zealand subsidiaries of foreign companies to deduct payments for interest expense. This reduces the New Zealand tax base. The tax policy work programme project on thin capitalisation will help counter this by further considering New Zealand’s thin capitalisation rules as a result of the BEPS (OECD’s base erosion and profit shifting project).

There are no other key gaps, assumptions, or dependencies concerning the analysis.

The policy options will not impose additional costs on businesses, impair private property rights, restrict market competition, reduce the incentives on businesses to innovate and invest, or override fundamental common law principles (as referenced in Chapter 3 of the Legislation Advisory Committee Guidelines).

Jim Gordon

Policy Manager, Policy and Strategy

Inland Revenue

18 August 2015

STATUS QUO AND PROBLEM DEFINITION

1. This Regulatory Impact Statement (RIS) covers options for improving the debt remission rules in the Income Tax Act 2007.

Debt remission

2. Debt remission is the extinguishing of a debtor’s liability by operation of law or forgiveness by the creditor.

3. Debt can be remitted when the debtor:

- is discharged from making remaining payments;

- is insolvent or liquidated;

- enters into a deed of composition with its creditors that results in full remission; or

- has no obligation to make payments when, because of the passage of time, the debt is irrecoverable or unenforceable.

4. The Income Tax Act 2007 provides that the remission of debt causes the debtor to derive remission income under the base price adjustment (BPA) of the financial arrangement rules. The purpose of the debt remission rules is to recognise the fact that the forgiveness of a debt increases the wealth of the debtor.

Bad debt deductions

5. When the debtor and creditor are not associated persons and the creditor is in the business of holding or dealing in such debt, the creditor generally obtains a deduction for a bad debt under the bad debt rules. This means that a debt remission transaction has a symmetrical result; there is income to one party, and a deduction to the other party.

Associated persons

6. The Tax Acts have a usual presumption that taxpayers deal with each other at arm’s length. However, where two taxpayers are connected this presumption falls away and there are a number of particular tax rules that govern transactions between the two taxpayers. Examples of associated persons include:

- Two companies where, directly or indirectly, a single shareholder owns 50% or more of the companies;

- Companies and non-corporate shareholders who own 25% or more of them;

- Partners and their partnerships; and

- Close relations (e.g. brothers).

Associated persons cannot claim bad debt deductions

7. An associated person creditor is denied a bad debt deduction for the principal of a debt.

8. This associated persons bad debt deduction rule has been in place in one form or another since the financial arrangements rules were introduced in 1986. A shareholder has a choice of investing in a company or partnership by way of debt or equity. The reason for the associated person bad debt prohibition is that allowing a deduction for a bad debt would bias investment towards debt, as all gains from the investment will be able to be attributed to the equity investment only, whereas losses could be attributed over both equity and debt resulting in a one sided tax deduction from the amount that can be attributed to the debt.

Debt remission between associated persons is therefore asymmetrical, despite no increase in wealth

9. The combination of these two sets of rules – the debt remission income rules and the denial of bad debt deductions for associated persons rules, means that a debt remission between these two parties results in an asymmetric result. There is income to one party, but the other party cannot claim a deduction. There is often, however, no change in wealth of the group of associated persons, and therefore no economic transaction that ought to be taxed.

10. The asymmetric taxation outcome is best illustrated in the wholly-owned group of companies scenario. The parent company (the creditor) lends to a subsidiary (the debtor) and sometime later this loan is remitted (perhaps because the subsidiaries balance sheet needs shoring up). The debt remission is an intra-group transaction that does not change the wealth or ownership of the group in any way. The debtor derives taxable debt remission income but the creditor is denied a bad debt taxation deduction.

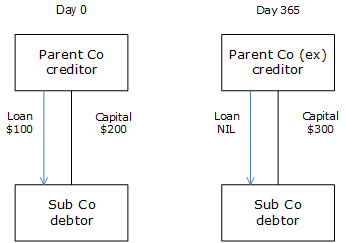

11. The example below illustrates the core problem. On Day 0 Parent Co lends $100 to Sub Co. On day 365 the debt is remitted so that the capital of Sub Co is increased to $300 and the loan balance reduces to zero. The result is the same if the debt is capitalised.

Example 1

Capitalising debt, rather than remitting debt

12. Until recently, rather than remitting debt, and facing this asymmetric result, some taxpayers choose to capitalise debt instead on the basis that this did not result in asymmetric taxation outcomes. Capitalising debt is literally the conversion of debt into equity or capital.

Choosing to capitalise, rather than remit, debt might amount to tax avoidance

13. A recent Inland Revenue legal interpretation has concluded that if this debt capitalisation does not result in an effective change of ownership of the debtor this could be tax avoidance and, if so, is to be reconstructed as a remission of the debt.

14. The main concerns with this interpretation (the status quo) applying to these types of debt capitalisations are:

- Doubt about the certainty of the result – in what circumstances would debt capitalisation be interpreted as tax avoidance; and

- More complexity and cost to avoid the inappropriate asymmetric taxation outcome – much more complicated and subtle restructuring would be needed to avoid the taxation consequences and this would be economically inefficient.

Scale of the problem

15. Inland Revenue could potentially seek to review past debt capitalisations and argue that at least some of them are tax avoidance. This could result in a windfall tax gain for the Government in respect of transactions where there is no economic income. For example, officials are aware of two loans each totalling about $750 million of debt previously advanced by non-resident owners that have been capitalised. Given the likelihood of a legislative solution Inland Revenue is not presently considering these transactions.

16. The legal interpretation potentially affects entities which range in size from the mom and pop partnership or look through company, to large corporate groups of companies. Although debt capitalisation is not an everyday transaction, feedback from tax specialists suggests that it occurs reasonably frequently.

Secondary problem

17. There is a further issue concerning inbound investment and its associated debt. Interest expense on inbound debt is a key Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) concern and the OECD is working on thin capitalisation proposals. Allowing cross border debt remission to be tax free means that the thin capitalisation rule would be relied upon even more to govern debt and interest levels on inbound debt.

18. This is because allowing debt remission will, at the margin, make it easier for New Zealand subsidiaries of overseas companies to deduct interest expense. This reduces the New Zealand tax base. The tax policy work programme project on thin capitalisation will counter this by helping to ensure that only appropriate interest deductions are claimed by these New Zealand subsidiaries.

Problem definition

19. The root cause of this problem is not debt capitalisation itself. Rather it is the existence of an asymmetric result when associated persons perform a debt remission transaction and there is no increase in wealth of the group. Debt capitalisation is only relevant because of the legal interpretation that says that sometimes it can be tax avoidance, and if so is reconstructed as debt remission income.

20. The status quo is not sustainable as the asymmetric taxation outcome where there is net change of wealth or ownership is inappropriate. Further, it potentially creates complexity and cost for taxpayers and does not help New Zealand’s reputation as being a reasonable, stable and certain place to do business.

OBJECTIVES

21. The current tax policy framework is framed around a broad-base low-rate (BBLR) concept – that is, taxation should be fair and equitable and should, to the extent possible, be based on taxing economic income. This framework is important as it provides taxpayers with certainty as to outcome.

22. The asymmetric taxation outcome in situations where there is no economic change in wealth or ownership does not accord with this BBLR framework. The only way to correct this situation is to amend the tax law.

23. The key objectives of this review are:

a) To ensure that the tax rules applying to debt remission are fair and equitable and in accord with the broad base low rate paradigm;

b) To ensure that the tax rules applying to debt remission only taxes net economic income of an “economic group” – that is, where there has been an economic change in net wealth or ownership.

24. Both these objectives rank equally.

REGULATORY IMPACT ANALYSIS

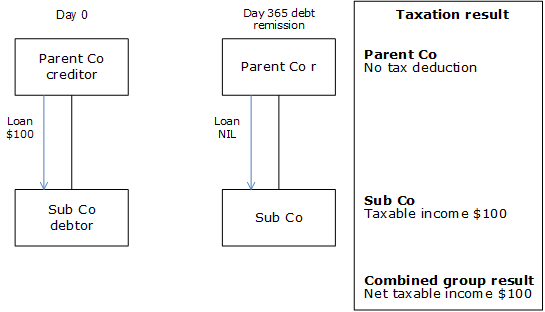

25. The problem is best illustrated:

Example 2

26. There are two options for resolving the problem:

- Option 1: Turn off the debtor’s debt remission income (Sub Co no longer has $100 taxable income in Example 2); or

- Option 2: Allow the creditor a bad debt deduction (Parent Co gets a $100 tax deduction in Example 2).

27. As can readily be seen there are no other options.

28. Turning off the debtor’s debt remission income (Option 1) is the best solution because:

- If the debtor is insolvent (as is often the case) it would likely not be able to pay tax on the debt remission income, whereas Option 2 would allow the creditor a bad debt tax deduction. This situation would result in an asymmetric taxation position (bad debt deduction, but in practice no debt remission income) but this time in favour of the taxpayer.

- If the creditor is not a company (and therefore is not able to group losses) and the debtor is a company owned by the creditor, Option 2 allows the creditor a bad debt deduction which it might not be able to utilise (perhaps because their only income is from imputed dividends from the company), but the debtor would have a real tax liability.

- Option 2 would not offer a symmetric solution as the creditor’s bad debt deduction would be outside the New Zealand tax base – that is, the remission income would be in New Zealand, but not the corresponding Option 2 deduction.

Addressing the issue of cross-border debt

29. As noted in the status quo section of this RIS, there is a question of whether any legislative solution applying to domestic debt should also apply to inbound debt.

30. Interest expense from debt associated with non-resident owners is a key BEPS issue being considered by the OECD. Allowing non-resident owners of New Zealand companies to remit (or capitalise) debt without consequence will likely, at least at the margin, make it easier to deduct interest expense (because it doesn’t have to be paid in cash).

31. New Zealand (and a number of other countries) has thin capitalisation rules that limit the debt to equity ratio in order to restrict profits being inappropriately reduced by interest expenses. This rule, along with the transfer pricing rules, is the primary limitation on excess interest deductions being taken in New Zealand.

32. The OECD BEPS review will lead to further consideration of our thin capitalisation rules. The likely results of this are further amendments that will reduce the risk of allowing the remission or capitalisation of inbound debt.

33. Further, although there are a number of marginal examples of inbound owner’s debt (where the debt to equity ratio exceeds a standard commercial ratio), there are also examples of debt capitalisations where the underlying debt to equity ratio does not cause policy concerns. Devising a debt remission rule to target just the inappropriate debt capitalisations would be difficult and arbitrary.

34. Also, the recent amendments to the thin capitalisation so that they now apply to investors “acting together” have buttressed the thin capitalisation rules, and, at least at the margin, the non-resident withholding tax proposals that are currently being consulted upon will also help in this regard.

35. Acknowledging that the primary method of limiting interest deductions on inbound debt is and should be thin capitalisation, we consider that on balance the debt remission changes should also apply to inbound debt as well as to domestic debt.

Summary of impacts of Option 1

36. Option 2 is not considered as it is ineffective at solving the core problem.

37. There are no fiscal impacts associated with Option 1 because taxpayers are not presently paying tax based on the status quo. Given the policy decision that debt capitalisations should not be taxed, it would be appropriate to back date any legislative amendment so as to provide the private sector certainty. Thus, the Government may forgo a windfall fiscal gain but there would be no actual impact on the fiscal position (note that there is a small fiscal gain from one of the technical changes that will be made as a result of this project).

38. The extension of the preferred solution to inbound debt is not predicted to have fiscal consequences, but this assumes that New Zealand’s thin capitalisation rules will be further considered as a result of the BEPS review.

39. Removal of the present asymmetrical taxation outcome is expected to reduce compliance costs on a go-forward basis over the status quo. This is because it is equitable, simple and certain and taxpayers will not need to structure transactions to get to this end result. Further, the retrospective removal of the suggestion that tax advisers and their clients might have been involved in tax avoidance transactions will be welcome.

40. Option 1 is not expected to have any ongoing administrative implications for Inland Revenue.

41. There are no environmental, cultural or social implications associated with Option 1.

CONSULTATION

42. The usual taxation GTPP (the generic tax policy process) has been followed in full. The consultation has been both formal, by way of the February 2015 Officials’ issues paper Related parties debt remission, and informal. The matter was first drawn to our attention by Chartered Accountants Australia and New Zealand (CAANZ) in late 2013. At about the same time Inland Revenue’s Office of the Chief Tax Council (OCTC) also referred the matter to Inland Revenue’s Policy and Strategy division.

43. Since then there have been many informal discussions with tax lawyers and accountants. These have been both before and after the formal consultation. The initial discussions focused on how important the matter was, and how distortionary the asymmetric effect would be. Later discussions (after the release of the issues paper) have focused on the inbound debt issue and on the detail.

44. The issues paper was released in February 2015 and was very positively received, notwithstanding that it left the question of inbound debt open. Eight submissions were received. CAANZ, the New Zealand Law Society, the Corporate Taxpayer Group, KPMG, Chapman Tripp and EY, as well as two single office accounting firms.

45. Through both the formal and informal consultation there has been a total consensus between officials and the private sector on the high level problem definition and the answer. Once the problem was defined there has been a private sector consensus on how to treat inbound debt, although, at least informally, the risks in this space have also been mentioned and officials’ reservations acknowledged.

46. Two senior accountants have peer reviewed the proposals as they have developed and their views have helped shape the final conclusions.

47. In addition, there have been presentations to the private sector on the policy issues and potential fixes that were very well received – most notably in November 2014 at the CAANZ Tax Conference, but also at the conference of the New Zealand branch of the International Fiscal Association in March 2015.

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

48. Option 1 – turn-off debtor’s remission income is the only effective option because it addresses the present asymmetric debt remission problem in all appropriate situations where there is no change in net economic wealth or ownership.

49. In contrast Option 2 is ineffective at preventing the mismatches between income and expenditure that have the potential to occur.

50. In addition, the preferred option should also apply to inbound debt.

IMPLEMENTATION

51. The proposed changes will be announced by the Ministers of Finance and Revenue following Cabinet approval. At the same time brief informal discussions with the private sector on the detail of the proposals will continue.

52. Legislation to give effect to the proposed changes will be included in the next omnibus taxation bill, which is expected to be referred to the Finance and Expenditure Committee for consideration, which typically involves receiving submissions from the public. Enactment is expected in the second half of 2016.

53. Both the Bill’s commentary (as the Bill is introduced), and Inland Revenue’s Taxation Information Bulletin that follows the enactment of the Bill, will detail the proposals. Furthermore, although it is beyond Inland Revenue’s control, it is very likely that the private sector tax education courses will cover the matter off in some detail.

54. Internally Inland Revenue will adopt its usual practices in informing staff of the amendments.

55. No particular implementation or compliance issues are expected to arise.

56. Once enacted the proposed changes will be administered by Inland Revenue as part of its business as usual.

MONITORING, EVALUATION AND REVIEW

57. The private sector reaction to the proposals will be monitored and evaluated, particularly for inbound debt. This will be through the usual tax return review process, which already has some focus on inbound debt situations.

58. As well tax policy advisors will continue to issues with debt associated with inbound investment with the private sector taxation community. Also, the private sector can be relied upon to bring to official’s attention any problems in applying the amendments.