NRWT: Related party and branch lending – bank and unrelated party lending

AGENCY DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

This Regulatory Impact Statement (RIS) has been prepared by Inland Revenue.

It provides an analysis of options to ensure that approved issuer levy (AIL) is applied consistently on interest payments to non-residents on third party funding or funding that is economically equivalent to third party funding. Specifically, the options are aimed at addressing the current tax advantage enjoyed by foreign-owned banks compared to New Zealand-owned banks and non-bank borrowers that arises from the application of the NRWT rules to onshore and offshore branches of these foreign-owned banks.

Analysis has been undertaken on existing interest payments by registered banks that are not subject to non-resident withholding tax (NRWT) or AIL but would be subject to these taxes if they were not occurring through an offshore or onshore branch. The fiscal estimates are based on current interest rates but the impact of higher interest rates has also been considered. We have assumed that current offshore borrowing levels would continue although we have considered ongoing regulatory changes in New Zealand and other countries that might reduce the amount of funding sourced through these branches.

It is not possible to accurately determine the impact this additional tax would have on interest rates. If the foreign-owned banks using bank branch structures to avoid paying AIL or NRWT are currently passing on the full benefits of this to domestic consumers, repealing this exemption could cause interest rates to rise by one fiftieth (e.g. from 5.0% to 5.1%). However, officials consider that this is likely to be a maximum possible increase. The banks affected by these changes are competing with other banks that are already subject to AIL on interest payments to non-residents. As a result they may be passing on less than the full benefit of their current exemption to domestic borrowers. Because banks raise funds from a variety of sources, including domestic deposits that are not subject to AIL, for interest rates to increase by any amount close to the maximum, deposit rates would also be expected to rise by a similar amount.

The changes will lead to a more neutral and consistent treatment of the existing AIL rules. They will level the playing field between a number of foreign-owned banks that are using branch structures and both New Zealand owned banks which typically pay AIL as well as most other non-bank borrowers where interest paid to non-resident third party lenders is normally subject to either AIL or NRWT.

The changes will not completely level the playing field in two respects. First, neither NRWT or AIL will apply to respect of interest earned by a foreign bank with an onshore branch even where that interest is not earned by the branch. Second interest on certain widely-held bonds is exempt from AIL and NRWT.

The widely held bond exemption is relatively small; less than $2 million of AIL is being forgone as a result of it. On the other hand, $47 million of AIL is being collected. The judgement has been taken that this change will lead to a more neutral overall tax regime by treating borrowing through banks with branch structures in a way which is more consistent with most other forms of borrowing.

A range of options have been considered and measured against the criteria of economic efficiency, fairness and certainty and simplicity. There are no environmental, social or cultural impacts from the recommended changes.

Inland Revenue considers that aside from the constraints described above, there are no other significant constraints, caveats and uncertainties concerning the regulatory analysis undertaken.

None of the policy options identified are expected to restrict market competition, unduly impair private property rights or override fundamental common law principles.

Carmel Peters

Policy Manager

Policy and Strategy

Inland Revenue

1 December 2015

STATUS QUO AND PROBLEM DEFINITION

1. The general treatment of interest payments to non-residents is to apply non-resident withholding tax (NRWT) unless the payment is to an unrelated party in which case a 2% approved issuer levy (AIL) can be paid instead of NRWT. NRWT is normally payable at a rate of 10% if the lender’s home country has a double tax agreement (DTA) with New Zealand, or a rate of 15% in other cases.

2. Further details on the NRWT and AIL rules are set out in the related RIS NRWT: Related party and branch lending – NRWT changes (1 December 2015) (the NRWT RIS).

3. Many non-resident lenders require New Zealand borrowers to gross up their interest payments for NRWT so that the cost of the tax is borne by the borrower rather than the lender. Applying AIL to third party lending helps ensure that taxes on interest do not push up interest rates in New Zealand too much. Paying AIL is a voluntary alternative to NRWT; however, AIL cannot be offset against the lender’s income tax liability in their home country[1].

4. International evidence suggests that taxes on interest paid abroad can be passed on in the form of higher interest rates, and it is common for other countries to have measures to limit such taxes for that reason. The AIL option for third party debt is New Zealand’s way of achieving this outcome.

5. There are currently three structures involving either a New Zealand branch of a non-resident or the offshore branch of a New Zealand resident that can be used so that neither NRWT or AIL is payable on interest payments to non-residents. These structures are inconsistent with the policy intention of applying NRWT or AIL to interest payments to unrelated non-residents.

Offshore branch exemption - issues

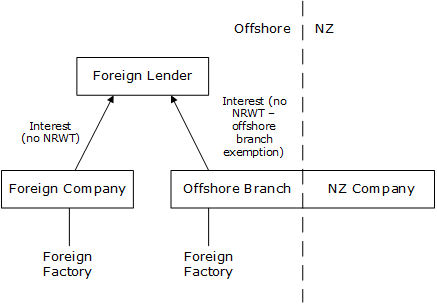

6. If an offshore branch of a New Zealand resident borrows money from a non-resident lender to fund a business they carry on outside New Zealand, the interest on this funding is not subject to NRWT or AIL (we refer to this as the “offshore branch exemption”). This exemption ensures that the tax treatment of foreign branches of New Zealand residents is consistent with that of foreign incorporated subsidiaries of a New Zealand-resident. This is illustrated in figure 1 below.

Figure 1: Offshore branch exemption

7. However, a business carried on outside New Zealand can include the business of borrowing money for the purpose of lending to New Zealand residents. This allows a New Zealand resident (including a bank) to set up a subsidiary with an offshore branch. This branch can borrow, and make interest payments to, a non-resident without incurring NRWT or AIL then lend that money to another New Zealand resident. This is illustrated in Figure 2 below..

Figure 2: Offshore branch exemption for New Zealand borrowing

8. This scenario creates a situation in which interest payments on funding borrowed by an offshore branch of a New Zealand resident, who then on-lends to another New Zealand resident, are not subject to NRWT or AIL. This result arises even though interest payments on an equivalent loan by a non-resident to a New Zealand resident would be subject to NRWT or AIL.

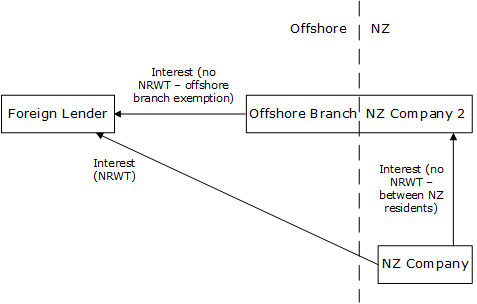

Onshore branch exemption - issues

9. The onshore branch exemption as it applies to borrowing by non-banks is considered in the NRWT RIS. This RIS only considers borrowing by a New Zealand registered bank.

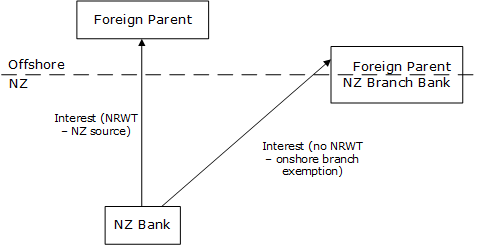

10. As a result of the onshore branch exemption, interest payments by a New Zealand-resident bank to an associated non-resident lender are not subject to NRWT or AIL where the non-resident has a New Zealand branch. This is illustrated in figure 3 below.

Figure 3: Onshore branch exemption

11. This scenario creates a situation where funding borrowed by a New Zealand bank from their non-resident parent is not subject to NRWT or AIL provided the non-resident has a branch in New Zealand. This result arises even though interest payments on an equivalent loan by the non-resident parent without a New Zealand branch would be subject to NRWT or AIL.

Onshore notional loans - issues

12. A non-resident bank can borrow offshore for the purpose of funding its worldwide operations and allocate a portion of this funding to its New Zealand branch. The New Zealand branch can then use the funding to make loans and generate taxable income. When calculating its net income taxable in New Zealand, the bank can deduct from the income generated by its New Zealand activities a deemed interest amount, attributable to the borrowing raised offshore and used to fund the New Zealand business.

13. New Zealand is unable to impose NRWT or AIL on any portion of the interest paid on the offshore borrowing by the bank. Currently, NRWT or AIL are not imposed on the interest which the New Zealand branch is deemed (as described above) to pay to the non-New Zealand part of the bank which provides it with funding.

14. The result is that interest paid on funding allocated to a New Zealand branch is not subject to NRWT or AIL even when interest payments on an equivalent loan by a non-resident to a New Zealand resident subsidiary company would be subject to NRWT or AIL.

Coherence and consistency of the AIL rules

15. These branch structures are available and practical for New Zealand’s larger foreign-owned banks but not for New Zealand’s domestically-owned banks. New Zealand borrowers seeking funding from overseas have the option of borrowing directly or through a New Zealand bank which may or may not be using these branch structures. Generally non-bank New Zealand borrowers are unable to use the onshore or offshore branch structures explained above so their interest payments to non-residents will be subject to NRWT or AIL. Also, borrowing through New Zealand’s domestically-owned banks will be subject to AIL, On the other hand, borrowing from a New Zealand foreign-owned bank that uses these structures will not incur NRWT or AIL.

16. As borrowing in these different ways is highly substitutable, the different forms of borrowing should be subject to the same tax treatment so that tax does not incentivise one behaviour over another. This is not currently the case.

17. In particular, New Zealand banks that are not owned by a foreign bank or do not have sufficient scale to operate an offshore branch cannot make interest payments to non-residents without incurring NRWT or AIL. This creates a tax disadvantage for New Zealand-owned banks when compared to their foreign-owned competitors. Alternatively, if foreign-owned and domestic-owned banks offer equivalent interest rates yet only domestic-owned banks are subject to AIL this may suggest that the tax rules are providing additional profit to foreign-owned banks.

Zero-rated AIL on widely held NZ dollar bonds

18. AIL can be reduced to zero on interest payments on certain widely-held New Zealand dollar bonds. The existence of the bank branch exemptions was a motivating factor behind the introduction of widely-held bond zero rating. Zero rating removed a bias favouring borrowing through banks using branch structures over firms issuing widely held or listed bonds. There was a concern that this bias was impeding the development of a domestic bond market.

19. If the preferred options in this RIS are enacted, AIL would have to be paid on all interest from offshore borrowing through branch structures except interest paid by a non-group member to the head office of a bank with a New Zealand branch. Accordingly, and particularly if this remaining bank branch exemption is ever removed in the future, the zero rating of widely held bonds could, in the longer run, be reviewed. Finally, it is worth noting that this exemption is very much at the margin with less than $2 million of AIL (i.e., AIL on less than $100 million of interest on widely-issued bonds) escaping tax as a result of this zero rating. By comparison $2,350 million of interest is currently subject to AIL and $47 million of revenue is collected from this tax.

Cost of capital

20. Other things being equal, there can be attractions in ensuring tax rules do not push up interest rates too much as this can raise the cost of capital, i.e. the hurdle rate of return that firms require to undertake investment. This, in turn, can lead to firms not undertaking certain investments that are attractive at world prices. However, a 2% rate of AIL is an extremely low rate of tax on interest paid abroad and officials see this tiny impost as an acceptable part of the AIL/NRWT mechanism that New Zealand has chosen to adopt. Officials do not see that cost of capital arguments provide good grounds for allowing an exemption from AIL for foreign-owned banks when this is not more generally available.

21. Although it was not a policy decision to exempt banks from AIL it is possible that the cost of capital is lower as a result of the exemption as banks will have lower net of tax funding costs and this may be reflected in lower interest rates for New Zealand borrowers.

22. Prior to and during the 1990s New Zealand banks, including foreign-owned banks were liable for NRWT or AIL on interest payments as they were not borrowing exclusively through branches. More recently New Zealand-owned banks have continued to be liable for AIL as they cannot access the branch exemptions. These New Zealand-owned banks are competing with the foreign-owned banks so it is not clear that foreign-owned banks will currently be passing on all of the benefits of not paying AIL to domestic borrowers. In this case the foreign-owned banks may not be able to pass all of their additional AIL liability to domestic borrowers in higher interest rates. Instead it may cause a minor reduction in those banks’ after-tax profits.

23. It is not possible to determine which of these two scenarios will arise, in part because AIL will be such a small proportion of a bank’s total funding cost[2]. To be conservative this RIS proceeds on the basis that the imposition of AIL to foreign-owned banks would result in a very small increase in the cost of capital as a result of higher interest rates being charged by the foreign-owned banks that are currently using branch structures.

24. If the costs were being fully passed on, including being reflected in higher deposit rates, making AIL payable would be expected to increase interest rates by a factor of one fiftieth (e.g. from, say 5.0% to 5.1%). But this is a maximum assumption.

25. To put the size of a 0.1% increase in context this is less than half the minimum change of 0.25% that the Reserve Bank can make to the official cash rate at its regular reviews. Officials have consulted with the Reserve Bank over these changes and they have raised no concerns.

OBJECTIVES

26. A principal of our broad-based low-rate (BBLR) tax framework is that tax should not incentivise one form of investment over another economically equivalent investment. The current application of the NRWT rules to onshore and offshore branches creates a tax advantage towards foreign-owned banks against New Zealand-owned banks and non-bank borrowers.

27. The main objective of this reform is to reduce or remove this bias and thereby improve the integrity of the NRWT and AIL rules while minimising the effect of the rules on the cost of capital for unrelated party borrowers.

28. The criteria against which the options will be assessed are:

- Economic efficiency: The tax system should, to the extent possible, apply neutrally and consistently to economically equivalent transactions. This means the tax system should not provide a tax preferred treatment for one transaction over another similar transaction or provide an advantage to one business over another. This helps ensure that the most efficient forms of investment which provide the best returns to New Zealand as a whole are undertaken. At the same time there is a concern that taxes should not unduly raise the cost of capital and discourage inbound investment.

- Fairness: Taxes should not be arbitrary and should be fair to different businesses. Neutrality and consistency across economically equivalent transactions is likely to also promote fairness.

- Certainty and simplicity: The AIL rules should be as clear and simple as possible so that taxpayers who attempt to comply with the rules are able to do so.

29. While all criteria are not equally weighted they are all important. Any change (except for the status quo) would have to improve neutrality and consistency of treatment. This would tend to promote economic efficiency and fairness. At the same time, the measures would also tend to increase the cost of capital in some circumstances so there are trade-offs to consider. Due to the complexity of these transactions, the sophistication of taxpayers who would be subject to the proposed changes, and that AIL only applies on a payments basis, certainty and simplicity is the least important criterion.

REGULATORY IMPACT ANALYSIS

30. As the onshore and offshore exemptions currently rely on separate rules it is anticipated that separate options would be required to achieve the main objective. The preferred options could be implemented collectively or individually but implementing a single option may not achieve the objective.

31. The range of available options are:

- Option 1: Status quo

- Option 2: Remove or zero-rate AIL on unrelated party borrowing

- Option 3: Introduce a widely offered test to zero-rate AIL

- Option 4: Introduce a specific bank exemption from AIL

- Option 5: Apply AIL to interest payments made by offshore branches to the extent that they lend to New Zealand (preferred option)

- Option 6: Apply AIL to interest payments made to a non-resident that has a New Zealand branch with a banking licence if the lender and borrower are associated (preferred option)

- Option 7: Apply AIL to notional loans to a New Zealand branch (preferred option)

- Option 8: Defer AIL changes until a review of widely-held exemptions is undertaken

32. If options 5 to 7 are introduced officials considered one additional option:

- Option 9: Allow AIL on related party interest payments by banks (preferred option)

33. Officials consider that options 5 to 7 and 9 should be considered as a package as implementing one or two of options 5 to 7 without the third would leave a source of funding by non-residents that was not liable for NRWT or AIL on interest payments and therefore would not achieve the objective.

34. Further detail on each option is provided in the paragraphs below. An assessment of each option against the range of impacts is also included.

35. There are no social, cultural or environmental impacts for any of the options considered.

Option 1: Status quo

36. The status quo is that the New Zealand operations of most foreign-owned banks do not pay AIL on interest payments that are ultimately to unrelated non-residents whereas most New Zealand-owned banks and non-banks (because they cannot practically operate commercial onshore or offshore branches) are required to pay AIL when they make interest payments to unrelated non-residents.

37. Foreign-owned banks would continue to be not subject to AIL on interest payments to non-residents so there would be no impact on the cost of capital.

Assessment against criteria – option 1

38. The current legislation does not provide specific bank exemptions from AIL; however, due at least in part to non-tax reasons they operate structures that can achieve this effect. While this has been the case in some instances for over 20 years, this was not a deliberate policy choice and there are no convincing policy arguments why some banks should not be required to pay AIL when other banks and sectors of the economy are required to do so. The current rules provide a competitive advantage to one group of lenders. Therefore, this option does not meet the economic efficiency or fairness criteria.

39. Because there would be no changes to the existing rules, which are widely understood, this would meet the certainty and simplicity criterion.

Option 2: Remove or zero-rate AIL on unrelated party borrowing

40. Because a large portion of interest payments by New Zealand residents to unrelated non-residents are by banks that do not currently pay AIL this option would align with this treatment if all interest payments to unrelated non-residents were not subject to AIL. This treatment could be achieved by either removing AIL completely or reducing the rate from 2% to zero; either of these approaches would have the same practical effect. For the purpose of the remainder of this RIS this is referred to as “zero-rating AIL”. This treatment would also be consistent with the zero-rated AIL provisions for widely-held NZ dollar bonds referred to above.

41. The rationale for giving borrowers the choice between AIL (at a rate above 0%) and NRWT is that it allows New Zealand to continue to collect NRWT on interest paid to foreign lenders who are indifferent about paying New Zealand tax, while minimising (though not eliminating) the deadweight cost[3] to the economy arising from taxing other foreign lenders.

42. This rationale would no longer apply if AIL were zero-rated as foreign lenders would no longer have an incentive to have NRWT withheld. Therefore, as well as reducing AIL collected by approximately $47 million per annum this would also reduce NRWT payments by at least $42 million per annum for a total of at least $89 million per annum. These NRWT payments are unlikely to increase borrowing costs and impose negligible costs on New Zealanders. They are likely to be much less costly to New Zealand than replacement taxes would be.

43. Although the reduction in taxes on interest payments to non-residents would lower the cost of capital this would have to be balanced against the reduction in tax revenue which would be much larger than the effect on domestic interest rates due to the reduction in NRWT that has no impact on the cost of capital.

Assessment against criteria – option 2

44. This option does not meet the economic efficiency criterion as it would forgo NRWT payments that do not increase the cost of capital which are likely to be much less costly to New Zealand than replacement taxes would be.

45. This option does meet the fairness criterion as all interest payments to unrelated non-residents and by New Zealand banks would not be subject to AIL (or NRWT). For the same reason it would also meet the certainty and simplicity criterion.

Option 3: Introduce a widely offered test to zero-rate AIL

46. Some countries (for example Australia) allow withholding taxes to be zero-rated if the borrowing is widely offered. This option would essentially be an extension of the existing widely held zero-rated bonds provisions enacted in 2012, so they applied in a much wider range of circumstances.

47. The existing widely held zero-rated bonds provisions allow AIL to be zero-rated only when specific criteria are met. These include that the security is denominated in New Zealand dollars, the issue of the security was a regulated offer under the Financial Markets Conduct Act 2013, and the activities of the registrar and paying agent for the security are carried on through a fixed establishment in New Zealand. While New Zealand banks are not prevented from issuing debt that complies with these requirements, most existing issues will not do so.

48. Officials do not see that the imposition of AIL on widely offered debt would have an impact on the cost of capital that would be significantly different to other international funding sources such as non-widely offered wholesale bonds or private placements. Implementing a widely offered test would impose higher compliance and administration costs to ensure that the required criteria were met and it would be difficult to justify this boundary.

49. Officials expect that support for this option comes from borrowers who would be able to meet a widely offered test rather than there being strong policy reasons for this distinction.

50. This option would codify the existing lack of AIL on most interest payments by foreign-owned banks and remove AIL from a number of New Zealand-owned bank and non-bank borrowers which would reduce tax revenue. However, compliance and administration costs would increase significantly compared to the current rules or other options in this RIS.

Assessment against criteria – option 3

51. This option would not meet the economic efficiency and fairness criteria. Although this option would shift the boundary between what interest payments were liable for AIL it would make no effort to remove, or even explain, this arbitrary boundary. Interest payments on widely held bonds would be exempt from AIL whereas an otherwise equivalent interest payment to a single lender would not. Similar arguments regarding a boundary between widely held and closely held debt were made by submitters in relation to the AIL registration proposals considered in the NRWT RIS.

52. The widely offered test could be drafted so that it provided sufficient certainty in its intended application but this would require regular monitoring by issuers to ensure new and ongoing issues continued to be compliant with the tests. Therefore, this option would only partially meet the certainty and simplicity criterion.

Option 4: Introduce a specific bank exemption from AIL

53. Currently, most interest payments to non-residents on borrowing by banks are not subject to AIL. However, there are no bank specific rules to achieve this. The tax system could be made more coherent and transparent if a specific exemption were introduced that interest payments by banks should not be subject to AIL (or NRWT). This could be limited to wholesale interest or to all payments. Either option would make no attempt to reconcile why interest paid by banks to non-residents should not be subject to AIL when all other industries were required to pay AIL on their interest payments.

54. Introducing a wholesale bank funding exemption would largely codify the existing outcome with an extension to New Zealand-owned banks and any other bank funding that was not or could not access the branch exemptions. This exemption would require a robust definition of wholesale funding to be developed. Officials estimate the revenue cost of this option would be approximately $1 million per annum.

55. Introducing an exemption for all interest payments by banks would involve forgoing the NRWT and AIL payments currently made by banks which are predominantly on retail deposits. The estimated revenue cost of this option is approximately $62 million per annum. NRWT withheld on retail deposits would almost always be creditable so would normally not be expected to increase interest rates. It is a very efficient form of tax from a New Zealand perspective and it would therefore be undesirable to eliminate it.

56. The argument for a bank exemption is that the imposition of AIL would increase the interest rate charged and therefore the cost of borrowing for New Zealand borrowers. As explained in option 5 and 6 below, we do not consider this would have a material impact on the cost of borrowing and consider it to be an acceptable part of New Zealand’s AIL/NRWT mechanism.

57. If it were accepted New Zealand would be better off if banks did not pay AIL due to the effect on the cost of capital, this would also apply to any other industry that borrowed from unrelated non-residents in order to supply New Zealand residents. For this reason, officials do not support either a general exemption from AIL for banks or an exemption limited to wholesale funding.

58. Therefore, officials consider it would be difficult, if not impossible, to justify an exemption for banks without it being extended to cover other industries. This extension would make this option almost the same as option 2 which, as noted above, officials do not prefer.

59. Introducing a wholesale bank exemption would reduce the funding costs of New Zealand-owned banks which could in turn reduce the cost of capital (but, only if these banks passed this reduction through in their lending rates). Introducing a wider banking exemption would also reduce the cost of capital but the effect on government revenue would be much larger which may flow through into cost of capital increases elsewhere in the economy.

Assessment against criteria – option 4

60. This option would partially meet the economic efficiency and fairness criteria. Although it would add additional neutrality to the banking sector it would not address neutrality between banks and non-banks.

61. A wide banking exemption would be simple to apply whereas a wholesale bank exemption, depending on how it was drafted, could have some boundary issues over exactly what is wholesale funding. On balance, this option would meet the certainty and simplicity criterion.

Option 5: Apply AIL to interest payments made by offshore branches to the extent that they lend to New Zealand (preferred option)

62. The offshore branch exemption, as shown in figure 2 above, results in an interest payment to a non-resident by an offshore branch of a New Zealand resident not having a New Zealand source and therefore not being subject to AIL. The offshore branch exemption was not designed to exempt New Zealand banks from AIL or NRWT (as demonstrated by the fact that the rule existed several decades before its widespread application by the banking industry) and was instead intended to apply a similar tax treatment to interest payments by an offshore branch of a New Zealand resident as that which applies to interest payments by an offshore subsidiary of a New Zealand resident.

63. This option would limit the offshore branch exemption so that an interest payment by an offshore branch of a New Zealand resident to a non-resident would have a New Zealand source if that branch used the money to lend to a New Zealand resident. The offshore branch exemption would be retained if the branch used that money for its foreign operations, that didn’t include lending to New Zealand, for example, to build an offshore factory.

64. In practice, this option is unlikely to result in any apportionment issues as we have not observed any offshore branches which borrow for the purpose of lending to New Zealand residents and operating an offshore business that does something other than lending to New Zealand residents. If, in the future, this were the case we expect interest costs could be apportioned on a reasonable basis

65. The consequence of this change would be that an interest payment by the offshore branch would be subject to AIL but the interest payment by the New Zealand borrower to the offshore branch would continue to be an interest payment between two New Zealand residents. This would result in the same amount of AIL paid as if the New Zealand borrower made the interest payment directly to the non-resident without interposing the offshore branch.

66. Officials recognise that there are commercial reasons why a New Zealand bank might wish to establish an offshore branch including, for example, to maintain face-to-face relationships with lenders or to be in a similar time zone. This option would not require a bank to close such an offshore branch. Banks would be free to continue to obtain the commercial benefits currently achieved. However, the cost of operating the branch would no longer be subsidised by a tax saving.

67. Additional costs imposed on banks currently accessing this exemption are not material compared to existing bank funding costs[4] or taxes already applied to the banking sector. While this may have some effect on the cost of capital we consider this to be very minor.

Assessment against criteria – option 5

68. This option meets the economic efficiency and fairness criteria as offshore branches would no longer be able to be used to remove NRWT or AIL from interest payments to non-residents.

69. Offshore branches are already aware of the amount of interest payments they make to non-resident lenders. While there are peripheral issues that add complications this option would meet the certainty and simplicity criterion.

Option 6: Apply AIL to interest payments made to a non-resident that has a New Zealand branch with a banking licence if the lender and borrower are associated (preferred option)

70. In the NRWT RIS we recommended restricting the onshore branch exemption so it only applied when an interest payment was made to a non-resident with a New Zealand branch if the interest payment was made to the New Zealand branch or the New Zealand branch had a banking licence.

71. This option considers a further restriction on that exemption so that it would not apply when a New Zealand resident makes an interest payment to an associated non-resident that has a New Zealand branch with a banking licence. The primary application of this restriction would be to apply AIL to interest payments by a foreign-owned New Zealand bank to their offshore parent bank.

72. This structure appears to be used less than the other two branch structures considered in this RIS and so this option would also have a correspondingly lower impact on revenue raised. However, in the absence of this change, and if the other preferred options were enacted, additional funding could be transferred into this structure. The additional costs imposed on banks currently accessing this exemption would not be material compared to existing bank funding costs or taxes already applied to the banking sector. Although this option might have some effect on the cost of capital we consider this to be very minor.

Assessment against criteria – option 6

73. This option would meet the economic efficiency and fairness criteria as the onshore branch exemption would no longer be able to be used to remove NRWT or AIL from interest payments to non-residents in a way that would not be available to non-banks.

74. Foreign-owned banks would already be aware of interest paid to their non-resident associated parties and so AIL could easily be applied to these payments. This option would meet the certainty and simplicity criterion.

Option 7: Apply AIL to notional loans to a New Zealand branch (preferred option)

75. To the extent that a head office borrows for general purposes, and then uses the funds raised in part to fund its New Zealand branch, the interest paid by the head office on the general purpose borrowings cannot practically be subject to New Zealand NRWT or AIL. This is because it is not possible to identify which funding was used for the New Zealand branch. However, it is relevant that in calculating its New Zealand taxable income, the branch is entitled to a deduction for the deemed interest paid on the deemed loan from head office.

76. Deeming recognises that as a legal matter it is not possible for one part of a single entity to lend money to another. The deeming is a way of allocating to the New Zealand branch a portion of the entity’s worldwide borrowing and interest cost.

77. The notional interest proposal involves imposing AIL at 2% on this deemed interest. Australia has a similar provision, which imposes NRWT on 50% of the deemed interest deducted by the Australian branch of a non-Australian bank. (In practice, this means a withholding tax rate of 5%).

78. This option puts a New Zealand branch of a non-resident bank in the same tax position as a New Zealand subsidiary. In the latter case, any loan funding from the parent is an actual, not a notional, loan, and NRWT (or, under our proposals, AIL) already applies to the interest on that loan.

79. The fiscal estimates of this option are identical to those for option 5. This is coincidental and arises from lower principal amounts through the onshore branch but at higher New Zealand dollar interest rates compared to lending via the offshore branch which are in lower interest rates for currencies such as British Pounds and Euros. This foreign dollar lending is then swapped back into New Zealand dollars which generates a similar overall cost to New Zealand dollar lending. However, these swap costs are not subject to NRWT or AIL.

80. The additional costs imposed on banks currently using this funding source are not material compared to existing bank funding costs or taxes already applied to the banking sector. Although this might have some effect on the cost of capital we consider this to be very minor.

Assessment against criteria – option 7

81. This option would meet the economic efficiency and fairness criteria as funding allocated to a New Zealand branch would become subject to AIL. This treatment would be consistent with their existing income tax deductions and the income tax and AIL treatment of other forms of funding from non-residents including New Zealand branches that have specific funding allocated to them by their head office.

82. New Zealand branches are already calculating a cost allocation for interest costs on funding allocated by their head office for the purposes of claiming an income tax deduction an so AIL could easily be applied to this amount. Therefore, this option would meet the certainty and simplicity criterion.

Option 8: Defer AIL changes until a review of widely-issued exemptions is undertaken

83. There is an argument that the continued existence of zero-rated AIL on widely-held New Zealand Dollar bonds is inconsistent with applying AIL to all other interest payments to unrelated non-residents or non-resident banks. One way to deal with this is to defer making any changes to the three branch structures referred to above until decisions are made on the continued existence of the zero-rated AIL provisions. These decisions would not be made in time for the bill scheduled for introduction in early 2016 and so would result in a delay of at least a year and possibly much longer.

84. Officials do not believe a delay is justified or necessary.

- The zero-rated AIL provisions are currently used by a small number of New Zealand borrowers. In 2013 less than $100 million of interest was zero-rated, meaning that less than $2 million of AIL was foregone. The amount of zero-rated interest has materially declined in each of the two subsequent years. This compares to interest payments (including notional interest) by banks that is not currently subject to AIL of approximately $1,700 million and interest that is already subject to AIL of approximately $2,350 million.

- Due to this difference in relative size between interest on zero-rated bonds and interest paid by banks to non-residents, officials consider that the favourable tax treatment currently applied to the branch structures used by banks has a much larger effect on the neutrality of the tax system than the existing zero-rated AIL provisions.

- The zero-rated AIL provisions were a deliberate policy choice to encourage the development of a New Zealand bond market, whereas the rules applied to banks were an unintended outcome of policy decisions made in the 1960s for other reasons that do not have similar externalities.

- For compliance and administrative reasons, we have not applied AIL or NRWT on interest paid by a non-group member to the head office of a bank with a New Zealand branch. This decision would also need to be reviewed if we were to review the zero rating of widely held bonds.

85. Also, as the NRWT RIS recommends changes to the onshore branch exemption for non-banks and this option involves considering further changes to the onshore branch exemption for banks but in a later period this would result in having to amend the same provisions in the Income Tax Act 2007 twice, and depending on the degree of deferral even potentially introducing amending legislation before the first amending legislation had been enacted. This is less efficient than implementing the changes as part of a single package. As the zero-rated New Zealand dollar bond provisions are entirely separate no similar concerns arise with analysing this as a separate project.

86. Implementing the preferred options after a deferral would eventually raise additional tax revenue but this would necessarily start in a later period than implementing the same changes as part of the current project.

Assessment against criteria – option 8

87. For any period where decisions on bank branches have been deferred, or if there was ultimately a decision to permanently defer a decision the application to the criteria would be identical to the status quo i.e. it would not meet the economic efficiency or fairness criteria but would meet the certainty and simplicity criterion.

88. If, following a deferral, the preferred options above were implemented, either with or without changes to the zero-rated AIL provisions, when compared against implementing these options as part of the current project this would partially meet the economic efficiency and fairness criteria as neutrality would eventually be achieved but only following a delay which makes this less desirable than meeting these criteria sooner.

89. As officials have already consulted on these proposals and have recommended that a number of changes be introduced as a result of this project it would not add to certainty if certain parts of these changes were deferred in order to be reconsidered at a later date. Also, due to the potential need to re-amend amending onshore branch provisions as noted in the paragraph above there would be less certainty and simplicity than progressing the preferred options as part of the current project. Therefore, the certainty and simplicity criterion would not be met.

Option 9: Allow AIL on related party interest payments by banks (preferred option)

90. Currently, many banks access a portion of their funding by borrowing from a non-resident associated party lender such as their foreign parent bank. This can occur for a variety of non-tax reasons such as it being more efficient for the foreign parent to borrow a large amount then distribute it to its subsidiaries or where the foreign parent’s larger balance sheet and/or higher credit rating allow it to access borrowing or access cheaper borrowing than the New Zealand operations can achieve independently.

91. Officials recognise that related party lending by a bank is unlikely to be a substitute for equity funding and can be distinguished from borrowing by other sectors. As the foreign parent will be entitled to a deduction for their funding costs with likely only a small mark-up on the interest received from their New Zealand operations it is recognised that applying NRWT to the gross interest would be inappropriate.

92. If options 5 to 7 are enacted banks would be required, to the extent they are not already, to pay AIL or NRWT. A consequence of these changes, if implemented by themselves, is it would become uneconomic for a foreign parent to borrow to on-lend to their New Zealand operations and the New Zealand operations would instead attempt to borrow directly even when – in the absence of tax – it may not be economically efficient to do so. To remove this tax disincentive this option would allow a member of a New Zealand banking group (which is already defined for the purpose of the banking thin capitalisation rules) to pay AIL on all interest payments to non-residents even if that non-resident was associated.

93. If options 5 to 7 are not enacted, or option 8 is chosen to defer enactment, we do not recommend this option. The reason for this is the widespread use of the branch exemptions means that foreign-owned banks are not currently paying NRWT or AIL on their related party lending and New Zealand-owned banks do not have related party lending from non-residents. Therefore this option, in the absence of the other AIL changes, would introduce additional legislation that would have no practical effect.

94. In the absence of this option borrowing through a related party – even where in the absence of tax it would be efficient to do so – would incur additional taxes compared to borrowing directly. Therefore, we expect if this option were not implemented foreign-owned banks would source practically all of their funding directly to prevent having to pay NRWT instead of AIL. Therefore, this option is not expected to have any fiscal cost.

Assessment against criteria – option 9

95. This option would meet the economic efficiency and fairness criteria as it would remove the tax disadvantage that would arise from a foreign parent borrowing to on-lend to their New Zealand operations when it was economically efficient in the absence of tax to do so.

96. The payment of AIL on interest payments to associated non-residents by a bank is no more complex than withholding NRWT and removes the incentive to structure around NRWT by borrowing directly so certainty and simplicity would be met.

97. A sub-option would be to extend this treatment to other margin lenders such as finance companies. Officials do not support this option as a bank is an easily definable entity and it is much more difficult to create a broad definition that covers non-bank margin lenders that are predominately funded by third party borrowing of a foreign parent while excluding entities that might be funded by the foreign parent’s equity. Furthermore, there are only a relatively small number of non-bank lenders in this situation and they are generally not able to access the branch structures that would be removed by the preferred options in this RIS. Therefore, the overall effect on these lenders would be to maintain the status quo.

Summary of impact analysis

| Option | Main objective and criteria | Benefits | Costs/risks |

| Option 1 – status quo |

|

|

|

| Option 2 – remove of zero-rate AIL on unrelated party borrowing |

|

|

|

| Option 3 – introduce a widely offered test to zero-rate AIL |

|

|

|

| Option 4 – introduce a specific bank exemption from AIL |

|

|

|

| Option 5 – apply AIL to interest payments made by offshore branches to the extent that they lend to New Zealand (preferred option) |

|

|

|

| Option 6 – apply AIL to interest payments made to a non-resident that has a New Zealand branch with a banking licence if the lender and borrower are associated (preferred option) |

|

|

|

| Option 7 – apply AIL to notional loans to a New Zealand branch (preferred option) |

|

|

|

| Option 8 – AIL defer AIL changes until a review of widely-held exemptions is undertaken |

|

|

|

| Option 9 – allow AIL on related party interest payments by banks (preferred option) |

|

|

|

Key:

Criterion (a) – economic efficiency, criterion (b) – fairness, criterion (c) –certainty and simplicity.

98. The increase in compliance costs from options 5, 6 and 7 are expected to be small. These changes will only affect a small number of taxpayers, mostly banks. AIL will be required to be paid on amounts that are already calculated for either accounting or income tax purposes.

99. Options 2 and 4 would be expected to reduce compliance costs as either banks or all unrelated parties would no longer be required to determine whether AIL was payable. Compliance costs for option 3 would increase as any taxpayer relying on a widely-held or widely-offered criterion would be required to undertake ongoing monitoring to ensure that their new and continuing funding met the necessary requirements.

100. The administration costs of options 2 to 7 and 9 would be small as affected taxpayers would file AIL returns under existing systems. The administration costs of option 8 would be higher as it would result in the duplication of policy analysis and parliamentary process that has already been undertaken. It would also require provisions that are recommended to be amended in the NRWT RIS to be further amended following the deferral period.

101. The fiscal estimate of options 5 and 7 are both $12 million per annum. That these numbers are the same is coincidental as a larger amount of borrowing is currently through structures covered by option 5; however this is at lower currency interest rates such as British Pounds, US dollars and Euros. Once this funding is converted back into New Zealand Dollars the total cost is similar to the New Zealand Dollar and Australian Dollar borrowing through the branch structures covered by option 7; however, this foreign exchange cost is not, and will not be, subject to NRWT or AIL. This $12 million estimate is calculated as a $17 million increase in AIL which will reduce taxable income by the same amount and therefore reduce income tax by $5 million.

102. The fiscal estimate of option 6 has not been separately calculated as we are not aware that there is currently a significant portion of bank funding using this structure. However, if options 5 and 7 were introduced without option 6 it is likely this funding source would increase.

103. The fiscal estimates of options 2, 3 and 4, which are not preferred options, are all negative by between $1 million and at least $87 million per annum depending on which option is chosen.

CONSULTATION

104. Consultation was undertaken on option 5, 6 and 9 as part of the NRWT: related party and branch lending issues paper released in May 2015. 22 submissions were received on the issues paper of which 11 commented on some aspect of these options.

105. Targeted consultation was also undertaken in October 2015 with the New Zealand Bankers’ Association (NZBA) and other non-NZBA member banks in relation to option 7.

106. Submissions on option 9 supported this proposal although some considered it should be extended to non-banks. Officials do not support this extension as covered in paragraph 97 above.

107. Submitters on options 5 and 6 in most cases disagreed with the proposals. The primary concerns were that these changes would increase the cost of capital and would be inconsistent with international treatment of interest payments to unrelated parties.

108. With respect to the cost of capital submissions, the first point to note is that many taxes, including the usual company tax, increase the cost of capital. This does not mean that they should all be eliminated. Taxes are necessary to raise the revenue Government needs to finance its spending. What is important is to minimise economic efficiency costs. In order to do that it is important that taxes are applied as consistently and coherently as possible. That is the objective of the proposal.

109. In our view any impact of this proposal on borrowing costs will in any event be minimal. The effects on borrowing costs will depend on the extent to which New Zealand’s large foreign-owned banks are passing on the benefits of not paying AIL to domestic borrowers. If the benefits were being fully passed on, including being reflected in higher deposit rates, making AIL payable would be expected to increase interest rates by a factor of one fiftieth (e.g. from, say 5.0% to 5.1%). But this is a maximum assumption. Banks that are not subject to AIL are competing with other lending including lending by New Zealand owned banks. As a result they may be passing on little of the benefits of not paying AIL to domestic customers. In this case, the interest rates they charge are likely to rise by a smaller amount. At the same time the change would be removing the commercial advantage that these large foreign-owned banks have over other lenders.

110. With respect to the submission that the current treatment achieves a similar purpose to NRWT exemptions in other jurisdictions, and if removed should be replaced by an exemption such as those seen in comparable jurisdictions, in our view there is much less justification for such exemptions in New Zealand.

111. Other jurisdictions do not have AIL, and are therefore faced with a choice of 10% or 0%. This is the position in Australia. Although they have 0% for particular situations in domestic law, the relevant exemption for interest paid to banks is only given in a few of their recent treaties – so it does not apply across the board (unlike AIL).

112. Because AIL is only 2%, the deadweight costs it imposes are much less than those imposed by a 10% tax.

113. Imposition of AIL ensures that New Zealand does not give up the opportunity to collect NRWT from lenders who are prepared to pay it without passing the cost on to the New Zealand borrower. For example, if we were to exempt all interest paid by New Zealand banks, we would give up approximately $42 million pa of NRWT which is most likely having no effect on borrowing costs, as well as approximately $20 million pa of AIL.

114. Jurisdictions with wide ranging financial sector-related NRWT exemptions (eg the US, the UK) generally have these because they have global financial sectors, and need to provide exemptions to preserve them. New Zealand does not have a global financial sector, and therefore would reap less benefit from providing an exemption.

115. Experience over the last 25 years demonstrates that the imposition of AIL has not prevented New Zealand borrowers, including some banks, from borrowing from offshore lenders at attractive interest rates.

116. Furthermore, there does not seem to be a great deal of international consensus about what the best basis for an exemption might be. Accordingly, we believe the current AIL/NRWT system serves New Zealand well.

117. While officials have taken submissions into consideration, there are relatively limited choices regarding the implementation of options 5 to 7 so the preferred options continue to be broadly consistent with those originally proposed.

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

118. We recommend that options 5 to 7 and 9 are introduced. These changes will ensure that AIL is applied consistently across almost all interest payments to unrelated non-residents. As well as raising additional tax revenue they will increase the coherence of the tax system and are not expected to have a significant impact on the cost of capital.

IMPLEMENTATION

119. Changes to the AIL rules would require amendments to the Income Tax Act 2007, Tax Administration Act 1994 and to any consequential provisions in other legislation. These amendments would be included in a tax amendment bill, planned for introduction in March 2016. We recommend that the preferred options should apply to all new arrangements entered into after the enactment of the legislation.

120. Officials recognise that both borrowing and lending by banks is frequently at interest rates that are fixed for many years and that profit margins are set based on the expectation that both sides of these transactions will be maintained or that break costs will be paid when such arrangements are terminated early.

121. Whether the banks have raised funding from a third party or a related party we recognise that these arrangements cannot be restructured without incurring transaction costs that would limit the profitability of the overall arrangement.

122. In relation to funding raised by an offshore branch this will usually be for terms of up to five years. This also aligns with the terms of many retail mortgage fixed rates. To minimise the effect of these tax changes we recommend that for arrangements entered into prior to the enactment of the legislation the new rules should only apply to interest payments after the start of the sixth year following enactment of the legislation. This will allow most, if not all, existing arrangements to not be subject to the new rules.

123. In relation to funding raised by an associated party from a non-resident with a New Zealand branch bank we recommend that the new rules apply from the date of enactment. This is because these arrangements are used to provide related party funding that has often been structured in this manner specifically to circumvent the NRWT rules.

124. In relation to deemed interest payments on funding allocated to a New Zealand branch we recommend that the new rules apply to interest deductions on existing arrangements from the start of the third year following enactment of the legislation containing these proposals and from enactment date for new arrangements. This delayed application date for existing arrangements recognises that there is, by definition, no specific funding allocated to finance the funding allocated to the New Zealand branch however a period of more than two years following the enactment of the legislation will allow the majority of funding of the head office to have been rolled over in the intervening period.

125. Implementing these changes would require updating a small range of communication and education products.

126. The new rules will be communicated to taxpayers by way of Inland Revenue’s publication Tax Information Bulletin after the legislation giving effect to the new rules has been enacted.

127. The new rules will be administered by Inland Revenue as part of its business as usual processes.

MONITORING, EVALUATION AND REVIEW

128. In general, Inland Revenue monitoring, evaluation and review of tax changes would take place under the generic tax policy process (GTPP). The GTPP is a multi-stage policy process that has been used to design tax policy (and subsequently social policy administered by Inland Revenue) in New Zealand since 1995.

129. The final step in the process is the implementation and review stage, which involves post-implementation review of legislation and the identification of remedial issues. Opportunities for external consultation are built into this stage. In practice, any changes identified as necessary following enactment would be added to the tax policy work programme, and proposals would go through the GTPP.

[1] This is mainly because AIL is paid by the borrower not the lender and, unlike NRWT, AIL is not an income tax.

[2] For example for the 2014 year the general disclosure statements for the five largest banks show total interest expense of $11,515 million.

[3] These costs arise from the increased taxes increasing the cost of capital which decreases the amount of investment and therefore economic activity in New Zealand.

[4] As noted above the 2014 total interest expense for the five largest banks was $11,515 million.