Chapter 5 - Deduction limitation rule

Introduction

5.1 The income earned and the expenditure incurred by a LTC are allocated for tax purposes to the shareholders on the basis of their respective ownership. The ability of each owner to use their share of the LTC’s expenditure deductions against their other income is determined by the deduction limitation rule. The rule was originally developed for limited partnerships, which generally are likely to be more sophisticated entities.

5.2 The deduction limitation rule is intended to ensure each owner cannot deduct tax expenses in excess of what they have invested in the business, which is referred to as their “owner’s basis”. Excess deductions can be a concern from both a revenue protection and economic efficiency perspective. Deductions in excess of the owner’s basis are required to be carried forward for offsetting against future income subject to having adequate “owner’s basis” at that point.

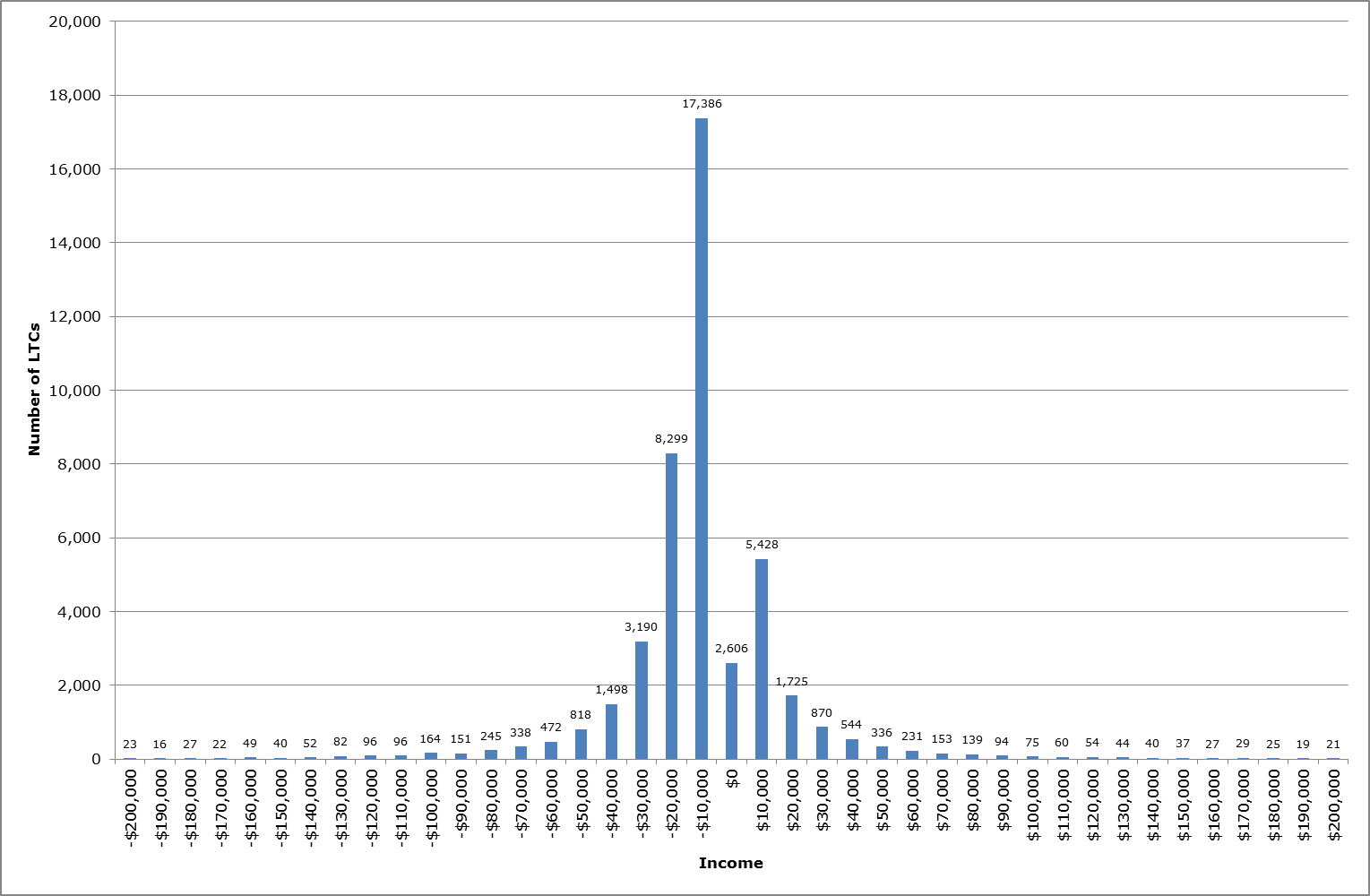

5.3 The deduction limitation rule applies to all LTCs, with all having to undertake the calculations even though in practice it only limits deductions in around one percent of cases. Consequently, the rule is one of the most heavily criticised features of the LTC rules, being criticised from a compliance cost as well as a technical perspective. The fact that the rule has such limited application is in part because, as Chart 1 illustrates, most LTCs fall into the -$20,000 to +$10,000 annual income range.

Chart 1: LTC income – 2013 tax year

The current rule

5.4 At its very basic the owner’s basis is the net funds provided by the shareholder, that is, share capital plus loans to the LTC (whether by way of actual funds or a guarantee by the investor or another party) minus disbursements to the shareholder. This rule is set out in section HB 11 of the Income Tax Act, using the following formula:

investments – distributions + income – deductions – disallowed amounts

where:

investments is the sum of the equity, goods or assets introduced or services provided to the LTC, or any amounts paid by the owner on behalf of the LTC. This includes any loans, including shareholder current account credit balances, made by the owner to the LTC and their share of any LTC debt which they, or their associate, have guaranteed (or provided indemnities for);[26]

distributions is anything paid out to the owner by the LTC, including dividends and loans, including shareholder current account debit balances. It does not include any salary or wages received by a working owner;

income is the owner’s share of the LTC’s income (including exempt and excluded income) and realised capital gains from the current and any preceding income years (in which the company was an LTC);

deductions is the owner’s share of the LTC’s deductions in the preceding income years (in which the company was an LTC) and any realised capital losses for the current or previous income years;

disallowed amount is the amount of investments made by an owner within 60 days of the last day of the LTC’s income year if these are distributed or reduced within 60 days after the last day of the income year. This is to prevent the creation of an artificially high basis around the end of the year. To allow for normal operational cash-flow, if the reduction of investments within 60 days of the balance sheet date is less than $10,000, it can be ignored.

Example

In Table 5, the single owner advances $100,000 of capital. Revenue in each year is $60,000, of which $30,000 is exempt income and, therefore, non-taxable. Cash costs are $30,000 each year. The $30,000 of revenue that is tax exempt is distributed to the owner, so no cash is retained in the company. There are no disallowed amounts. The owner’s basis is calculated for the owner, as follows:

| Income | 30,000 |

|---|---|

| Costs | 30,000 |

| Interest | 0 |

| Exempt income | 30,000 |

| Capital gains | 0 |

| Net loss | 0 |

| Distribution | 30,000 |

However, if instead all income were to be distributed, then ultimately deductions would be limited, as follows:

Problems with the current rule

5.5 There is a general perception that the current rule is overly complex for the target LTC audience, leading to material compliance costs that are unlikely to decrease over time. The calculation applies to every owner even though most will not have their deductions constrained by it because their share of costs is less than their owner’s basis.[27] If costs exceed available funds, the shareholder can provide more equity to fund the shortfall. Nevertheless, each owner needs to make an annual calculation to determine the amount of LTC expenditure that they can deduct. Even for profitable LTCs the calculation is needed, in case the LTC eventually makes a loss, or because some of their owners may have their deductions restricted because the rule limits deductions rather than losses.

5.6 Moreover, it can restrict deductions in some situations where all costs would be deductible if earned directly by the owners; for example, when not all of an owner’s economic interest is recognised such as when there is an unrealised capital gain.

5.7 Additionally, a range of technical issues have arisen in relation to how the rule and its defined terms, such as “secured amount” and “deductions”, work in practice. Some of these issues have led to legislative amendments but further changes seem necessary.

Restricting the ability to apply losses against taxable income

5.8 Conceptually business deductions should be able to be offset against income to the extent they reflect economic costs, just as economic income (business profits and other gains that increase the value of the business) should also be taxable. Practically, there are certain restrictions on the deductions that can be claimed, just as there are restrictions on what constitutes income; for example, capital gains, which can be in effect a form of economic income, are taxed in only specific circumstances.

5.9 Given that LTCs are intended to be substitutes for direct ownership of assets in a closely held business, conceptually it seems appropriate to allow deductions when they would be deductible if the assets were owned directly. The exception would be where there are material differences in arrangements arising from incorporation that lead to excess deductions being claimed.

5.10 As an individual, the shareholder is in effect restricted to deductions that represent the economic costs that the individual has incurred. Those losses are able to be offset against an individual’s income from other sources, not just income on the investment or business.

5.11 In contrast, in widely held situations, there is generally a separation of entity and shareholder taxation so that losses cannot be transferred from the company to shareholders.

5.12 Limited partnerships straddle the dichotomy between partnerships and widely held companies, with no limits on the number of persons who can be members of a limited partnership. In this way, they can be a substitute for a standard company, which means that they should face similar restrictions; hence there are deduction limitation rules for limited partnerships to ensure that deductions are not passed through when they are in excess of what is perceived to be at risk.[28]

5.13 Although LTCs share many characteristics with limited partnerships, there are significant differences between the client groups and the purposes of LTCs and limited partnerships. In particular:

- the limited partnership rules were introduced, in part, as a response to a perceived problem for in-bound venture capital. LTCs are targeted at closely controlled businesses, primarily with a domestic focus;

- LTCs are restricted to five or fewer shareholders. Limited partnerships have no such limitation;

- LTC shareholders can, and typically will, be active in the day-to-day operation of the business. Limited partners are theoretically restricted to a passive role in the business.

5.14 These differences suggest we can be more relaxed about LTC deductions. Furthermore, LTC shareholders are taxable on debt remission income of the LTC (the remission rules are discussed later in Chapter 8). Thus there is less need for a deduction limitation rule as a base protection mechanism. Robust LTC entry or qualifying criteria will also reduce concerns about removing the rule as they are a useful initial filter for arrangements that could result in the generation of excess losses. In these circumstances, our conclusion is that the deduction limitation rule is needed only in specific instances.

When excess deductions arise that might justify restrictions

5.15 A common concern underlying the need for past restrictions on deductions has been when leveraging at the level of the company or partnership has provided significant interest deductions for the investor, without the obligation for the investor to repay the loan in the event that the project became insolvent. A variety of mechanisms were used to ensure the loans did not have to be repaid, ranging from the loan being provided on limited or non-recourse terms, to it being lent to a scheme-specific company and only secured over the assets of, and perhaps the shares in, the company. Other mechanisms included the use of put or call options over scheme assets or the use of “insurance policies”.[29]

5.16 Such ‘non-recourse’ schemes have typically involved:

- a high-risk activity with apparently optimistic or unrealistic future sales projections, and property, including intangible and intellectual property, that is difficult to value;

- the use of non-residents, tax-exempt organisations or tax loss companies so that any income is effectively exempt from New Zealand income tax;

- investors putting relatively small amounts of their own money into the schemes but the promoter arranging instead for the investors to have access to loan money that is used to purchase high-value assets that diminish in value, at least for tax purposes, over time.

5.17 Specific “money-at-risk” rules[30] were enacted in 2003 to address the base erosion impact posed by these schemes, but those rules are very specific and predate LTCs. These rules were targeted at mass marketed schemes that typically, but not always, used LAQCs. The overall response to these schemes, including the use of other anti-avoidance rules in the Income Tax Act, has arguably been effective as mass marketed tax driven schemes since that time have been limited.

5.18 There is the general anti-avoidance rule in section BG 1 that enables the Commissioner to void a tax avoidance arrangement for income tax purposes and to counteract a tax advantage that a person has obtained from or under a tax avoidance arrangement. Furthermore, the anti-avoidance rule in section GB 50 relating to the valuation of partners’ transactions is potentially of relevance, with some modification.

5.19 In considering changes in relation to the anti-avoidance rules, we have been mindful that any proposals need to avoid replacing one set of compliance costs with another. Ultimately, the vast majority of LTCs and owners are conducting legitimate business activities and any resultant deductions are genuine.

Arrangements involving partners

5.20 Section GB 50 replaces consideration paid by a partner with a market value amount when the arrangement has the purpose or effect of defeating the intent and application of the partnership tax rules (in subpart HG).

5.21 This requirement was designed to protect the tax base, with the concern being the transfer of assets in and out of a partnership at under- and over-value, for tax benefits. For example, a controlling partner could introduce valuable assets into a partnership to accelerate their own tax deductions, say on depreciable property.

5.22 The rule is not intended to affect situations where non-market transactions between partners occur legitimately. It is therefore expressed as a specific anti-avoidance rule that essentially deems a transaction to have occurred at market value when the transaction is subject to an arrangement entered into to avoid tax.

5.23 Given that the LTC rules are based on the partnership rules, it seems logical to extend section GB 50 to include LTCs. This would at least address the valuation aspect, which is a likely feature of schemes that involve excessive deductions, irrespective of whether they are mass-marketed. Extending this rule to LTCs may, however, highlight some subtle differences. For example, a nil interest loan from a partner might be squared up through an adjustment to partners’ profit shares. Such a profit adjustment cannot be readily done in the case of LTC shareholders given that allocations are according to shareholdings, although some adjustment to shareholdings may be feasible to achieve a similar outcome. Feedback is sought on this point and the general application of the section GB 50 rule.

Partnerships of LTCs

5.24 Partnerships of LTCs are used in certain business ventures. In effect, this is a widely held investment structure and replicates a limited partnership, but with the added advantage of each partner being able to be active in the business in some way.

5.25 From a policy perspective there is little cause for concern over partnerships of LTCs. However, this situation changes if the deduction limitation rule as it applies to LTCs is removed. Such a result has the potential to see limited partnerships being superseded by partnerships of LTCs as a preferred structure for widely held investments.

5.26 Limited partnerships have been designed as a structure to aid widely held investment where flow-through treatment is considered desirable. It therefore seems inconsistent to have an alternative structure that replicates the more favourable aspects of limited partnerships but without the restrictions that apply to them.

5.27 The deduction limitation rule should therefore be retained for partnerships of LTCs. Ideally this would be when there are more than five look-through counted owners in aggregate across the LTCs in the partnership. In other words, there would be more owners than would be allowed if the partnership’s activities were undertaken by a single LTC. Basing the application of the test on the number of combined owners, may, however, cause practical difficulties. This is because it puts the onus on each LTC to know how many owners there are in the other LTCs in the partnership which becomes complicated if there are trusts and family groups to consider. This may mean that, for simplicity, all partnerships of LTCs would need to apply the test. Feedback on this point is invited.

Transitional arrangements

5.28 The proposed removal in most cases of the deduction limitation rule raises the issue of what to do with those deductions that are limited up to the removal of the rule and have therefore been carried forward. Such restricted deductions average around $7m a year and are expected to have accumulated to $35m by 2016–17, which translates to a fiscal cost of $12m, spread over two years. Such deductions would become unrestricted from the 2017–18 income year and could, therefore, be offset against owners’ other income from that income year.

Technical changes to the deduction limitation rule

5.29 We are proposing some technical changes to the deduction limitation rule to clarify its application for those who would continue to be covered by it. The changes involve:

- a balance sheet based starting point for the calculation of “owner’s basis” for companies that enter the LTC regime;

- the inclusion of unrealised gains on real property; and

- further consideration of the treatment of guarantees, requiring among other things, that the guarantor be a person of substance and not the LTC itself.

5.30 Submissions are welcome on any other aspects of the rule that are causing concern. In the meantime, officials will continue to consider the detail of this rule with the aim of further simplification.

Balance sheet based starting point

5.31 At the moment the tax law is unclear how the term “investments” in the formula is to be calculated in respect of an existing company that elects into the LTC regime. For example, the company may have been in existence for many years. A balance sheet based approach, with adjustments (such as reversal of revaluations except in respect of real property), would provide a clean starting point.

Inclusion of unrealised capital gains into the current formula

5.32 An owner has money at risk even in relation to gains on capital assets that have not been realised. When the assets are intangible, valuing those gains with confidence can be problematic. However, in the case of real property, revaluations are already provided for in the mixed use assets rules in the Income Tax Act. Consequently, we are proposing that revaluations of real property, calculated in a similar fashion to the mixed use assets rules, be added to “owner’s basis”.

Possible alternative rule

5.33 We did consider whether a more fundamental change to the rule was needed, while retaining the principle of denying excessive deductions. Our conclusion was that any rule is inevitably going to be detailed given the variety of assets, liabilities and businesses that might be included in a LTC. The existing rule has been in place for several years in which case LTCs will be familiar with it and a new rule would involve another teething period. Furthermore, the proposed removal in most cases of the deduction limitation rule reduces the benefits from any fundamental rewrite of the rule. It seems preferable, therefore, to instead make some minor adjustments to the existing rule, as outlined above. However, it may be helpful to at least summarise some of our thinking on some possible alternative ways of designing a rule. This is included in Appendix 2.

[26] The rules include various definitions in relation to guarantors, owner’s associates and secured amounts.

[27] Around one percent of LTCs reported non-allowable deductions carried forward in 2013 – see Appendix 1.

[28] Internationally, limited partnerships pose substantial risks for domestic taxation and out-bound investments, with a number of jurisdictions placing restrictions on them, as a way to counteract mass-marketed tax shelter schemes. In such schemes, tax deductions often greatly exceeded the investments made by the “investors” with profits to investors often being entirely generated by the tax system. Limiting tax deductions to economic losses makes perfect sense in such situations.

[29] It needs to be borne in mind, however, that the existence of a non-recourse loan, in a bona fide business arrangement, need not in itself be a problem. The same amount of interest would be deductible whether the loan was to the shareholder, or to the company, with or without a guarantee. In an arm’s length transaction, with no artificial arrangements, a financial institution would presumably only be willing to provide a loan secured against the assets of the company in situations where the probability of default was small and the assets were tangible.