Chapter 7 - GST treatment of “available for use” periods

7.1 Tax cascades arise when a supplier of goods or services cannot recover the GST paid on the acquisition of goods or services. To prevent tax cascades the GST system provides a person with the ability to recover GST paid in respect of a supply when they acquire goods or services for business purposes or, in GST terms, “for making taxable supplies”. This ensures that the economic incidence of the tax is removed on most business purchases, and that GST taxes consumption and not production.

7.2 New GST apportionment rules were introduced on 1 April 2011. Under these rules, when a GST-registered person incurs an expense that was subject to GST, the person is able to deduct input tax on acquisition only to the extent to which goods or services are used for, or are available for use in, making taxable supplies.[4] In subsequent years, a person may be required to adjust the deduction claimed if the extent to which the asset is actually used for making taxable supplies is different from the intended taxable use of the asset. A number of exemptions are available to relieve a person from the requirement to make an adjustment if the amount of tax involved in the adjustment is minimal.

7.3 GST is imposed at a set rate on the value of a supply. The amount of GST involved in a supply therefore increases proportionally to the value of the supply. For high-value assets such as real property, it is particularly important to ensure that rules that regulate the ability to deduct input tax are clear in respect of the proportion of input tax that may be deducted.

7.4 Although for the most part such clarity exists, closer scrutiny is required when a mixed-use asset remains unused for a particular period. The GST issues for mixed-use assets are similar to those that arise for income tax which are discussed in the preceding chapters.

Application of the GST rules

7.5 To register for GST, either voluntarily under the $60,000 registration threshold or compulsorily over the threshold, a person has to carry on a taxable activity. A taxable activity is defined in the GST Act as an activity carried out continuously or regularly and that involves supplying, or intending to supply, goods and services to someone else for a consideration but not necessarily for profit. Whether a person is carrying on a taxable activity is a question of fact and degree in each case and will involve an examination of all circumstances.

7.6 It is generally accepted that the requirement for a taxable activity to exist does not provide a high barrier to GST registration, thus allowing many taxpayers with a fairly small level of taxable activity to register for GST voluntarily. One benefit of this, and the related ability to deduct input tax, is that small businesses are able to grow and become more competitive. On the other hand, in mixed-use asset situations it is important to ensure that the level of input tax deductions is an appropriate reflection of the relative taxable and non-taxable use of the asset.

The issues

7.7 The apportionment rules allow a person to claim input tax deductions to the extent that the goods or services are used for, or are available for use in, making taxable supplies.

7.8 In most cases, goods or services are actively used for either a taxable or non-taxable purpose or a combination of those purposes. In those cases, identification of the extent of taxable use of those goods or services can be based on the taxpayer’s records of the asset’s use for making taxable supplies.

7.9 In some cases, the goods or services may be available for use in, rather than being actively used for, making taxable supplies. For example, a commercial property developer may purchase raw materials that they intend to use in construction of a property at some time in the future. Although for a period of time the raw materials are not actively used for making taxable supplies, the property developer is still able to claim the related input tax deductions because the materials are “available for use” in making taxable supplies and will be actively used for that purpose at some time in the future.

7.10 In other situations, however, it may be difficult to determine the extent of taxable use of goods or services. For example, during a year, a holiday house may be used by its owners as a holiday residence for three months, be rented out[5] for five months, and be advertised for rent, but remain vacant, for the remaining four months. If the owner is registered for GST and the rental activity is subject to GST, a question arises over what extent the owner should be able to claim input tax deductions in respect of the house. Although there has clearly been taxable use for the five months when the property was actually rented out, it is uncertain whether the use in the period when the property was vacant should count towards the taxable use for deduction purposes.

7.11 The principal uncertainty stems from the fact that although the holiday house is available for use in making taxable supplies during the vacant period (because it is advertised as being available for rent), it is similarly available for use for private purposes during the same period.

7.12 Neither current nor previous GST legislation has provided express guidance regarding the methodology that should be used for apportioning between taxable use and non-taxable use in these situations. One may argue that the availability of assets for use in making taxable supplies should take precedence and that input tax deductions should therefore be allowed in full for vacant periods. This is, however, difficult to justify as a default rule considering that private use can be the dominant reason for buying a holiday house. Instead, officials consider that the decision as to whether non-use of a holiday house should be treated as taxable use should be based on the dominant use of the asset during a relevant adjustment period.[6]

7.13 Officials view this methodology would produce a balanced outcome and provide a degree of protection to the revenue base. Certainty in the methodology used is desirable to enable taxpayers to comply with the legislation, to reduce their compliance costs in doing so, and to ensure consistent application of the apportionment rules across taxpayers.

Assets subject to clarification

7.14 Chapter 5 discusses, in relation to the income tax rules, the types of assets used for mixed business and private purposes that should be covered by the new methodology. The introduction of a conceptual definition that would target assets where significant income tax deductions are an issue – such as holiday houses, boats and aircraft – has been recommended. To be covered by the proposed methodology, an asset must satisfy the following elements:

- the asset is rented on a short-term basis; and

- the asset is unused for a reasonable proportion of the year; and

- for assets other than land the cost is above a minimum threshold (possibly $50,000).

7.15 It has also been suggested that the current rules in relation to logbooks for motor vehicles and established practice around the use of the part of a home for earning income would continue to apply.

7.16 The GST apportionment rules, as mentioned earlier, allow input tax deductions for goods and services that are not used for, but are available for use in, making taxable supplies. This treatment of non-use periods recognises that most goods or services are purchased by a GST-registered person for business reasons and will, at some point, be used for making taxable supplies. In these circumstances, the presence of an incidental private use may not unduly affect the deduction of input tax for the period of non-use.

7.17 Some assets, however, have an inherently significant private element for which the application of the ordinary apportionment principles might not provide an appropriate outcome. Three key examples of such assets are holiday houses, private boats and aircraft. These assets are usually purchased by their owners with the intention of using them for private purposes and any commercial rental/hiring activity, at least in some cases, results from a desire to recoup some of the purchase price paid in relation to the asset rather than an intention to run a commercial operation.

7.18 These assets – holiday houses, boats and aircraft – account for the majority of assets that fall under the conceptual definition recommended for income tax purposes. To provide consistency between the taxes, one approach would be to adopt the conceptual definition for the purposes of GST.

7.19 The advantage of the conceptual definition approach is that it ensures that the same methodology is used for all assets that satisfy the relevant tests. The disadvantage of the approach is that it may be difficult to state with certainty which types of assets would be included under the definition. As a result, it may include some assets for which the methodology is not appropriate.

7.20 An alternative approach would be to apply the new methodology to holiday houses, boats and aircrafts only. Although this approach would provide taxpayers with certainty over application of the new rules, it may also exclude assets that are conceptually similar to those listed.

7.21 Officials seek views on which of these two approaches is preferable for GST purposes.

Possible approach

7.22 In the context of assets such as holiday houses, boats and aircraft, input tax would either be incurred on the purchase of those assets or be embedded in the purchase price if the assets are second-hand goods.[7]

7.23 Taking into consideration the proposed income tax approach, in circumstances when an empirical determination of taxable use is not possible, such as when a mixed-use asset is not used in a particular period, it is reasonable to determine a preferred treatment by examining the total use of the asset during a relevant adjustment period.

7.24 A typical situation is where throughout a considerable part of an adjustment period a holiday house is used for making taxable supplies (that is, rented out), while its private use is minimal. In these situations, it seems fair to deem the time when the asset is not used, but available for use in, making taxable supplies as the time when the asset was actually being used for taxable purposes. The assumption is that the taxpayer would indeed have rented out the asset if they could.

7.25 In a different scenario, an asset may be rarely used for making taxable supplies and much more often used for private purposes. In this scenario, we can conclude that the taxable use is merely incidental to the private use of the asset, and that the period of non-use should be treated in the same manner as a period of private use.

7.26 Finally, there will be situations when an examination of the overall activity of an asset might not provide a definitive answer on which use – taxable or private – has been predominant. In these circumstances, it may be reasonable to allow an apportionment of periods when the asset is not used.

Three-outcome approach

7.27 The above outcome would be achieved by adopting for an adjustment period a similar apportionment methodology to that described as the three-outcome approach in chapter 3 and chapter 4. The proposed approach requires a person to answer a number of questions about the use of their asset which are designed to provide an indication about whether the use of the asset, as a whole, is better classified as taxable, private or a mixture of the two.

7.28 The three-outcome approach would assist a GST-registered person to identify the extent of taxable use of those assets, as follows:

- Predominant private use: A person’s taxable use of the asset will be limited to the periods when an asset is actually used for making taxable supplies. This would occur when the asset is not rented/hired out for more than 62 days in an adjustment period, and/or the person does not make a genuine effort to rent/hire out the asset during periods when the asset is not actively used (assuming that the asset can reasonably be used in those periods).

Example

A holiday is rented out for 30 days during a 12-month adjustment period. The house’s taxable use for the adjustment period is 8 percent (30/365) and the owner may apportion the input tax in respect of the house accordingly.

- Predominant business use: A person’s taxable use will include periods when the asset is actually used for making taxable supplies and periods when the asset was not used but available for use in making taxable supplies. This would occur when the asset is rented/hired out for more than 62 days in an adjustment period, and the person makes a genuine effort to rent/hire out the asset during periods when the asset is not actively used (assuming that the asset can reasonably be used in those periods), and the actual private use is less than 10 percent of the active taxable use.

Example

During a 12-month adjustment period, a holiday house is rented out for 120 days, used by the owners for private purposes for five days and advertised for rent for the remaining 240 days. Since the private use of the house is less than 10 percent of the rental use of the house, the person is able to treat the house as being used for taxable purposes for 360 days (120 + 240 days). The person’s actual taxable use of the house during the adjustment period is, therefore, 98 percent (360/365) and the owner may apportion the input tax in respect of the house accordingly.

- Mixed-use: A person’s taxable use will include periods when the asset is actually used for making taxable supplies and a proportion of time when the asset is not used, but available for use in making taxable supplies. This would occur when the asset is rented/hired out for more than 62 days in an adjustment period, and the person makes a genuine effort to rent/hire out the asset during periods when the asset is not actively used (assuming that the asset can reasonably be used in those periods), and the actual private use is 10 percent or more of the active taxable use.

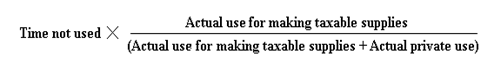

The proportion of time that may be attributable to the use of an asset for taxable purposes during the time of non-use will be calculated by reference to the apportionment formula:

Example

During a 12-month adjustment period a holiday house is rented out for 100 days, used by the owners for private purposes for 60 days and advertised for rent for the remaining 205 days.

The owner of the house may treat the 100 days that the house was actually rented out as use for making taxable supplies. The owner may also treat a proportion of the period when the house was vacant as use for making taxable supplies. This proportion is calculated using the formula:

205 x 100/(100+60) = 128

Therefore, the owner may treat 128 of 205 vacant days as attributable to making taxable supplies. In total, the house is being used 228 days (100 + 128 days) for taxable purposes during the adjustment period. As a consequence, taxable use of the house in the relevant adjustment period is 62 percent (228/365 days) and the owner may apportion the input tax in respect of the house accordingly.

7.29 Owing to the use of these “bright-line” tests, the three-outcome approach should not be too complicated or give rise to undue compliance or administration costs. At the same time, the three-outcome approach does provide for a variety of outcomes for identifying taxable use, therefore increasing the chance that the final outcome is suited to the individual circumstances of a taxpayer. On the other hand, a bright-line test will at the margins create differing outcomes for not dissimilar situations. This is an inevitable outcome of providing this kind of certainty.

Two-outcome approach

7.30 The second potential apportionment methodology suggested in Chapter 3 is the two-outcome approach. Depending on whether certain conditions are satisfied, under this approach a taxpayer may be deemed to either have been using or not have been using the asset for taxable purposes during the time of non-use. No apportionment of periods of non-use would be possible under this approach.

7.31 In the GST context, to be able to treat an asset as being used for taxable purposes during periods of non-use, the following conditions would need to be satisfied during an adjustment period under the two-outcome approach:

- The asset must be used for actually making taxable supplies (rent/hire) for more than 62 days in an adjustment period.

- Actual personal use must be less than 15 percent of active taxable use.

- Genuine efforts must be made to make taxable supplies for all non-use periods for which the asset can reasonably be used, evidenced by marketing for those periods and positive responses to enquiries.

7.32 By allowing only two-outcomes, this approach is simpler than the three-outcome approach. On the other hand, by either fully allowing or disallowing a period of non-use as use of the asset for taxable purposes, the approach may potentially provide an unfair or arbitrary result.

7.33 In the absence of an apportionment mechanism for non-use periods under the two-outcome approach, fewer taxpayers would be able to treat any proportion of non-use as being use for making taxable supplies than under the three-outcome approach. At the same time, some taxpayers would be able to claim the full period of non-use as use for making taxable supplies rather than being required to apportion that period.

Conclusion

7.34 Either of the two approaches discussed in this issues paper in respect of deductibility of expenses for income tax purposes may potentially be adopted to resolve the uncertainty with the GST apportionment – at least, for holiday homes, boats and aircraft. Officials therefore seek views on these two approaches for GST purposes or whether there are other approaches that should be considered.

Submission points

- Do you consider that the methodology for treatment of periods of non-use should be the same for the purposes of both GST and income tax?

- How should assets subject to the proposed methodology be defined: conceptually or by list?

- Which of the suggested approaches (three- or two-outcome) is preferable for GST purposes?

- Are there any other approaches that should be considered?

4 Some second-hand goods are not subject to GST on sale, but may still be treated as having GST imbedded in the purchase price. “Second-hand goods deduction” will be available in respect of those goods.

5 Following the narrowing of the definition of “dwelling”, effective from 1 April 2011, a supply of accommodation in a holiday house would normally be treated as subject to GST.

6 Under the GST apportionment rules, an “adjustment period” is a period at the end of which a person must evaluate their taxable use of goods or services to ensure that a correct amount of input tax has been deducted. An adjustment period is generally a period of one year.

7 If a purchase of land is zero under section 11(1)(nb) of the GST Act, a “nominated GST component” used for apportionment purposes (sec 23(3J)), will be 21D(2)(a)).