Chapter 3 - Framework for the allocation of expenditure between uses

3.1 The suggested new rules categorise mixed-use assets into different groups based on the underlying use of the asset, and prescribe the level of deductions that owners in each group can claim. This chapter considers two alternative frameworks for the proposed changes, namely, the three-outcome approach and the two-outcome approach.

3.2 The two approaches are explained and evaluated below. The details of the tests which make up each approach are discussed in the next chapter.

Three-outcome approach

3.3 The three-outcome approach uses two tests to distinguish between three groups of mixed-use asset. The rules prescribe different levels of deductions that owners in each group are able to claim.

3.4 The following outlines each group and the level of deductions each group is able to claim:

- The private-focused group: The combination of effort and success at earning income is low. In this case, the owner is only able to claim expenditure which relates to the actual income-earning use of the asset, and no deduction can be claimed for expenditure that relates to the time the asset is not used.

- The genuine mixed-use group: The effort and success in earning income is reasonably high, but there is a greater level of private use than the income-focused group. In this case, the owner is able to claim expenditure which relates to the actual income-earning use of the asset, and a proportion of expenditure that relates to the time the asset is not used can be claimed.

- The income-focused group: The effort and success in earning income is reasonably high, and private use is limited. In this case, the owner is able to claim expenditure which relates to the actual income-earning use of the asset, and all the expenditure that relates to the time the asset is not used can be claimed.

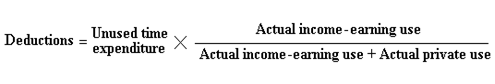

3.5 The genuine mixed-use group is able claim a proportion of expenditure that relates to the time the asset is not used under a general apportionment rule. The apportionment rule would use the following formula:

Example

Jill uses her holiday home herself for five weeks a year and rents it for five weeks a year. Expenditure relating to the 42 weeks of the year that the holiday home is unused (unused time expenditure) is deductible at a rate of 50% calculated as five weeks income-earning use divided by 10 weeks of total use.

Two-outcome approach

3.6 The three-outcome approach can be simplified by removing the genuine mixed-use group under which the apportionment calculation is carried out. This creates the two-outcome approach. This would leave only the private-focused group, under which unused time is not deductible at all, and the income-focused group, under which all expenditure associated with unused time is deductible.

3.7 All mixed-use assets would be categorised as follows:

- For those who actively market their asset and have a reasonably low level of private use, deductions would be available for all unused time expenditure.

- For all others, no deductions would be available for unused time expenditure as the asset has a private-focused outcome.

Comparison between the two approaches

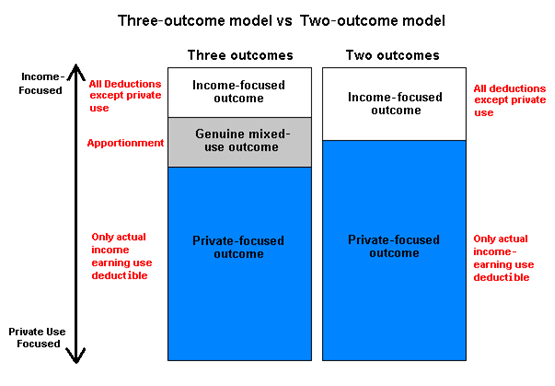

3.8 An important difference between the three-outcome model and the two-outcome model is that the test to qualify for the income-focused group would be easier to pass under the two-outcome model. This difference is necessary because the consequence of not falling into the income-focused group in the two-outcome model is denial of all deductions which relate to the time the asset is unused. This can be compared with the three-outcome model which provides apportionment as an outcome for those who combine significant income-earning activity with some private use.

3.9 This difference is explained in the following diagram:

3.10 The number of people for whom the income-focused outcome would apply is deliberately larger under the two-outcome approach than under the three-outcome approach. This means those who have a significant income-earning focus but some private use of their asset are likely to prefer the two-outcome approach.

3.11 The reverse is true for those who have an income-earning focus but a larger amount of private use. They are likely to be able to claim a deduction for a proportion of their unused time under the three-outcome approach (where the genuine mixed-use outcome will apply), but no deduction under the two-outcome approach (where the private-focused outcome will apply).

3.12 What these two differences show is that neither the two-outcome nor the three-outcome approach is, overall, more generous than the other. Those who have either a strong income-earning focus or a strong private use focus will receive the same treatment under either proposal, and those in the middle may prefer one or the other depending on exactly where they fall.

3.13 The three-outcome approach presents a reasonably sophisticated solution that aims to match asset owners’ individual circumstances with some degree of precision. Compared with the two-outcome approach, there are fewer grounds for arguing that its treatment of asset owners is unfair. However, these advantages must be weighed against the disadvantage of the additional complexity. The three-outcome approach has two tests, rather than the single test of the two-outcome approach. It also includes the apportionment formula, which delivers apportionment percentages specific to each asset owner’s circumstances, but which in itself is a reasonably complex tool.

3.14 By contrast, the two-outcome approach is relatively simple. Only one test need be applied, and the result is that asset owners fall into one of two categories. However, this simplicity results in some degree of arbitrariness. An asset owner at the margin can easily switch from being entitled to deductions for all unused time expenditure, to being entitled to no deductions for any of it, which is a dramatic difference.

Submission point

Each of the approaches set out above has advantages and disadvantages, and at this stage officials have no strong preference for one over the other. Accordingly, submissions are invited on whether, at a framework level, the two-outcome or three-outcome approach is preferred. Leaving aside the detail of the tests, do you prefer the three-outcome or the two-outcome framework? Why?