Extending the active income exemption to non-portfolio FIFs

Regulatory impact statement for the Taxation (International Investment and Remedial Matters) Bill introduced in October 2010.

Agency Disclosure Statement

This Regulatory Impact Statement has been prepared by Inland Revenue.

It provides an analysis of different options for reforming the international tax rules in order to remove a barrier to offshore expansion by New Zealand businesses. It also analyses options for taxing substantial stakes in foreign companies held through portfolio investment entities (PIEs) and how to deal with a very small number of inherited foreign shares which are not currently taxed.

The Government recently introduced a tax exemption for active income earned by foreign companies that are controlled by New Zealand investors (controlled foreign companies, or CFCs).

We propose that the active income exemption be extended to interests of 10% or more in foreign companies that are not controlled by New Zealanders (foreign investment funds, or FIFs).

The proposal will reduce tax and compliance costs on many offshore investments but increase compliance costs on others.

The estimated fiscal cost of the active income exemption ($10m per annum), is indicative of the expected reduction in tax payable for New Zealand businesses with non-portfolio interests in FIFs.

Compliance costs for New Zealand investors with a 10% or greater interest (e.g. shareholding) in FIFs outside the eight grey list countries will be reduced, as long as those FIFs are substantially engaged in active business and the investor has access to sufficient information to apply the active business test (i.e. confirm that the FIF has less than 5% passive income). Investors will be able to use consolidated accounting information to apply the active business test to a chain of related FIFs. Because it can be easier to get consolidated information, this should enable more investors to be able to use the active income exemption.

Investors with a 10% or greater interest in a FIF in a grey list country, other than Australia, will experience an increase in compliance costs, because they will have to obtain information to apply the active business test and, in cases where the investor cannot apply or pass the active business test, calculate an amount of income tax to pay on the FIF’s income. We have endeavoured to minimise these compliance costs by allowing investors to use consolidated accounting information to apply the active business test to a chain of related FIFs and by allowing investors to calculate FIF income using an assumed 5% rate of return (i.e. the fair dividend rate method) in cases where they cannot pass the active business test.

Officials have undertaken extensive consultation about the issues discussed in this statement. An issues paper was released in March 2010 and 19 submissions were received from accounting and legal firms and from businesses with offshore operations. Face-to-face discussions were subsequently held with tax professionals and interest groups. As a result of these discussions, significant changes were made to policy proposals. One change lowered the threshold for use of the active business test from a 20% interest in an FIF to a 10% interest. A second change allows New Zealand investors to use consolidated accounting information for groups of FIFs, even if those FIFs are in different countries. These changes are expected to make the active income exemption available to more investors and make the active business test more workable in practice.

The proposals do not impair private property rights, restrict market competition, reduce the incentives on businesses to innovate and invest, or override fundamental common law principles.

Dr Craig Latham

Group Manager, Policy Advice

Inland Revenue

2 August 2010

PROBLEM DEFINITION AND STATUS QUO

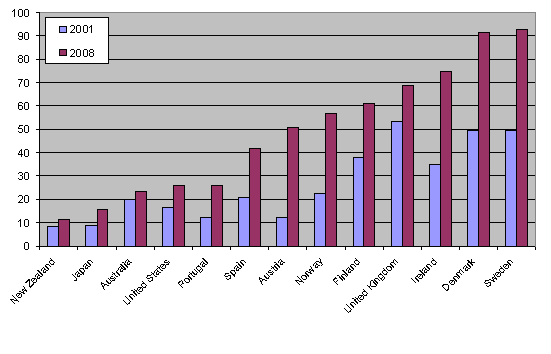

1. Compared to businesses in other developed economies, New Zealand businesses appear to be less engaged in operating outside of their home country. This is illustrated by figure 1, which displays the stock of outbound foreign direct investment as a proportion of gross domestic product.

Figure 1: Outbound Foreign Direct Investment as a percentage of Gross Domestic Product

2. This suggests that New Zealand may be missing out on the economic benefits associated with businesses operating subsidiaries, joint ventures and other substantial investments in foreign markets. These benefits can include improved market knowledge, skills transfer and access to customers and suppliers. This may facilitate export growth or increased high-value research, design and management activities in New Zealand.

3. There are a range of possible factors that could contribute to New Zealand’s relatively poor outbound Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) performance (such as industrial structure, distance from markets, etc). Tax may also be one factor.

4. New Zealand’s international tax rules can impose higher tax or compliance costs on offshore operations than those faced by competing businesses operating in the same foreign country. In many cases, a New Zealander who makes investments in a foreign country needs to not only comply with the tax rules of that country, but also attribute income using New Zealand tax rules (and potentially pay further tax in New Zealand). In contrast, many other countries reduce or eliminate the additional tax or compliance burden created by a second layer of tax by exempting offshore income that is earned by active businesses. This may create an incentive for New Zealand companies undertaking or considering active business ventures outside New Zealand to relocate their headquarters to countries with more favourable tax rules.

5. For this reason, the Government recently introduced an exemption for active income earned by foreign companies that are controlled by New Zealand investors. The active business exemption puts New Zealand businesses expanding into foreign jurisdictions on a similar tax footing compared to their competitors in those countries.

6. Firms expand beyond New Zealand through a variety of structures, and New Zealand companies wanting to expand overseas may have good commercial reasons for not operating through a wholly or majority-owned subsidiary. As with the former CFC rules, the existing FIF rules can impose additional tax and compliance costs on New Zealand businesses that operate in offshore markets through joint ventures or other non-controlling stakes in foreign companies.

7. The proposal is therefore to expand the exemption to non-portfolio FIFs.

PIEs with substantial stakes in foreign companies

8. A related issue is whether portfolio investment entities (PIEs) should be able to access the active income exemption. The problem is that if PIEs were able to access the active income and foreign dividend exemptions they would be able to pass foreign income through to their members with no New Zealand tax. In contrast, foreign income passed through an ordinary (non-PIE) company would be subject to New Zealand tax.

Inherited foreign shares

9. Another issue relates to a very small number of foreign shares that were inherited prior to the introduction of inheritance rules in October 2005. Some investors claim that these shares have a nil cost. This means that they qualify for the $50,000 “de minimis” exemption from the FIF rules, even though the actual cost of the shares to the person who purchased them (before the bequest) may be higher than $50,000. It is not appropriate that these shares continue to be exempt from the FIF rules.

OBJECTIVES

10. The main aim of the proposals outlined in this paper is to remove a barrier to offshore expansion by New Zealand businesses, by reforming the taxation of international investments.

11. A secondary objective is to ensure that similar types of foreign investments are taxed consistently. This objective motivates the PIE and inherited foreign share proposals.

REGULATORY IMPACT ANALYSIS

Full exemption or active income exemption?

12. One way to reduce tax and compliance costs imposed by New Zealand’s international tax rules would be to exempt all types of income derived from a non-portfolio interest in a FIF. The main problem with this approach is that it would create opportunities and incentives for taxpayers to shift “passive” income (i.e. highly mobile income such as interest, rent or royalties) into low-tax jurisdictions to minimise their tax liabilities. This type of offshore investment is unlikely to enhance New Zealand’s economic potential or wellbeing but could result in a large loss of tax revenue.

13. For this reason, the CFC rules make a distinction between active and passive income. Restricting the exemption to active income (or active businesses) can be an effective way to reduce tax and compliance costs in those cases where the economic benefits are highest and the risks to the tax base are low.

14. The existing FIF rules already provide a full exemption for interests of 10% or more in FIFs that are located in eight grey list countries. The grey list exemption is based on an assumption of comparable taxation in these countries. Although this assumption generally holds for active business income, it cannot be relied upon for passive income. It therefore makes sense to replace the grey list exemption with an active income exemption.

Entity, transactional or hybrid approach?

15. There are three possible ways to implement an active income exemption:

- The entity approach looks at whether the company is active or passive. Once categorised, all of the income of the company is taxed in the same way, regardless of the nature of the income derived.

- The transactional approach examines each item of income derived by a CFC to determine whether it produces passive income or active income.

- A hybrid approach applies an entity test to the foreign company’s activities. Using financial accounts, the active business test is based on the amount of gross income of the company that is passive. If passive income is less than 5% of gross income, the New Zealand-resident shareholder is not taxed on any income from the shareholding. If passive income is more than 5%, then only passive income is attributed to the shareholder on a transactional basis – i.e. active income continues to be exempt from attribution.

16. The main concern with an entity approach is that it can lead to significant amounts of passive income being exempted. The entity approaches used in other countries generally have a high tolerance (up to 50%) for passive income or assets. This is problematic as passive income can be shifted offshore to avoid or defer New Zealand tax. At the same time, for those entities that fail the test, all income, including active income, is taxed on accrual.

17. A pure transactional approach would avoid these problems, but would involve significant compliance costs for investors in entities with mainly active income.

18. A hybrid approach was adopted in the new CFC rules, as this was considered the best way to minimise compliance costs for active businesses whilst preserving the ability to tax entities that earned significant amounts of passive income.

19. It is proposed that a hybrid approach should also apply to FIFs. Applying the same set of rules to FIFs and CFCs would ensure that commercial decisions are not distorted according to whether the investor preferred the tax treatment under the CFC or FIF rules. It would also avoid the changes in tax treatment that could otherwise arise when a FIF becomes a CFC (or vice versa). Finally, it would reduce the overall complexity of the international tax rules and so make the exemption easier for companies and advisors to understand and operate.

What type of FIFs should be eligible?

20. Another key consideration is determining what type of investors should be eligible for the active income exemption. For example, if the exemption applied to portfolio interests, there would be a substantial cost for little additional economic benefit. This is because portfolio shareholders typically focus on investment returns, rather than seeking to directly influence management decisions or exchange knowledge and skills that may help grow a New Zealand business. Also, if the active income exemption was to apply to portfolio FIFs, it could create a bias toward investing in offshore stock markets, as opposed to domestic investments. Excluding portfolio investors from the scope of the exemption is consistent with international norms.

21. This leaves investors with shareholdings of between 10% and 50% in a foreign company that is not a CFC. Some of these investors are actively involved in managing the foreign company (akin to an investor in a CFC), while others are only interested in getting a return from share prices or dividends (akin to a portfolio investor). Accordingly, it is proposed that these investors would have a choice of applying the active income exemption or the portfolio FIF methods. This way, treatment is flexible enough to allow for differing levels of access to information – active investors should be able to get enough information to apply the active income exemption, while passive investors will have enough information to apply the portfolio FIF rules. This also means that the tax treatment of an investment is likely to roughly reflect the type of investment.

PIEs with substantial stakes in foreign companies

22. For the reasons mentioned above it would not be appropriate if portfolio investors were able to access the exemption by investing with other portfolio investors through a portfolio investment entity (PIE). We considered three options for taxing non-portfolio foreign investments held through PIEs.

23. The first option would be to prevent PIEs from holding investments of 10% or more in foreign companies. This would be more restrictive than the existing rules where PIEs are required to hold less than 20% in companies in which they invest (other than other PIEs or PIE-equivalents).

24. The second option would be to tax dividends that PIEs receive from foreign companies. Under this approach active foreign income would be taxed when it was distributed to the PIE, as opposed to when it was earned offshore (because of this, passive foreign income could be taxed twice in New Zealand).

25. A third option would be for PIEs to apply the same tax rules to their non-portfolio investments in foreign companies as they apply to portfolio investments. This would mean that they would not be able to access the active income exemption and would generally use the fair dividend rate method. This is consistent with how these investments would be treated if the investors in the PIE held the interests in the foreign company directly. This third option is recommended as it does not further restrict the investments that PIEs can hold, it leads to a consistent tax treatment and was also preferred by submitters.

Inherited foreign shares

26. The problem of some inherited foreign shares not being subject to tax arises due to the fact that these shares were inherited at a nil cost. A sensible way to address this problem is to require a deemed sale and reacquisition of the affected shares at market value. The affected taxpayers would be taxed only if this caused them to breach the $50,000 threshold and any tax liabilities would apply only to years after the amendment is made.

Impact on tax costs and competitiveness

27. The active business exemption puts New Zealand businesses expanding into foreign jurisdictions on a similar tax footing to their competitors in those countries. The estimated fiscal cost of the active income exemption ($10m per annum), is indicative of the expected reduction in tax payable for New Zealand businesses with non-portfolio interests in FIFs.

Impact on compliance costs

28. The proposal will reduce compliance costs for many holders of offshore investments but increase compliance costs for others.

29. There will be a reduction in compliance costs for investors with a 10% or greater interest in FIFs outside the eight grey list countries. These investors will now be able to use the active business test (which will involve lower costs than performing a full branch equivalent calculation) or alternatively use an assumed 5% rate of return.

30. There will be an increase in compliance costs for investors with interests of 10% or more in FIFs that are in grey list countries. These investors will incur additional costs if they elect to apply the active business test, in obtaining accounting information and calculating measures of passive and total income. In some cases there may not be sufficient information to apply the active business test, in which case the investors will have to calculate and attribute FIF income under another method. The increase in compliance costs is partly alleviated by allowing investors to calculate FIF income using an assumed 5% rate of return.

31. There will be no change in compliance costs for investors with 10% or greater interests in FIFs in Australia, as these investors will continue to benefit from an automatic exemption.

32. The expansion of the interest allocation rules to investors in FIFs who apply the active income exemption will increase compliance costs for a small number of taxpayers. Many outbound investors will already be subject to the interest allocation rules by virtue of having a CFC interest. Businesses with less than $1m of interest deductions or less than 10% of their assets offshore are exempt from having to apply the interest allocation rules and so will not incur additional compliance costs.

33. As part of the change in the FIF rules, including the introduction of the active income exemption for non-portfolio interests, it is recommended that the number of calculation methods for FIFs be reduced. In particular, it is recommended that the ‘accounting profits’ and current ‘branch equivalent’ methods be removed. Reducing the choice of attribution methods available to FIF interests would simplify the tax legislation and reduce compliance costs associated with choosing an attribution method and performing the complex calculations associated with accounting profits and branch equivalent methods.

34. The proposal that PIEs apply the same tax rules to their non-portfolio investments in foreign companies as they apply to portfolio investments will reduce compliance costs faced by PIEs as they will be able to use the same calculation method for all of their foreign investments.

35. The proposal to revalue foreign shares inherited prior to October 2005 will impose some minor compliance costs on a very small number of taxpayers. These taxpayers will have to calculate the market value of these shares and may also need to apply the FIF rules to the shares if they have more than $50,000 of foreign shares.

Impact on administrative costs

36. The reform package proposed will require changes to Inland Revenue’s systems and processes. The changes will have implementation costs for Inland Revenue of $515,000 (capital) and $316,000 (operating) in 2010/11. There will be ongoing operating costs of $105,000 per year (operating).

CONSULTATION

37. An officials’ issues paper was released in March 2010 to consult on the proposed changes. The issues paper discussed the options outlined above, as well as other design issues. It suggested that investors with FIF interests of 20% or more would be able to choose to apply the new CFC rules (the active business test and active income exemption) or alternatively use the rules that were developed for portfolio FIFs (e.g. the fair dividend rate method). It asked for feedback on these and other potential options.

38. Nineteen submissions were received from a range of accounting and legal firms and businesses with offshore operations.

39. Some submitters suggested that the non-portfolio FIF rules be replaced with an anti-avoidance rule. We do not recommend this, as it would remove New Zealand tax on FIF income without regard to whether it was earned in the course of an active business or was simply profit that had been stripped out of New Zealand. It could create opportunities to reduce New Zealand tax, by shifting passive income into countries, entities or transactions that are not comparatively taxed offshore. We do not consider it possible to design a narrow anti-avoidance rule that would provide adequate protection against the possible tax minimisation strategies. Even in the event that a workable anti-avoidance rule could be developed, it is likely that it would introduce an unwanted degree of uncertainty into decision-making. A much more preferable approach is to attribute passive income.

40. Other submissions raised concerns that the proposal would deny access to the active income exemption to investors who were actively involved in the foreign company, either because the investor had a smaller shareholding, or because the investor had limited access to unconsolidated financial information. In response to these concerns, several changes have been made to the model to enable more investors to use the active income exemption.

41. Submissions pointed out that it may be easier for some investors to access consolidated accounting information for an entire group than to access information for each separate company. In response to this, it is recommended that investors be able to use consolidated accounting information to apply the active business test to a chain of related FIFs (including when the FIFs are in different jurisdictions).

42. Some submitters presented examples where investors with 10% to 20% holdings had board representation, direct input into management decisions and exchanged knowledge and skills with the investee company. In response to this, the ownership threshold for applying the active income exemption in the model was reduced from 20% to 10%.

43. Submissions generally supported the proposal that non-portfolio investors should be able to elect to use the portfolio FIF rules as an alternative to applying the active income exemption. These rules allow investors to use the fair dividend rate method (that taxes an amount based on an assumed 5% return). If the investor is an individual or family trust and the actual rate of return is less than 5%, there is a concession to reduce the 5% rate to the actual rate (if the actual return is a loss, a nil rate is used).

44. Some submissions opposed the proposal to repeal the branch equivalent and accounting profit methods. Retaining these methods alongside an active income exemption would lead to significant complexity (such as rules to adjust losses and foreign tax credits when an investor moves into the active income exemption). There would be little corresponding benefit, given that most investors with sufficient information to apply a branch equivalent method would be able to use the active income exemption. Also, we note that the accounting profits method is not currently used by many investors.

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

45. We recommend that the active income exemption be extented to substantial interests in foreign companies that are not controlled by New Zealanders (FIFs). The proposal will reduce tax and compliance costs on many offshore investments, but it is noted that it will also increase compliance costs on some.

46. The estimated fiscal cost of the active business exemption ($10m per annum), is indicative of the reduction in tax payable for New Zealand businesses with 10% or greater interests in FIFs.

47. Compliance costs for New Zealand investors with a 10% or greater interest in FIFs outside the eight grey list countries will be reduced, as long as those FIFs are mainly engaged in active business and the investor has access to sufficient information to apply the active business test.

48. New Zealand residents with a 10% or greater interest in FIFs in grey list countries, other than Australia, will experience an increase in compliance costs, because to access the exemption they would need to obtain information to apply the active business test and, in cases where they cannot apply or pass the active business test, calculate an amount of income tax to pay on the FIF’s income.

IMPLEMENTATION

49. An active income exemption for substantial interests in FIFs could be implemented in a tax bill scheduled for introduction in October 2010.

50. The main implementation risk is that the reforms will be delayed. Investors who expected to benefit from the active income exemption would have to wait an additional year until their tax and compliance costs are reduced.

51. Other implementation risks are reduced by basing the extended exemption on the earlier active income exemption that has been implemented for CFCs. This would reduce the overall complexity of the international tax rules and so make the exemption easier for companies and advisors to understand and operate.

52. As with the earlier CFC changes, a special report, Tax Information Bulletin or other guidance material will be published to provide taxpayers with information on the new rules.

MONITORING, EVALUATION AND REVIEW

53. Practical and remedial issues will be identified by tax practitioners and the operational arm of Inland Revenue, and then communicated to the relevant Inland Revenue policy official. Any necessary corrections or improvements can then be included in subsequent tax bills. In addition to this, officials will monitor international tax reforms in other countries in order to evaluate the competitiveness and integrity of New Zealand’s rules against the rules that operate in other countries.