Chapter 7 – Proposed new transfer-pricing and source rules

7.1 Introduction

7.2 The proposed new transfer-pricing rules

7.3 Integration with the rest of the Act

7.4 Improved source rules

7.5 Other possible changes to the source rules to be considered

7.6 Effective date

Summary

These reforms are aimed at improving the measurement of income by source and deterring taxpayers from manipulating transaction prices to decrease their taxes.

The proposed transfer-pricing rules will apply to:

- cross-border non-arm’s-length transactions that deplete New Zealand’s tax base;

- domestic arrangements that are part of a broader agreement involving non-residents;

- individuals and companies.

To further the Government’s objective of minimising compliance costs, it is proposed at this stage to:

- require taxpayers to make only a reasonable estimate of an arm’s-length price;

- include a presumption that unrelated parties transact at arm’s-length prices;

- allow the comparable uncontrolled price method as a safe-harbour if taxpayers can apply that measure.

A binding statement will be made on approved transfer-pricing methodologies, requiring:

- use of the best method (outside the proposed safe-harbour); and

- reasonable accuracy.

To achieve integration with the rest of the Act:

- advanced pricing agreements will be available within the binding rulings process;

- self-assessment will apply;

- limited provision will be available for downward adjustments;

- the normal disputes resolution process will apply; and

- explicit apportionment rules will apply for income that is not sourced exclusively in New Zealand.

Detailed rules for apportioning cross-border income and expenditure that are consistent with the proposed transfer pricing regime are proposed.

Parallel with the re-write of the Act, the Government will consider apportionment rules for joint costs, foreign-sourced income and income without an explicit New Zealand source and clarification of the use of the net and gross concepts.

7.1 Introduction

This Chapter outlines proposals to introduce a new transfer-pricing regime and explicit apportionment rules for income that is not exclusively New Zealand-sourced.

7.2 The proposed new transfer-pricing rules

7.2.1 Objectives

The objectives of the proposed new transfer-pricing rules and improved source rules are to:

- improve the measurement of both the net New Zealand-sourced income of non-resident investors in New Zealand and the net foreign-sourced income of residents;

- deter taxpayers from attempting to decrease their New Zealand tax liabilities by manipulating the level of income they claim to be deriving from New Zealand and foreign sources; and

- to achieve these objectives in a manner consistent with the Government’s policy of minimising compliance costs.

To achieve these objectives, the Government proposes to repeal the existing transfer-pricing rules in s.22 of the Act and replace them with a new set of rules. Explicit apportionment rules would also be introduced during the current process for income that is not deemed to be exclusively New Zealand-sourced.

7.2.2 Scope of the proposed transfer-pricing rules

The proposed transfer-pricing regime is intended to be narrowly-focused, while protecting the tax base by being difficult to circumvent. It is therefore proposed to restrict the regime to cross-border transactions which are not at arm’s-length and which deplete the New Zealand tax base.

The regime would not affect wholly domestic transactions nor ordinary cross-border transactions conducted on arm’s-length terms.

The coverage of the regime will be considered carefully in the consultative process.

7.2.3 Only cross-border transactions covered

The requirement to use arm’s-length prices would be restricted to cross-border transactions. It is only in such transactions that the source of income can be transferred out of the New Zealand tax base.

The regime would apply where a cross-border transaction is not on arm’s-length terms. The requirement to report income using arm’s-length prices would therefore apply to transactions between:

- a New Zealand resident company and a non-resident company;

- two non-resident companies when at least one of those companies is taxable in New Zealand (to the extent of its New Zealand operations);

- a New Zealand company and a controlled foreign company; and

- two controlled foreign companies resident in different countries.

7.2.4 Restricted to where the New Zealand tax base could be depleted

The requirement to use arm’s-length prices should be restricted to cross-border transactions in which a New Zealand taxpayer depletes the New Zealand tax base by:

- supplying goods or services for inadequate consideration; or

- receiving goods or services for excessive consideration.

For example, if a New Zealand subsidiary purchases trading stock from its offshore parent for excessive consideration, the cost of sales of the New Zealand subsidiary is inflated and profit and taxable New Zealand income is depressed. On the other hand, where the New Zealand subsidiary receives goods or services for a lower-than-market price from its parent, the New Zealand taxable income of the subsidiary is augmented. There is no policy reason for New Zealand to have rules preventing the latter.

7.2.5 Application to branches

The arm’s-length requirement should also apply to the rules apportioning income between branches and parent companies. Because they are not inter-entity transactions, such apportionments would not fall within any legal transactional definition. An arm’s-length rule must therefore apply to deemed transactions between:

- a New Zealand branch of a non-resident company and its head office, or other branches or subsidiaries offshore;

- a resident company and its branch or subsidiary offshore; and

- the offshore branches of two resident companies where those offshore branches are in different countries.

This objective seems to be best achieved by deeming transactions to occur between branches and parents and then applying an arm’s-length standard to:

- the gross value of goods and services supplied by the parent company to its branch (that is, the proportion of gross revenue of the company attributable to the activities of its branch); and

- the gross value of goods and services acquired by the branch from its parent company (that is, the proportion of gross expenditure of the company that is attributable to the gross income generated by the activities of the branch).

7.2.6 The need to apply the arm’s-length standard to arrangements that have a character similar to that of cross-border transactions.

As in Australia, it seems necessary to broaden the term cross-border transactions to cover arrangements that have a character similar to that of cross-border transactions.

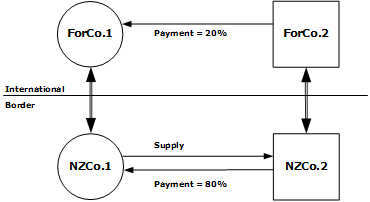

For example, while the rules would not, in general, apply to transactions between two resident taxpayers, it seems necessary for them to apply if the transactions are part of a broader agreement involving non-residents. A stylised example of such a transaction is illustrated below. It has been adapted from an Australian Tax Office ruling:[15]

(Full size | SVG source)

In this example, two unassociated company groups comprising NZCo.1 and ForCo.1 in one group and NZCo.2 and ForCo.2 in the other group, have agreed that NZCo.1 will receive 80% of the arm’s-length consideration from NZCo.2 in respect of the supply of property in New Zealand. NZCo.1’s offshore associate, ForCo.1, will receive the balance of 20% of the arm’s-length consideration from ForCo.2. While, at first glance, the transaction between the two New Zealand companies appears to be wholly domestic, the transactions represent a transfer of New Zealand-sourced income from NZCo.1 to ForCo.1. Applying the transfer-pricing rules in circumstances like these seems to be necessary to protect the New Zealand tax base.

7.2.7 Application to non-related party transactions

At this stage, it is not proposed that the transfer-pricing regime would require any control or other specific relationship between the parties to a transaction. Instead, a general obligation that all cross-border transactions be at arm’s-length prices is proposed.

Narrowing the regime to related party transactions would reduce uncertainty and compliance costs, particularly in day-to-day cross-border transactions. This would be consistent with the commercial reality that arm’s-length parties normally conduct transactions at arm’s-length prices.

However, when the Australians designed their transfer-pricing rules, they concluded that restricting them to related party transactions would enable people to circumvent them. Instead, they applied the rules to all transactions not conducted at arm’s-length. In determining whether a transaction is at arm’s-length, regard must be had to “any connection between any two or more of the parties to the agreement or to any other relevant circumstances.”[16]

A recent ruling of the Australian Tax Office (ATO) shows that a primary concern was the tax avoidance that would occur if the transfer-pricing rules depended on the existence of control or share ownership.[17] The ruling, (and other ATO transfer-pricing commentaries) refers to a number of examples of this type of avoidance. For example:

“[Consider] a deal between a company in Australia that is a member of one group with a company overseas that is a member of another, quite unrelated group. The particular transaction could be one that results in the company in Australia receiving less for its exports than the relevant price on the open market. Why, it might be asked, should a company here do that. The answer could be that there are other, completely offshore, deals between members of the two company groups that, in one way or another, redress for each group as a whole the income imbalance resulting from the reduced export price to the company in Australia. There might, for example, be such an offshore agreement not to compete in a particular market.

Whatever might be said about the arm’s-length nature of the set of deals between each of the two groups considered as a whole, the export transaction itself is not one carried out at arm’s-length and [transfer-pricing rules] are there to redress the revenue imbalance for Australia that would otherwise exist.”

This suggests that while a transfer-pricing regime restricted to related party transactions can increase certainty, there is a potential cost to its integrity. Alternatively, it could involve complex and detailed anti-avoidance rules.

New Zealand could adopt wording similar to that of the equivalent Australian legislation. However, this seems to do little to narrow the regime, while at the same time creating uncertainty about what is a “relevant circumstance” or “any connection”.

Another way of narrowing the scope of the regime (the method favoured by Government) would be to incorporate a presumption that non-related parties have transacted at arm’s-length unless there is any connection or relevant circumstance to suggest otherwise. This would put the onus on the Inland Revenue Department to demonstrate that transactions between non-related parties were not conducted on arm’s-length terms before the transfer-pricing rules could be invoked.

At this stage, it is proposed that subject to the presumption, all cross-border transactions be valued at arm’s-length prices. In the consultative process, consideration will be given to whether the regime can be more closely targeted without raising the concerns noted by the Australian authorities.

7.2.8 Application to individuals, trusts and partnerships

Transfer-pricing rules would have to apply to individuals on the same basis as they would apply to companies.

For the purpose of determining whether a transaction involving a trust is cross-border, a trust that would be a qualifying trust if it made a distribution (on the last day of its income year) should be treated as resident in New Zealand; any other trust should be treated as non-resident.

In the case of partnerships, the transaction should be regarded as cross-border if it would fall within that definition had it been with any member of the partnership. For example, the rules would be invoked if a partnership containing one non-resident member conducted a transaction with a resident. Where the transaction is not at an arm’s-length price and the source of income is moved offshore, total New Zealand-sourced partnership income would be adjusted upwards. This should affect only non-resident partners, since resident partners are taxable on worldwide income. The adjustment should change the composition, but not the amount, of the resident partner’s assessable income.

7.2.9 De minimus rules

In general, overseas transfer-pricing rules avoid de minimus rules, which seem to be seen as arbitrary exemptions from what should be a general requirement that taxpayers transact at arm’s-length. Arguably, the unsophisticated taxpayer at whom de minimus rules are aimed is unlikely to engage in significant transfer-pricing activity.

Moreover, while de minimus exemptions can reduce compliance costs, they can also increase uncertainty. Compliance concerns may be better met by applying a reasonably flexible approach to calculating the required arm’s-length prices. Suggestions are given below for a comparable uncontrolled price safe-harbour rule and a reasonable estimate rule.

7.2.10 Determinations of arm’s-length transfer-prices

Taxpayers will need explicit guidance on the methodologies to use in determining arm’s-length transfer-prices.

To assist them in this process, the Government proposes to issue a binding public statement on the question. This statement could be made in a number of different forms, including regulations or determinations issued by the Commissioner of Inland Revenue. Submissions are sought on the most appropriate form for the binding statement.

7.2.11 Methods of determining the arm’s-length transfer-price

Where feasible, the arm’s-length price would be set using the comparable uncontrolled price method. Under this method, the arm’s-length price would be set by reference to similar transactions in which adequate consideration was provided for the goods and services transferred, with adjustments for any minor differences in the nature of the transactions. Using the comparable uncontrolled price would, in effect, provide a safe-harbour rule for taxpayers. Taxpayers would have the assurance that, if they used this method, Inland Revenue would not impose a different methodology.

If a comparable uncontrolled price could not be identified, an appropriate proxy method for estimating the arm’s-length price would be applied.

Possible proxies include:

7.2.11.1 The resale price method

This method could be applied where a New Zealand taxpayer (reseller) purchases goods or services from a related offshore supplier (supplier) which are then on-sold to an unrelated customer. To determine the transfer price for the controlled transaction (supplier to reseller), an arm’s-length gross profit margin plus any relevant expenses is deducted from the price paid in the uncontrolled transaction (reseller to unrelated customer). The arm’s-length gross profit margin would be obtained by reference to comparable uncontrolled sales of similar products.

7.2.11.2 The cost plus method

This method could be applied where a New Zealand taxpayer supplies goods or services to a related offshore party. The transfer price for this controlled transaction is determined by adding an arm’s-length gross profit margin to the costs incurred by the New Zealand taxpayer in supplying the goods or services to the related offshore party The arm’s-length gross profit margin would be determined by reference to comparable uncontrolled profit margins in similar activities.

7.2.11.3 The comparable profits method

Under this method, it is presumed that the taxpayer earns a profit similar to comparable uncontrolled profits of similar persons in similar industries, measured as a return on assets, operating assets or equity; or as ratios of profit to sales, or some other financial ratio; or by some other appropriate measure. This method is most similar to s.22 of the Act.

7.2.11.4 The profit split method

Under this method, the profit of a group of persons engaging in a common activity is apportioned among the members of the group, using an apportionment system that would be agreed upon by unrelated persons acting at arm’s-length. For example, the profit might be distributed in proportion to the capital contributed by each member, taking into account differing bargaining powers such as the ability to contribute intangibles or some other unique asset.

7.2.12 Application of the best method

It is proposed that if taxpayers cannot use the comparable uncontrolled price, they should use the method that provides the most accurate and practical measure of the arm’s-length price.

This would give taxpayers and the Inland Revenue Department maximum flexibility in arriving at methods that best suit the very different circumstances in which arm’s-length prices are required. For example, profit-based methods could be applied in circumstances where they yield a more accurate and practicable method of determining net New Zealand-sourced income than transactions-based methods would.

The approach outlined in the previous paragraph is similar to the “best method” rule used for the US transfer-pricing rules. The US regulations for determining the most reliable arm’s-length method outline a range of factors that must be considered, including:

- the degree of comparability between the uncontrolled transactions used for comparison and the controlled transactions of the taxpayer;

- the completeness and accuracy of the underlying data;

- the reliability of the assumptions used; and

- the sensitivity of the results to possible deficiencies in the data and assumptions.

It seems appropriate to apply the same guidelines in New Zealand.

Generally, taxpayers would be expected to follow the same methodology for similar transactions and from one year to the next, unless the best-method rule called for a different one. This might occur because of a change in circumstances or the available data, or because a different method gave more accurate results.

Taxpayers will be able to agree with the Department in advance on the method that best suits their circumstances. One option would be to obtain either a binding or non-binding ruling. Obtaining such an upfront agreement can reduce uncertainties.

7.2.13 Accuracy requirement

Arm’s-length price calculations are merely estimates of what the price would have been if the transaction had been conducted between arm’s-length parties. Because of this, there is always room for disagreement about the exact arm’s-length price that the taxpayer should adopt. This can create uncertainty for taxpayers and conflict with revenue authorities.

There are two ways to reduce this problem.

The first is the United States approach, which allows a range of arm’s-length prices; the extent of the range is determined by the accuracy of the statistical data used. Under this approach, the taxpayer can use an actual transfer-price if it falls within the range. If the data-source used for the range is highly accurate (for example, comparable uncontrolled prices for the sales of the same products on similar terms), the acceptable range would be the entire range of arm’s-length prices. If the data source is less accurate (for example, sales of similar, but not the same, products) the arm’s-length range may be only a portion of the entire range of arm’s-length prices.

An alternative is to require taxpayers merely to make a reasonable estimate of an arm’s-length price. If the Inland Revenue Department challenges that price, it would have to establish, as a threshold issue, that the taxpayer’s estimate was unreasonable.

The approach adopted may depend on the overall structure of the regime. For example, as noted above, a reasonable estimate rule could be adopted instead of de minimus exemptions. The current proposal is for a reasonable estimate rule, but the Government will consider submissions on this.

7.3 Integration with the rest of the Act

7.3.1 Binding rulings and advance pricing agreements

It is proposed to incorporate provisions for issuing advanced pricing agreements under the binding rulings process, in order to:

- provide certainty to taxpayers who engage in transactions that are potentially subject to the new transfer-pricing rules, preventing possibly lengthy and costly transfer-price investigations later. An up-front investigation, with the taxpayer’s co-operation, is likely to be easier than an adversarial ex-post investigation. In addition, if a multilateral agreement is used, the other countries’ tax authorities may be able to help determine the arm’s-length price; and

- reduce international disputes over source of income. It is important to note that countries that did not participate would not be bound, so such disputes could not be eliminated altogether.

To obtain an advance pricing agreement, taxpayers would have to disclose all relevant information. As with any other binding ruling, the agreement would bind the Commissioner of Inland Revenue only if this were done.

7.3.2 Self-assessment process

In order to be properly integrated into the way the modern New Zealand income tax system operates, the transfer-pricing regime has to operate within a self-assessment system. This means that taxpayers must use the transfer-pricing methodologies to determine their taxable income when engaging in transactions subject to the regime. The Commissioner of Inland Revenue should then be able to apply normal re-assessment procedures if he or she determines that the taxpayer did not comply with the regime. When reassessing taxpayers, the Commissioner would have to comply with the guidelines issued on the methods that taxpayers are expected to employ for calculating arm’s-length prices.

7.3.3 Provision for downward adjustments

It is proposed that, in general, the transfer-pricing methodologies will supersede the actual terms of the transaction only where this would increase the taxpayer’s taxable income, or reduce a loss. In certain circumstances, however, the new rules could allow taxpayers to adjust their actual transaction prices in a manner that would reduce their New Zealand taxable income. An example is where a New Zealand parent charges a subsidiary CFC an excess price for goods. If CFC income must be returned based on the lower arm’s-length cost of its purchases, there is an argument that the parent should return income using the same arm’s-length price.

A downward adjustment to taxable income may be appropriate when:

- it is to offset an adjustment to the other party to the transaction, when both parties are taxable by New Zealand; or

- the adjustment is required to comply with a multilateral competent authority adjustment.

Any provision for such downward adjustments must fit within a self-assessment system and be administratively manageable. A process that enabled taxpayers to dispute the outcome of a specific transfer-pricing adjustment by requesting a series of compensating adjustments to other, unrelated, transactions would probably be unworkable.

The proposed compromise is that taxpayers should be able to make downward adjustments that are the direct consequence of an upward adjustment to the same, or another, taxpayer. This provision must be subject to sufficient information being provided to the Inland Revenue Department - including identification of the downward adjustment sought and the other adjustment to which it directly relates. Provision would have to be made for later reassessments when a downward adjustment is sought following a reassessment including an upward adjustment, or an alteration to such an adjustment.

7.3.4 Dispute resolution processes

Unilateral transfer-price issues would proceed on the same basis as domestic tax disputes. For tax purposes, the taxpayer would report cross-border transactions at arm’s-length terms on a self-assessment basis and the Commissioner could investigate transfer-price issues in an audit. Following re-assessment, the taxpayer could go through the objection process and, if necessary, dispute the tax liability through the court system.

If a transfer-price dispute involved allocation of income with a DTA partner, the taxpayer could invoke the competent authority provision of a treaty. In this case, the Inland Revenue Department would discuss the transfer-price issue with the competent authority of the other country and an agreement would be made among the competent authorities, as provided in the DTA.

7.3.5 Penalties

The new transfer-pricing rules do not seem to require any special penalty provisions. If a taxpayer failed to comply with the rules, the standard hierarchy of penalties, as finally determined following the completion of the Penalties and Compliance Review relating to taxpayer culpability, would apply - that is, negligence, lack of a reasonably arguable position and so on. It should be stressed that the Government has yet to make final decisions on the Penalties and Compliance Review.

7.3.6 Reporting and record keeping requirements

Taxpayers already report differences between their normal accounts and their accounts for tax purposes. For administrative purposes, there will have to be a specific requirement that where a taxpayer uses an arm’s-length price for a particular transaction instead of the actual price paid, that transaction will be reported.

On a more general level, it is proposed that disclosure will be required whenever taxpayers use DTA provisions to override other specific provisions of the Income Tax Act. This new provision will apply to the Act generally, not just to the new transfer-pricing rules.

Taxpayers would be required to retain records supporting their cross-border transaction decisions for seven years, in line with the practice for all records relating to determining tax liabilities.

No other special record-keeping rules regarding transfer-pricing are proposed.

7.3.7 Structure of the legislation

It is proposed that the legislation be structured like that of Australia. Under this approach, the legislation itself would require only that transactions subject to the regime be reported at arm’s-length. The legislation would also define arm’s-length in a general way, using terminology similar to that used in OECD reports.

Guidance in determining arm’s-length prices would be provided in regulations or determinations. The alternative, which the Government does not favour, would be to include the required methodologies in the legislation itself.

As already noted, it is anticipated that the regulations or determinations describing the methodologies outlined above would be published before the regime came into effect. Supplementary regulations or determinations could be published later, refining these methodologies or providing new ones reflecting experience with the regime.

It is proposed that the transfer-pricing rules be superior to all other Income Tax Act sections for the purpose of determining the price at which transactions occur. This means that the other sections, including s.99, would apply only after application of the transfer-pricing rules. However, it would always be open to the Commissioner of Inland Revenue to adjust transfer-prices under s.99 if that were necessary to restructure a tax avoidance arrangement. More generally, an appropriately calculated arm’s-length price would be deemed, for all purposes of the Act, to have been the price at which the transaction occurred with respect to the taxpayer or taxpayers for which the arm’s-length calculation was made.

The existing anti-abusive transfer-pricing rules outlined in s.22 of the Act would be replaced by the proposed new rules.

The transfer-pricing rules would work in conjunction with the deemed dividend rules contained in s.4. In this instance, the arm’s-length price would be used to determine the market value. For example, if a New Zealand company purchased inventory from its parent at more than the arm’s-length price, the transfer-pricing rules would deem the purchase price to be the arm’s-length price, thereby reducing deductions. In addition, s.4 would deem the amount paid in excess of the arm’s-length price to be a dividend to the parent. The combined effect of transfer-pricing and deemed dividend rules would be to increase the company’s profits from which a higher-than-declared dividend was paid.

If the taxpayer originally reported income using an arm’s-length price, the adverse effect of such a rule should be mitigated by the extension of the FITC regime, because any dividends arising should, generally, be covered by imputation credits.

7.4 Improved source rules

7.4.1 Proposed apportionment rules

To measure their net New Zealand-sourced income and to comply with the proposed transfer-pricing rules, taxpayers need clear rules for apportioning, between countries, income that has more than one source (where such apportionment is allowed).

As discussed in Chapter 4, s.245 (the general apportionment provision) provides little guidance on how such an apportionment process should be carried out. Clearer apportionment guidelines would help taxpayers to comply with the requirement under s.245 to apportion, between countries, income that is not deemed to be exclusively New Zealand-sourced - for example, business profits derived by a non-resident with a branch in New Zealand.

It is proposed that the Inland Revenue Department remedy this position by providing more detailed cross-border apportionment guidelines which are consistent with the transfer pricing rules outlined in this document.

These rules could be set out in regulations issued in accordance with s.245 of the Act. Alternatively, the Commissioner of Inland Revenue could issue a policy statement (for example, a Technical Information Bulletin) clarifying the apportionment rules considered by the Commissioner to be “just and reasonable” for the purposes of s.245. Submissions are invited on which of these alternative approaches would be preferable. Draft guidelines will be released at a later date for consultation.

The gross income apportionment methodologies would outline common measures that taxpayers could use to apportion forms of gross income between countries. This would give taxpayers a clear indication of how to apportion, between countries, income that is not deemed to be exclusively New Zealand-sourced. In addition, it would ensure consistency in apportioning particular types of gross income.

7.4.2 Apportionment of joint costs

As discussed in Chapter 4, a specific apportionment problem arises with expenditure which has been incurred jointly in deriving New Zealand-sourced and foreign-sourced income. Possible apportionment rules to apply to such joint costs were recommended by the Valabh Committee in their report on “Tax Accounting Issues”. As a separate exercise the Government will be considering those recommendations.

Specifically, during consultations on this issue, consideration will be given to:

- introducing more targeted apportionment rules for non-interest joint expenditure (that is, expenditure incurred in producing assessable and non-assessable benefits);

- basing the apportionment of non-interest joint expenditure on a common measure that fairly and reasonably results in an objective allocation of the joint expenditure between the benefits produced by that expenditure; and

- where it is not practicable to use a common measure, basing the apportionment on the dominant purpose for which the joint expenditure was incurred.

Such apportionment rules for joint expenditure could be used to apportion joint expenditure not only between gross income derived from different countries, but also between activities that produce both taxable and non-taxable benefits.

7.5 Other possible changes to the source rules to be considered

In addition to apportionment issues, Chapter 4 also identified a number of other problems with the existing source rules. These included structural problems arising from uncertainty over whether the rules relate to gross or net income and the absence of general definitions of New Zealand-sourced and foreign-sourced income. As a result, in parallel with the re-write of the Income Tax Act, the Government also intends to consider possible amendments to the source rules in the Act, to:

- implement separate definitions of New Zealand-sourced income, foreign-sourced income and income that is not exclusively New Zealand-sourced; and

- clarify the use of the net and gross concepts in the definitions of New Zealand-sourced and foreign-sourced income.

7.6 Effective date

It is proposed that the transfer-pricing legislation be introduced by the middle of 1995. Provided that this timetable is met, the transfer-pricing regime and the guidelines would therefore be effective from the start of the 1996-97 income year.