Chapter 2 – Policy making considerations

2.1 Introduction

2.2 Outline of the chapter

2.3 The broad aim of international tax policy

2.4 Influences on investment

2.5 The source of capital - domestic or foreign

2.6 The impact of taxes

2.7 The problem of double taxation

2.8 The role of tax treaties and tax administration considerations

2.9 The relationship between domestic and international tax

2.10 Foreign tax credits received by non-residents

2.11 Other important considerations

2.12 Conclusion

A general discussion on the broad framework for international tax

2.1 Introduction

Previous consultations on international tax reform have tended to focus directly on the proposed measures themselves. Although “Taxing Income across International Borders - A Policy Framework” introduced a comprehensive discussion of the rationale and issues underlying international tax policy, there was little feedback on that document at the time that it was published (July 1991). This lack of focus in the past has made it difficult to explain the underlying rationale for the Government’s international tax proposals.

To fill this gap, the Government has been working through the issues involved in the international tax regime identifying those factors that must be considered if the Government is to meet its economic and tax policy objectives. This will provide the context for discussion on international tax policy. In the process of developing this discussion document, the Government has undertaken preliminary consultations with overseas experts and members of the business community.

This chapter highlights these issues, many of which are based in economic theory and very technical in nature. To make the points while keeping the exposition as straightforward as possible, the economic aspects of the discussion simplify many of the real-world factors that influence business investment decisions.

It has already been pointed out that the Government, in determining its tax policy, endeavours to meet many objectives, some of which do not fit neatly with each other. Greater accuracy, for example, can often only be achieved at the cost of greater complexity and vice versa.

The design of an international tax regime involves many judgments about the economic effects of taxes, and the numerous trade-offs between the economic effects and the various practical issues. The following analysis focuses largely on the economic effects of tax policy rather than the related practical issues. As such, it is an illustrative guide to the economics of international tax rather than a definitive statement of the tax policy framework that must be rigorously followed.

2.2 Outline of the chapter

This chapter first discusses economic considerations. It adopts a step-by-step approach to illustrate how the many important judgments fit into the analysis, and how they affect the design of the international tax regime. This approach should make it easy for readers to pinpoint any particular areas of concern about the economic analysis and the judgments made. Being able to identify their key concerns should enable parties to engage in a process of consultation on international tax which will be more constructive than in the past.

The economic discussion starts by canvassing the aims of international tax policy. It then looks at the factors, other than tax, that influence investment decisions. Analysing such influences is important, because an ideal tax system is one in which tax plays as small a role as possible in investment decision-making.

The discussion then considers the ways in which New Zealand taxes can influence the investment decisions of New Zealanders investing here and overseas, and of non-residents who are considering investing in New Zealand. This discussion includes comments on the influence of taxes imposed by other countries on the New Zealand Government’s tax policy.

Finally, the discussion outlines other important considerations that the Government must take into account when setting international tax policy, including the need to protect the domestic tax base, the need to reduce the costs of complying with and administering the tax system, and the desirability of sustainable policy.

2.3 The broad aim of international tax policy

2.3.1 Introduction

Because New Zealand is an open economy, New Zealanders are free to invest either in New Zealand or offshore. Likewise, foreigners can invest in New Zealand or elsewhere.

For the purposes of this discussion, investment activity is divided into three separate forms. They are:

- investment undertaken outside New Zealand by New Zealanders. This sort of investment uses exported capital;

- investment undertaken in New Zealand by non-residents. This uses imported capital; and

- investment undertaken in New Zealand by New Zealanders. This uses domestic capital.

Although a discussion of domestic investment may seem out of place in a document dealing with international tax, taxes on cross-border income flows in fact have a marked impact on investment decisions, and the way that all three forms of investment interact is a key tax policy consideration.

2.3.2 Supporting efficient use of New Zealand’s resources

A fundamental aim of the Government’s policy will always be, consistent with meeting other policy objectives, to ensure that, whatever the location of investment or the source of finance, all investment decisions make the most efficient use of New Zealand’s resources. Policy that achieves this objective will make the greatest possible contribution to economic growth and consequentially improving living standards for all New Zealanders.

Investors use relative rates of return as a guide to choosing the most productive of alternative investments, both in New Zealand and overseas. For example, if relative rates of return are higher overseas than they are in New Zealand, the incentive on non-residents especially, but NZ residents as well, will be to invest offshore as opposed to in New Zealand.

It has to be taken as read that an unavoidable consequence of gathering government revenue through taxes is to reduce the actual direct return the investor achieves on the investment. To promote investment that benefits New Zealand, therefore, it is important to ensure the tax system does not have adverse effects on the relative rates of return available from onshore as opposed to offshore investments.

Less obvious, however, are the ways the tax system can affect patterns of investment. Deficiencies in the tax regime that result in different rates of New Zealand tax being applied to different types of investments will alter the relative rates of return investors can derive from those investments. This imposes a “deadweight cost” on the economy by potentially supporting inefficient patterns of investment.

If the international tax regime is to play its part in encouraging the efficient use of New Zealand’s resources, the Government must aim for a regime that does not distort the relative rates of return from alternative investments both in New Zealand and offshore. When relative rates of return are not distorted by tax, investors will concentrate on those activities that make the most efficient use of New Zealand’s resources, rather than those investments that take advantage of deficiencies in the tax system.

There is also an inescapable link between the world and the domestic rate of return on capital. If the return on domestic investment exceeds the cost of imported capital, then New Zealand can gain by increasing the level of investment financed by imported capital. Conversely, if the return on domestic capital is lower than the costs of foreign capital, then New Zealand loses money by financing domestic investment with foreign capital.

Hence, New Zealanders will gain where productive investment opportunities available to them give a return at least as high as the cost of foreign capital. And likewise, New Zealand benefits from making offshore investments only if the return to New Zealand is at least as high as the returns available domestically. To do otherwise would mean that New Zealanders would be investing offshore when better opportunities are available locally.

Combining these two factors means that New Zealanders should have an incentive to invest offshore only when the returns are at least as high as the cost of imported capital.

These two factors can be summarised as follows:

FACTOR ONE: New Zealanders should continue to take up domestic investment opportunities until the return to domestic capital falls to the level of the cost of imported capital, but not below it.

FACTOR TWO: New Zealanders should continue to take up offshore investment until the return to exported capital falls to the level of the cost of imported capital, but not below it.

If the international tax regime alters the relative rates of return available in New Zealand such that either of these two conditions, or both, are not met, then New Zealand will not be making the most efficient use of its resources.

2.4 Influences on investment

Cross-border investment occurs for a variety of reasons. Tax related issues are but a part of the overall picture. The impact of these differing influences varies depending on the type of investor.

Although the reasons for investment and types of investor are myriad and complex, there are two types of investors generally considered in a broad discussion such as this. They are portfolio and direct investors.

A portfolio investor is a shareholder with a non-controlling interest in a company. The level of shareholding is generally less than 10% of a company’s shares or, alternatively, consists solely of debt instruments in a company. Usually the holdings are relatively liquid and small influences can see major changes in the content of a particular investor’s portfolio.

In New Zealand, portfolio investors have a wide range of investment options to choose from. It is safe to assume that portfolio investors will, as a key motivation, seek the highest return on the funds at their disposal. The nature and location of specific investments are less of a factor in investment decision-making for portfolio investors. The motivation for investment will include the desire to diversify portfolio risk.

Direct investors, by contrast, are investors who take a significant stake in the company in which they invest. Factors other than immediate return on capital are important determinants of direct investors’ investment decisions. These investors will tend to follow carefully the performance of the particular company concerned, and will often actively participate in the operations of the company. They will almost certainly have some influence over the affairs of a company, if not a controlling interest. Many direct investments will be wholly owned subsidiaries.

Direct investments are less liquid. They do not move out of a holding quickly or merely because the rate of return is temporarily lower than they expect. Factors such as the location of markets and production inputs, tariffs and other barriers to trade, and access to new technology and knowledge will concern direct investors. In the longer term, however, direct investors will still be influenced by the return on their investment.

The return that investors seek is an amalgamation of all the factors that influence investment.

2.5 The source of capital - domestic or foreign

The amount of capital imported into a country will be influenced by the extent to which foreign investors can switch from investments in one country to investments in other countries. The comparative rates of return available from investments between countries will be important in driving switching between countries. Obviously, political and economic stability also play a role in an investor’s decision to go into a particular country, as do a variety of other features of a particular economy.

In a small open economy like New Zealand’s, the supply of foreign capital is very sensitive to the rates of return available in New Zealand compared with rates of return available in other countries.

Further, because New Zealand is such a small part of the world capital markets, changes in the supply and demand for capital here have no discernible effect on those world market rates. It is the actions of international investors operating throughout the world’s financial markets that set the return for imported capital.

From the New Zealand business perspective, demand for foreign investment funds will depend on a number of factors, including the rates New Zealand businesses must pay for domestically sourced capital and the extent to which New Zealand firms are willing to switch from domestically sourced capital to foreign capital.

If New Zealand businesses are in a position where they can readily switch between domestically sourced and foreign-sourced capital, their demand for domestic capital will be very sensitive to the rates of return paid to foreign investors.

Although levels and sources of investment are sensitive to many factors, the implication of this process is that the more freely business investment can move, the more investment decisions will be influenced by the world rate of return required by non-resident suppliers of such capital.

2.6 The impact of taxes

2.6.1 Introduction

To understand the impact of taxes, we have to first consider what would occur were there no taxes.

Theoretically, the real cost of foreign funds equals the pre-tax return accruing to non-residents minus the portion of that pre-tax return received by New Zealand as tax revenue. For the purposes of the following discussion, assume this figure is 10%.

Consider the case in which foreign investors are able to earn 10% by lending money to a number of prospective borrowers. In this example, foreign investors are indifferent as to where they earn their money. Given these assumptions, New Zealand businesses will have to pay non-resident investors 10% after tax to attract finance. If they paid less than 10%, foreign investors would simply shift their investments to jurisdictions in which they can earn 10% after tax.

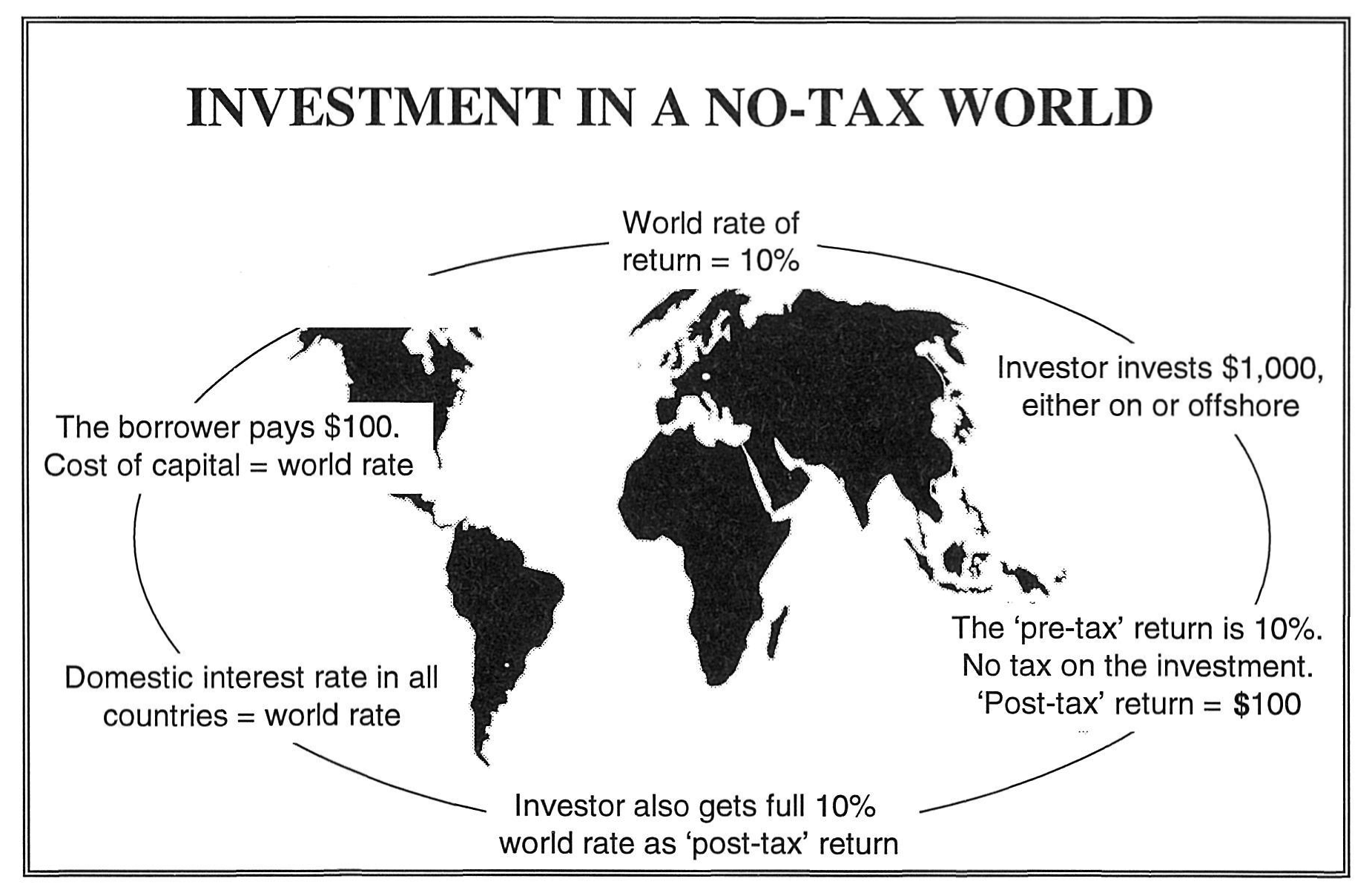

Figure 1

In this simplified model of the world, because there are no taxes, there are no tax-driven distortions to economic behaviour. Funds move freely to the highest bidder. The world rate of return applies to all investments, whether they be imported, exported or domestic capital.

2.6.2 How taxes affect investment decisions

To the extent that taxes reduce equally the return to the investor from all potential investments, then the level of investment will be affected, but not the pattern of investment. If taxes alter the relative returns from different investment opportunities, then the pattern of investment will be altered, leading potentially (as explained in the section above on efficient use of New Zealand’s resources) to a less efficient use of New Zealand’s resources.

New Zealand tax policy will alter these impacts least when investment and production choices of individuals and firms are least affected by income taxes levied by New Zealand.

There are several ways New Zealand can tax the three bases referred to in this discussion; that is imported, exported or domestic capital. New Zealand could:

- tax residents only on their domestic income

- tax residents on their world-wide income

- tax non-residents on their New Zealand-sourced income

Each of these is now considered.

a) New Zealand taxes only residents and only on their domestic income

The overall return to New Zealand equals the after-tax return to the New Zealand investor plus the tax revenue paid to the New Zealand Government. That is, the return on the investment is spread between the investor and the Government. The pre-tax return on domestic investment reflects the productivity of the investment for New Zealand.

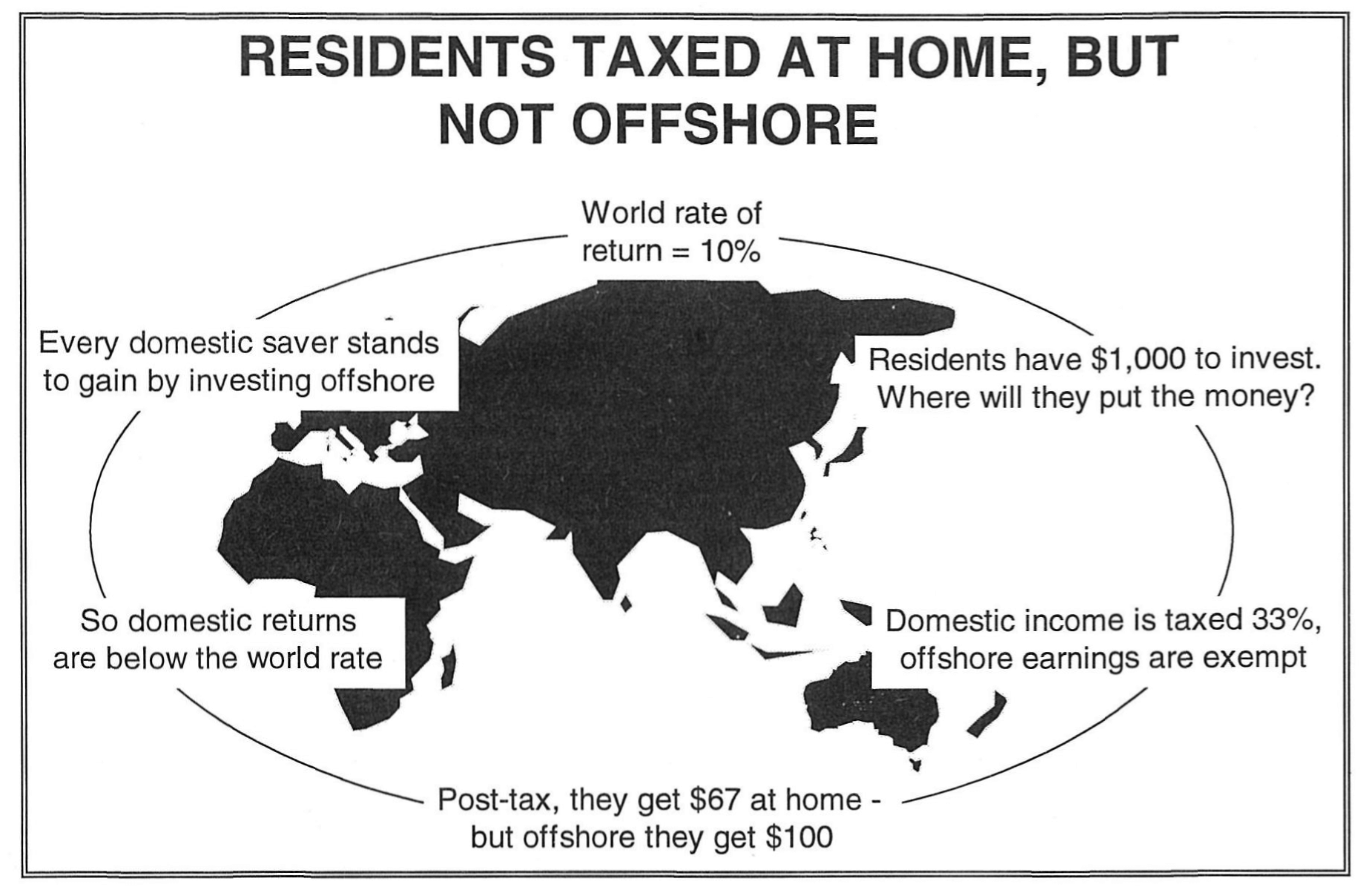

Where there are no or lower foreign taxes (assuming all else is equal), imposing New Zealand tax on residents’ domestic income, while exempting residents’ foreign-sourced income from tax, would merely drive residents to invest offshore where there are no or lower taxes. In this case, to the extent of New Zealand taxes lost because the investment is not located in New Zealand, there would be a loss to New Zealand. Consider the following example:

Suppose a resident has $1,000 to invest and that domestic income is subject to a 33% New Zealand tax rate but that offshore income is exempt from New Zealand tax. The investor can earn after-tax income of $67 at home. The residents will invest in any offshore project yielding pre-tax returns as low as $67, but only invest at home if the pre-tax return is at least $100. Thus, an exemption for offshore income encourages New Zealanders to invest in offshore projects yielding less than the 10% rate of return. A New Zealand investor could borrow from foreigners at a 10% interest rate and on-lend it to other foreigners at a 6.7% interest rate and still have the same amount of cash in hand.

Therefore, to refrain from taxing the earnings of foreign investments of New Zealanders is obviously a bad policy from New Zealand’s point of view. The following diagram explains this point. For the purposes of the diagram, we will assume there are no taxes offshore.

Figure 2

Figure 2 illustrates why it is inefficient to tax domestic investment but not exported investments. It is of course a stylised example. The extreme result is a tax system that collects no revenue, but encourages New Zealanders to hold tax-free investments offshore and non-residents to hold tax-free investments in New Zealand. Non-residents taking up the investment opportunities abandoned by residents will, however, still require the full 10% world rate of return to come to New Zealand.

b) New Zealand taxes only residents but on their world-wide income

Under this scenario, New Zealand would tax the offshore income of residents at the same rate that applies to residents’ domestic income.

This approach is referred to as the residence basis for income taxation.

Under the residence basis of taxation the after-tax return to residents from both domestic and offshore investments is reduced by the same proportional amount. As a result, New Zealand investors will choose the investment yielding the highest pre-tax return because that also yields the highest post-tax return. Offshore investment under these circumstances will occur only when the investment returns justify the investment; that is, when the after-tax return is equal to or greater than that achievable in New Zealand.

In the example above, New Zealand residents will invest offshore only when they can earn more than the $67 after-tax income available at home. If residents are subject to a 33% tax rate on both their domestic and offshore income, then they will invest only in offshore projects yielding pre-tax income equal to or greater than $100: in the absence of foreign taxes investments benefit New Zealand because: (1) the overall return for New Zealand (i.e., the pre-tax income) equals or exceeds what they could have achieved at home; and (2) the overall return exceeds the cost of foreign capital to New Zealand. The latter condition means that any cross-hauling effects benefit New Zealand.

There are, however, situations where New Zealand cannot fully tax offshore income. Both practical and inter-jurisdictional difficulties arise. For example, some international agreements New Zealand has entered into limit our ability to tax New Zealanders in other jurisdictions. In particular, double tax agreements (DTAs) New Zealand has entered into (as well as practical considerations) generally prevent New Zealand from taxing foreign companies on offshore income they derive that accrues to New Zealand residents. Moreover, if a New Zealand resident makes a direct investment in a country with which we have entered into a DTA, New Zealand tax will generally be reduced by credits for any foreign tax paid.

As a result, the effective tax rate New Zealand imposes on foreign-sourced income can be lower than the rate applied to domestic-sourced income.

c) New Zealand taxes residents only on their New Zealand-sourced income and non-residents

Applying the same rate of tax to both residents’ and non residents’ New Zealand income is referred to as the source basis for income taxation. Under the source basis taxation system, all income earned in New Zealand by both residents and non-residents would be fully taxed.

The source basis of taxation has the apparent advantage of seeming to be “fairer” than a residence basis. Under the residence basis New Zealand investors would be fully taxed on their domestic and foreign income whereas competing non-resident investors would be exempt from New Zealand tax even on New Zealand investments. However, such a conclusion loses its strength if the burden of any tax New Zealand levies on non-residents is in fact merely shifted on to New Zealand residents.

Can non-residents shift the burden of New Zealand taxes?

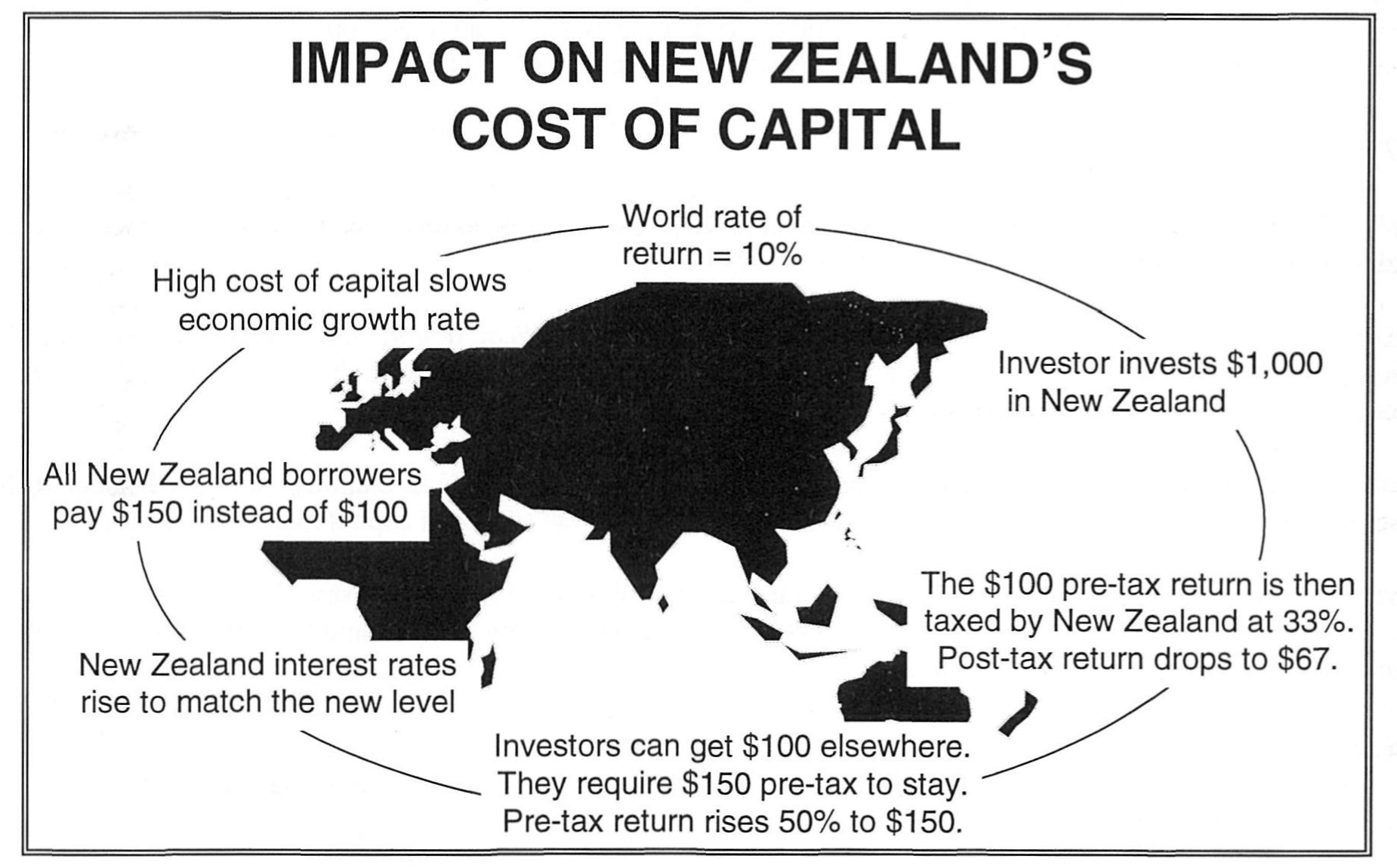

Again, the example begins with the world rate of return equal to 10% and a foreign investor having $1,000 to invest in any offshore country including New Zealand. The return is, however, taxed by New Zealand at say 33%.

Figure 3

International capital markets will endeavour to respond to the imposition of such a tax. Investors with liquid funds can either transfer their funds to a country other than New Zealand where they can earn the required 10% post-tax rate of return or demand higher returns from New Zealand to compensate for the effect of its taxes on non-residents.

Returning to the earlier example, the initial impact of New Zealand’s taxation of non-residents will be to reduce returns to non-residents from $100 pre-tax to $67 post-tax. Because investors can earn $100 elsewhere, in these circumstances they will require $150 pre-tax to continue to invest in this country. Therefore, pre-tax returns increase by 50% to $150. Because of the operation of financial markets, interest rates in New Zealand would also rise to match the new level. This means that all New Zealand borrowers must pay $150 instead of $100 to borrow $1,000 from any potential investor be they domestic or non-resident. This means that the cost of capital in New Zealand increases, slowing economic growth.

Care therefore has to be taken with the practical application of the source taxation method. To the extent that non-residents can shift the burden of New Zealand taxes back onto New Zealand businesses by covering the cost of any New Zealand taxes paid in the price they charge for the funds, taxing non-residents adds to New Zealand business costs and will not improve New Zealand’s competitiveness.

If taxing non-residents leads to a higher domestic cost of capital, New Zealand firms will need to reduce their costs, including potentially the real wages of their workers so that they can pay the higher cost of capital and remain internationally competitive in product markets.

Taxing non-residents could therefore prove self-defeating for New Zealand businesses to the extent that it merely led to a rise in the domestic cost of capital. It follows therefore that an issue for international tax policy consideration is to assess to what extent taxes on non-residents impact on the domestic cost of capital.

2.7 The problem of double taxation

In the above examples, other countries do not tax income. In practice this generally does not occur. The analysis is now extended to reflect the impacts of such taxes.

When other countries tax cross-border income, the potential for juridical double taxation arises. Juridical double taxation occurs when both the country where income is earned and the country where the investor resides tax the same income.

If there are no foreign taxes, taxing New Zealanders’ domestic income while exempting New Zealanders’ offshore income from tax will drive investment offshore (the section above on the source of capital discussed this point).

To see how foreign taxes alter this conclusion, consider the case of a world (including New Zealand) where there are no taxes. Assume a New Zealander has $1000 to invest in three countries: New Zealand and two other countries, A and B. The interest rates in each country are as follows.

CASE 1

| Country A (zero tax) |

Country B (zero tax) |

New Zealand (zero tax) |

|

| Pre-tax Return | 11% | 9% | 10% |

In this case, the New Zealander investor would invest in country A, because that is where they can earn the highest return (the investor’s choice is in bold).

Now consider what happens if Country A imposes a tax of, say, 20%, on all foreigners, including New Zealanders, investing there. The investor now earns the following rates of return:

CASE 2

| Country A (20% tax) |

Country B (zero tax) |

New Zealand (zero tax) |

|

| Returns after Foreign Tax | 8.8% | 9% | 10% |

In this case, the New Zealander would rather invest in New Zealand than in Country A or Country B.

Case 2 provides the benchmark from which to judge the imposition of taxes by New Zealand. If New Zealand had no taxes it would not try to offset the foreign tax with a subsidy to encourage New Zealanders to invest in Country A. Theoretically therefore the same result should apply when New Zealand taxes domestic and foreign-sourced income.

Now consider the case where New Zealand imposes a 33% tax rate on New Zealanders’ domestic-sourced income, while their foreign-sourced income remains untaxed.

In this case, the incentives facing the New Zealand resident investor again change. They would now prefer to invest in Country B than in either New Zealand or Country A.

CASE 3

| Country A (20% tax) |

Country B (zero tax) |

New Zealand (33% tax) |

|

| Returns after Tax | 8.8% | 9% | 6.7% |

However, from New Zealand’s point of view the investment choices made in Case 2 remain preferable: the investor should invest in New Zealand, because that is where the overall return to New Zealand is highest.

New Zealand can restore the benchmark result in Case 2 by taxing its residents’ foreign-sourced income in addition to any taxes imposed by foreign governments. If it does so, the investor faces the following returns:

CASE 4

| Country A (20% tax) (33% NZ tax) |

Country B (zero tax) (33% NZ tax) |

New Zealand (33% NZ tax) |

|

| Returns after Tax | 5.8% | 6% | 6.7% |

In practice, however, a deduction system along these lines cannot be applied. There are a number of reasons for this including the costs that such an approach would add to the New Zealand economy.

Our DTAs require New Zealand to adopt either an exemption or foreign tax credit approach. Under an exemption approach foreign-sourced income is exempt from New Zealand taxes. Whereas, under the foreign tax credit approach, New Zealand gives a credit for foreign taxes paid by its residents on their foreign-sourced income.

Further, there is a concern that other countries would strongly object to a system that would be seen by them as a deliberate effort by New Zealand to place an extra tax cost on businesses investing in their country, thus deterring investment in their economy.

In addition, as a rule those involved in business activity do not regard tax cost as the same in character as other business costs. The business proprietor has no control over taxes. Intuitively therefore in principle, the general reaction would be that it is wrong to impose a layer of New Zealand tax on top of a layer of tax already paid overseas. the deduction approach would be seen by most people as imposing an unfair tax burden on New Zealanders investing offshore.

In line with this theoretical discussion though, this “double layer” of tax argument could be looked at another way. Namely, to the extent that taxes on non-residents adds to the domestic cost of capital, other countries that apply such taxes will give a compensatory lift in returns to non-residents, including New Zealanders, that invest in their country to compensate them for their tax charge.

This is illustrated by expanding on the above example.

CASE 5

| Country A (20% tax) (33% NZ tax) |

Country B (zero tax) (33% NZ tax) |

New Zealand (33% NZ tax) |

|

| Returns after Tax | 7.4% | 6% | 6.7% |

Therefore, while New Zealanders investing offshore may legally pay taxes to two countries, they may only bear the economic incidence of the New Zealand tax. In economic terms, they only pay one layer of tax.

Second, if the pre-tax returns do not rise to offset the tax on non-resident investors, the foreign tax penalises New Zealand by reducing the overall returns to New Zealand from offshore investment. But there is nothing New Zealand can do to avoid that penalty. Lowering the tax rate applied to foreign-sourced income merely shifts the burden onto other New Zealanders.

2.8 The role of tax treaties and tax administration considerations

There are considerations arising for the tax administration and in the negotiation of double taxation agreements with other competent authorities that must be considered in any tax policy developments. We must consider how other jurisdictions will view our actions.

As explained earlier in this document, New Zealand taxes residents on their worldwide income, and, since the early 1960’s, has allowed a credit both unilaterally and in terms of tax treaties for foreign income tax paid on any foreign income derived by a resident. The tax credit is limited to the amount of the New Zealand tax that would otherwise be payable. The effect is the resident pays the higher of the two countries’ rates.

Under the twenty four tax treaties we have with foreign countries our residents receive certain benefits. The major benefit that they receive is certainty of tax treatment in the foreign country, i.e., the treatment guaranteed by treaties which follow international norms. More specifically, they commonly receive the following benefits:

- exemption of foreign tax on foreign profits not attributable to a branch in the foreign country.

- reduced or nil rates on investment income earned in the foreign country.

- a guarantee of tax credits in New Zealand for any foreign tax paid in accordance with the treaty.

- procedures for corresponding adjustments in one country when transfer pricing adjustments are made in the other In other words, if one country increases the returned profit of one affiliate, the other country may reduce the profits of the other affiliate).

- mutual agreement procedures between the tax authorities to deal with other cases of difficulties which might arise an render the taxpayer liable to double taxation. Examples are the clashing of residence rules and the clashing of source rules (For example, both countries may under their domestic tax laws treat a taxpayer as a resident and seek to tax that taxpayer on their worldwide income.).

- some protection against changes in legislation in the foreign country (where such legislation is contrary to the provisions of the treaty, the treaty normally prevails).

In contrast to residents, non-residents are taxed on New Zealand source income only. Full New Zealand tax rates are levied on net business income according to normal deductibility concepts. Lower rates are levied on investment income (dividends, interest and royalties) but the lower rates are applied to gross income with no deduction of expenses.

The underlying concept under our tax treaties is to reduce tax rates on non-residents on a reciprocal basis within the protection of a treaty and thus leave tax havens out in the cold.

From the point of view of the tax authorities the tax treaties have a number of benefits. The major one is the ability to obtain information from the other country. This is of crucial importance for our Inland Revenue Department in combating avoidance and evasion.

The overall policy direction for New Zealand over the last 20 years has been to follow the OECD recommendations to use such treaties to remove obstacles to the flow of capital and people, and to combat international evasion/avoidance through the exchange of information. In practical terms that means that we have reduced our tax rates on non-resident within the protection of a tax treaty while at the same time obtaining reciprocal benefits for New Zealand residents in relation to their tax exposure in those other countries. Benefits are granted to taxpayers on whom information and verification can be obtained in line with the exchange of information provisions of the treaty. By reducing domestic rates within the protection of treaties this has helped to combat international evasion and avoidance.

2.9 The relationship between domestic and international tax

The above discussion indicates that there is no one simple system for taxing cross border income flows that meets all objectives. Either system, that is, source or residence taxing, has advantages and disadvantages. The effect of not taxing residents on their worldwide income and the way taxes on non-residents can influence the relative rates of return between domestic and foreign-sourced income means that there is a connection between the two arms of international tax policy.

The aim of the Government must be to equalise as far as possible the rate of return on imported and exported capital by levying an appropriate net tax on income flowing from both sources.

The basic logic underlying this approach is as follows:

- New Zealand taxes should not affect residents’ decisions between investing locally or offshore, provided New Zealand applies the same tax treatment to both their domestic and offshore sources of income;

- when New Zealand taxes the foreign-sourced income of New Zealanders at lower rates than domestic-sourced income, New Zealanders receive an implicit increase in the after-tax return on their offshore investments.

- taxing non-residents can offset this implicit increase in the return, since it raises pre-tax rates of return in New Zealand relative to offshore and provides a further implicit incentive to invest onshore.

For the purposes of this discussion, we refer to this link between the taxes imposed on residents and non-residents as the “see-saw” relationship. In purely theoretical terms, the “see-saw” relationship would require the aggregate tax rate on cross-border income flows to sum to around the New Zealand corporate tax rate. Theoretically, under the “see-saw” the choice appears to be between explicitly double taxing residents on their foreign-sourced income or imposing a hidden additional cost through a higher domestic cost of capital. In practice the link is not so definite.

The “See-saw” Relationship

In its simplest form, the “see-saw” relationship arises because to the extent that taxes on non-residents are recovered by the non-resident from the New Zealand business, they in effect raise the rates of return in New Zealand relative to the world non-taxed rate of return.

Further, if New Zealanders are taxed more lightly on their offshore investments than on their domestic investments, then the tax system encourages them to invest offshore. Taxing non-residents can offset this bias by this increase in the rate of return, thereby making New Zealand a more relatively attractive location for residents to invest.

Implementing a pure application of the see-saw relationship would impose other costs on New Zealand if it raises the domestic cost of capital facing businesses already producing and investing in New Zealand. The choice of tax rate on non-residents involves therefore a complex trade-off that takes into account and balances all these factors.

If New Zealand applied the deduction approach while other countries applied the exemption and credit approaches, New Zealand resident international investors would be competitively disadvantaged vis-à-vis their foreign rivals. The situation would be akin to New Zealand exporters that have to compete against subsidised producers from other countries.

There is nothing New Zealand can do to remove either implied or direct subsidies given by other countries. Offering competing subsidies to New Zealand exporters and offshore investors only serves to make New Zealand worse-off by making it more attractive for New Zealanders to invest offshore. Applying the same tax treatment to foreign-sourced income as other countries maintains the competitiveness of New Zealand based international investors, but potentially at the expense of the competitiveness of the New Zealand economy.

In practical terms, the realistic option for the Government is to have some combination of taxes on both residents and non-residents.

2.10 Foreign tax credits received by non-residents

When non-resident investors receive full credits for taxes paid in New Zealand, each dollar of New Zealand tax is fully offset by a reduction in home country taxes. The non-resident’s tax bill remains constant. Taxing non-residents in these situations transfers revenue from the foreign country to New Zealand. Under these circumstances, New Zealand is able to raise tax revenue without deterring foreign investors and without increasing domestic interest rates or the domestic cost of capital.

If all non-residents are taxed currently by their home country and receive credits for New Zealand taxes, then the best policy for New Zealand would be to tax non-residents at least up to the level of those credits. If non-residents received tax credits in their own country of residence for foreign-sourced income they earn through their New Zealand operations, New Zealand should also tax those earnings. However, most countries do not currently tax income earned by a New Zealand subsidiary, so New Zealand does not get “free” revenue from applying the company tax, even though those earnings may be eventually taxed by the home country, with a credit for New Zealand taxes, when the income is distributed via dividends. The value of the deferred tax credit reduces the cost of the New Zealand tax, but does not offset it completely.

Most countries do not provide full credits for taxes paid overseas or restrict when their credits can be used. To the extent that these limitations cause a double tax effect to arise, the advantages gained from taxing non-residents can be reduced.

2.11 Other important considerations

2.11.1 Compliance and administrative costs

In the course of designing or evaluating an international tax regime, it is also important to incorporate the Government policy of minimising compliance costs, both the costs taxpayers incur when complying with their obligations under the regime and the costs that the Government incurs with the administration of the regime.

It is important to note, however, that there is a further trade-off in the compliance costs area. Simply put, the trade-off is between accuracy and simplicity. Improving the accuracy with which the income tax regime measures cross-border income flows or reduces the scope for tax planning opportunities tends to increase the compliance and administrative costs arising from the international tax regime. Balancing these trade-offs is not straightforward.

For instance, the company tax regime is of necessity more complex than the source deduction system on wages. For the first regime, full accrual accounting records with their supporting administration and analysis must be maintained. For the second regime, a more straightforward calculation to determine a specific deduction from a cash payment must be made. The additional work involved imposes higher compliance costs than the PAYE system, but the company regime is a key “backstop” to the effectiveness of the PAYE regime. Without the company regime, it would be very attractive for taxpayers to convert wage and salary income into company income and remain untaxed on that income until it is distributed to the ultimate shareholders. It would also be attractive for them to defer investment income taxation through the same mechanism.

Similarly, taxes on the foreign-sourced income of residents are a key “backstop” for the domestic income tax regime. They may be more costly to enforce and comply with than domestic taxes, but the regime plays an important role in protecting the integrity of the whole tax system as it applies to New Zealanders.

For the Government, considerable weight is given to compliance costs in the design of the policy and its day to day operation.

2.11.2 Minimising tax planning opportunities

Some taxpayers develop complex arrangements to reduce their tax liabilities in a jurisdiction by exploiting differences in tax treatments across countries and different forms of income, by recharacterising in legal terms the source of their income, its type, or their place of residence.

Such activities can impose additional “deadweight costs” on New Zealand as a whole by:

- encouraging taxpayers to use resources to design legal and financial structures to reduce New Zealand tax. Such expenditure is socially wasteful as it is directed at “gaining a larger share of the pie” rather than at “making the pie larger”;

- encouraging poor investment decisions by artificially altering the after-tax rates of return to alternative investments; and

- requiring the Government to impose costs on business by the complexity of the measures needed to address this activity and the higher rates of tax needed to raise the same amount of revenue (ie., to make up for the resultant erosion of the tax base).

Tax planning can best be countered by ensuring that, as far as practical, tax is levied on a broad income tax base at low rates. This broad base, low rate approach is reflected in the Government’s international and domestic tax reform programme.

New Zealand can tax non-residents only on income sourced in this country. The non-resident base is best protected by, as far as practical:

- applying uniform rates of tax on different forms of New Zealand income; and

- having clear and robust rules determining when income is sourced in New Zealand.

The measures canvassed in this document relating to foreign direct investment, transfer pricing and thin capitalisation aim to meet these objectives.

2.11.3 Multinationals and international tax

As discussed above, applying the residence principle (that is levying equal tax on both the domestic and offshore income of New Zealand residents) reduces any tax incentives to invest offshore and protects the tax base. Strictly, this principle applies to New Zealand resident companies only to the extent they have New Zealand resident shareholders. Application of this principle to a New Zealand resident company owned fully or partially by non-residents would mean those non-residents are subject to New Zealand tax on their foreign income. This can make New Zealand an unattractive base for offshore investment by multinationals. Consideration needs to be given to whether this problem can be ameliorated without reintroducing artificial incentives for New Zealand shareholders to invest offshore and without exposing the tax base to avoidance problems.

2.11.4 Policy sustainability

Investments are, by their nature, a “forward-looking” activity and once initiated they are often costly to reverse. Investment thrives in a world where the rules are understood and permanent. Tax changes that can be reversed at a later stage after investments have been made would be unwelcome. These concerns tend to be of greater importance to foreign investors who often feel more exposed to changes in policy.

To avoid deterring investment, it is important to have broad community support for major tax rules so that they are seen as sustainable in the future. To engender this support, the Government intends to consult widely before deciding on the direction and nature of policy initiatives.

In addition, adopting reforms based on a consistent framework will build credibility over time.

It is therefore very important that individual reforms to the international regime are consistent with an overall economic and policy framework for international tax policy and that the long-term direction of policy be signalled clearly and adhered to over time.

2.12 Conclusion

In the course of gathering revenue, the income tax regime has a number of effects on economic behaviour.

Of particular concern is the ability of a poorly designed income tax system to:

- deter foreign investment and the associated benefits of new capital, skills and technology it embodies;

- increase the domestic cost of capital for New Zealand firms, thereby reducing their international competitiveness;

- encourage patterns of foreign and domestic investment that do not make the most efficient use of New Zealand’s resources; and

- make New Zealand an unattractive base for foreign multinationals to invest offshore.

In principle, the international tax regime should be designed in such a manner as to reduce these “deadweight costs”. However, the process of designing a practical international tax regime that meets the Government’s economic policy objectives and international obligations is a complex process involving numerous trade-offs between various objectives.

Theoretically, the broad features that the international tax regime should possess to be consistent with the Government’s economic policy objectives are in particular:

- the effective tax rates applying to the New Zealand-sourced income of non-residents should be as uniform as possible across alternative investments; and

- the effective rates of tax applying to the foreign-sourced income of residents should be as uniform as possible across investments.

In both cases, this requires accurate measurement of income and uniform statutory tax rates on each type of income.

The rates of New Zealand taxes imposed on inward and outward investment need to reflect the desirability of minimising the cost of capital to New Zealand and encouraging investment into New Zealand. So far as possible the rate structure should not provide an incentive for New Zealanders to invest offshore rather than here. The “see-saw” relationship is a theoretical framework for considering this issue. However, tax rules on investment flows also need to be practical and fair.

Consideration also needs to be given to:

- minimising opportunities for tax planning;

- the compliance and administrative costs of the regime. Reducing such costs inevitably involves some sort of trade-off between the accuracy of income measurement and the simplicity of the regime;

- ensuring the regime is sustainable in the longer term and sends clear signals to potential foreign investors about New Zealand tax structures;

noting that a well designed regime will leave business investment decisions the same as they would be in the absence of New Zealand taxes.