28 January 2021

Coversheet

Advising agencies: The Treasury, Inland Revenue

Decision sought: Note the analysis in this report.

Proposing Ministers: Minister of Finance, Minister of Revenue

SUMMARY: PROBLEM AND PROPOSED APPROACH

Problem Definition

What problem or opportunity does this proposal seek to address? Why is Government intervention required?

Summarise in one or two sentences

COVID-19 related public health restrictions at Alert Level 2 or above can create short and severe economic shocks. Cumulatively, they stress firm balance sheets and risk delivering unequitable outcomes. The effects of these shocks on firm revenue, coupled with uncertainty of the nature of Government support in the event of a virus resurgence, risks higher unemployment and firm failure as firms are disincentivised from or unable to employ people or invest.

Summary of Preferred Option or Conclusion (if no preferred option)

How will the agency’s preferred approach work to bring about the desired change? Why is this the preferred option? Why is it feasible? Is the preferred approach likely to be reflected in the Cabinet paper?

Summarise in one or two sentences

The recommended approach was to introduce and pre-announce a new one-off Resurgence Support Payment (RSP) available to all firms in the event of an increase from Alert Level 1 to Alert Level 2, 3, or 4. The recommended sub-options were:

- To make the RSP available to all firms that experience a drop in revenue of 30% or more over a 14-day period as a result of higher Alert Level restrictions; and

- To pay the lesser of:

- $1500 plus $400 per full-time employee (FTE) (up to a cap of 50); or,

- Two times the experienced drop in revenue over the 14-day period.

These options were preferred because they:

- allow businesses to better plan ahead;

- meant the RSP would be readily deployable by Inland Revenue in the event it is needed (following the passing of legislation and building the system);

- are fiscally sustainable;

- cushion the economic blow of higher Alert Levels to firms, limiting scarring effects;

- support the transition up Alert Levels, boosting social licence for public health regulations;

- encourage the shift to a more COVID-19 resilient economy;

- ensure that some low revenue firms do not gain disproportionately from the RSP, in excess of their needs to meet fixed costs and transition costs; and

- target vulnerable but viable firms.

SECTION B: SUMMARY IMPACTS: BENEFITS AND COSTS

Who are the main expected beneficiaries and what is the nature of the expected benefit?

Monetised and non-monetised benefits

The RSP will support the national effort to eliminate COVID-19, for the benefit of all New Zealanders.

The RSP provides additional financial support to firms to allow them to continue to meet fixed costs and cover costs associated with an escalation of Alert Levels, and quickly continue operations as soon as Alert Level restrictions allow. In turn, this benefits individuals employed by those firms.

Whilst the Payment is available to all businesses, SMEs are the main financial beneficiaries. This recognises that the vast majority of businesses in New Zealand employ fewer than 50 people, and that smaller firms are less resilient to economic shocks than larger businesses.

However, it is important to recognise that while larger firms are more resilient on average, larger firms can need support too. Not allowing large firms to access this form of support would disadvantage firms just on the cut-off, such as firms with 51 employees. This could make it harder for these firms to survive and may incentivise them to get rid of staff in order to become eligible, which we do not want to encourage. For this reason, the RSP will be available to firms of all sizes.

Where do the costs fall?

Monetised and non-monetised costs; for example to local government or regulated parties

The fiscal costs fall to the Crown, however Treasury analysis suggests the long-term fiscal, economic and social impacts of no action would likely be greater.

What are the likely risks and unintended impacts? How significant are they and how will they be minimised or mitigated?

Compressed timelines create policy development, delivery, and communications risks, which could lead to:

- payments being more widely available than is efficient, or being paid to unviable firms, at unnecessary fiscal cost;

- damaging the social capital that is critical for the success of the COVID-19 public health strategy; and

- business confusion around the access to the scheme, meaning firms may lose out on support they are entitled to.

The main mitigations we have undertaken include:

- to agree, via Joint Ministers and Cabinet, detailed design rules in order to enable Inland Revenue to build the scheme at pace with as much certainty as possible;

- a series of measures to boost the integrity of the scheme and minimise gaming risks;

- taking a co-ordinated cross-Government approach to communications;

- engaging with external business stakeholders to inform the design of the scheme and promote its availability, ensuring the widest audiences are reached.

SECTION C: EVIDENCE CERTAINTY AND QUALITY ASSURANCE

Agency rating of evidence certainty?

How confident are you of the evidence base?

Evidence drawn on to inform the design of the RSP include:

Regular, detailed qualitative engagement with the business community and monitoring of the effectiveness of existing supports

Evidence was consistent from a diverse range of groups that:

- greater certainty about the nature of government support in the event of a resurgence was critical, which led the decision to announce the support would be available in advance of any escalation of Alert Levels;

- firm balance sheets in the most affected sectors were increasingly stressed; and

- additional debt products were less appropriate.

Evaluation of the uptake of the Small Business Cashflow Scheme (SBCS) also evidenced the waning appetite for debt. The Payment was therefore designed as a grant.

Real-time transaction data, which showed the impacts of Alert Level on revenue

- Xero data on revenue drops experienced by firms month-to-month throughout 2020 informed our understanding of Alert Level impacts.[1]

- This, alongside information on uptake of the various wage subsidies, allowed us to estimate the number of firms facing significant revenue drops at different Alert Levels and led to the 30% revenue drop test.

Survey data on firms’ cost structures and cash reserves

- The Annual Enterprise Survey (AES)[2] provided insight into the fixed, variable, and wage costs usually faced by firms of varying size, allowing us to understand the scale of need when normal revenue streams are disrupted.

- This gave quantitative support to insights gathered through stakeholder engagement about the difficulty in meeting fixed costs under higher Alert Level restrictions.

- Better 4 Business (B4B)[3] research into firms’ cash reserves also echoed messages from stakeholders concerning balance sheet stress and eroded financial resilience.

This evidence supported the case for grant-based support.

Modelling and analysis of the macro and microeconomic impacts of Alert Levels on the economy.

- The Treasury prepared estimates of economic activity under different Alert Levels for each industry at regular intervals during 2020, updating the analysis as new data became available.

- These estimates were initially assumption-driven, based on macroeconomic data, and were updated as new data (including high frequency indicators and information on the uptake of the Government’s financial support) enabled re-examination of previous assumptions.

- The Treasury also commissioned modelling of the impacts of border closure and Alert Level settings on sectors and regions of the economy, which was conclusive in demonstrating impacts across all sectors and particularly acute effects on tourism and hospitality firms. This analysis is not yet published.

To be completed by quality assurers:

Quality Assurance Reviewing Agency:

A joint Regulatory Impact Analysis quality assurance panel with representatives from the Treasury and Inland Revenue has reviewed the Supplementary Analysis Report for the above legislative/regulatory proposal in accordance with the quality assurance criteria set out in the CabGuide.

Quality Assurance Assessment:

A joint Regulatory Impact Analysis quality assurance panel with representatives from the Treasury and Inland Revenue has reviewed the Supplementary Analysis Report “Resurgence Support Payment Supplementary Analysis Report” produced by the Treasury and Inland Revenue, dated 28 January 2021. The panel considers that it meets the Cabinet requirements to support its decision.

Reviewer Comments and Recommendations:

No further comments.

Supplementary analysis

SECTION 1: GENERAL INFORMATION

1.1 Purpose

The Treasury and Inland Revenue are solely responsible for the analysis and advice set out in this Regulatory Impact Statement, except as otherwise explicitly indicated. This analysis and advice has been produced for the purpose of informing:

- stakeholders to be consulted on a government exposure draft of planned legislation (amendments to the Tax Administration Act 1994)

- final decisions to proceed with a policy change to be taken by or on behalf of Cabinet

1.2 Key Limitations or Constraints on Analysis

- What issues are in or out of scope? e.g., Ministers may already have ruled out certain issues.

- What are the limitations on the range of options considered and the criteria used to assess options?

The RSP was recommended following direction from the Minister of Finance to deploy a new economic response initiative that was limited in scope to support the transition of viable firms to new economic settings; be flexible to support firms in higher Alert Level settings, be fiscally sustainable; and readily deployable. This limited the options to forms of support that could reach affected businesses quickly, and therefore risk issuing payments to firms who may not always need it. However, the criteria used to assess options indicated that in order to mitigate potential economic scarring effects, and with tight application criteria built in, this was a worthwhile trade-off.

- What limitations exist in relation to the evidence of the problem?

- What is the quality of data used for impact analysis?

- What limitations may there have been on consultation and testing?

The Treasury engaged with a diverse range of business groups throughout 2020, including on the specific design parameters of a new Payment in the run up to preparing the Cabinet Paper.

Those consulted on the RSP design included Business New Zealand, the Council of Trade Unions, the Auckland Chamber of Commerce, the Corporate Taxpayers Group, the Chartered Accountants Australia and New Zealand, and Māori and Pacific business leaders.

In addition to the pace with which consultation was undertaken, a limitation of this evidence continues to be the significant uncertainty around global events and changing, potentially unpredictable domestic conditions.

Notwithstanding this uncertainty (which is detailed in the Treasury’s Pre-election Economic and Fiscal Update and Half-Year Economic Update publications), the Treasury’s assessment of the impacts of Alert Level restrictions on economic activity and the related risks to aggregate firm solvency over potential series of virus outbreaks led to the conclusion that there was a gap in the support available.

This assessment was informed by data from sources including the aforementioned AES, B2B surveys, Xero, and other modelling. The Treasury judges the quality of this data to be both high and comprehensive.

- What are the limitations on the assumptions underpinning the impact analysis?

We assume that patterns of revenue impact experienced by firms are broadly consistent with those seen in periods of elevated Alert Levels throughout 2020. As such, we assume that the take up of the Payment would be broadly in line with that of other forms of COVID-19 financial support tools to date, including the Wage Subsidy (WSS) and SBCS. Whilst the design of the Payment reflects the greater information available than when the pandemic first began, the uncertainty related to the nature of any future COVID-19 outbreak means the impacts may be different each time.

1.3 Responsible Manager (signature and date):

[Withheld under section s 9(2)(a) of the Official Information Act 1982]

Jean Le Roux

Transitions, Regions and Economic Development Growth, Productivity and Services Directorate

The Treasury

28 January 2021

SECTION 2: PROBLEM DEFINITION AND OBJECTIVES

2.1 What is the current state within which action is proposed?

Set out the current state, e.g.,

Nature of the market; Industry structure; Social context; Environmental state.

The Treasury’s Pre-election Economic and Fiscal Update provided the context in which the advice on the RSP was developed. The subsequent Half-Year Economic Update was published on 17 December 2020.

Both documents underline that the COVID-19 pandemic continues to cause widespread economic and social disruption around the world, and the effectiveness and timing of the distribution of vaccines were still unclear at the time of writing.

Both reports present a central scenario wherein New Zealand’s border restrictions ease from 1 July 2021 and will lift from 1 January 2022, alongside alternative scenarios attempting to benchmark possible downside scenarios. In the meantime, New Zealanders should be prepared for the potential that whilst most of the economy will operate normally the majority of the time, Alert Levels may temporarily escalate.

2.2 What regulatory system(s) are already in place?

- What are the key features of the regulatory system(s), including any existing regulation or government interventions/programmes? What are its objectives?

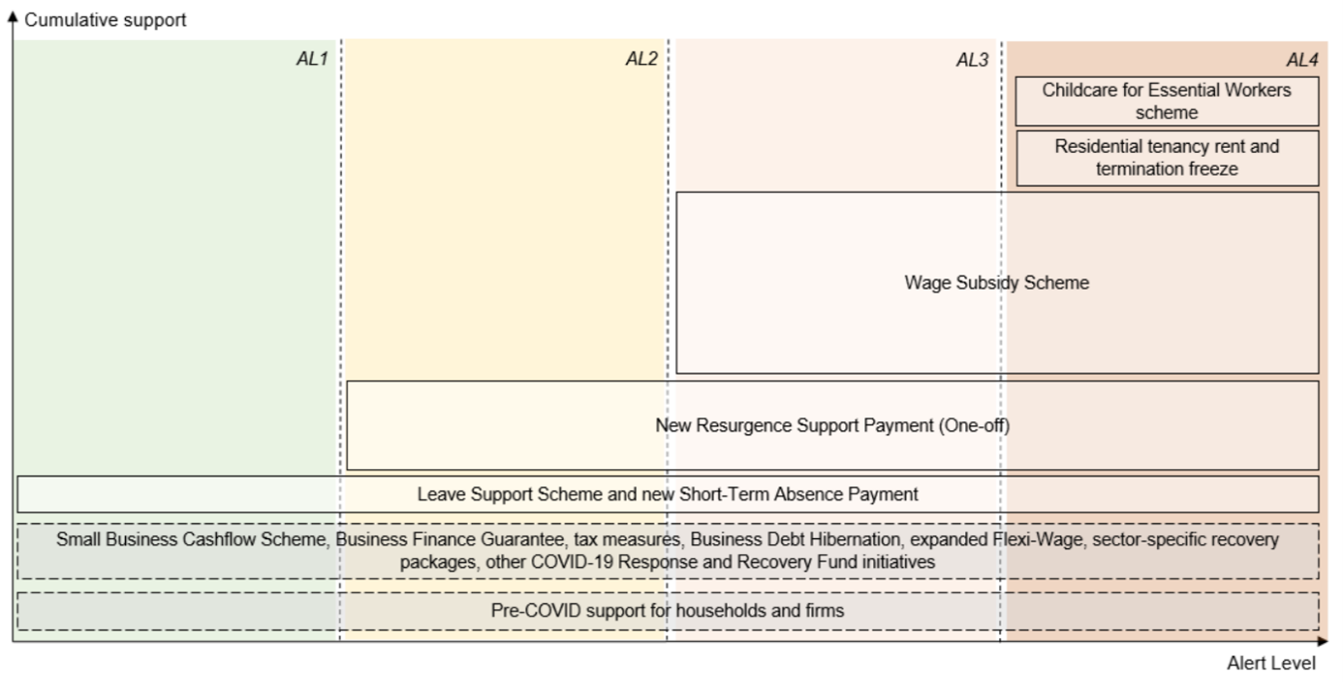

The below diagram summarises the economic support landscape as of January 2021, including with the addition of the RSP, at different Alert Levels. The suite of interventions support the Government’s first overarching objective to keep New Zealanders safe from COVID-19, including by protecting jobs and livelihoods, and strengthening the economy. It does so by ensuring a package of financial support is in place for businesses and individuals in the event of Alert Level escalations following future resurgences of COVID-19 in the community, with the aim of limiting the economic and social impacts if outbreaks occur. It also seeks to reduce the risk of resurgences by supporting workers to stay home when sick. These goals are complementary, as protecting New Zealanders from the virus will also support economic activity resuming quickly after any outbreaks.

- Why is Government regulation preferable to private arrangements in this area?

Public health restrictions attempt to provide protection from COVD-19; firmly an intervention that should and could only be undertaken by government. However, the economic costs of the public health restrictions (such as Alert Level changes), land upon individuals and businesses. It is appropriate for government to share some of these costs, consistent with the provision of public goods.

The Treasury’s latest estimates that the negative impacts to GDP from Alert Level restrictions (relative to pre-pandemic levels) are:

- -25% to -30% at Alert Level 4

- -15% to -20% at Alert Level 3

- -6% to -10% at Alert Level 2

- -3% to -5% at Alert Level 1.

These are significant impacts with distributional consequences and scarring effects that require interventions at a scale only the Government can provide via broad-based support.

- Has the overall fitness-for-purpose of the system as a whole been assessed? When and with what result? What interdependencies or connections are there to other existing issues or on-going work?

Part of the rationale for the introduction of a new RSP at Alert Level 2 was to fill a gap in the support available to businesses as the cumulative impacts of higher public health restrictions added additional stress to balance sheets.

In designing the intervention, officials attempted to achieve consistency between the RSP, WSS and the SBCS, where sensible, so as to reduce business confusion.

This is reflected in a number of the settings proposed above for the RSP, including many of the settings relating to business declarations and business eligibility.

There are other settings that are not in alignment. Some are based on policy grounds, such as the differing revenue drop thresholds under the RSP and WSS reflecting the schemes’ different purposes at different Alert Levels. Others are based on the fact that there will be different agencies implementing the schemes, with different system capabilities and different approaches to achieving necessary scheme integrity.

2.3 What is the policy problem or opportunity?

- How is the situation expected to develop if no further action is taken, and why is this a problem? (This is the basis for comparing options against each other).

- What is the nature, scope and scale of the loss or harm being experienced, or the opportunity for improvement? How important is this to the achievement (or not) of the overall system objectives?

- What is the underlying cause of the problem? Why cannot individuals or firms be expected to sort it out themselves under existing arrangements?

- How robust is the evidence supporting this assessment?

The estimated negative impacts from Alert Level restrictions (relative to pre-pandemic levels) described in box 2.2 are significant, with distributional consequences and scarring effects that require interventions at a scale only the Government can provide through broad-based support.

We know that Alert Level restrictions have an uneven impact across industries. Industries that find it costly to adapt operations for delivery under Alert Level settings, given the general necessity of in-person, on-site service provision, are under significant pressure. “Essential Services” definitions were used to form a view of which firms were able to operate at the higher Alert Levels. This assessment leveraged off work that was being undertaken by MBIE during the early stages of the COVID response to assess demand for Personal Protection Equipment (PPE) across essential industries, as well as work that was done between Treasury and MBIE on assessing uptake of the WSS.

On top of this, firms suffer from the wider demand-side shocks due to reduced tourism activity, the decline in people movement, and economic conditions. Aggregate demand impacts from border closure particularly reduce demand for tourism-related industries such as accommodation, recreational activities etc. Statistics NZ Tourism Satellite Account information was used to inform a view on which industries were most impacted and the relative importance of international vs domestic tourism.

The Treasury also commissioned modelling of the impacts of border closure and Alert Level settings on sectors and regions of the economy, which was conclusive in demonstrating impacts across all sectors and particularly acute effects on tourism and hospitality firms.

2.4 What do stakeholders think about the problem?

- Who are the stakeholders? What is the nature of their interest?

- Which stakeholders share the Agency’s view of the problem and its causes?

- Which stakeholders do not share the Agency’s view in this regard and why?

The Treasury engaged with Business New Zealand, the Council of Trade Unions, the Auckland Chamber of Commerce, and Pacific, Māori and Iwi business leaders in developing the RSP. Inland Revenue also engaged with the Corporate Taxpayers Group and the Chartered Accountants Australia and New Zealand. Their interest in the Payment was on behalf of business owners and employees throughout New Zealand.

The engagement followed several months of conversations between the Treasury and business stakeholders on the impacts of higher Alert Levels and border settings on different sectors. There was extremely strong consensus from across the spectrum that providing greater certainty on the nature of Government support in the event higher Alert Levels were in place would be critical for businesses to plan and right-size smoothly. The RSP responded to this consistent message.

Stakeholders were broadly supportive of the approach to create greater certainty on the landscape of government support, and particularly welcoming of measures that would address non-wage costs in addition to the costs covered by the WSS.

There was strong feedback that the integrity of the schemes will be critical, with both Māori and Pacific business leaders raising concerns about possible gaming of support available. It was suggested that the communications approach to the package should be accompanied with clear guidance to maximise accessibility of the schemes, and partnerships with trusted community channels would aid access to the schemes and be critical in helping SMEs – which would likely be most vulnerable – prepare now for future outbreaks. Officials are using this feedback to inform the communications strategy.

2.5 What are the objectives sought in relation to the identified problem?

- Objectives must be clear and not pre-justify a particular solution. They should be specified broadly enough to allow consideration of all relevant alternative solutions.

- Where there are multiple policy objectives it should be clear how trade-offs between competing objectives are going to be made and the weightings given to objectives – not just those in direct conflict.

- For further guidance, see 2.3 of the Guidance Note on Best Practice Analysis https://treasury.govt.nz/sites/default/files/2018-03/ia-bestprac-guidance-note.pdf

The purpose of the RSP is to provide support for businesses’ to meet fixed costs and costs when transitioning from Alert Level 1 to Alert Level 2 or above, in a fiscally sustainable way. The objectives, which formed the criteria against which different options were assessed, are as follows:

- Support firms to maintain viability and employment levels across escalations in public health restrictions;

- Support firms to pay fixed costs (such as rent) if they are struggling to do so as a result of escalated Alert Levels;

- Share the cost associated with escalated Alert Levels between Government, firms and across economic sectors; and

- Encourage the shift to a COVID-19 resilient economy.

This required the following scheme attributes, which informed the selection of options (see section 3):

- Resilience to different public health scenarios

- Providing business certainty, so firms can better plan ahead

- Complementarity with existing schemes; and

- Fiscal sustainability.

Trade-offs

In order to support firms to maintain viability and employment levels (objective (a)), there will necessarily be payments made to some firms who would survive anyway, and others that may not have been viable in the medium term (see objective (d)). However, from a fairness perspective, there is a case to equally share the cost of the exogenous shock provided by the pandemic (c). The critical weighting here is in favour of mitigating scarring economic effects for the long-term benefit of all New Zealanders, and designing a scheme that is resilient / can pay out quickly (see box 3.1). The Payment was therefore designed to be available to all firms but with design features built in to target the most affected and those with the fewest resources to respond to the restricted market settings created by higher Alert Levels.

SECTION 3: OPTION IDENTIFICATION

3.1 What options are available to address the problem?

- List and describe the key features of the options. Set out how each would address the problem or opportunity, and deliver the objectives identified.

- How has consultation affected these options?

- Are the options mutually exclusive, or do they or some of them work in combination?

- Have non-regulatory options been considered? If not, why not?

- What relevant experience from other countries has been considered?

The first-order options were as follows:

A. Front-loaded WSS-based scheme

Lump sum worth 2 weeks of the wage subsidy paid for every change in AL to firms meeting a 40% revenue drop test, with a labour market attachment requirement:

Assessment: maintains employment but does not address other costs associated with Alert Level escalation; 40% threshold aligned with WSS but likely too high at Alert Level 2; fiscally expensive.

B. Amended WSS-based scheme

As above, but restricting payments to escalations in ALs only, and allowing only one payment every four weeks.

Assessment: potentially less frequent payments may do more to encourage transition, but challenges of option A remain.

C. Lump-sum AL2+ grant [this was the recommended and agreed approach]

Adapted form of options A&B that is:

- Less generous per FTE, with a per-firm and per-FTE component to reflect fixed costs;

- Subject to a less onerous revenue drop test, to reflect impact of AL2 on businesses;

- Paid every time there is an escalation from AL1 to AL2 or above; and

- Without a labour market attachment condition, but firms would declare they are viable.

Assessment: responds to business feedback that more support was needed for fixed costs (e.g. rent); less generous, thereby better facilitating transition and potentially more equitably sharing the cost between Government and the private sector.

D. Ongoing AL2+ grant

As (C), but paid on an ongoing basis for every week a region or nation is at AL2 or above

Assessment: benefits of Option C but less likely to facilitate transition, fiscally expensive.

E. Time-limited AL2+ grant

As (D), but with a fixed number of weeks that a firm can claim for over the life of the scheme.

Assessment similar to (D); greater cushioning provided for firms than (C) but more expensive.

The Treasury also considered grants directly aimed at hospitality firms and others directly identified in public health regulations as needing to make adaptations in order to meet social distancing and hygiene requirements. This was ruled out due to the considerable boundary issues involved in categorising businesses by strict sectors.

Option C was recommended in light of its strengths in delivering the overall objectives described in box 2.5 above.

The sub-options that were consequently considered, which are largely mutually exclusive, are as follows:

The public health settings that would trigger the scheme’s activation

Based on the above objectives, we recommended that any new grant scheme should be available to businesses based on an escalation to AL2 or higher. This ties the duration of any payments to the time at which many businesses will continue to face substantial cost from public health restrictions.

In the event that such an escalation is in one region, the case for only starting the scheme in that region was considered.

Regional targeting would pose operational challenges – for example, firms that are registered in a different place to their economic activity, or subject to spillovers from restrictions in a neighbouring region. Those challenges mean that regional targeting will come with hard boundary cases, and would create operational difficulties for IR, though it is technically feasible.

As an alternative, there was an option for Ministers to choose to turn the scheme on nationally or by region in the given circumstance. Given that this could undermine business certainty on the support received, which was a significant part of the policy aim informed by consultation, it was concluded that a commitment to provide the RSP when a region or the country was at AL2 or above would be subject to final Cabinet approval at the time of an escalation event.

Whether to make the support time-limited, or an ongoing grant at certain Alert Levels

The key strategic choice was between supporting firms to adapt to the new restrictions through a one-off or time limited payment, or maintaining as many existing firms or jobs as possible by providing ongoing, certain, support for the remainder of the pandemic. The former approach was judged to best support the objectives, in light of the greater fiscal sustainability associated with one-off payments; likelihood of supporting fewer non-viable firms; and potential to incentivise a transition to new market conditions.

The conditions under which firms would be eligible

Whilst all means of delivering targeted sector or viable firm support are imperfect, on balance, we recommended taking a similar approach to the Wage Subsidy Scheme and relied on a revenue-drop test. This is because:

- It identifies those firms and sectors most affected by AL2 restrictions, whether that is due to the direct impact of public health restrictions or supply chain spill-overs; and

- It is well understood by businesses as a common means of determining eligibility for COVID-19 support measures.

The alternative identified was to specifically target firms that are subject to specific public health requirements by virtue of providing food and drink for on-premises consumption (hospitality). Treasury’s judgement, having consulted with delivery partners, is that doing so would be exceptionally challenging to define, audit, or operationalise; would create very difficult boundary issues for businesses to navigate and understand; and would create very high levels of customer contact and confusion.

The means of calculating the grant value

A grant to firms should be fiscally sustainable and ideally account for the fixed costs that firms face which scale relatively slowly with firm size and are hard to adjust quickly (such as rent and utilities), and variable costs that can adjust more quickly (such as wages and the transition costs associated with Alert Level changes).

In order to achieve this, we recommended that a grant value has a fixed and variable component using FTE[4] employees as a measure of firm size and variable costs.

Grant = base value per firm + ( FTE payment * FTE)

To ensure that some low revenue firms do not gain disproportionately from the RSP, we also recommended a design mechanism whereby the amount of payment is capped at two times the fortnightly drop in revenue that the applicant has signalled in its application.

This approach means the amount a firm receives will be the lower of the formula amount ($1,500 plus $400 per FTE) or two times the fortnightly drop in revenue. The Treasury estimated this would save a total of $30-50m in fiscal costs.

We also explored alternative ways of setting a grant relative to a firm’s size (for example, on the basis of a firm’s revenue or balance sheet), but doing so poses substantial operational challenges and would be more complex for businesses.

Whether to restrict the grant to SMEs.

Larger firms have stronger balance sheets and access to credit and cash buffers, and the value of the payment will be much less material to their business decisions. However, the fiscal impact of providing the RSP to all firms without a cap on FTE was estimated to be relatively low (given that the base value was a substantial proportion of the cost, and there are very few large firms in New Zealand). On balance, it was preferred to cap the amount of the RSP to firms at the equivalent of a payment to firms with 50 FTE, similar to the original design of the Wage Subsidy, which has the benefits of equal treatment in approach to supporting all businesses.

This was also supported by feedback gathered in consultation with stakeholders across the business community, who provided advice that the support would have strongest effect for SMEs.

Have non-regulatory options been considered? If not, why not? What relevant experience from other countries has been considered?

The Treasury explored whether demand-led schemes could be viable to support objectives including (a) and (d) above. It examined the UK’s ‘Eat Out to Help Out’ scheme, which subsidised meals out. It was concluded that the scheme would run counter to the public health goals at higher Alert Levels to subsidise and therefore incentivise eating out.

The IMF’s Policies for the Recovery published in October 2020 was also considered. The publication recommended fiscal strategies including “cash or in-kind transfers to support transition and target those in need, in the event of partial opening”, which supported the case for the approach taken to designing the RSP.

In addition, the Treasury engaged with officials in Australia to share ideas on building support schemes which targeted vulnerable but viable firms.

3.2 What criteria, in addition to monetary costs and benefits have been used to assess the likely impacts of the options under consideration?

3.3 What other options have been ruled out of scope, or not considered, and why?

- Comment on relationships between the criteria, for example where meeting one criterion can only be achieved at the expense of another (trade-offs)

Note: sections 3.2 and 3.3 from the original template are combined as the answers are strongly related.

The desired impacts are directly related to the objectives of the RSP:

- Support firms to maintain viability and employment levels across escalations in public health restrictions;

- Support firms to pay fixed costs if they are struggling to do so as a result of escalated Alert Levels;

- Share the cost associated with escalated Alert Levels between Government, firms and across economic sectors; and

- Encourage the shift to a COVID-19 resilient economy.

It was considered that grant-based support was more likely to support businesses to maintain viability and employment levels than debt-based alternatives, whilst being fiscally sustainable (given the quantum of funding set aside to respond to resurgence events if needed).

Whilst debt based support may help firms manage immediate cash flow issues, it can become restrictive and delay investment in transition as they divert cash from growth activities to financing costs.

Furthermore, firms are likely to be more risk averse than the Crown, which pools risk and has a large balance sheet, a long time horizon, and a public interest perspective.

An additional part of the rationale for the RSP in delivering the above objectives relates to the impacts on social license for the public health response.

Whilst the available evidence demonstrated a broadly high level of compliance with the public health restrictions during the outbreaks in 2020 (for example, traffic flows were much lower as a result of AL3 in Auckland), there was some evidence that the high degree of social capital that supported compliance with the longer national lockdown waned. In addition, at the time of designing the Payment, there was emerging evidence that compliance with restrictions overseas was waning, especially in cases where the economic support was judged to be insufficiently generous to incentivise people to self-isolate rather than work.

It was concluded that economic response measures can play a key role in maintaining ongoing social license for public health restrictions, both in compensating individuals for their compliance with restrictions, minimising the impact on jobs and economic wellbeing, and reinforcing social solidarity. Whilst this is a difficult impact to measure and accurately attribute to economic support, the counterfactual would be a significant risk to the health and wellbeing of all New Zealanders.

SECTION 4: IMPACT ANALYSIS

Marginal impact: How does each of the options identified in section 3.1 compare with taking no action under each of the criteria set out in section 3.2? Add or subtract columns and rows as necessary.

| Second-order design choice (see also box 3.1) | Association with AL settings | Payment format | Eligibility | Firm size | |||||

| No action | Pay on escalation to AL2 or higher | Pay businesses in an affected region or sector only | Ongoing throughout duration of AL | One-off, scaled to normal revenue levels | Revenue drop test | Firms subject to specific public health requirements | All firms but cap support at 50 FTE | No cap on FTE | |

| Maintain viability and employment levels when ALs increase | 0 | ++ Scale of firms supported limits scarring effects | + Targeting intention likely to encounter significant boundary issues (e.g. ignores supply chain interdependencies) | ++ Greater fiscal generosity likely to assist labour attachment and maintain firm viability. | + May not be enough in light of prolonged impacts of higher ALs | ++ All affected firms benefit; boundary cases diminished | + Targeted approach supports most affected by public health Orders, but with boundary and administrative issues | ++ Firms with <50 FTEs make up vast majority of NZ businesses. | + Marginal impact diminishes with marginal increase in FTE as larger firms likely to have stronger balance sheets and access to credit/cash buffers. |

| Support firms to pay fixed costs if they are struggling to do so as a result of escalated Alert Levels | 0 | ++ Reflects the evidence that higher ALs have significant impacts on most firms’ revenue. | |||||||

| Share the cost associated with escalated Alert Levels between Government, firms and across economic sectors; | 0 | + Risks delaying firms’ transition to new market conditions if Government pays indefinitely. | ++ Limiting support encourages firms to plan ahead and right-size to reflect new market conditions. The suggested formula approach is fiscally sustainable and scaled according to need. | ++ Reflects that smaller businesses have fewer resources to address the costs | ++ Reflects that smaller businesses have fewer resources to address the costs | ||||

| Encourage the shift to a COVID-19 resilient economy | 0 | ++ Smooths the path to new market conditions whilst mitigating scarring effects. | + Boundary issues mean some firms may benefit from a smoother transition than others, which raises questions of fairness. | ++ Smooths the path to new market conditions whilst mitigating scarring effects. | +/- Boundary issues mean some firms may benefit from a smoother transition than others, which raises questions of fairness. | ++ Reflects that smaller businesses have fewer resources to shift to new market conditions without significantly reducing employment | |||

| Overall assessment | ++ | + | + | ++ | ++ | +/- | ++ | + | |

Key:

++ much better than doing nothing/the status quo

+ better than doing nothing/the status quo

0 about the same as doing nothing/the status quo

- worse than doing nothing/the status quo

- - much worse than doing nothing/the status quo

SECTION 5: CONCLUSIONS

5.1 What option, or combination of options is likely to best address the problem, meet the policy objectives and deliver the highest net benefits?

The recommended approach was to introduce and pre-announce a new one-off Resurgence Support Payment available to all firms in the event of an increase from Alert Level 1 to Alert Level 2, 3, or 4. The recommended sub-options were:

- To make the Payment available to all firms that experience a drop in revenue of 30% or more over a 14-day period as a result of higher Alert Level restrictions; and

- To pay the lesser of:

- $1500 plus $400 per full-time employee (FTE) (up to a cap of 50), or,

- Two times the experienced drop in revenue.

These options were preferred because they:

- allow businesses to better plan ahead;

- meant the RSP would be readily deployable by Inland Revenue in the event it is needed (following the passing of legislation and building the system);

- are fiscally sustainable;

- cushion the economic blow of higher Alert Levels to firms, limiting scarring effects;

- support the transition up Alert Levels, boosting social licence for public health regulations;

- encourage the shift to a more COVID-19 resilient economy;

- ensure that some low revenue firms do not gain disproportionately from the RSP, in excess of their needs to meet fixed costs and transition costs; and

- target vulnerable but viable firms.

This approach was informed through consultation with Business New Zealand, the Council of Trade Unions, the Auckland Chamber of Commerce, and Pacific, Māori and Iwi business leaders in developing the RSP. Inland Revenue also engaged with the Corporate Taxpayers Group and the Chartered Accountants Australia and New Zealand.

The engagement on the specific design aspects of the RSP followed several months’ of conversations between the Treasury and these stakeholders on the impacts of higher Alert Levels and border settings on different sectors. There was extremely strong consensus from across the spectrum that providing greater certainty on the nature of Government support in the event higher Alert Levels were in place would be critical for businesses to plan and right-size smoothly. The RSP responded to this consistent message.

Stakeholders were broadly supportive of the approach to create greater certainty on the landscape of government support, and particularly welcoming of measures that would address non-wage costs in addition to the costs covered by the Wage Subsidy Scheme. There was strong feedback that the integrity of the schemes will be critical, with both Māori and Pacific business leaders raising concerns about possible gaming of support available. It was suggested that the communications approach to the package should be accompanied with clear guidance to maximise accessibility of the schemes, and partnerships with trusted community channels would aid access to the schemes and be critical in helping SMEs – which would likely be most vulnerable – prepare now for future outbreaks. This feedback has fed into the policy design and operational implementation of the Payment.

5.2 Summary table of costs and benefits of the preferred approach

| Affected parties (identify) | Comment: nature of cost or benefit (eg, ongoing, one-off), evidence and assumption (eg, compliance rates), risks | Impact $m present value where appropriate, for monetised impacts; high, medium or low for non-monetised impacts |

Evidence certainty (High, medium or low) |

| Additional costs of proposed approach compared to taking no action | |||

| Regulated parties (businesses) | Administrative costs of application and navigating more complex financial support environment | Marginal; not possible to quantify. | High |

| Regulators | Operational funding required for Inland Revenue | Uncertain; depends on nature of resurgence event. | High |

| Wider government | Increased complexity of business support landscape across government | Fiscal cost dependent on nature of outbreak. $320m estimated for AL2 nationally; $400m if AL3 nationally. | Medium |

| Other parties | |||

| Total Monetised Cost | Uncertain (see above) | High | |

| Non-monetised costs | Low | Medium | |

| Expected benefits of proposed approach compared to taking no action | |||

| Regulated parties | Support firms to pay fixed costs if they are struggling to do so as a result of escalated Alert Levels | The lesser of:

|

High |

| Regulators | Can contribute to improved tax morale. Also can improve tax compliance by bringing more people into the tax net. | Not possible to quantify. | |

| Wider government | Benefits to the long-term public finances from mitigating scarring effects of reduced demand | Uncertain; depends on nature of resurgence event. | High |

| Other parties | |||

| Total Monetised Benefit | Uncertain (see calculations in above box). | ||

| Non-monetised benefits | High | Uncertain | |

5.3 What other impacts is this approach likely to have?

- Other likely impacts which cannot be included in the table above, eg, because they cannot readily be assigned to a specific stakeholder group, or they cannot clearly be described as costs or benefits

- Potential risks and uncertainties

The counterfactual of not providing this support is unknown. However, the analysis sighted in this report indicates that the scarring effects attached to the risks of not cushioning the blow could be significant, with distributional consequences. We therefore judge that the provision of the RSP has potential to support the social license and capital needed to maintain a robust public health response, for the benefit of all New Zealanders.

SECTION 6: IMPLEMENTATION AND OPERATION

6.1 How will the new arrangements work in practice?

- When will the arrangements come into effect? Does this allow sufficient preparation time for regulated parties?

- How could the preferred option be given effect? E.g.,

- legislative vehicle

- communications

- transitional arrangements.

The RSP will be given effect through amendments to the Tax Administration Act 1994, scheduled to be introduced in February 2021.

The RSP was announced on 15 December 2020 and information on eligibility is available on a range of government websites. Cabinet has agreed retrospective payments will be possible in the event there is a resurgence prior to the application opening date, and subject to the legislation being passed.

In addition, engagement with key business groups including those representing Māori and Pasifika businesses will be pursued in order to ensure a maximum number of firms are aware of the support available.

Inland Revenue will be responsible for the ongoing operation and enforcement of the RSP.

Have the responsible parties confirmed, or identified any concerns with their ability to implement it in a manner consistent with the Government’s ‘Expectations for regulatory stewardship by government agencies’? See https://treasury.govt.nz/information-and-services/regulation/regulatory-stewardship/good-regulatory-practice

Inland Revenue has not identified any concerns with its ability to implement the new arrangements.

How will other agencies with a substantive interest in the relevant regulatory system or stakeholders be involved in the implementation and/or operation?

Design decisions have been delegated by Cabinet to relevant Joint Ministers, including the Minister of Finance, Minister of Revenue, and Minister for Small Business. Interdependencies with complementary support programmes such as the Wage Subsidy are regularly under review by the Treasury, IR and MSD.

6.2 What are the implementation risks?

- What issues concerning implementation have been raised through consultation and how will these be addressed?

- What are the underlying assumptions or uncertainties, for example about stakeholder motivations and capabilities?

- How will risks be mitigated?

Compressed timelines create delivery and communications risks, which could lead to:

- payments reaching the wrong businesses at an unnecessary fiscal cost;

- damaging the social capital that is critical for the success of the COVID-19 public health strategy;

- business confusion around the access to the scheme, meaning firms may lose out on support they are entitled to.

The main mitigations we have undertaken include:

- to agree, via Joint Ministers and Cabinet, detailed design rules in order to enable Inland Revenue to build the scheme at pace with as much certainty as possible;

- a series of measures to boost the integrity of the scheme and minimise gaming risks;

- taking a co-ordinated cross-Government approach to communications;

- engaging with external business stakeholders to inform the design of the scheme and promote its availability, ensuring the widest audiences are reached; and

- re-use of components developed for the SBCS as a way to meet challenging system delivery timeframes.

SECTION 7: MONITORING, EVALUATION AND REVIEW

7.1 How will the impact of the new arrangements be monitored?

- How will you know whether the impacts anticipated actually materialise?

- System-level monitoring and evaluation

- Are there already monitoring and evaluation provisions in place for the system as a whole (ie, the broader legislation within which this arrangement sits)? If so, what are they?

- Are data on system-level impacts already being collected?

- Are data on implementation and operational issues, including enforcement already being collected?

- New data collection?

- Will you need to collect extra data that is not already being collected? Please specify.

As with the wage subsidies, SBCS, and COVID-19 Income Relief Payment (CIRP), detailed data will be collected by the implementation agency (IR) on the uptake of the scheme. This will capture and allow government to evaluate outputs of the scheme. Information systems at IR are capable of this data collection.

Evaluation of outcomes will be imperfect, given the radical uncertainty that surrounds any resurgence event and the absence of any suitable counterfactual. In line with the objectives of the scheme and analysis that lead to its inception, we expect to minimise the erosion of firm balance sheets during a resurgence event, and ultimately prevent some insolvencies amongst viable firms that would otherwise take place. While we can assess balance sheet resilience quantitatively, much of this evaluation will be through engagement with business.

7.2 When and how will the new arrangements be reviewed?

- How will the arrangements be reviewed? How often will this happen and by whom will it be done? If there are no plans for review, state so and explain why.

- What sort of results (that may become apparent from the monitoring or feedback) might prompt an earlier review of this legislation?

- What opportunities will stakeholders have to raise concerns?

A review of the system will depend on whether it is activated. Subject to that, the operation of the scheme will be reviewed regularly based on user feedback and system metrics.

Monitoring of uptake and engagement will be undertaken in the event that the payment is activated as part of the broader monitoring of the economic situation.

If required, a review of any policy settings would be co-led by Treasury and Inland Revenue.