Employee share schemes

- Overview

- General issues

- Issue: Support for reforms

- Issue: Proposals increase complexity and uncertainty

- Issue: The policy framework is fundamentally flawed

- Issue: Employee share schemes are a valuable economic tool and the rules should not discourage their use

- Issue: Proposals result in double taxation

- Issue: Issues with consultation process

- Issue: Additional guidance on share valuation

- Income tax treatment of employees

- Issue: Clarification of terms used in Bill

- Issue: The definition of employee share scheme is too wide

- Issue: The proposals result in tax on capital gains

- Issue: Should impose fringe benefit tax on any downside risk protection

- Issue: The proposals are not a neutral framework for taxing income

- Issue: Future employment conditions should not delay the taxing point

- Issue: Effect of proposals on small and medium enterprises

- Issue: There is a lack of certainty under the proposals

- Issue: There should be an allowance for black-out periods and other sale restrictions

- Issue: Clarification of “bad leaver” exclusion

- Issue: Social policy and compliance cost implications

- Issue: Support for apportionment rule

- Issue: The apportionment rule should be extended to all remuneration

- Deductions for employers

- Issue: Support for the proposal

- Issue: Employer should be able to claim a deduction for actual costs

- Issue: Deduction proposal is practically unworkable

- Issue: Clarification of deduction formula required

- Issue: Bill should confirm that costs of setting up an employee share scheme are deductible

- Issue: Clarification as to timing of deduction

- Issue: Deductions will be fiscally costly to the Government

- Issue: Financial reporting adjustments will be required

- Exempt schemes

- Issue: Support retaining and modernising schemes

- Issue: Support for repeal of the notional 10% interest deduction

- Issue: Support for the increased threshold for amount that can be spent purchasing shares

- Issue: The threshold should be regularly reviewed in future

- Issue: The threshold should be higher

- Issue: There should be no limit on the minimum purchase price if an employee is required to buy shares

- Issue: Share purchase schemes should be renamed “exempt schemes” in the legislation

- Issue: Loans to employee should not have a minimum repayment schedule

- Issue: Can payment by “regular instalment” include regular purchase of parcels of shares?

- Issue: Support the reduction of eligible employees participating from all to 90 percent

- Issue: Support requirement to notify Commissioner of Inland Revenue (CIR) of scheme rather than request CIR approval

- Issue: Support the removal of the trustee requirement

- Issue: Support removing the deduction as the benefit is exempt

- Issue: Do not support removing the deduction for providing exempt benefits

- Issue: Deductions should not be denied from date of introduction of the Bill

- Issue: Period of restriction should be clarified

- Issue: Employers should report annually in respect of exempt schemes

- Issue: Clarification that employees in existing schemes can benefit from increased limits under the new rules

- Issue: Do existing exempt schemes have to notify CIR when grants are made?

- Issue: Deductibility of set-up costs

- Available subscribed capital

- Employee share scheme trusts

- Transitional rules

- Miscellaneous technical issues

OVERVIEW

Clauses 7, 10, 11, 12, 14, 23, 25, 28, 31, 41, 42, 60, 70, 74, 172(12), (13), (16), (19), (37), (43), (46), (50), (57), (58), (59), (60), (61), (67) and 248

Employee share schemes are arrangements for companies to provide shares and share options to their employees. They are increasingly an important form of employee remuneration in New Zealand and internationally. Although the design and the accounting treatment of these plans have evolved considerably over recent decades, the tax rules applying to them in New Zealand have not been comprehensively reviewed during that period and are now out of date.

Recently a number of problems with these rules have emerged, primarily in three areas:

- complex arrangements allow taxable labour income to be converted into tax-free capital gains;

- there is a lack of an employer deduction for the provision of employee share scheme benefits in some circumstances; and

- the rules and thresholds relating to tax-exempt widely-offered employee share schemes are out-dated and need review.

New core rules

The Bill proposes new core rules for determining the amount and time of derivation of income and incurring of expenditure under an employee share scheme. The objective of the proposals is neutral tax treatment of employee share scheme benefits. That is, to the extent possible, the tax position of both the employer and the employee should be the same whether remuneration for labour is paid in cash or shares. This will ensure that employee share schemes cannot be structured to reduce the tax payable in respect of these arrangements, as compared to an equivalent cash salary or other more straight-forward employee share schemes.

Generally these rules will apply to benefits where the taxing point under current law has not occurred before the day six months after the enactment of the Bill.

Income tax treatment of employees’ employee share scheme benefits

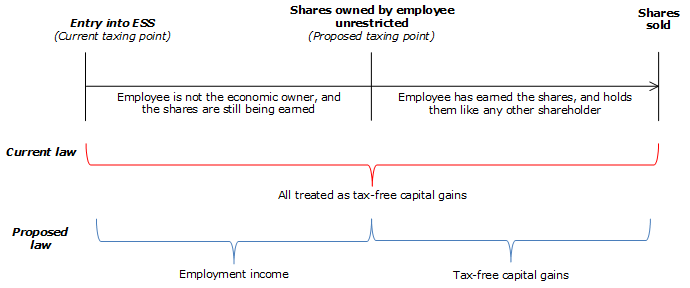

In essence, the provisions in the Bill redraw the line – for certain arrangements – which determines when an employee is treated as having earned shares under an employee share scheme (at which point they are taxable on the shares’ value), and after which they hold the shares like any other shareholder.

Source: SVG version

Like any other form of income, in straight-forward cases income received by an employee in the form of shares is not taxable until it is earned – that is, until the employee has performed all services and satisfied all conditions necessary for them to be fully entitled to the shares – at this point they have full ownership and control of the shares. The amount of income is the value of the shares at that time. So, changes in the value of the shares occurring before that time will affect the employee’s income.

Once the employee has earned the shares and holds them like any other shareholder, increases in value will generally be tax-free capital gains.

This is the longstanding tax treatment of straight-forward share schemes (that do not use trusts) and options.

It is also the same as the tax treatment of any other non-cash payment for services. For example, an employee could be paid in gold bars or a boat. The market value of that non-cash asset is taxable as employment income when the employee earns it, thereafter, fluctuations in its value will generally be on capital account.

The Bill proposes changes to the way employees are taxed when shares are given to a trustee to hold for an employee until certain conditions are met.

In these arrangements, while the shares are held by the trustee, the employee is neither the legal owner, nor the full economic owner of the shares (even if they have certain rights, such as to receive dividends). Legal title, and the ability to trade in the shares, like any other shareholder, is not transferred to the employee until they meet employment conditions – that is, until they earn the shares. If the employee does not meet those conditions, the shares can be transferred back to the company by the trustee, or used to provide a benefit to another employee.

Under current law, the employee is nevertheless taxed when the shares are transferred to the trustee (albeit that many arrangements eliminate tax at this point by allowing the employee to pay full market value for the shares using a limited recourse loan, which is only repaid in certain circumstances). The Bill would change this, so that the employee is taxed when the shares are transferred by the trustee to the employee, and the employee is the economic owner. This is the appropriate taxing point. After that point, the employee is treated like any other shareholder, and can derive tax-free capital gains.

The Bill also proposes to change the law in cases beyond those involving a transfer of shares to a trustee. However, the proposals are carefully targeted – following consultation – to ensure they do not defer the taxing point past the time when the shareholder really is the economic owner. In particular, the provisions in the Bill will not apply where the employee has to sell the shares back to the company for market value[12] if they leave the company. The proposals would therefore not prevent any gain on a sale of the shares being treated as a capital gain in this case.

Employers’ deductions

The Bill also proposes a new deduction rule for employers providing employee share scheme benefits to employees.

The Bill proposes allowing the employer a tax deduction for the amount of the employee’s income, at the same time as the employee is taxable, in order to align the tax treatment of providing employee share scheme benefits with the tax treatment of paying other types of employment income.

When an employer pays for an employee’s services – whether in shares or cash – there is a cost that should be reflected in the calculation of the company’s income.

Until the mid-2000s, financial accounting standards did not require this cost to be recognised in the company’s financial accounts and this enabled companies to artificially inflate their profits. The relevant accounting standards now recognise the economic cost of issuing shares for services and this amount is treated as an expense of the company in calculating its income.

The provisions in the Bill ensure that tax law also recognises this economic cost. At the time the company gives the employee a valuable asset (the shares) in exchange for their services, the employee is better off by an amount equal to the value of those shares, and the other owners of the company are correspondingly worse off.

The argument can be made that the provision of the shares leaves the company itself no worse off, since it has not had to part with any property. However, it is clear that there is an economic cost to the other shareholders, since their interest in the company has been diluted. Under our corporate tax system, this deduction cannot be claimed by the shareholders, but it is appropriate for it to be claimed by the company.

This is exactly the same tax treatment as for cash salary which the employee uses to subscribe for shares at market value.

Widely-offered exempt schemes

The Bill also proposes a simplified set of rules for certain widely-offered employee share schemes (commonly referred to as “exempt schemes”), with a greater level of exempt benefits able to be provided and more flexibility in the design of these schemes.

The Bill aims to clarify that employers offering exempt benefits will not be entitled to a deduction for the cost of providing those benefits.

The retention of the tax exemption for exempt schemes departs somewhat from the objective of neutral tax treatment for all remuneration, but is justified on compliance cost grounds.

Consequential and technical amendments

The Bill also proposes a number of consequential and miscellaneous changes to the employee share scheme rules and provides transitional arrangements for existing schemes.

GENERAL ISSUES

Issue: Support for reforms

Submission

(Chapman Tripp, Roger Wallis, KPMG, Chartered Accountants Australia and New Zealand)

Chapman Tripp and Roger Wallis support the measures in the Bill on the basis they simplify and clarify the treatment of employee share schemes. Roger Wallis also supports the objective of aligning the tax treatment of share and option schemes with other forms of employment income.

KPMG welcomes the clarification of the law following the issue of a Revenue Alert regarding employee shares schemes.

Chartered Accountants Australia and New Zealand supports the objective of the proposals to modernise and rationalise the tax treatment of employee share schemes.

Recommendation

That the submitters’ support be noted.

Issue: Proposals increase complexity and uncertainty

Submission

(Russell McVeagh, Spark, Olivershaw)

The proposals increase uncertainty and complexity, and should not proceed.

Russell McVeagh submitted that the proposed rules will impose higher compliance costs, which will disincentivise employee share schemes. They also submitted that the proposals appear broadly fiscally neutral, as the amount of the employer’s deduction is equal to the employee’s taxable income. A wholesale change to the tax rules for employee share schemes is therefore unnecessary.

Spark submitted that the increased complexity is not warranted for the sake of a five percent differential (between the company tax rate of 28% and the top marginal rate of 33%).

Comment

Like all significant tax policy proposals the proposals have been subject to full public consultation. Issues such as ambiguity, complexity and compliance costs were raised and dealt with to the extent possible as part of that process.

The proposed rules are simple for simple transactions. For complex arrangements that involve loans, bonuses, trusts or intercompany recharges, then the rules are necessarily more complex.

It is true that, for some arrangements, the current rules are more certain, because they apply a very legalistic rule to determine when employee share scheme benefits are taxable – the time that the employee (or a trustee on their behalf) acquires the shares.

However, experience has shown that this rule can be used to produce results which are not appropriate for the integrity of the tax system. In particular, it allows employers to provide employees with what are effectively employee share options and cash bonuses with no or minimal tax to pay. This has led to the general anti-avoidance provision being applied to some schemes. Applying the general anti-avoidance rule inevitably leads to uncertainty, and therefore to law which involves greater compliance and administrative costs because it requires careful analysis in every case and often resort to the courts.

The Bill contains a more substance-based test for determining when employee share scheme benefits are taxable. In the vast majority of cases, and given the usual level of Inland Revenue guidance, this test will be no more difficult to apply than the current test. Crucially, it will be more difficult for taxpayers to achieve unintended outcomes under the proposed test in the Bill, and therefore there will be much less need to rely on the general anti-avoidance rule.

Officials note that a number of submitters believe the changes will increase certainty.

Officials therefore do not agree that uncertainty would be increased to the point that the proposals should not proceed.

Officials do not agree that the proposals are revenue neutral (as submitted by Russell McVeagh). The package of measures is forecast to generate $30 million of revenue per annum once fully phased in.

Officials do not agree with the submission that the proposals should not proceed on the basis that there is at most only a five percent difference between the tax payable by an employee on an employee share benefit and the benefit of the tax deduction available to the employer for providing that benefit. By this rationale we would give up taxing employment income altogether, since the five percent differential is the case for cash salary and wages as well.

Taxing employee share schemes benefits, and employment income generally, ensures that:

- employees are taxed at the appropriate marginal rate; and

- income tax is paid when a company in tax loss or which is tax exempt makes a payment to an employee.

Including employee share schemes benefits is also relevant for measuring eligibility for income tested benefits and student loan repayments.

Officials note that tax rates do change from time to time, and the difference between the top marginal rate and the corporate rate may change in future.

Recommendation

That the submissions be declined.

Issue: The policy framework is fundamentally flawed

Submission

(Olivershaw, Corporate Taxpayers Group, Spark)

The assumption in the proposals is that cash and shares derived from employee share schemes are substantially the same and should be taxed in the same manner. However in reality, cash bonuses are not equivalent to share scheme awards.

Employees, when offered an amount of shares or an equivalent amount of cash, would almost always favour a cash award due to its greater liquidity. Cash bonuses are not directly comparable to a share award unless the bonus amount is linked to the share price (for example, a phantom share scheme).

Comment

Officials do not agree with the submission that the framework for the Bill is fundamentally flawed.

Essentially, the Bill proposal rests on three pillars:

- Taxing employee share scheme benefits only when they have been earned.

- Taxing employee share scheme benefits in the same ways as other forms of remuneration (such as cash bonuses).

- Taxing share options, and arrangements like share options, only when and if the option is exercised.

While cash remuneration is obviously different in some respects to remuneration paid in shares (or to other fringe benefits, for that matter), none of the differences are meaningful for the purposes of the tax treatment. In particular, one form of remuneration should not have a tax advantage over the other. Otherwise, there is a tax incentive to pay people using share schemes, when it may be more economically efficient to simply pay them cash salary.

Recommendation

That the submission be declined.

Issue: Employee share schemes are a valuable economic tool and the rules should not discourage their use

Submission

(Corporate Taxpayers Group)

Employee share schemes are a valuable economic tool. The rules should not discourage their use.

Employee share schemes are an important employee remuneration tool and provide significant economic benefits to New Zealand more generally. Specifically, employee share schemes:

- assist with aligning employee and business interests; and

- build employee loyalty and encourage staff retention.

They also provide wider economic benefits through increased participation in capital markets, boosting savings and developing a financially literate population.

Comment

Officials agree that employee share schemes can be a valuable remuneration tool and their use should not be discouraged. The Bill does not discourage their use. It removes an avenue by which they can be unfairly advantaged, and also for some schemes removes an existing disincentive to their use (that is, the inability of the employer to claim a deduction).

While well-designed employee share schemes can achieve the outcomes identified by submitters, these benefits are largely enjoyed by the parties to the arrangement (that is, the employer and employee). Accordingly, there is no reason that employee shares schemes should enjoy preferential tax treatment as compared to other forms of remuneration.

Recommendation

That the submission be declined.

Issue: Proposals result in double taxation

Submission

(Olivershaw)

The proposals seem to result in double taxation of the same income when the gain in share value merely reflects increased and already taxed income of the company as the employee is also taxed on this gain.

Comment

Officials do not agree that the proposal results in double taxation. The submission overlooks the fact that the company will be entitled to a deduction equal to the employee’s income. There is no aggregate increase in income, simply a change in who is treated as earning it. A simple example illustrates this. Assume a company earns $100 (this is its only asset), and gives its employee 10 percent of the shares in the company. The employee will be taxable on $10 and the company will receive a $10 deduction. So the company will only be taxable on $90. Therefore there has been no double taxation with respect to the $10 of income received by the company.

Recommendation

That the submission be declined.

Issue: Issues with consultation process

Submission

(Corporate Taxpayers Group)

The process for consulting on this collection of policy changes has not been well coordinated, with additional proposals constantly being added outside of formal consultation processes. The Group strongly opposes the addition of any further “officials’ changes” to these rules through the Select Committee process.

Comment

Officials do not agree that the process has not been well co-ordinated. A function of public consultation is that issues are flushed out. As issues have emerged during the consultation process, officials have gone back to the private sector to consult on them. This is a natural and efficient means for addressing issues rather than as subsequent legislative amendments.

There have been two rounds of public consultation, with numerous workshops with interested parties.

After discussions with submitters, officials have decided not to recommend one particular change (relating to subordinated ordinary shares) through the Select Committee process, but instead to progress this issue separately, for possible inclusion on the Government’s tax policy work programme.

Recommendation

That officials’ response to the submitter’s comments be noted.

Issue: Additional guidance on share valuation

Submission

(EY)

EY would appreciate more guidance around how to value shares in an unlisted company at the share scheme taxing date.

Comment

Officials note that the Commissioner has recently released CS 17/01, providing guidance on the valuation of shares in both listed and unlisted companies. Taxpayers can seek amendments to this document if they are concerned about lack of guidance.

Recommendation

That officials’ response to submitter’s comments be noted.

INCOME TAX TREATMENT OF EMPLOYEES

Issue: Clarification of terms used in Bill

Clause 14

Submission

(Chapman Tripp, Olivershaw, KPMG, Russell McVeagh, Roger Wallis, EY)

More guidance is needed on the terms “no real risk” and “no commercial significance” (in proposed section CE 7B(1)(a) and 2(c)).

Proposed section CE 7B should contain examples clarifying the application of the “no real risk” test. (Chapman Tripp, Roger Wallis)

The term “no real risk” should be changed to “no significant risk” or “no material risk”. The term “no real commercial significance” should be changed to “no commercial significance”. (EY)

Comment

Officials agree that these terms should be further explained and examples should be provided in the legislation and following enactment, in a Tax Information Bulletin to illustrate their application.

Recommendation

That the submission be accepted.

Issue: The definition of employee share scheme is too wide

Clause 14

Submission

(Chapman Tripp, Olivershaw, KPMG, Russell McVeagh, Roger Wallis, EY)

Definition of “employee share scheme” is too wide and unintentionally capture share transfers that are gifts. For example, a mother gifts shares to daughter who is also an employee.

Arrangements referred to in proposed section CE 7(a)(i) and (ii) should be qualified with the statement “if the arrangement is connected to Person A’s employment or service”. Otherwise the definition could cover on-market transactions where someone buys shares in their (future/current/past) employer but it is entirely unrelated to their employment.

Comment

Officials agree with these submissions. In particular, the criterion in proposed section CE 7(a)(iii) of the employee share scheme definition – that the arrangement is connected to a person’s employment or service – should apply to all three subparagraphs in proposed section CE 7(a).

Recommendation

That the submission be accepted.

Issue: The proposals result in tax on capital gains

Clauses 11, 12 and 14

Submission

(Chartered Accountants Australia and New Zealand, Corporate Taxpayers Group, Olivershaw, Spark, KPMG, Russell McVeagh)

The existing rules draw an appropriate distinction between the employment income component and the capital gain or loss component of an employee share scheme benefit. The proposed rules would tax capital gains as employment income.

Value fluctuations in shares held on trust for an employee as part of an employee share scheme are a function of capital markets, not of anything the employer or employee does. Because the price changes are outside the control of the employee, these should not be taxed as employment income.

Egregious arrangements could be struck down by applying the GAAR and enacting specific anti-avoidance rules.

Comment

Officials do not agree that the current rules draw an appropriate line between income from employment and income from capital gains. This can be explained with a simple example. Under the current rules, if A’s employer promises to give her 100 shares in two years’ time if she remains employed, A is taxed on the value of the shares in two years’ time. If B is a beneficiary under an employee share scheme where the scheme trustee is given 100 shares now, on the basis that they will be transferred to B in two years’ time if they remain employed, B is taxed on the value of the shares when they are given to the trustee. This difference in treatment is not sensible, since the two employees are effectively in the same position.

Officials do not agree with the submission that because changes in the value of shares are outside an employee’s control, such changes should not be treated as employment income, but should instead be treated as capital gain or loss. Employment income is income given as a reward for services. The status of a payment as employment income has nothing to do with whether or not the amount of that payment can be controlled by the employee. For example, suppose an employee of a listed company is promised a cash bonus at the end of the year equal to the increase in the employer’s share price. Whether or not a bonus eventuates, and the amount if it does, may have little to do with the employee’s individual efforts, and much more to do with the workings of the capital markets. Nevertheless, no one would suggest that the cash bonus should not be taxed as employment income. Similarly, an employee can be paid for their services in other assets (for example, a gold bar or a boat) whose value is not determined by the employee’s individual efforts; nevertheless they are taxable on the value of the asset as it is labour income.

Recommendation

That the submission be declined.

Issue: Should impose fringe benefit tax on any downside risk protection

Clauses 11, 12 and 14

Submission

(Olivershaw)

If the problem is the tax-free benefit of downside risk protection to an employee under the current law, then the solution seems simple – to the extent the employer buys or arranges for the purchase of shares at more than their current market value, the difference should be taxed under the fringe benefit tax (FBT) rules.

Comment

The submitter suggests that the key tax policy problem is the current tax treatment where an employer provides protection from a fall in the shares’ value. They say this protection is a valuable benefit that currently goes untaxed. They suggest that any issues that arise with the current tax law in relation to employee share schemes would be solved if this benefit was subject to FBT. Officials do not agree with this viewpoint. This suggestion was raised by the submitter and thoroughly canvassed during consultation.

The way employers typically provide “downside protection” for employees is by providing an employee with a limited-recourse loan to buy the shares or a put option that allows the employee to sell the shares back to their employer at the price they paid for the shares. If the shares go down in value, the employer has to accept the shares back from the employee in full satisfaction of the loan or the employer must buy the shares back from the employee for the price the employee paid for them. Alternatively, in cases where the employee can keep the shares, the loan is forgiven/repaid by the company to the extent the share value is less than the loan balance. If the shares go up in value, the employee can pay off any outstanding loan (often funded by a bonus from the employer), and keep the shares.

The submitter’s suggestion is based on the proposition that the benefit being provided in this case by the employer is that when the shares are worth less than the loan (or the original purchase price, in the case of an employee who does not receive a loan to buy the shares), the employee is protected from that drop in value – either because, in the case of a loan to buy the shares, they can repay the loan by providing the shares to the employer or they are otherwise indemnified from the obligation to repay the loan to the extent the share value is less than the loan balance. Similarly, in a case where the employee does not have a loan to buy the shares, the employee is protected from the loss of their original investment as a result of the put option. The submitter’s suggestion would require FBT to be paid if the shares drop in value and the employee receives nothing from the arrangement – that is, the shares revert to the employer and the loan is unwound, or the employee keeps shares that are ultimately worth what they paid for them (there is no net benefit).

Conversely, if the shares go up in value and the employee gets to keep the shares which are worth more than they paid for them, then the submitter says they would not be taxable on this benefit. Therefore the submitter’s suggestion would tax the employee if they received nothing from the share scheme on a net basis, but fail to tax them if they actually received a benefit.

As well as being conceptually incorrect, this proposal is counterintuitive and, in our view, would be completely unpalatable to the vast majority of share scheme participants. It taxes when an employee ends up with nothing, while imposing no tax where a person receives valuable share benefits for working for a company.

If people are taxed when no benefit has accrued, this suggestion would actually have the effect of discouraging the use of employee share schemes.

Additionally, as a matter of principle, if an employee holds both the shares and a put option that protects them from a fall in the value of the shares (and these two assets must always be held together as part of an employment arrangement), this is economically equivalent to holding a call option over the shares (plus holding a zero coupon bond equal to the purchase price of the shares).[13] This is because in both cases, the employee is entitled to the upside in the share price movement, without any exposure to the downside in the share price movement. The longstanding tax treatment of call options is to tax these on exercise – this is consistent with the proposals contained in the Bill in relation to downside protection arrangements such as put options and loan forgiveness. If the arrangements in questions were taxed in the way the submitter’s suggests, then two economically equivalent transactions would be taxed quite differently. This outcome is inefficient and not consistent with good tax policy.

As a secondary comment, officials note that recent reforms allowing employees to pay PAYE on employee share scheme benefits looked at FBT as an alternative mechanism and submitters were overwhelmingly against this option (as was Inland Revenue). So the suggestions that FBT should be payable in the circumstances described above is unlikely to be favourably viewed by companies offering employee share schemes.

Recommendation

That the submission be declined.

Issue: The proposals are not a neutral framework for taxing income

Clauses 11, 12 and 14

Submission

(Chartered Accountants Australia and New Zealand)

The proposals are not a neutral framework for taxing income. Cash remuneration is taxed at the time of receipt rather than at the time the services are performed.

Consider an employee who is paid monthly and receives an annual salary of $120,000. Payment is made on the 15th of the month. Payment is for past services (1st – 15th) and for future services (16th to the end of the month).

The employee will be taxed on the total $10,000 when it is received each month, regardless of the fact that some of the services are not yet performed.

For consistency and fairness, the time the shares are received under an employee share scheme should be the taxing date.

Comment

Officials do not agree that the example of cash remuneration paid in the middle of the month is relevant to the proposals in the Bill. In this case, under the provisions in the Bill, the shares would be taxed at their value on the 15th of the month when the shares were received, so long as there was no requirement for their return if the employee did not remain employed for the next two weeks.

If the example is modified, so that the shares are not able to be sold by the employee until the end of the month, and must be returned if the employee does not remain employed until the end of the month, then the shares would be taxed at their value at the end of the month. Officials believe that is the correct outcome.

In the submitter’s example, the employee has the cash at their disposal and may spend it as they wish – even before they have provided all the services required to earn it. Presumably, if they spend the money and then do not provide the services, the employer could require them to pay it back. Nevertheless, until this time the employee has had the cash at their complete disposal. This differs from employee share scheme arrangements where shares are transferred to a trustee for an employee subject to the satisfaction of certain conditions, as the shares are not fully at the disposal of the employees and in the majority of cases are not even received by them. The shares are held in trust.

A more accurate comparison in respect of the employee share scheme proposals, would be a situation where cash salary is put in a trust account for the employee and only released, and able to be spent, by the employee when they have provided the services to earn the cash. In this case, the cash would not be “received” or taxable until it has been released from the trust. In this comparable case, the taxing point is the same for both the cash and the shares under the employee share scheme proposals.

In an extreme (and commercially unusual case), if the shares were given to the employee at their complete and unrestricted disposal, but on the condition that if the employee did not perform services over a specified period of time they would have to deliver an equivalent parcel of shares back to the employer, then this would be a comparable scenario to the cash salary example the submitter sets out above. In this case, the employee could sell the shares and spend the proceeds before they have performed the services needed to earn the shares, but they take the risk that they may have to deliver those shares back to the employer and – if they have sold them in the interim – they would have to buy them back on market (if this is even possible). This is similar to short selling and would not make sense in an employee share scheme context, because employees would be better off if their employer’s shares drop in value (rather than increase in value) as they can sell the shares at a high price, then buy them back at a low price and pocket the difference. Thus such an arrangement creates the opposite incentives that an employee share scheme seeks to create (that is, the incentive to increase the value of an employer’s shares). Accordingly, officials do not believe this example would occur in practice.

In addition – in relation to the cash payment, it is immaterial whether the situation is analysed as giving rise to income of $10,000 on the 15th of the month, or $5,000 on the 15th and $5,000 on the 30th. The same amount is taxable, at almost exactly the same time. For convenience, and because most tax from employment income is collected by way of withholding, the law focuses on when cash is paid. However, in relation to employee share scheme benefits, where values can change and time frames are often much longer, more care needs to be taken to define the time of derivation.

In view of these various scenarios, officials believe that the proposals do provide a neutral framework for taxing employee share schemes compared to an equivalent cash transaction.

Recommendation

That the submission be declined.

Issue: Future employment conditions should not delay the taxing point

Clauses 11, 12 and 14

Submission

(Chartered Accountants Australia and New Zealand)

Future employment conditions should not delay the taxing point. They should be factored into valuation.

Comment

Officials do not agree with the submission that shares transferred to an employee (or trustee) subject to return if employment conditions are not met should be taxed when provided at a discounted value. For example, when an employee is offered a cash bonus payable in one year if the employee remains employed for that time, there is no suggestion that the cash bonus should be taxed at the time it is offered, with a discount for the risk that the employee will not be employed in one year. The bonus is taxed when it is paid, in one year’s time. The position should be the same with shares. Waiting to tax employment income until employment conditions are met is both orthodox and sensible.

It would also be practically very difficult for the parties to the employee share scheme to determine an appropriate valuation to take account of specific employment related condition, and consequently compliance cost intensive.

Recommendation

That the submission be declined.

Issue: Effect of proposals on small and medium enterprises

Clauses 11, 12 and 14

Submission

(Olivershaw)

The proposals have an unknown effect on small and medium enterprises (SMEs). If employees have to sell their shares back when they leave employment they will hold them on revenue account.

Comment

Through two rounds of public consultation, the effect of the proposals on SMEs has been explored. As a result, certain arrangements have been excluded from the ambit of the proposed rules. For example, officials note that shares will not be “held on revenue account” (that is, the taxing date will not be deferred) merely because there is an obligation on an employee to sell those shares to their employer for an amount intended to be the shares’ market value when they leave employment (which officials understand is usual commercial practice in this case) (see proposed section CE 7B(2)(a) in clause 14).

Recommendation

That the submission be declined.

Issue: There is a lack of certainty under the proposals

Clauses 11, 12 and 14

Submission

(Spark)

When the participant enters into the share scheme, the employer and participant will not know what the ultimate income and/or deductions will be. A lack of certainty is a poor outcome for both the employer and share scheme participant.

This uncertainty is highly undesirable for any business because the employee’s income is effectively uncapped based on factors outside the control of the employer and employee. If the employer has agreed to fund the tax liability, this exposes the employer to an uncertain tax Bill in addition to complex compliance. Commercially, it would be unusual for a business to enter into such an uncertain arrangement.

For the participant, while it may be possible to arrange the scheme in a way that they can sell some shares to meet the tax cost, it is possible that they are restricted from selling these shares due to blackout periods or insider trading restrictions. A scheme that requires participants to sell shares is less likely to be attractive to participants and shareholders who would prefer that employees retain shares in the company to have some “skin in the game”.

Comment

Some submitters are concerned that the effect of the proposals is that the amount of taxable income from an employee share scheme is not known at the outset, that is, when the employee share scheme benefits are offered to the employee on some kind of conditional basis.

Officials observe that:

- this seems an inevitable result of the commercial transaction, where the benefit provided is unconditional ownership of shares at a future point in time. The value of the shares is not known when the benefit is offered or when the shares are transferred to the trust. If the taxable income were known at the outset, that would suggest that the tax treatment is not matching the economic reality;

- many companies and employees already cope with exactly this uncertainty, for example those offering or receiving benefits under share option schemes or simple conditional share schemes;

- employers, when designing their schemes, can ensure they have the ability to meet any tax liability by issuing shares (either new shares or treasury stock) to fund any tax liability;

- if employers do not want employees to sell their shares to pay tax on employee share scheme benefits, the employers can pay PAYE on the share benefits, or provide the employee with an additional cash bonus; and

- schemes can generally be designed so that vesting occurs outside no-trading periods.

With respect to the “skin in the game” submission, even if the employee sells all of the shares required to pay the tax, they will still be left with 67 percent of the shares, that is, they will still have considerable skin in the game. To ensure that any “skin in the game” requirement can easily be met, employers can require the employee to retain a certain number of the shares provided.

Recommendation

That the submission be declined.

Issue: There should be an allowance for black-out periods and other sale restrictions

Clauses 11, 12 and 14

Submission

(Spark, Russell McVeagh)

The rules should provide an allowance for “blackout periods” (that is, periods of time when employees are unable to trade their listed shares because of insider trading or other restrictions). That is, the taxing point for these shares should be deferred until the blackout period ends and employees can sell their shares.

Employees of unlisted companies may be prohibited from selling their shares by the company’s constitution or shareholder agreement.

Comment

Officials note the suggestion that the taxing point should be further deferred is contrary to other submissions by the same submitters that the taxing point should not be deferred. These submitters have also argued that shares should be taxed when provided to a trustee who holds them on behalf of an employee, even where the shares may not be able to be sold for some years.

Given that blackout periods are generally short, and that schemes can generally be designed so that shares vest outside that period, officials do not believe it is necessary for the rules to cater for blackout periods.

In terms of the observation that employees of unlisted companies may be prohibited from selling their shares by the company’s constitution or shareholder agreement, officials do not believe this is directly relevant to the proposals in the Bill. These restrictions exist as separate commercial arrangements, unconnected with the employee share scheme. To the extent this presents a cashflow (or other) issue, this issue exists under current law (and in relation to other non-cash income). Under existing law, an employee who is given shares in their employer which the person is unable to sell is taxable on those shares when they are acquired by the person or a trustee.

Under the proposal, the employee will be taxable once the shares vest in the person (broadly speaking). In either case, the employee has to pay tax on the value of shares which they are unable to sell. Under the Bill, the tax will be paid at a point which generally speaking is closer to when the shares are able to be sold.

Inability to sell shares does not mean that the employee has received no value or that they should not be taxed. The employee will be entitled to dividends and any increase in the shares’ value over time.

Recommendation

That the submission be declined.

Issue: Clarification of “bad leaver” exclusion

Clauses 11, 12 and 14

Submission

(EY)

If the desired policy outcome is that the risk of being a “bad leaver” should not affect the share scheme taxing date, the legislation should specifically say this.

Comment

Officials agree with this submission. An example will be provided in the legislation to clarify this.

Recommendation

That the submission be accepted.

Issue: Social policy and compliance cost implications

Clauses 11, 12 and 14

Submission

(Spark)

The proposals will complicate participants’ income tax compliance and may require them to interact with Inland Revenue to handle various social policy obligations. In addition, the uncertain final tax outcome may also drive the participant into the complexity of the provisional tax rules (which the submitter states should be viewed as being anathema for employment remuneration).

Trustees will be required to play a more active role in facilitating the sale of shares on behalf of participants in order to meet the participants’ tax and social policy obligations.

The business will be required to calculate the income/deduction and advise the employee of this.

Comment

The tax treatment proposed in the Bill aligns with the longstanding treatment of share options, which have been successfully used by a number of companies for many years. Offering employee share schemes (or any other form of non-cash remuneration) generally involves slightly higher compliance costs than simply paying an employee in cash. Notwithstanding this, it is important that employee share scheme benefits are taken into account in working out social policy entitlements, so that people receiving employee share schemes do not have any advantage compared to someone receiving cash salary.

Officials agree that under longstanding current law, employees who receive employee share scheme benefits of more than approximately $7,500 per annum will be subject to provisional tax, although they will not be subject to use-of-money interest unless they have benefits that exceed approximately $180,000 per annum.

While it would be possible to exclude employee share scheme benefits from the application of provisional tax, there is an equity issue with other types of one-off income which would continue to have provisional tax implications. It is more appropriate to consider this as part of the continuing business tax stream of Inland Revenue’s business transformation.

In addition, employers have recently been given the option of paying PAYE which ensures that employees are not subject to the provisional tax regime and will reduce compliance costs for their employees more generally – particularly in respect of social policy entitlements.

Currently, employee share scheme benefits (whether subject to elective PAYE or not) are included as income for the purposes of Working for Families, student loan repayments and child support. They are excluded for KiwiSaver and ACC levies.

For Working for Families, an employee can call Inland Revenue to advise they have received the employee share scheme benefit and Working for Families will be adjusted accordingly.

Child support is calculated based on previous years’ earnings. So if an employee receives an employee share scheme benefit, it will be taken into account for the employee’s next years’ obligations, but will not affect the current year obligations.

If PAYE is withheld from an employee share scheme benefit, then student loan repayments will be automatically withheld as well. If the employer has not elected to pay PAYE, then there may be an under-deduction and the recipient might have to make extra repayments at the end of the year.

In terms of the trustee’s involvement in managing the tax obligations of an employee share scheme, there is no requirement that the trustee do this. Some employers choose to engage a trustee or registry service to assist participants to sell shares to meet tax obligations, but – again – this is something many trustees already do under current law.

With respect to the comment that employers will be required to calculate the income/deduction and advise the employee of this – employers already have to do this under existing law to comply with their PAYE and information disclosure requirements. The measures contained in the Bill do not impose any additional requirements in this respect. In particular, there is nothing in the proposed measures in the Bill that would require an employer to tell an employee what figures the employer has used in their employer monthly schedule (EMS) in respect of that employee’s employee share scheme benefit. However, employers may choose to do this as a matter of good practice.

Recommendation

That the submission be declined.

Issue: Support for apportionment rule

Clause 12

Submission

(KPMG)

KPMG supports the apportionment rule in relation to employee share scheme income earned partly offshore and partly in New Zealand.

Recommendation

That the submitter’s support be noted.

Issue: The apportionment rule should be extended to all remuneration

Clause 12

Submission

(PwC)

There is no equivalent rule in the Income Tax Act 2007 for cash settled remuneration which apportions income accrued while the employee was a non-resident, as the Bill proposes for employee share scheme income. An equivalent apportionment formula should be introduced for cash settled remuneration.

Comment

Employee share scheme benefits often relate to the provision of services over an extended period. This is not generally the case for cash remuneration. Accordingly, officials do not see any compelling reason for a similar apportionment formula for cash remuneration.

Recommendation

That the submission be declined.

DEDUCTIONS FOR EMPLOYERS

Issue: Support for the proposal

Clauses 23 and 41

Submission

(Corporate Taxpayers Group, Chartered Accountants Australia and New Zealand, KPMG)

Corporate Taxpayers Group and Chartered Accountants Australia and New Zealand support the deduction proposal in principle, subject to specific submissions on the timing and amount of the deduction.

KPMG strongly supports the proposal to provide a deduction and to align it with income derived by an employee. This ensures consistency between treatment of employee share schemes and other remuneration.

Recommendation

That the submitters’ support be noted.

Issue: Employer should be able to claim a deduction for actual costs

Clause 41

Submission

(ANZ, Corporate Taxpayers Group, Russell McVeagh, EY, Chartered Accountants Australia and New Zealand)

A deduction by reference to an employee’s income ignores the cash cost to the employer of providing an employee share scheme benefit. The deduction should be for the cash cost in the case of a recharge or payment to a trust. The proposal may overtax.

For example, Parent Co issues 700 shares worth $3 each to an employee of Employer Co. Parent Co charges Employer Co $2,100 for the shares. The scheme’s taxing date is at the end of Year 1, at which time the market value of the shares is $2 each. Based on the proposed rule, Employer Co has a deduction for $1,400 at the end of Year 1 although it actually paid $2,100 in Year 0.

Corporate Taxpayers Group and EY submit that the deduction available to the employer should be the greater of:

- the actual costs incurred by the employer to provide the shares to the employee. This would include the cost of acquiring the shares/reimbursing the parent company as well as associated transaction costs; and

- the amount of income arising to the employee plus associated transaction costs.

Actual cash costs should be immediately deductible. Any further cost (when the employee receives income) should be deductible at that point.

Comment

Contrary to views expressed in some submissions, under current law a company is not allowed a deduction for the cost of acquiring shares which are subsequently provided to employees. Certain arrangements have been developed to achieve a tax deduction – most commonly:

- settlement of funds on an interposed trust to enable the trust to buy the company’s shares for the purpose of the employee share scheme; and

- payments to a parent company to procure the parent company to provide shares to the subsidiary’s employees.

Officials would like to clarify the economic nature of share repurchases by trusts and parent reimbursements in the context of employee share schemes. Submitters see share repurchase and parent reimbursement payments as deductible costs of remuneration, whereas from an economic perspective they are payments in respect of the company’s share capital – the company is dealing in its own shares. The remuneration expense does not arise until such time as the shares are actually provided to the employee.

Share repurchases

Money paid by a company to purchase its own shares is a return of funds to its shareholders. Generally it is treated by the company as either a return of paid up capital, or a distribution of retained earnings. If the shares are purchased as treasury stock and reissued within 12 months, then for tax purposes the transaction is disregarded altogether by the company. In either case the tax effect of the purchase of the shares is that they no longer exist. Under current law, there is no tax deduction in respect of this transaction. Companies have been achieving a deduction by interposing a trust that buys and holds the shares until they are allocated. The use of the trust (which is generally controlled by the company through its directions to the trustee) does not fundamentally change the nature of the transaction – it is a transaction involving the company purchasing its own shares to be held effectively as treasury stock until such time as they are allocated.

This tax treatment of a share purchase by the issuing company applies whether the shares are purchased in order to later provide them to an employee, or for some other reason. Accordingly, it is not appropriate from a policy perspective to treat the amount paid to repurchase the shares as a deductible expense, even if the shares are later issued to an employee. From a policy perspective, the shares purchased by the company are destroyed, and the shares issued are not the same shares as those acquired. This is also the effect of current law.

Under the Bill, the deductible expense arises when shares are issued to an employee in satisfaction of employee share scheme obligations. The expense is the dilution of the other shareholders’ interests in the company. The amount of the expense is not affected by whether the shares issued are new shares, or existing shares acquired on market.

Accordingly, officials do not agree with the submission that the cost of acquiring shares from existing shareholders for the purpose of satisfying employee share scheme obligations is a deductible expense to the company. It is either a return of capital, a distribution of earnings, or disregarded altogether.

Reimbursement paid by employer to share issuer

Under current law an employer company is permitted a deduction for reimbursement paid to another group company for issuing shares. From a policy perspective, the amount of an employer’s deduction for issuing shares under an employee share scheme should be equal to the employee’s income. This is true whether the shares are in the employer or its parent. The value of what has been provided to the employee is the same, and the cost to the group as a whole is the same. If the employer is not required to make any payment to its parent in reimbursement, or is required to make a payment that is less than the value of the shares, that is equivalent to a contribution of capital by the parent to the employer. If the employer is required to make a greater payment, that is equivalent to a distribution by the employer. The potential tax consequences of a distribution can be avoided by the employer agreeing to pay no more than the value of the shares at the taxing point. If the reimbursement payment does exceed the share value, the Bill minimises the possibility of any immediate tax consequences by debiting the amount of the overpayment first to the employer’s available subscribed capital (ASC) – the amount of a company’s share capital which can be distributed tax free to shareholders.

In the example, there is no reason to give the employer a deduction for $2,100, when the shares provided are worth only $1,400. If the employer were providing the shares itself, it would have a deduction of $1,400. So, the employer claims a deduction for $1,400 regardless of the reimbursement arrangement. The additional $700 payment is treated as return of capital by the employer to the parent. There is no black hole expenditure. All payments by the employer are recognised by the tax system, either as expenditure or distributions to shareholders.

Recommendation

That the submission be declined.

Issue: Deduction proposal is practically unworkable

Clause 41

Submission

(ANZ)

The proposal providing a deduction for the cost of providing employee share schemes by reference to an employee’s taxable income is practically unworkable. Employers will have difficulty determining an employee’s residence (if they earn the employee share scheme benefit partly in New Zealand and partly overseas, and thus apportion their income) and obtaining information in relation to former employees. Employees are likely to be reluctant to share this personal information and the information in their tax return with employers.

Comment

In relation to existing employees, employers are required to include income information in relation to each employee in their employer monthly schedule (EMS). All that is required is for an employer to aggregate these figures for the purpose of calculating its deduction. The proposed rules do not require the employer to confirm the amount each employee includes in their individual tax return.

It is not necessary that the figure used by the employer perfectly matches the figure used by the employee provided that each party uses the same vesting date and a market value that is permitted under CS 17/01 – valuation of employee share schemes. In most cases the discrepancy between the figures (if any) would be negligible.

In relation to former employees, the employer is not required to include income information on their EMS. However, officials understand that in most cases the relevant information can be requested from the share registry when the shares are issued or transferred to the employee.

In relation to employees who use the apportionment formula in proposed sections CE 2(5) and (6), use of this formula is not relevant to employers. It is only relevant to the employee. The employer’s expenditure in this case is calculated under proposed section DV 27(7) and (8). The calculation is not affected by proposed section CE 2(5) and (6). The apportionment that would be relevant to the employer is based on whether the expenditure has the necessary nexus with earning New Zealand taxable income (as is the standard test for any expenditure). If the nexus exists, it is irrelevant that the employee might not be New Zealand resident during part of the vesting period.

Officials have discussed the matter with the submitter, who has advised that they are able to deal with the issues raised in their submission within their current systems and no changes need to be made to the Bill to facilitate that.

Recommendation

That the submission be declined.

Issue: Clarification of deduction formula required

Clause 41

Submission

(ANZ)

The formula in proposed sections DV 27(7) and (8) – which calculates the employer’s deduction – requires clarification and should only apply to new grants. Specifically:

- The words “the shares, related rights, or employee share scheme” in the definition of “previous deductions” in proposed section DV 27(8)(b) should be amended to clarify that it is only the amount of any deductions in respect of costs attributable to the particular share scheme benefits which have given rise to taxable income to the employee in question which are to be taken into account. Under the drafting in the Bill, any costs attributable to the share scheme including in respect of benefits provided to other employees would be taken into account. That would likely then lead to a significant income amount under proposed section DV 27(9).

- The application of this rule should be clarified to ensure that it does not have retrospective application to prior year deductions where the rules at the time were clear that employers were entitled to a deduction. Consequently, the new rules should only apply to share benefits granted after enactment.

Comment

Officials agree with the first submission point. It is only deductions attributable to the benefits provided to the particular employee that should be reversed under proposed subsection (7).

Regarding the second submission point, officials do not believe any clarification is required. The Bill provides that the deduction rule will only apply from six months after enactment – see clause 2(25).

Recommendation

That the first submission point be accepted. That the second submission pointed be declined.

Issue: Bill should confirm that costs of setting up an employee share scheme are deductible

Clause 41

Submission

(Chapman Tripp)

The rules should be amended to confirm that the cost of setting up a scheme and accounting and legal fees (for setting up the scheme and on an on-going basis) fall within the meaning of “administrative or management services”.

Comment

The Bill is intended to give employers a deduction for the amount of the employee share scheme benefit taxable to an employee. It is not intended to deal with the deductibility of other employee share scheme costs. Whether or not the costs of setting up a scheme (including accounting and legal fees) are deductible should be determined under the general tests for whether an item is deductible. Accordingly, the Bill should be amended to ensure that the rule in proposed section DV 27 does not apply to deny deductions for the costs of setting up a scheme, and that these costs are subject to the usual capital/revenue tests.

This may mean that the costs of setting up an employee share scheme are blackhole expenditure. There is on-going policy work on blackhole expenditure generally, and this issue could be considered for inclusion on the Government’s tax policy work programme.

Recommendation

That the submission be declined and the Bill be amended to ensure that the rule in proposed section DV 27 does not apply to deny deductions for the costs of setting up a scheme.

Issue: Clarification as to timing of deduction

Clause 41

Submission

(Chapman Tripp)

The proposed rules should be amended to confirm that the timing of an employer’s deduction is the same as the employee’s share scheme taxing date.

This could be remedied by simply adding the following to section DV 27:

“Timing of employer’s deduction

(10) The person is allowed a deduction for the period in which the employee amount (referred to in subsection (8)(a)) arises.”

Comment

Officials believe proposed section DV 27(6) to (8) already establishes the time at which the employer is entitled to a deduction for providing an employee share scheme benefit. This is because, before the formula in proposed section DV 27(7) can apply, there must be an “employee amount” (that is, an amount of income the employee has derived from an employee share scheme under proposed section CE 2(1)). In the income year in which the employee has derived that amount, the employer is able to calculate – for that income year – its corresponding deduction. There is no need to state that the employer’s deduction arises in the same year in which the employee’s income arises, because this is the outcome already as a result of the mechanical operation of the proposed section.

Recommendation

That the submission be declined.

Issue: Deductions will be fiscally costly to the Government

Clause 41

Submission

(Olivershaw)

The proposals are likely to be fiscally costly to the Government since the Bill proposes allowing companies deductions for paper share option costs which currently are not tax deductible.

Comment

The cost of giving deductions to employers for employee share scheme benefits, including where those were not previously available, has been taken into account in forecasts for the entire package of measures that estimate an increase in revenue of $30 million per annum once fully phased in.

Officials note that since a deduction is now being allowed, and will undoubtedly be claimed, in situations where it previously was not, it will be important to ensure that income is also returned by employees.

Recommendation

That officials’ comment on the submission be noted.

Issue: Financial reporting adjustments will be required

Clause 41

Submission

(Spark)

There will be additional adjustments to the company’s tax return and associated financial reporting implications.

Comment

As is the case for many expenses, the deduction for employee share scheme benefits under tax law currently does not match the accounting expense figure, and this discrepancy has been manageable. It is likely that the proposals will create more consistency between financial reporting and tax rather than less. For example, officials are aware of many employee share schemes which currently give rise to an accounting expense under international financial reporting standards (IFRS) but no tax expense (for example, option schemes). Under the proposals in the Bill, there will now be a tax expense as well as an IFRS expense (albeit they are unlikely to match). Accordingly, officials do not believe this inconsistency should affect the proposals.

Recommendation

That officials’ comment on the submission be noted.

EXEMPT SCHEMES

Issue: Support retaining and modernising schemes

Clause 25

Submission

(BusinessNZ, Chapman Tripp, Chartered Accountants Australia and New Zealand, Corporate Taxpayers Group, Spark, KPMG, Roger Wallis, Russell McVeagh)

The submitters support retaining and modernising the widely-offered tax exempt schemes.

Recommendation

That the submitters’ support be noted.

Issue: Support for repeal of the notional 10% interest deduction

Clause 25

Submission

(Chartered Accountants Australia and New Zealand, Corporate Taxpayers Group, KPMG)

Submitters support the repeal of the notional 10% interest deduction.

Recommendation

That the submitters’ support be noted.

Issue: Support for the increased threshold for amount that can be spent purchasing shares

Clause 25

Submission

(Chartered Accountants Australia and New Zealand)

Support increasing the monetary threshold from $2,340 to $5,000.

Comment

Officials welcome this support. However, officials note that the current $2,340 threshold over three years is not being replaced by a $5,000 threshold, but rather a $3,000 per annum threshold. Under current law, the $2,340 monetary limit for an exempt scheme is not a limit on the amount of the benefit or the value of the shares. It is a limit on the amount that the employee pays for the shares, over a three year period. The limit is $2,340, or $780 per year. Under the Bill, there are two limits, one for the total value of the shares ($5,000 per annum) and one for the maximum discount offered to employees ($2,000 per annum). This means the maximum amount an employee can pay for the shares is $3,000 per annum (or $9,000 over three years), which is an increase of 385 percent on the current amount. It is this amount that is replacing the current threshold of $780 per annum (or $2,340 over three years).

Recommendation

That the officials’ comments be noted.

Issue: The threshold should be regularly reviewed in future

Clause 25

Submission

(Roger Wallis, Corporate Taxpayers Group)

The monetary thresholds that the Bill proposes to increase will need to be reviewed in future for inflation.

The legislation should provide for regular review (Roger Wallis).

Comment

Officials note that monetary thresholds in tax legislation are not generally indexed, and that in a low inflation environment, the administrative complexity of indexation may outweigh the benefit.

Recommendation

That the submission be declined.

Issue: The threshold should be higher

Clause 25

Submission

(EY)

To provide a meaningful compliance saving, the monetary thresholds need to be high enough to justify the creation and running of the schemes. The maximum value of shares provided under an exempt scheme should be $10,000 per year. The maximum discount an employer can provide to an employee should be $4,000 per year.

Comment

The exempt schemes are intended as a de minimis, to eliminate tax compliance costs for schemes providing modest benefits to 90 percent or more of a company’s employees. Given that the average wage in the March quarter of 2017 was approximately $62,000 per annum, a cap of $10,000 seems too high for a de minimis. Officials note that the 385 percent increase in the amount that can be spent by employees in an exempt scheme (to $3,000 per annum) is slightly below the level of wage inflation over the same period, which is 436 percent. A 436 percent increase would produce a figure of $3,400.

Recommendation

That the submission be declined.

Issue: There should be no limit on the minimum purchase price if an employee is required to buy shares

Clause 25

Submission

(Chartered Accountants Australia and New Zealand)

Some schemes do not require employees to pay anything for their shares. However, some schemes require employees to pay something for the shares, but they are generally given a discount to market value. If employees are required by the scheme to pay anything for the shares, the Bill currently requires that if there is a minimum amount employees are required to spend. This minimum should be no more than $1,000 per annum.

Chartered Accountants Australia and New Zealand submits that this $1,000 per annum limit is unnecessary. The monetary threshold is sufficient to ensure an exempt scheme is correctly targeted.

Comment

In cases where employers specify a minimum amount employees have to spend on shares to be eligible to participate in an exempt scheme, the purpose of capping that minimum amount is to make sure that employees on lower incomes are not effectively excluded from participation by the employers because the minimum amount they are required to spend is too high. So for example, if an employer required an employee to spend a minimum of $3,000 per annum buying shares, some employees would consider that too expensive (even with a loan from their employer) and the scheme would be targeted at higher earners by default.

Accordingly, officials disagree with the submission and consider that the $1,000 maximum is necessary.

Recommendation

That the submission be declined.

Issue: Share purchase schemes should be renamed “exempt schemes” in the legislation

Clause 25

Submission

(Roger Wallis)

The submitter proposes that the term “share purchase scheme” be instead replaced with the term “exempt employee scheme”. This is because:

- “share purchase agreement” is currently used in existing sections CE 2 – CE 7 of the Income Tax Act 2007 (although that phrase will be replaced by the more user-friendly “employee share scheme” by clause 12 of the Bill);

- as noted in the Commentary on the Bill, the concessionary regime is more commonly known as an “exempt scheme”;

- a concessionary scheme will not always involve a “purchase” element – under the Bill, employees can be conferred up to $2,000 of shares without having to make a purchase.

Comment

Officials agree that it would be helpful to rename the widely-offered share purchase shares “exempt employee share schemes”.

Recommendation

That the submission be accepted.

Issue: Loans to employee should not have a minimum repayment schedule

Clause 25

Submission

(Corporate Taxpayers Group)

Corporate Taxpayers Group submits that there should be greater flexibility with the loan arrangements with employees. The requirement in proposed section CW 26C(4)(d) states that the arrangement must provide that any loan to an employee to buy shares is repayable by regular instalments of a month or less. As currently drafted, this suggests it is compulsory for employers to require repayments of loans provided to employees to acquire shares to be made on at least a monthly basis.

Corporate Taxpayers Group submits that this requirement is overly restrictive. Currently the wording in section DC 13(4) states that the scheme must provide for employees to be able to repay the loan by regular equal instalments, which is an optional requirement. The Group submits that the treatment should be the same in the new rules which would, for example, allow an employer to set annual repayments.

Comment

The policy intention of both the existing provision and the proposed new provision is that repayment instalments should be regular enough so as to keep the repayment amounts affordable for employees. If the equal instalments were able to be, say, annual then it would be possible for these repayments to be quite large. This could allow employers to target only high income earners who can afford a large one-off repayment. To ensure the schemes are genuinely available to be taken up by all eligible employees, officials recommend retaining this requirement.

Recommendation

That the submission be declined.

Issue: Can payment by “regular instalment” include regular purchase of parcels of shares?

Clause 25

Submission

(Russell McVeagh)

It not clear whether “regular instalment” arrangements include arrangements where shares are acquired regularly by the employee (for example, each payday) with the entire purchase price paid off each time, or if it only applies to arrangements where shares are acquired and the purchase price is paid off in instalments.

Comment

The policy intention of this repayment by regular instalment requirement is to ensure the scheme is kept affordable for all employees. It is consistent with this policy aim to allow employees to purchase a smaller parcel of shares each payday. Accordingly, officials agree that either paying for or acquiring shares in regular instalments should be within the provision.

Recommendation

That the submission be accepted.

Issue: Support the reduction of eligible employees participating from all to 90 percent

Clause 25

Submission

(Chartered Accountants Australia and New Zealand)

Currently all employees must be offered the opportunity to participate in a widely-offered scheme for it to qualify as an exempt scheme. The submitter supports the reduction of the percentage of eligible employees from all to 90 percent.

Recommendation

That the submitter’s support be noted.

Issue: Support requirement to notify Commissioner of Inland Revenue (CIR) of scheme rather than request CIR approval

Clause 25

Submission

(Chartered Accountants Australia and New Zealand)

Currently the CIR must approve all widely-offered exempt schemes. The Bill proposes that employers self-assess their eligibility and simply notify the CIR that their scheme qualifies. The submitter supports the change from an approval, to a notification system.

Recommendation

That the submitter’s support be noted.

Issue: Support the removal of the trustee requirement

Clause 25

Submission

(Chartered Accountants Australia and New Zealand)

Currently all widely-offered exempt schemes must have a trustee to administer the scheme. This requirement is unnecessary and is being removed. The submitter supports this simplification.

Recommendation

That the submitter’s support be noted.

Issue: Support removing the deduction as the benefit is exempt

Clause 42

Submission

(KPMG)

KPMG supports removing the deduction as the benefit is exempt.

Recommendation

That the submitter’s support be noted.

Issue: Do not support removing the deduction for providing exempt benefits

Clause 42

Submission

(ANZ, BusinessNZ, Corporate Taxpayers Group, Russell McVeagh, Chartered Accountants Australia and New Zealand)