NRWT: Related party and branch lending

A special report from Policy and Strategy, Inland Revenue. April 2017.

NRWT: Related party and branch lending

The Taxation (Annual Rates for 2016–17, Closely Held Companies, and Remedial Matters) Act 2017 introduced a number of changes to the taxation of interest payments to non-residents.

This special report provides early information on the new NRWT and AIL rules, and precedes full coverage of the new legislation in the June edition of the Tax Information Bulletin.

Background

New Zealand imposes non-resident withholding tax (NRWT) on New Zealand-sourced interest paid to foreign lenders. The rate is 15%, usually reduced to 10% if the lender is resident in a country with which New Zealand has a double tax agreement. An obligation to withhold falls on the New Zealand borrower. NRWT is still a tax on the foreign investor and they will usually get a credit for the New Zealand tax against the tax they pay on the interest in their home jurisdiction.

A New Zealand borrower can elect to pay the 2% approved issuer levy (AIL) instead of withholding NRWT but only if they are borrowing from an unrelated lender – such as a foreign bank. Foreign lenders cannot claim a credit for AIL against home jurisdiction tax. This means it can be more tax-efficient for NRWT to be paid rather than AIL.

Broadly speaking, there are two parts to the reform package:

- changes to the NRWT rules generally to bring the rules dealing with timing and quantification of income subject to NRWT in line with the FA rules; and

- changes to the NRWT/AIL rules, which particularly affect branch structures.

The NRWT reform is about correcting anomalies in the rules to level the playing field for taxpayers to whom the NRWT rules apply (or are intended to apply). The changes focus on ensuring that an NRWT liability arises on interest on related party debt at approximately the same time that an income tax deduction is available to the borrower for that interest. Under the previous rules a number of structures delay or remove the liability for NRWT or replace it with AIL. Changes have also been introduced for related party lending by New Zealand banks.

The branch changes level the playing field between certain borrowers who can step around AIL and NRWT by operating an onshore or offshore branch, and other borrowers who cannot and are therefore subject to NRWT or AIL on interest paid to non-resident lenders. Much of the interest on funding that flows through a branch structure is ultimately paid to unrelated parties and will become subject to AIL although NRWT will continue to be available. One kind of structure involving related party lending and onshore branches is now subject to NRWT.

Proposals for these changes were consulted on in an officials’ issues paper, NRWT: Related party and branch lending, released in May 2015. Twenty-two submissions were received. Separate targeted consultation was subsequently held with the banking sector on the onshore branch notional interest proposals. Feedback from both consultations helped to shape the NRWT and AIL amendments in the new legislation, which was introduced in the Taxation (Annual Rates for 2016–17, Closely Held Companies, and Remedial Matters) Bill on 3 May 2016.

Further refinements to the proposals were recommended by the Finance and Expenditure Committee in response to submissions made at the select committee stage of the bill. The main recommendations included:

- a number of drafting changes to ensure the rules operate as intended and to assist interpretation;

- requiring the non-resident financial arrangement income (NRFAI) amount to be calculated under another spreading method if the borrower uses the fair value method or the market valuation method;

- removing amounts from NRFAI that have not and will not be received by the borrower;

- removing lending by a non-resident through their New Zealand branch from the scope of the NRFAI rules;

- adding an intention test to the back-to-back loan provision;

- clarifying and reducing the obligations of a direct lender that is party to a back-to-back loan;

- clarifying that the back-to-back loan provisions apply only when the debt is not already between related parties;

- removing interest amounts that are already subject to AIL from the notional loan rules;

- moving the date of the notional interest payment from the end of the income year to the end of the third month following the income year;

- extending the five-year grandparenting of the onshore branch changes to certain securitisation vehicles that raise funding from third parties to provide to other third parties; and

- removing the AIL registration proposals.

INTEREST ON RELATED PARTY LENDING

In broad terms, the amendments address “holes” in the NRWT base to ensure that the tax applies evenly to economically similar and easily substitutable transactions. They do not attempt to expand the NRWT base beyond its target of associated party interest, or interest which is logically indistinguishable from associated party interest.

Previously, differences in the timing of payments made under a loan from a non-resident parent company to its New Zealand subsidiary resulted in very different NRWT outcomes. For example, on an ordinary interest-paying loan, NRWT is payable every time interest is paid. However, for a zero-coupon bond, NRWT was not payable until the bond matured. This difference in the NRWT treatment was not mirrored in the income tax treatment for the borrower. The deduction for the borrower in an interest-bearing loan is similar to the deduction for the borrower in a zero-coupon bond. The deferral of the NRWT impost compared with the income tax benefit provided a significant timing benefit.

Another issue arose with the boundary between NRWT and AIL. While AIL is unavailable when the New Zealand borrower is controlled by the non-resident lender, it was available when a group of lenders were acting together and controlled the New Zealand borrower (typically a joint venture or private equity situations). This situation is difficult to distinguish economically from the case of a single non-resident controller – the group of shareholders are able to act as if they were a single controlling shareholder – yet the availability of AIL differed.

The effect of these (and certain other) issues was that non-resident investors who were able to take advantage of them faced a lower effective tax rate in New Zealand than other investors. This was not appropriate.

To address these issues the following changes have been introduced:

- NRWT must be paid at approximately the same time as interest is deducted by the New Zealand borrower, if the borrower and lender are associated. This means that the NRWT consequence of economically similar loan structures is similar; and

- the boundary between NRWT and AIL has been adjusted, so AIL is no longer available when a third party is interposed into what would otherwise be a related party loan or where a group of shareholders are acting together as one to control and fund the New Zealand borrower.

These changes bring the NRWT treatment of substantially similar transactions into line.

Application date

The amendments apply to existing arrangements on and after the first day of the borrower’s income year that starts after the date of enactment, being 30 March 2017.

For all other arrangements the amendments came into force on the date of enactment.

As the bill was enacted on 30 March 2017 the rules will apply to arrangements entered into after that date. For a taxpayer with a balance date between 30 March 2017 and 30 September 2017, the rules will apply to existing arrangements from the start of the 2017–18 year.

For taxpayers with a balance date between 1 October 2017 and 29 March 2018, the rules will apply to existing arrangements from the start of the 2018–19 year.

The changes to allow registered banks to pay AIL on associated party funding applied from the date of enactment.

Key features

Broadening arrangements giving rise to non-resident passive income

Non-resident passive income (NRPI) only arises when there is “money lent” (leaving aside dividends and royalties). Although the definition of “money lent” is broad, it did not apply in all situations when there was funding provided under a financial arrangement. This could result in a New Zealand borrower incurring financial arrangement expenditure when the non-resident lender had no NRPI.

The definition of “money lent” has been extended to include any amount provided to a New Zealand resident (or New Zealand branch of a non-resident) by an associated non-resident under a financial arrangement that provides funding to the resident, and under which the resident incurs financial arrangement expenditure. As “money lent” is a term used in other places in the Income Tax Act 2007, this change is limited to the NRWT rules.

Reducing quantum mismatches between NRPI and financial arrangement expenditure

To reduce mismatches between the NRWT and financial arrangement rules, the definition of “interest” has been extended to include a payment (whether of money or money’s worth) received by a non-resident from an associated New Zealand resident (or New Zealand branch of a non-resident), to the extent that the payment gives rise to expenditure to the borrower under the financial arrangement rules.

Related party debt

“Related party debt” is a new defined term. It covers all financial arrangements where a non-resident provides funds to an associated New Zealand resident (or New Zealand branch of an associated non-resident) and the borrower is allowed a deduction under the financial arrangement rules. To prevent this being structured around, it also includes funding provided through an indirect associated funding arrangement or by a member of a non-resident owning body – these terms are explained below.

A consequence of this definition is that money lent to exempt borrowers (such as charities) does not meet the “related party debt” definition. This is appropriate as no asymmetry can arise between income tax deductions and a lack of NRWT when there is no income tax deduction. Exempt borrowers continue to be required to withhold NRWT under payment rules that existed before the amendments, provided the other requirements are met.

Members of a banking group that are registered by the Reserve Bank are also carved out of having related party debt by section RF 12H(2). This is because amendments to section RF 12(1)(a)(ii) recognise that interest payments by New Zealand banks are directly or indirectly equivalent to third-party debt on which AIL can be paid. Although NRWT will continue to be available on interest payments by banks this can be eliminated by paying AIL instead and AIL does not apply on an accrual basis.

Arrangements that provide funds

For an arrangement to meet the definition of “related-party debt” one of the criteria it must satisfy, in section RF 12H(1)(a), is that the arrangement provides funds to another person. The purpose of this criterion is that NRWT on interest has historically applied to debt instruments and the amendments are intended to cover arrangements that are economically similar to debt. An arrangement that provides funds is intended to be narrower in scope than a financial arrangement.

The concept of a financial arrangement that “provides funds” already exists in a number of places in the Income Tax Act 2007.[1] Due to the wide variety of financial arrangements available it is not possible to provide an exhaustive list of particular arrangements that will or will not provide funding. However, the inclusion of this term in the NRWT rules is not intended to alter its interpretation as it previously applied.

When the thin capitalisation rules were introduced in 1995, commentary was provided on what the term “providing funds” meant. For reference these are included below:

Tax Information Bulletin Volume 7, Number 11, March 1996:

The term “provides funds” is not defined in the Act. It is intended to convey the broad concept that only arrangements that provide capital to the issuer should be included in the thin capitalisation regime.

Comment from officials in the Officials’ report on the Taxation (International Tax) Bill 1995:

However, it is recognised that certain financial instruments covered by the financial arrangement definition do not give rise to capital being made available to the New Zealand entity. These include certain hedging or speculative instruments, such as some foreign exchange transactions and certain swaps.

Tax Education Office Newsletter No 121, July 1996:

Linking the concept of debt to the “financial arrangement” definition potentially encompasses instruments and arrangements which may have no resemblance to standard interest bearing debt, eg futures contracts, swaps and options. However, section FG 4(2) [of the Income Tax Act 1994] specifies that the financial arrangement must provide funds to the issuer in order to be categorised as debt under the regime. This requirement is intended to ensure that only arrangements which provide capital to the borrower should be included as debt.

For example, swaps should be excluded from the definition of total debt, unless there is a real borrowing rather than simply a swap of interest or currency obligations. In the case of other financial derivatives, such as options and futures contracts, it is unlikely that such arrangements would fulfil the requirement of providing funds to the issuer.

Further to the examples provided above officials expect that a finance lease, which in substance is a loan, would generally provide funding whereas an operating lease would not. The examples above provide that a swap would not provide funds and this will generally be the case. One exception to this may be where the swap exchanges collateral which is available to the New Zealand resident; however, this would be very fact specific and would need to be considered on a case-by-case basis.

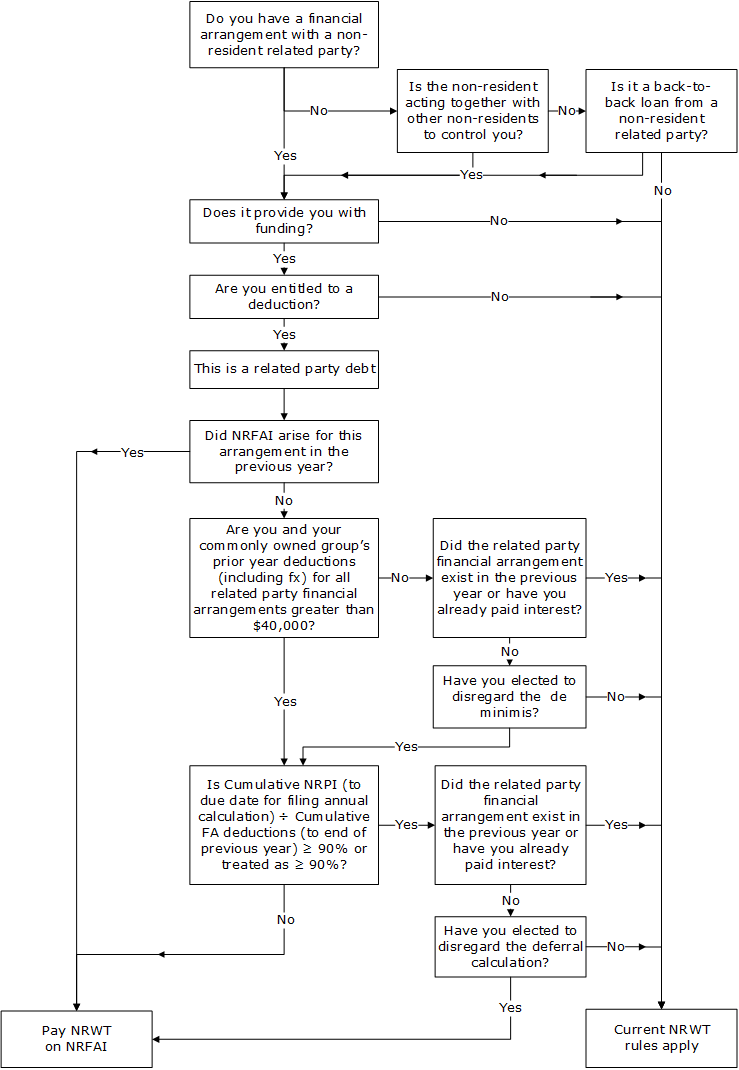

Calculating whether non-resident financial arrangement income arises

One of the principal concerns the amendments addressed is where interest payments (and therefore NRWT) significantly lagged accrued deductions. Although deductions can be accrued on a daily basis, interest is usually paid in arrears, frequently up to 12 months after the start of the interest period. These rules do not apply to arrangements when interest is accrued up to balance date but paid shortly thereafter; they are instead intended to cover more substantial deferrals.

To achieve this, taxpayers, for each related party debt are required to complete a deferral calculation, at the end of the second and subsequent years following issue of a financial arrangement, to determine whether non-resident financial arrangement income (NRFAI) arises.

Where the deferral calculation in section RF 2C(4) is satisfied, NRFAI does not arise and the related party debt continues to be taxed under the NRWT rules as they applied before the current amendments. The calculation that must be undertaken separately for each related party debt at the end of each income year is:

accumulated payments ÷ accumulated accruals ≥ 90%

These terms are defined in section RF 2C(5) as:

accumulated payments is the total interest paid since the financial arrangement became a related party debt until the due date for filing the NRWT return for the second month after the end of the income year.

accumulated accruals is the total expenditure the borrower incurs (excluding the effect of foreign exchange fluctuations) while the arrangement is a related party debt until the end of the year preceding the income year.

The period for the two variables is different, with “accumulated payments” covering payments made up to and somewhat beyond the end of the most recent completed income year while “accumulated accruals” excludes the most recently completed year. There are two reasons for this difference:

- This approach ensures NRFAI does not arise simply because interest is paid annually in arrears.

- “Accumulated payments” only requires knowing what interest has been paid whereas “accumulated accruals” requires a calculation under the financial arrangement rules, which might often not be made until shortly before the income tax return is filed. Using “accumulated accruals”, excluding the current year means the majority of the necessary calculations will have already been completed in the ordinary course of business (that is, whether or not these rules were introduced).

Applying a 90% threshold rather than a 100% threshold provides an additional buffer, so that the deferral calculation is not triggered when the majority of interest payments are paid on a 12-month or less deferral basis, but there is a limited amount of accrued interest – for example, when a bond is issued at a slight discount. This 90% discount also partially equalises the effect on arrangements that are entered into at different points prior to a balance date and before the first interest payment is made.

Once NRFAI arises in a year, section RF 2C (2)(a) requires NRWT to continue to apply on an accrual basis so long as the financial arrangement is related party debt. This means it will not be necessary for a taxpayer to repeat the above deferral calculation once the 90% threshold has been breached.

Record keeping requirements for NRFAI calculations

There is no prescribed form for the deferral calculation. Taxpayers will, however, be expected to complete and retain sufficient records to support their tax position. As the deferral calculation is only important in determining whether NRFAI has been derived, rather than the specific value of that calculation, the record keeping requirements should be broadly proportional to the significance of the calculation. For example, a related party debt that had regular interest payments equal to the interest accrued since the previous interest payment would not be expected to be near the 90% threshold so the records to support this would not need to be particularly detailed. Likewise a related party debt that did not have any interest payments would be treated as over 90% at the first NRFAI due date but would be less than 90% at the second NRFAI due date so again minimal records would be required. In contrast, a taxpayer that completed a deferral calculation showing that the result of the formula was 92% would need to maintain sufficient records to satisfy the Commissioner, if requested, that the 92% figure was accurate and should not instead be below 90%.

Related party de minimis threshold

If a New Zealand borrower has only a small amount of related party financial arrangement expenditure, the amount of the NRWT deferral, compared with income tax deductions, may not be sufficiently large to justify the additional compliance costs of having to apply the NRFAI rules.

Sections RF 2C(2)(b)(i) and RF 2C (3) carve out a borrower (and their related party lenders) from applying the NRFAI rules, except in relation to arrangements already subject to NRFAI, if their expenditure on related party debt in the previous year is less than $40,000. Unlike the rest of the NRFAI rules, to minimise compliance costs, this threshold includes foreign exchange movements on those financial arrangements so that a separate calculation is not required to be undertaken. The threshold also includes expenditure incurred by entities with a common ownership (66%) of the borrower, to prevent taxpayers avoiding the NRFAI rules by borrowing through multiple entities.

Timing of calculations and payment

The above deferral calculation should be completed as part of the preparation of the NRWT return for the second month after the borrower’s balance date. This NRWT return is due on the 20th of the third month after balance date. This date is defined in section RF 2C(7) as the “NRFAI due date”. Once NRFAI arises for a year, section RF 12E(1) deems it to be paid to the non-resident recipient on the final day of that second month. This determines the dates when the NRFAI must be included in a return and paid.

The exception to this timing is when a related party debt ceases during a year (the cessation date) in which case the income arising from the start of that year until the cessation date is treated by section RF 12E(2) as paid on the final day of the second month following the cessation date.

Foreign currency conversions

For arrangements denominated in foreign currency the income calculations are completed in that currency before any income subject to NRWT is converted into New Zealand dollars for the purpose of calculating the tax payable. The effect of this order is that foreign exchange movements are generally excluded[2] from NRFAI calculations.

The general rules for currency conversions in subpart YF apply for the NRWT rules. Section YF 1(2) converts foreign currency into New Zealand dollars by applying the close of trading spot exchange rate on the date at which the amount is required to be measured or calculated.

Section RF 12E provides that NRFAI is paid on the last day of the second month after a terminating event or the last day of the second month following the New Zealand borrower’s balance date. This is the date that section YF 1(2) requires the NRFAI amount to be converted into New Zealand dollars.

Voluntary election into NRFAI

The one-year deferral test above means that NRFAI cannot arise for an arrangement, including one with no regular interest payments, before the end of the second year of the arrangement. However, in some cases (for example, a zero coupon bond) it is self-evident that the instrument will give rise to NRFAI and a borrower may find it easier to apply NRFAI treatment from the inception of the arrangement. Section RF 12G allows taxpayers to elect to apply NRFAI from the first year the arrangement becomes a related party debt.

Taxpayers can also elect to disregard the application of the related party de minimis threshold. One reason they may choose to do this is when they expect to be above the de minimis threshold in future years.

First-year adjustment

The first year that a non-resident derives NRFAI on a related party debt, the borrower will need to calculate the non-resident’s income from the debt for that year using the financial arrangement rules. The method will be the same as the borrower applies to calculate their income tax deductions unless they apply the fair value or market valuation methods in which case another method must be chosen. The non-resident is also treated as deriving an additional amount of income, under section RF 12F, which removes the income deferral from that debt for all prior years, including any years the arrangement existed before enactment of the amendments.

Taxpayers who wish to avoid paying NRWT on pre-enactment deferral can prevent this by making sufficient interest payments after the enactment of the amendments so that NRFAI does not arise. This distinction arises as the deferral calculation covers only the period back to the day the arrangement became related party debt. Arrangements entered into before application of the new rules can only be related party debt from the first day of the first income year after that application date. Whereas the NRFAI calculation formula goes back to the date the person became party to the arrangement.

Amounts not received by the lender

The financial arrangement rules are intended to be sufficiently comprehensive that they include expenditure that will never be received by the lender – for example, when a borrower pays fees to a third party. As the NRFAI rules are designed to tax the lender on income they will receive, any amounts that will not be paid to them are excluded. This exclusion does not include amounts that are not received for other reasons, such as default by the borrower.

Figure 1: Do I need to pay NRWT on NRFAI?

(Full size | SVG source)

Examples

The following examples illustrate the main features of the new rules.

Example 1: Zero coupon bond

A Co has a 31 March balance date and issues a zero-coupon five-year bond with a face value of $1,000 to an associated non-resident on 1 August 2017. The bond is issued for $700. Deductions are calculated on a YTM basis with a 243/365ths apportionment between years.

| # | Date | Event | Payments | Deductions | Deduction > payment | Cash NRWT | NRFAI NRWT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 Aug 2017 | Arrangement commences | -700 | ||||

| 2 | 31 Mar 2018 | Balance date | 34.46 | ||||

| 3 | 20 Jun 2018 | NRFAI calculation date | N/A – First year | ||||

| 4 | 31 Mar 2019 | Balance date | 54.31 | ||||

| 5 | 20 Jun 2019 | NRFAI calculation date | 0 ÷ 34.46 = 0% = NRFAI triggered | (34.36 + 54.31) x 10% - 0 = 8.87 | |||

| 6 | 31 Mar 2020 | Balance date | 58.32 | ||||

| 7 | 20 Jun 2020 | NRFAI calculation date | Not required | 5.83 | |||

| 8 | 31 Mar 2021 | Balance date | 62.63 | ||||

| 9 | 20 Jun 2021 | NRFAI calculation date | Not required | 6.26 | |||

| 10 | 31 Mar 2022 | Balance date | 67.27 | ||||

| 11 | 20 Jun 2022 | NRFAI calculation date | Not required | 6.72 | |||

| 12 | 30 Sep 2022 | Maturity | 1,000 | 0 | |||

| 13 | 20 Dec 2022 | Maturity NRFAI calculation | 2.30 | ||||

| 14 | 31 Mar 2023 | Balance date | 23.01 | ||||

| Total | 300 | 300 | 30 | ||||

The balance date entries in #2, 4, 6, 8, 10 and 14 represent income tax deductions available for the return period ending on that date. These may not be calculated until after this date, though the requirement to calculate and pay provisional tax may mean that the company does in fact calculate them earlier than the balance date. The same also applies for the later examples.

The maturity NRFAI calculation in #13 is due on the due date for the NRWT return for the period two months after maturity even though the income tax deduction may not be calculated until sometime after balance date.

As this arrangement has no regular interest payments, A Co would be aware from the outset that NRFAI would eventually arise. Therefore, it may elect to apply NRFAI from the commencement date which would result in an NRWT payment of $3.45 at #3 and the NRWT payment at #5 reducing to $5.43. Although this would be cashflow negative it may reduce compliance costs.

Example 2: Interest paid less than interest accruing

B Co has a 31 March balance date and borrows NZ$1,000 from an associated non-resident on 2 April 2017. B Co will pay $60 of interest on 1 April each year and $1,300 upon maturity on 1 April 2022. Deductions are calculated on a YTM basis with a 364/365ths apportionment between years.

| # | Date | Event | Payments | Deductions | Deduction > payment | Cash NRWT | NRFAI NRWT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 Apr 2017 | Arrangement commences | -1,000 | ||||

| 2 | 31 Mar 2018 | Balance date | 108.03 | ||||

| 3 | 1 Apr 2018 | Coupon date | 60 | 6 | |||

| 4 | 20 Jun 2018 | NRFAI calculation date | N/A – First year | ||||

| 5 | 31 Mar 2019 | Balance date | 113.55 | ||||

| 6 | 1 Apr 2019 | Coupon date | 60 | 6 | |||

| 7 | 20 Jun 2019 | NRFAI calculation date | 120 ÷ 108.03 = 111.1% | ||||

| 8 | 31 Mar 2020 | Balance date | 119.35 | ||||

| 9 | 1 Apr 2020 | Coupon date | 60 | 6 | |||

| 10 | 20 Jun 2020 | NRFAI calculation date | 180 ÷ 221.58 = 81.2% = NRFAI triggered | (108.03 + 113.55 + 119.35) x 10% - 18 = 16.09 | |||

| 11 | 31 Mar 2020 | Balance date | 125.78 | ||||

| 12 | 1 Apr 2021 | Coupon date | 60 | Not required | |||

| 13 | 20 Jun 2021 | NRFAI calculation date | Not required | 12.58 | |||

| 14 | 31 Mar 2022 | 31 Mar 2022 | 132.91 | ||||

| 15 | 1 Apr 2022 | Maturity | 1,360 | Not required | |||

| 16 | 20 Jun 2022 | NRFAI calculation date | Not required | 13.29 | |||

| 17 | 20 Jul 2022 | Maturity NRFAI calculation | 0.04 | ||||

| 18 | 31 Mar 2023 | Balance date | 0.36 | ||||

| Total | 600 | 600 | 60 | ||||

Although the interest payment at #9 is paid after the end of the March 2020 tax year, which is the first one NRFAI arises in, it is not expected the NRFAI 90% calculation will have been completed by this date as it is not yet due. This is the reason NRWT on a payments basis is still required; however credit is given for this in the 90% calculation.

Example 3: Interest accruing but not credited to account

C Co has a 30 June balance date and a loan facility from an associated non-resident with an interest rate of 10% pa on the outstanding balance, payable at the demand of the lender. C Co draws down $1,000 from this facility on 1 July 2017. The lender demands annual interest payments of $100 for the first four years. The lender then stops demanding interest payments and the borrower does not credit them to the lender’s account, although interest continues to accrue on an annually compounding basis. C Co calculates its expenditure from the facility under the IFRS financial reporting method.

| # | Date | Event | Payments | Accrued interest | Deductions | Deduction > payment | Cash NRWT | NRFAI NRWT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 Jul 2017 | Facility draw-down | -1,000 | |||||

| 2 | 30 Jun 2018 | Balance date | 100 | 100 | 10 | |||

| 3 | 20 Sep 2018 | NRFAI calculation date | N/A – First year | |||||

| 4 | 30 Jun 2019 | Balance date | 100 | 100 | 10 | |||

| 5 | 20 Sep 2019 | NRFAI calculation date | 200 ÷ 100 = 200% | |||||

| 6 | 30 Jun 2020 | Balance date | 100 | 100 | 10 | |||

| 7 | 20 Sep 2020 | NRFAI calculation date | 300 ÷ 200 = 150% | |||||

| 8 | 30 Jun 2021 | Balance date | 100 | 100 | 10 | |||

| 9 | 20 Sep 2021 | NRFAI calculation date | 400 ÷ 300 = 133.3% | |||||

| 10 | 30 Jun 2022 | Balance date | 100 | 100 | 0 | |||

| 11 | 20 Sep 2022 | NRFAI calculation date | 400 ÷ 400 = 100% | |||||

| 12 | 30 Jun 2023 | Balance date | 110 | 110 | 0 | |||

| 13 | 20 Sep 2023 | NRFAI calculation date | 400 ÷ 510 = 78.4% = NRFAI triggered | 610 x 10% - 40 = 21 | ||||

| 14 | 30 Jun 2024 | Balance date | 121 | 121 | Not required | |||

| 15 | 20 Sep 2024 | NRFAI calculation date | Not required | 12.10 | ||||

| Total | 400 (excluding principal) | 331 | 731 | 73.10 | ||||

Even if C Co started paying interest again, this arrangement would stay in NRFAI. If it wanted to eliminate NRFAI it would need to repay the loan and replace it with a new one.

Example 4: Arrangements entered into before application date

D Co has three separate loans from its non-resident parent. All three loans were for $2,000 and were drawn down on 1 April 2015 with no periodic interest payments and a single repayment amount of $2,500 on 31 March 2020. Due to its 31 March balance date, the NRFAI rules apply to D Co from 1 April 2017. On 1 April 2017 Loan 1 continues as originally intended, Loan 2 is repaid at the amount accrued on that date and replaced by a new loan that has annual interest payments and is repaid on 31 March 2020 and Loan 3 is restructured to have annual interest payments on 31 March each year for interest accrued after 1 April 2017 with the balance repaid upon maturity.

Loan 1:

| # | Date | Event | Payments | Deductions | Deduction > payment | Cash NRWT | NRFAI NRWT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 Apr 2015 | Arrangement commences | -2,000 | ||||

| 2 | 31 Mar 2016 | Balance date | 0 | 91.28 | 0 | ||

| 3 | 31 Mar 2017 | Balance date | 0 | 95.45 | 0 | ||

| 4 | 1 Apr 2017 | NRFAI rules apply | |||||

| 5 | 31 Mar 2018 | Balance date | 0 | 99.80 | 0 | ||

| 6 | 20 Jun 2018 | NRFAI calculation date | N/A – First year | ||||

| 7 | 31 Mar 2019 | Balance date | 0 | 104.36 | |||

| 8 | 20 Jun 2019 | NRFAI calculation date | 0 ÷ 99.80 = 0% = NRFAI triggered | (91.28 + 95.45 + 99.80 + 104.36) x 10% = 39.09 | |||

| 9 | 31 Mar 2020 | Maturity | 2,500 | 109.12 | Not required | ||

| 10 | 20 Jun 2020 | Maturity NRFAI calculation date | Not required | 10.91 | |||

| Total | 500 | 500 | 50.00 | ||||

Loan 2 & new loan:

| # | Date | Event | Payments | Deductions | Deduction > payment | Cash NRWT | NRFAI NRWT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 Apr 2015 | Arrangement commences | -2,000 | ||||

| 2 | 31 Mar 2016 | Balance date | 0 | 91.28 | 0 | ||

| 3 | 31 Mar 2017 | Balance date | 0 | 95.45 | 0 | ||

| 4a | 1 Apr 2017 | NRFAI rules apply – loan 2 repaid | 2,186.72 | 18.67 | |||

| 4b | 1 Apr 2017 | NRFAI rules apply – new loan drawn | -2,186.72 | ||||

| 5 | 31 Mar 2018 | Balance date | 99.80 | 99.80 | 9.98 | ||

| 6 | 20 Jun 2018 | NRFAI calculation date | N/A – First year | ||||

| 7 | 31 Mar 2019 | Balance date | 99.80 | 99.80 | 9.98 | ||

| 8 | 20 Jun 2019 | NRFAI calculation date | (99.80 + 99.80) ÷ 99.80 = 200% | ||||

| 9 | 31 Mar 2020 | Maturity new loan | 2,286.52 | 99.80 | 9.98 | ||

| 10 | 20 Jun 2020 | Maturity NRFAI calculation date | |||||

| Total | 486.13 | 486.13 | 48.61 | ||||

Loan 3:

| # | Date | Event | Payments | Deductions | Deduction > payment | Cash NRWT | NRFAI NRWT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 Apr 2015 | Arrangement commences | -2,000 | ||||

| 2 | 31 Mar 2016 | Balance date | 0 | 91.28 | 0 | ||

| 3 | 31 Mar 2017 | Balance date | 0 | 95.45 | 0 | ||

| 4 | 1 Apr 2017 | NRFAI rules apply | |||||

| 5 | 31 Mar 2018 | Balance date | 99.80 | 99.80 | 9.98 | ||

| 6 | 20 Jun 2018 | NRFAI calculation date | N/A – First year | ||||

| 7 | 31 Mar 2019 | Balance date | 99.80 | 99.80 | 9.98 | ||

| 8 | 20 Jun 2019 | NRFAI calculation date | (99.80 + 99.80) ÷ 99.80 = 200% | ||||

| 9 | 31 Mar 2020 | Maturity | 2,286.52 | 99.80 | 28.65 | ||

| 10 | 20 Jun 2020 | Maturity NRFAI calculation date | |||||

| Total | 486.13 | 486.13 | 48.61 | ||||

Example 5: Foreign currency borrowing:

E Co has a 31 March balance date and borrows US$1,000 from an associated non-resident on 2 April 2017. E Co will pay US$60 of interest on 1 April each year and US$1,300 upon maturity on 1 April 2022. Deductions are calculated on a YTM basis with a 364/365ths apportionment between years.

Assume the exchange rates shown in the table below:

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calculating whether NRFAI arises | Calculating US$ tax liability | Converting tax liability to NZ$ | |||||||||

| # | Date | Event | Payments (US$) | Deductions (US$) | Deduction > payment | Cash NRWT (US$) | NRFAI NRWT (US$) | Exchange rate | Payments (NZ$) | Cash NRWT (NZ$) | NRFAI NRWT (NZ$) |

| 1 | 2 Apr 17 | Arrangement commences | -1,000 | 0.80 | -1,250 | ||||||

| 2 | 31 Mar 18 | Balance date | 108.03 | 0.79 | |||||||

| 3 | 1 Apr 18 | Coupon date | 60 | 6 | 0.79 | 75.95 | 7.60 | ||||

| 4 | 20 Jun 18 | NRFAI calculation date | N/A – First year | 0.76 | |||||||

| 5 | 31 Mar 19 | Balance date | 113.55 | 0.56 | |||||||

| 6 | 1 Apr 19 | Coupon date | 60 | 6 | 0.56 | 107.14 | 10.71 | ||||

| 7 | 20 Jun 19 | NRFAI calculation date | 120 ÷ 108.03 = 111.1% | 0.64 | |||||||

| 8 | 31 Mar 20 | Balance date | 119.35 | 0.71 | |||||||

| 9 | 1 Apr 20 | Coupon date | 60 | 6 | 0.71 | 84.51 | 8.45 | ||||

| 10 | 20 Jun 20 | NRFAI calculation date | 180 ÷ 221.58 = 81.2% = NRFAI triggered | (108.03 + 113.55 + 119.35) x 10% - 18 =16.09 | 0.71 | 22.66 | |||||

| 11 | 31 Mar 21 | Balance date | 125.78 | 0.76 | |||||||

| 12 | 1 Apr 21 | Coupon date | 60 | Not required | 0.76 | 78.95 | |||||

| 13 | 20 Jun 21 | NRFAI calculation date | Not required | 12.58 | 0.81 | 15.53 | |||||

| 14 | 31 Mar 22 | Balance date | 132.91 | 0.82 | |||||||

| 15 | 1 Apr 22 | Maturity | 1,360 | Not required | 0.82 | 1,658.54 | |||||

| 16 | 20 Jun 22 | NRFAI calculation date | Not required | 13.29 | 0.80 | 16.61 | |||||

| 17 | 20 Jul 22 | Maturity NRFAI calculation | 0.04 | 0.80 | 0.05 | ||||||

| 18 | 31 Mar 23 | Balance date | 0.36 | 0.84 | |||||||

| Total | 600 | 600 | 60 | 755.09 | 81.61 | ||||||

Notes:

- These US$ calculations are identical to the NZ$ borrowing in example 2 except the NRWT amount needs to be converted to NZ$ as shown in the four rightmost columns.

- The income tax deduction shown in column 5 is calculated in US$ before being converted into NZ$. This conversion is not shown in the table above.

- Following these rules NRWT of NZ$81.61 is paid. This compares to NRWT under the existing payment basis NRWT rules of NZ$78.54. Whether the NRFAI rules result in higher or lower NZ$ NRWT will depend on how exchange rates move over the term of the arrangement.

Officials agreed in the Officials’ report to the bill that introduced these rules to provide novation examples which are set out below.Some of the facts in these examples appear non-commercial but are provided to illustrate how the NRFAI rules would apply.

Example 6: Novation – borrower pays less than face value

NZ Co borrows $1,000 from its non-resident parent US Co with annual interest payments of $50 and the principal repaid upon maturity in 10 years.

For each of the first three years NZ Co pays $50 interest and withholds $5 of NRWT. As NZ Co’s interest deductions and payments match, the deferral calculation is not triggered so NRFAI does not arise.

At the start of year four NZ Co pays NZ Sub Co, a related party, $800 to take over its obligation under the loan. NZ Co is no longer party to the financial arrangement so completes a base price adjustment that shows $200 of income. NZ Sub Co spreads the $200 difference between the amount it received and the principal repayment over the remaining six years of the arrangement.

At the end of year four NZ Sub Co pays $50 interest and withholds NRWT. The deferral calculation at the end of year four is treated as more than 90% under section RF 2C(6). The deferral calculation at the end of year five does not include any portion of the $200 deduction as this amount is expenditure that is not, and will not be, received by US Co so is excluded under section RF 12D(3).

Example 7: Novation – borrower pays more than face value

NZ Co borrows $1,000 from its non-resident parent US Co with annual interest payments of $50 and the principal repaid upon maturity in 10 years.

For each of the first three years NZ Co pays $50 interest and withholds $5 of NRWT. As NZ Co’s interest deductions and payments match the deferral calculation is not triggered so NRFAI does not arise.

At the start of year four NZ Co pays NZ Sub Co, a related party, $1,200 to take over its obligation under the loan. NZ Co is no longer party to the financial arrangement so completes a base price adjustment that shows a $200 deduction. NZ Sub Co spreads the $200 difference between the amount they received and the principal repayment over the remaining six years of the arrangement.

At the end of year four NZ Sub Co pays $50 interest and withholds NRWT. The deferral calculation at the end of year four is treated as more than 90% under section RF 2C(6). The deferral calculation at the end of year five and each subsequent year shows cumulative payments exceed cumulative deductions so NRFAI is never triggered and NRWT remains on a payments basis.

Example 8: Assignment

NZ Co borrows $1,000 from its non-resident parent US Co with no annual interest payments and $2,000 repaid upon maturity in 10 years. The YTM spread is:

| Year | Cashflow | Deduction | Accrued balance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1,000 | 1,000.00 | |

| 1 | 0 | 71.77 | 1,071.77 |

| 2 | 0 | 76.92 | 1,148.70 |

| 3 | 0 | 82.45 | 1,231.14 |

| 4 | 0 | 88.36 | 1,319.51 |

| 5 | 0 | 94.71 | 1,414.21 |

| 6 | 0 | 101.50 | 1,515.72 |

| 7 | 0 | 108.79 | 1,624.50 |

| 8 | 0 | 116.60 | 1,741.10 |

| 9 | 0 | 124.96 | 1,866.07 |

| 10 | -2,000 | 133.93 | 0.00 |

The deferral calculation at the end of year 1 is treated as more than 90% but at the end of year two is 0% so NRFAI is triggered. NRFAI at year two, including the first year adjustment, is $148.69 so NRWT of $14.87 is paid.

At the start of year three US Sub Co, a related party, pays US Co $1,100 to take over its rights in the loan. At the end of year three NZ Co is still party to the same arrangement and it is still a related party debt so they pay NRWT of $8.25 on the deemed income of $82.45 for the year.

At the end of the arrangement US Co will have derived $100 profit with $15.39 of NRWT withheld while US Sub Co will have derived $900 profit with $84.61 of NRWT withheld. This difference arises as the amount paid by US Sub Co for the assignment is less than the accrued value at the time of the assignment.

Defining when payments are to a related person

New Zealand borrowers that meet the requirements of section RF 12(1)(a) can pay AIL on a payment of interest that is NRPI. When AIL is paid, this NRPI qualifies for a zero-rate of NRWT. The requirements of section RF 12(1)(a) include that the borrower is not associated with the lender, unless the borrower is a member of a New Zealand banking group.

Back-to-back loans and multi-party arrangements

Before the enactment of the new rules the NRWT and AIL rules did not “look through” to the ultimate lender to a New Zealand borrower. Leaving aside the possible application of the general anti-avoidance provision, this allowed a New Zealand borrower to interpose one or more third parties into what would otherwise be a loan from an associated person. An example of this type of arrangement is a back-to-back loan.

Arrangements have also been entered into that are not back-to-back loans in the conventional sense but which also involve indirect funding by a non-resident lender to a resident associated borrower without the imposition of NRWT, while maintaining an income tax deduction calculated under the financial arrangement rules.

Amendments now define these back-to-back loans and multi-party arrangements as “indirect associated funding” if they are entered into with the purpose or effect that the borrower incurs financial arrangement expenditure and the associate does not derive non-resident passive income from the borrower. Interest payments on indirect associated funding are ineligible for AIL and the New Zealand-resident (or New Zealand branch of a non-resident) borrower will have to consider whether NRFAI arises if interest payments on indirect associated funding have an inappropriate amount of deferral compared with income tax deductions.

Indirect associated funding arises when a non-resident associate of a New Zealand borrower provides funding, directly or indirectly, to a third party so it can be provided to the New Zealand borrower or to reimburse the third party for funds provided to the New Zealand borrower. This also applies to arrangements where part of the funding is provided by an associated non-resident and part is provided by the third party. This is achieved by treating any amount lent by or repaid to the associate as being lent directly to the New Zealand borrower rather than the third party. Any interest payments made by the New Zealand borrower to the third party are treated as being made by the New Zealand borrower to the third party as agent for the associate, to the extent they are attributable to money lent by the associate.

The amendments capture all arrangements involving a New Zealand borrower, third party and an associated non-resident if there is some linkage between the two amounts of funding provided, but not arrangements where there is no linkage, other than the existence of a common third party.

If a borrower does not withhold NRWT on an indirect funding arrangement the direct lender will be required to do so (even if they are themselves a New Zealand resident). This is consistent with the existing treatment of NRWT not being withheld by a payer, aside from the following points:

- The direct lender will not have an obligation to deduct NRWT from the payment received if they have taken actions to confirm this is not a back-to-back loan but have incorrect information. For example if the borrower incorrectly represents that this is not a back-to-back loan.

- If the arrangement has insufficient interest payments that result in the NRFAI deferral calculation for the borrower being less than 90%, the borrower is required to pay NRWT on the NRFAI. The direct lender cannot be expected to know that this arrangement is NRFAI or the amount of NRFAI calculated so will continue to have the same obligations as above on any interest payments received. Any NRWT withheld by the direct lender on a payments basis will be available to the borrower and/or indirect lender to meet any NRWT liability arising on an NRFAI basis.

- In the event that the above NRWT was not withheld/paid by the relevant parties Inland Revenue would commence collection activity consistent with other debts. Inland Revenue would generally seek to collect this tax from the borrower or the indirect lender in the first instance before seeking to collect from the direct lender and would not seek to recover this tax from the direct lender when they did not originally have an obligation to withhold under the principles above.

Example 9: Commercial arrangement

Foreign Parent has $1,000,000 on deposit with Australian Bank while its subsidiary, NZ Sub, has a $500,000 loan from Australian Bank NZ Branch. Both the deposit and loan are on independent arm’s length terms. Withdrawal of the deposit will have no effect on the loan, and the deposit is not security for the loan’s repayment. In this case, Foreign Parent is not considered to have provided this deposit so that Australian Bank could lend it to NZ Sub. Therefore, this is not indirect associated funding.

Example 10: Back-to-back loan

NZ Co has a $1,000,000 loan from NZ Bank on which it pays 5% interest. NZ Co’s parent, Aus Hold Co has a $700,000 deposit with Aus Bank, the Australian parent of NZ Bank on which it receives 4.9% interest. Bank lending documents show NZ Co pays 5%, instead of 6% charged to other borrowers, due to Aus Hold Co’s deposit, and withdrawal of the deposit triggers a right for the Bank to demand repayment of, or to increase the interest rate on, the loan. The new provisions impose NRWT as follows. This analysis would also apply if NZ Bank were instead a branch of Aus Bank.

This arrangement is treated as an indirect funding arrangement with a $700,000 loan from Aus Hold Co (the indirect lender) to NZ Co (the borrower) and a $300,000 loan from NZ Bank (the direct lender) to NZ Co. NZ Co makes $50,000 annual interest payments (the first interest payment) to NZ Bank and Aus Bank makes $34,300 annual interest payments (the second interest payment) to Aus Hold Co. The first interest payment is treated as a $34,300 interest payment from NZ Co to NZ Bank as agent for Aus Hold Co on which the borrower must withhold NRWT and a $15,700 interest payment from NZ Co to NZ Bank which is treated in the standard manner (NZ Bank has an RWT exemption certificate so no RWT is withheld; however, this is assessable income to NZ Bank). The second interest payment from Aus Bank to Aus Hold Co is treated as a payment of money held as an agent so no NRWT or AIL is required.

If NZ Co did not withhold NRWT NZ Bank would be required to pay NRWT on $34,300 of the $50,000 interest payment it received from NZ Co.

Example 11: NRFAI and obligations on the direct lender

NZ Co has a 31 March balance date and borrows NZ$1,000 from a third party finance company (NZ Finance Co) on 2 April 2017. This example uses the same figures from example 2. NZ Co will pay $60 of interest on 1 April each year and $1,300 upon maturity on 1 April 2022. Deductions are calculated on a YTM basis with a 364/365ths apportionment between years. On 2 April 2017 NZ Finance Co also borrows $1,000 from NZ Co’s non-resident parent with interest of $55 on 1 April each year and $1,300 upon maturity on 1 April 2022. NZ Finance Co is a NZ resident with an RWT exemption certificate.

Assuming these two loans are back-to-back loans, this will be an indirect associated funding arrangement so NZ Co is required to withhold $5.50 of NRWT (assuming 10% is the appropriate withholding tax rate for a payment by NZ Co to its parent) on each $60 interest payment to NZ Finance Co. The NRWT is $5.50 as only $55 of the $60 interest payment is treated as received on behalf of NZ Co’s non-resident parent. The terms of the loan between NZ Co and NZ Finance Co require NZ Co to gross the interest payments up so that NZ Finance Co continues to receive $60. On 20 June 2020 NZ Co advises NZ Finance Co that this arrangement has triggered the NRFAI rules and that NRWT will no longer be withheld on the remaining interest payments. NZ Co will be required to pay NRWT to Inland Revenue on the NRFAI arising and neither NZ Co or NZ Finance Co will pay NRWT on the interest payments to NZ Finance Co.

Example 12: NRFAI and obligations on the direct lender

This example is the same as example 11 above, except NZ Co does not comply with its tax obligations.

Upon receiving the $60 interest payment with no NRWT withheld, NZ Finance Co will be required to pay $5.50 of NRWT to Inland Revenue. It is expected the loan agreement would allow NZ Finance Co to recover this amount from NZ Co. On 21 June 2020 NZ Co advises NZ Finance Co that the arrangement has triggered NRFAI so NZ Finance Co stops paying NRWT on interest payments after that date. NZ Co would continue to have a liability for NRWT on the interest payments and NRFAI once the deferral calculation was triggered on 20 June 2020 however, the total amount payable would be reduced by any NRWT paid by NZ Finance Co.

To the extent insufficient NRWT was paid, Inland Revenue would commence collection actions. The attempts to collect this NRWT would likely be from NZ Co and NZ Co’s non-resident parent in the first instance. Inland Revenue could also attempt to collect NRWT from NZ Finance Co if this was unsuccessful; however, the maximum amount that could be collected from NZ Finance Co would be capped at NRWT on a payments basis for interest payments before they received the NRFAI notification (that is, $5.50 in each of the April 2018 to April 2020 periods).

Example 13: Commercial cash pooling arrangement

Multinational Group has subsidiaries in a number of countries including New Zealand. Each of these subsidiaries has a notional cash pooling account with Worldwide Bank Ltd which it uses for managing its working capital requirements. The New Zealand subsidiary’s balance in the cash pooling account can be positive or negative within limits agreed with Worldwide Bank. During the month of June 2018 the New Zealand subsidiary’s average balance is -$50,000 while the parent company’s average balance is +$750,000. Worldwide Bank does not charge the New Zealand subsidiary interest for June 2018. The parent company has not put money into the cash pool in order for money to be withdrawn by the New Zealand subsidiary so this is not indirect associated funding and the new rules do not apply. This conclusion is not affected if there is a compensatory payment by the New Zealand subsidiary to the parent.

Example 14: Back-to-back loan through a cash pooling arrangement

US Parent has a $10,000,000 loan to NZ Subsidiary on which the interest payments are subject to NRWT. NZ Subsidiary repays this loan by withdrawing from an account with US Bank. This account is part of a cash pooling arrangement with other members of US Parent’s group. US Parent uses the $10,000,000 repaid by NZ Subsidiary to make a deposit with US Bank in an account that is also part of the cash pooling arrangement. Because these amounts offset each other, US Parent does not receive any interest from US Bank but neither does NZ Subsidiary pay interest to US Bank. NZ Subsidiary pays $100,000 per month to US Parent as part of a transfer pricing agreement which is a deductible funding cost to NZ Subsidiary. Section RF 12J treats this arrangement as a loan from US Parent to NZ Subsidiary. This means that the $100,000 per month payment is New Zealand-sourced income for US Parent, from which NRWT must be withheld.

Example 15: Sale of part of a loan to borrower’s associate

NZ Co borrows $1,000 from NZ Bank with $100 annual interest payments and the $1,000 repaid in five years. As part of the same arrangement, NZ Bank sells the principal repayment to Aus Parent Co, the ultimate owner of NZ Co for $600. For tax purposes this is treated as two separate financial arrangements, a five-year $400 amortising loan from NZ Bank to NZ Co and a five-year $600 bullet loan from Aus Parent Co to NZ Co as follows:

| From | To | Arrangement commences | Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 | Year 4 | Year 5 | Total interest |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NZ Bank | NZ Co | -400 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Aus Parent Co | NZ Co | -600 | 1,000 | 400 |

There is no equivalent amount paid by NZ Bank to Aus Parent Co so the $100 interest payments by NZ Co to NZ Bank are treated as payments of principal and interest between two New Zealand residents under the financial arrangements rules. The $1,000 final payment, whether paid directly to Aus Parent Co or paid to NZ Bank as agent for Aus Parent Co is treated as a $600 principal repayment and a $400 interest payment from NZ Co to Aus Parent Co, therefore NZ Co must withhold NRWT. However, as NZ Co is claiming financial arrangement deductions for funding provided by an associated non-resident, this arrangement will trigger NRFAI on which NRWT will be required to be paid by NZ Co over the term of the arrangement.

Acting together

Before the amendments were made, the non-association tests for accessing the AIL rules relied on the associated persons definition in subpart YB. One of the tests in the associated person rules states that two companies are associated if a group of persons exists whose total voting interests in each company are 50 percent or more.

This means that if two or more companies each had ownership interests of less than 50 percent in a New Zealand borrower, these companies were not associated with that borrower unless they are themselves associated.

Transactions were identified where two or more non-associated persons (investors), each with less than 50 percent ownership interests in a New Zealand borrower, together provided debt funding to that borrower under an arrangement. Even though these investors may have been genuinely not associated (for example, three pension funds for quite different groups of employees) they could make decisions about the borrower collectively, and in economic substance, operate in a similar manner as if they were a single owner.

By operating in this manner, the investors could make decisions in a similar manner to a single owner such as inserting debt (subject to thin capitalisation requirements) in proportion to their ownership interests and thereby received a return on their total (equity + debt) investment with a large proportion of this being deductible in New Zealand.

This problem was not unique to the NRWT/AIL rules. Until recently, the same structure meant the thin capitalisation rules did not restrict the New Zealand borrower’s interest deductions. In March 2017 the Government also announced proposals to address this issue in relation to transfer pricing.

To prevent this, “related party debt” now includes funding provided by a member of a non-resident owning body. This means:

- interest payments on this funding are ineligible for AIL; and

- when interest payments are inappropriately deferred compared with deductions, the arrangement may generate NRFAI.

A non-resident owning body was an existing concept within the thin capitalisation rules; this definition has now been moved to section YA 1. The thin capitalisation “acting together” rules were explained in greater detail in Tax Information Bulletin Volume 26, No 7, August 2014. In short, a non-resident owning body is a group of non-residents or entities (such as trusts settled by non-residents), that have one or more characteristics indicating they are acting together to debt-fund a New Zealand company. These characteristics include:

- having proportionate levels of debt and equity among the group;

- an agreement that sets out how the company should be funded with member-linked funding if the company is not widely held (a term defined in section YA 1); and

- member-linked debt in the company in a way recommended by a person (such as a private equity manager), or implemented by a person on behalf of the members.

Proportionality is a characteristic of acting together as it generally requires a degree of coordination to achieve. More generally, proportionality is also a situation where shareholders are able to substitute debt for equity. This is because, where there is proportionality, the level of debt in a company does not change shareholders’ exposure to the risk of holding equity in the company or shareholders’ overall return. Due to the ability to structure an arrangement to achieve this outcome without explicit proportionate debt, the test is structured to cover transactions that may not have proportionate debt but can still be considered the result of acting together.

Prepayments of interest

A transitional prepayment rule prevents a company effectively continuing the previous non-imposition of NRWT beyond application of the new rules by prepaying interest on a financial arrangement before the new rules took effect. This situation may arise when a borrower is required to withhold NRWT on interest on an arrangement that became a related-party debt when the new rules come into force but was not previously paying non-resident passive income (for example, because of the onshore branch exemption) or was paying AIL on interest to an unassociated party (for example, as part of an arrangement that is now treated as a loan from persons who are associated with the borrower because they are acting together). The prepayment rule compares the amount of interest paid with any financial arrangement deductions taken to the date the new rules apply. Any excess interest paid is treated as being paid on the first day the new rules apply and will therefore be liable for NRWT. Any AIL previously withheld on these interest payments can be refunded or transferred against an existing tax liability.

This rule is not intended to capture foreign exchange movements on arrangements denominated in foreign currencies. When an arrangement is denominated in a foreign currency both the interest payments and total expenditure should be calculated in that foreign currency and then any excess converted to New Zealand dollars using the existing rules in subpart YF of the Income Tax Act 2007.

Example 16: Prepayment rule

NZ Co is owned 25 percent each by four non-resident private equity funds. NZ Co has been making interest payments to each fund of $100,000 per year and paying $2,000 of AIL on each interest payment. As NZ Co knows its owners will be treated as acting together when the new rules apply to their interest payments after 1 April 2017 they agree that on 1 January 2017 NZ Co will make a one-off interest payment to each fund of $800,000 with no further interest payments until after 1 April 2027. NZ Co pays $16,000 of AIL on each of these payments in its January 2017 AIL return. On 1 April 2017 it is calculated that interest payments exceed deductions by $700,000 for each fund; therefore, NZ Co is treated as paying $700,000 to each fund on 1 April 2017 and only $100,000 to each fund on 1 January 2017. $70,000 of NRWT is required to be paid on behalf of each fund. NZ Co can apply to the Commissioner to have $14,000 of AIL refunded for the interest payment to each fund that is no longer treated as being paid on 1 January 2017.

Interest payments by a member of a registered banking group

For a New Zealand bank that is part of a wider worldwide banking operation, there are commercial reasons why the New Zealand bank may borrow from its parent or another associated entity. This can include the better credit rating held by the larger parent, economies of scale of a single funding operation and/or better name recognition of the parent, which allows funding to be raised more cheaply.

It can reasonably be considered that funding on-lent to a New Zealand bank by its parent is ultimately largely borrowed from unrelated parties and not generally provided by the parent bank’s shareholders as a substitute for equity.

As the offshore and onshore branch exemptions have been restricted, New Zealand banks can no longer rely on these structures to remove their NRWT liability.

In the absence of further changes, New Zealand banks would have had a tax incentive to raise all funding from third parties so that AIL could be paid instead of NRWT even when, in the absence of tax, it would be economically efficient to borrow through an associated party.

Changes to section RF 12(1)(a)(ii) allow a member of a banking group to pay AIL on interest payments to an associated non-resident. These changes have not been extended to non-banks, including other businesses operating in the financial sector. This is because, unlike other industries, banks already have a clear definition which removes boundary issues and provides confidence that related-party funding is not an economic substitute for equity investment. This is consistent with other legislation where New Zealand-registered banks are subject to more rigorous thin capitalisation requirements and greater regulatory oversight by the Reserve Bank of New Zealand, than other financial sector taxpayers.

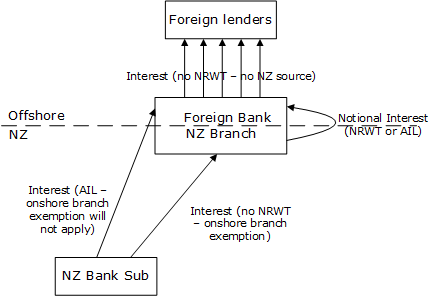

BRANCH LENDING CHANGES

A number of amendments have been made to the NRWT rules and the source rules that ensure that interest payments from a New Zealand resident (or a New Zealand branch of a non-resident) to a non-resident are subject to NRWT or AIL irrespective of whether that funding is channelled through a branch or an entity that has a branch. This ensures that funding transactions that are economically equivalent have a consistent tax treatment.

Offshore branch exemption

Changes to the source rules apply NRWT or AIL to an interest payment from the offshore branch of a New Zealand resident to a non-resident to the extent that the offshore branch lends money to New Zealand residents.

Onshore branch exemption

Changes to the NRWT rules apply NRWT or AIL to an interest payment from a New Zealand resident (or New Zealand branch of a non-resident) to a non-resident if that non-resident has a New Zealand branch, unless the interest is derived by the New Zealand branch. These changes do not apply to a New Zealand resident (or New Zealand branch of a non-resident) that pays interest to a non-resident that they are not associated with and that has a New Zealand branch that holds a banking licence.

Onshore notional loans

New subpart FG and changes to the NRWT rules apply NRWT or AIL (to the extent it was not already) to a notional interest payment from a New Zealand branch of a bank to its head office. This interest payment will be equal to the amount already included in the branch’s financial statements and claimed as a deduction against New Zealand income of the branch.

Application date

For existing arrangements, the branch amendments apply to interest payments on or after the date shown in the table below. For all other arrangements, the branch amendments apply to interest payments on or after the day the bill was enacted, being 30 March 2017.

| Scenario | Borrower | Lender | Application date for existing arrangements | Intended regime |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Onshore branches | ||||

| Related party | NZ Corporate | Foreign associate with NZ Branch | Royal assent | NRWT |

| Intra-bank Group | NZ Bank Sub | Foreign parent with NZ Branch | Income years five years after Royal assent | NRWT or AIL |

| Intra-bank Entity | NZ Bank Branch | Foreign head office | Income years two years after Royal assent | NRWT or AIL |

| Corporate | NZ Corporate including NZ Bank | Third Party with NZ Branch | Income years five years after Royal assent | NRWT or AIL |

| Third party bank | NZ borrower | Foreign bank with NZ Branch | No change | Net income tax |

| Offshore branches | ||||

| Wholesale funding | NZ Bank Sub branch | Third parties or Foreign parent | Income years five years after Royal assent | NRWT or AIL |

The ability for a member of a banking group to pay AIL on an interest payment to an associated party applies from the date of enactment, being 30 March 2017.

Further detail is provided on application dates under Key features below.

Key features

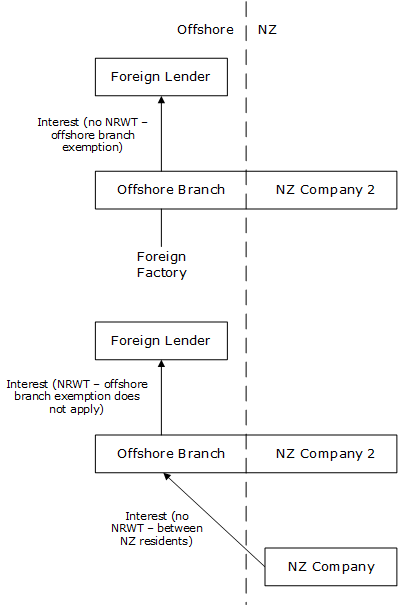

Offshore branch exemption

NRPI includes only income that has a New Zealand source. One of the exclusions from having a New Zealand source is the offshore branch exemption.

This exemption is intended to apply to a New Zealand resident operating an active business through a branch in another country. If that offshore branch borrows money to fund its offshore operations, the interest on this funding should not be subject to NRWT. This treatment ensures that the offshore branch of a New Zealand company does not have to pay NRWT when a foreign incorporated subsidiary borrowing for an equivalent business would not have to.

However, this exemption previously applied when a New Zealand company set up an offshore branch that borrowed money for the purpose of providing funding to New Zealand borrowers, who may have been associated or unassociated with the New Zealand company.

The amendments result in an interest payment by an offshore branch of a New Zealand resident to a non-resident having a New Zealand source to the extent that the branch lends to New Zealand residents.

Application of offshore branch exemption

(Full size | SVG source)

It is possible for an offshore branch of a New Zealand resident to have a business that includes lending to New Zealand residents and other business conducted outside New Zealand. In this instance, any interest payments by the branch are apportioned based on the proportion of branch assets that are financial arrangements producing New Zealand-sourced income. De minimis provisions in section YD 5(6) and (7) apply when assets deriving New Zealand-sourced income are less than 5% or more than 95% of a branch’s assets.

To ensure that interest payments by an offshore branch are appropriately subject to New Zealand tax, section 86IC of the Stamp and Cheque Duties Act 1971 has been inserted to make the payment of AIL mandatory on relevant interest payments unless NRWT is withheld.

Grandparenting of the offshore branch exemption

The changes to the offshore branch exemption apply to interest payments on arrangements entered into before the enactment of the bill on 30 March 2017 after a grandparenting period of five complete income years post-enactment. This reflects that these offshore branches have entered into commercial arrangements, frequently with unassociated parties, for terms that usually do not exceed five years, and that have been ultimately used to fund New Zealand borrowing, which is also often at fixed interest rates.

All other interest payments by offshore branches apply the new rules from the date of enactment, being 30 March 2017.

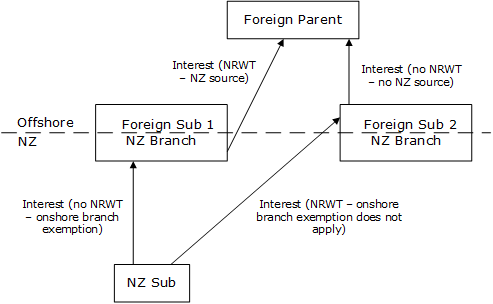

Onshore branch exemption

New Zealand-sourced interest income derived by a non-resident was not previously NRPI when the non-resident lender was engaged in business in New Zealand through a fixed establishment in New Zealand. This exemption from NRPI is known as the “onshore branch exemption”.

This exemption applied irrespective of whether the lending was made through the New Zealand branch. As with the New Zealand branch income, this non-branch (but New Zealand-sourced) income is subject to New Zealand net income tax. This means it was possible for a non-resident parent to lend money to its New Zealand subsidiary with no tax payable on the interest (other than income tax on a very slim margin). The parent could simply lend the money to the head office of a non-New Zealand group company which had a New Zealand branch. The head office of that company could then lend the money to a New Zealand group company.

The following diagrams illustrate the new rules.

The onshore branch exemption has been narrowed so that it only applies to interest payments derived by the New Zealand branch of a non-resident.

Application of onshore branch exemption

(Full size | SVG source)

One exception to this is that the onshore branch exemption continues to apply to loans not made by the onshore branch if the non-resident lender has a New Zealand branch that holds a banking licence and is not associated with the borrower. This is mainly to minimise compliance costs for individual borrowers who were not previously, but would otherwise be, required to withhold NRWT or pay AIL on interest payments to foreign banks for mortgages over foreign properties.

Application of onshore branch exemption to borrowing from foreign banks

(Full size | SVG source)

Grandparenting of the onshore branch exemption

When a New Zealand resident, other than a registered bank or certain securitisation vehicles, is borrowing from an associated non-resident that has a New Zealand branch, these amendments came into force on the date of enactment, being 30 March 2017.

When the New Zealand resident is borrowing from an unassociated non-resident that has a New Zealand branch, or when the borrower is a bank or certain qualifying securitisation vehicles, these changes will apply after a grandparenting period of five years. This is because these are, directly or indirectly, with unrelated parties and reflect arm’s-length transactions that are frequently entered into for longer terms.

This grandparenting applies to interest payments by securitisation vehicles that are a trustee of a trust that, as its core business:

- has no trust property other than financial arrangements and property incidental to financial arrangements; and

- has total debt that is sourced from another securitisation vehicle, a person who is not associated with the trustee, or an authorised deposit-taking institution regulated by the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority; and

- provides funds, directly or indirectly, only to a resident who is not associated with the trustee, unless the association arises because the resident, or another person associated with them, is a settlor of the trust as an incident of the arrangement.

These criteria ensure that the grandparenting only applies to securitisation vehicles that, as their core business, borrow money from third parties or Australian authorised deposit-taking institutions (such as banks) to on-lend to unassociated New Zealand residents.

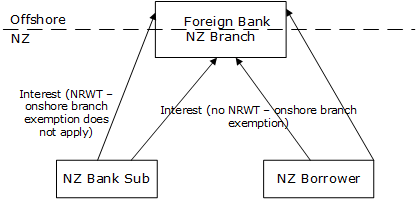

Onshore notional loans

The amendments equalise the tax treatment between foreign banks that channel offshore funding through their New Zealand subsidiaries and foreign banks that channel offshore funding through their New Zealand branches. In both cases the subsidiary and the branch can claim a deduction for an interest expense on funding provided by their foreign operations (a notional interest expense in the case of the branch). But whereas the subsidiary has always had to pay NRWT (or AIL going forward under other amendments discussed above) on its interest payment, the branch previously paid neither because there is no actual interest flow to the extent that its payment is to head office rather than to a separate company (because it is not possible for one part of an entity to make a legally recognised payment to another – the “payment” is merely a movement of funds).

This was an inconsistent result and had the potential to distort behaviour. Australia has rules which are similar, in substance, to the changes. The Australian rules apply a 5% withholding tax to a notional interest payment by a branch to its head office.

An amount that the head office makes available to the branch, that is recorded in the branch’s accounting records, is a notional loan from the head office to the branch. When the branch is allowed a deduction as an interest payment on that notional loan it will be a notional interest payment that can be subject to NRWT or AIL. NRWT or AIL will be calculated on an accrual basis to match that already calculated by the banks for financial reporting and income tax purposes.

When a foreign-owned bank borrows specifically to fund its New Zealand operations through a New Zealand branch any interest payments have always had a New Zealand source and been subject to NRWT or AIL. Accordingly, these interest payments are removed from the notional loan changes so they are not subject to NRWT or AIL twice.

Like the offshore branch changes discussed above, these notional interest payments will require AIL to be paid if NRWT is not withheld.

Interest on notional loans is deemed to be paid on the last day of the third month following an income year. This period matches the period within which the interest charge must be calculated for non-tax reporting purposes.

If a subsequent transfer pricing adjustment reduces the income tax deduction available for a notional loan new section 86GB(1)(b) will also reduce the AIL liability by the same amount.

New treatment of notional loans

(Full size | SVG source)

Grandparenting of the notional loan changes

A degree of grandparenting is appropriate as these notional loans have been used to provide funding at fixed rates to New Zealand borrowers. However, unlike the offshore branch exemption and onshore branch exemption changes discussed above, funding allocated to the New Zealand branch cannot be identified from a specific loan that may have a fixed maturity date (otherwise it would already be subject to NRWT/AIL). These rules will therefore apply to existing arrangements after a grandparenting period of two years.

Example 17: Notional loans

UK Bank, which has a 31 December balance date, is registered with the Reserve Bank of New Zealand for operations through its New Zealand branch. On 1 January 2017 UK Bank allocates NZ$1 billion of funding to its New Zealand branch. This funding is provided for a term of five years at a fixed interest rate of 5%.

Inland Revenue has reviewed this funding and did not identify any significant mispricing, and has rated the transaction for transfer pricing purposes as a low risk. Accordingly UK Bank’s NZ Branch will include $50 million of interest expenditure in its financial statements and income tax returns for the years ended 31 December 2017 to 31 December 2021.

As this transaction was entered into prior to the enactment of the new rules it will qualify for the two year grandparenting. Therefore the notional loan changes will apply to the loan from 1 January 2020. Before 31 December 2020 UK Bank’s NZ Branch registers as an approved issuer (if they were not already) and provides a completed IR 397 form to treat the loan as a registered security.

UK Bank’s NZ Branch is treated as paying NZ$50 million of interest on a registered security to UK Bank on 31 March 2021 (for the year ended 31 December 2020) and 31 March 2022 (for the year ended 31 December 2021). It includes $50 million of interest payments and $1 million of approved issuer levy in its AIL returns for the 31 March 2021 and 31 March 2022 periods.

[1] See, for example, sections EX 20B and EX 20C in the CFC rules and sections FE 5, FE 6B, FE 13, FE 14, FE 15 and FE 18 in the thin capitalisation rules.

[2] The exception to this is the de minimis test in section RF 2C(3), which includes foreign exchange movements to minimise compliance costs for borrowers determining whether the de minimis applies.