Closely held companies

A special report from Policy and Strategy, Inland Revenue. April 2017.

Closely held companies

- Look-through company eligibility criteria

- Look-through company entry tax

- Deduction limitation rule

- Debt remission

- Qualifying companies – continuity of ownership

- Ex-qualifying companies and inter-corporate dividend exemption

- Tainted capital gains

- RWT on dividends

- PAYE on shareholder-employee salaries

This special report provides information on changes to the tax rules for closely held companies contained in the Taxation (Annual Rates for 2016–17, Closely Held Companies, and Remedial Matters) Bill introduced in May 2016 and enacted in March 2017.

Information in this special report precedes full coverage of the new legislation that will be published in a future edition of the Tax Information Bulletin.

The amendments in the Taxation (Annual Rates for 2016–17, Closely Held Companies, and Remedial Matters) Act 2017 aim to simplify the rules and reduce compliance costs, while ensuring that the rules remain robust and in line with intended policy.

Closely held companies typically have just a few shareholders but can have widely varying net worth and business focus. They also make up a significant proportion of the total number of companies in New Zealand. Many use the standard company tax rules but there are also specific tax rules available for very closely held companies, in particular, the look-through company (LTC) rules and their predecessor, the qualifying company (QC) rules.

The LTC and QC rules recognise that companies are taxed differently from individuals and it is important that this tax difference does not influence business decisions on whether to incorporate as this may impede growth. For example, a business may start off as a sole trader and, as it grows, decides to become a company, given the legal benefits of limited liability. The LTC rules, in effect, enable individual tax treatment to continue to apply to owners’ LTC interests even though the LTC is legally a company for other than tax purposes. On the other hand, it is important that these rules be available only to those that could have genuinely alternatively operated through direct ownership.

The Taxation (Annual Rates for 2016–17, Closely Held Companies, and Remedial Matters) Act 2017 makes a number of changes to the LTC rules, QCs and, through a number of changes to the dividend rules, other types of companies.

The key changes relate to the following:

LTCs

- eligibility criteria;

- entry tax;

- the deduction limitation rule; and

- debt remission.

QCs

- continuity of ownership; and

- ex-qualifying companies and the inter-corporate dividend exemption.

Other companies

- tainted capital gains;

- resident withholding tax on dividends; and

- the taxation of shareholder-employees’ employment income.

Application dates

Most of the proposed changes apply from the beginning of the 2017–18 income year, or 1 April 2017, although some, such as those relating to debt remission, have been backdated where appropriate.

LOOK-THROUGH COMPANY ELIGIBILITY CRITERIA

Sections YA 1 and HZ 4E of the Income Tax Act 2007

Several amendments have been made to tighten the LTC eligibility criteria to ensure that LTCs operate as closely controlled companies, as originally intended. The changes relate in particular to who can have an interest in a LTC and how the five or fewer “counted owners” test applies. The changes are as follows:

- The way that beneficiaries are counted when determining whether the counted owner test is met has been broadened.

- Charities and Māori authorities are precluded from being LTC owners, directly or indirectly, subject to certain exemptions and grandparenting provisions.

- Trusts that own LTCs are precluded from making distributions to corporate beneficiaries.

- The foreign income that a foreign-owned LTC can earn annually is limited.

- The restriction that requires a LTC to have only one class of shares has been relaxed.

A transitional rule applies so that LTCs that will lose their LTC eligibility as a result of these amendments can convert to ordinary companies without any immediate tax consequences.

Background

The eligibility criteria limit the type of entity that can elect to become, and continue to be, a LTC as well as the type of owner that can hold LTC interests. They serve to ensure that the use of the LTC rules is appropriately targeted according to the policy intent. That is, that the rules should only be available to those that could have genuinely alternatively operated through direct ownership. That implies that ownership is held by a few shareholders; LTCs are not designed to be widely held entities. Accordingly the rules require LTCs to have no more than five counted owners to ensure that the company is “closely controlled” by individuals, and the rules specifically limit the number of owners to five look-through owners.

The concern covers not only direct ownership but also indirect ownership through benefiting from a distribution from a trust that has an ownership interest in a LTC. For example, the previous rules allowed for charities and Māori authorities to hold LTC interests, either directly or indirectly through a trust. Both charities and Māori authorities have potentially wide pools of beneficiaries and are therefore, conceptually, not part of the LTC target group.

Likewise, other amendments primarily focus on strengthening the rules supporting the requirement for a LTC to have no more than five counted owners.

Corporate ownership is precluded, given the scope that it would allow for widely held ownership. Another LTC can be an owner but is “looked through” to its owners for the purposes of determining whether the maximum of five counted owners test is met.

However, this prohibition on corporate ownership was previously undermined by allowing indirect corporate ownership through trusts.

Family trusts can be owners but specific rules determine the extent to which the trustee(s) and beneficiaries are counted owners. The previous rules were considered to be too narrow in that not all beneficiaries were taken into account.

Other new rules deal with concerns about LTCs being used by non-resident owners as conduits for investment outside of New Zealand.

No change has been made to the rule that states that if a LTC fails to satisfy the eligibility criteria during an income year it loses its LTC status from the beginning of that income year.

Key features

The definition of “look-through counted owner” in section YA 1 provides the mechanism for counting owners when testing whether the entity has met the requirements of having five or fewer counted owners. The amendments introduce a new limb to the definition with respect to LTCs owned by trusts to broaden the way that beneficiaries are counted, by including any beneficiary who receives any distribution from any source from the trust.

The definition of “look-through company” has also been amended to preclude charities and Māori authorities from becoming LTC owners (either directly or indirectly through a trust). The new restrictions do not however apply to Māori authorities and charities with existing ownership interests in LTCs that are, in effect, grandparenting structures or arrangements that were in place as at the date of the Bill’s introduction (3 May 2016).

To ensure the prohibition on charity ownership does not inadvertently discourage charitable giving, a new rule allows trusts that own LTCs to continue making distributions to beneficiaries that are charities, so long as the distribution is akin to a donation or is received by the charity as a residual beneficiary of the trust.

To bolster the existing legislative prohibition on direct corporate ownership of LTCs, the definition of “look-through company” has been further amended to prohibit a trust that owns a LTC from making any distributions to any corporate beneficiaries.

LTCs are not intended to be conduit vehicles for international investment by non-residents whereby funds are invested through New Zealand rather than into New Zealand. To restrict the use of LTCs in this conduit manner, the foreign income that can be earned by a LTC that is controlled by foreign LTC holders is now limited to the greater of $10,000 and 20 percent of the LTC’s gross income in the relevant income year. A definition of “foreign LTC holder” provides the rule for determining how the foreign ownership of LTCs is tested when applying the new foreign income restriction. It is defined as “ownership interest held more than 50% by non-residents”.

An amendment to the definition of “look-through interest” enables LTCs to have more than one class of shares. This amendment will enable LTCs to have shares carrying different voting rights, provided all shares have uniform entitlements to all distributions.

A transitional rule applies so that LTCs that will lose their LTC eligibility as a result of these amendments can convert to ordinary companies without any immediate tax consequences. This means that the “exit tax” (deemed realisation of assets and liabilities) will not arise for these LTCs and any unrealised revenue account gains will not be realised for owners at that stage.

Application dates

All the amendments, except the foreign income restrictions, apply for the 2017–18 and later income years.

The amendments to limit the foreign income of foreign-controlled LTCs apply for income years beginning on or after 1 April 2017. This means that for taxpayers with early balance dates, the foreign income restrictions apply for the 2018–19 income year.

Detailed analysis

Counting beneficiaries of trusts

Previously, for LTCs owned by trusts, when determining the number of look-through owners, the rules counted the trustee (grouping multiple trustees as one) when the LTC income earned by the trust was not fully distributed to beneficiaries, as well as all beneficiaries who had received LTC income from the trust as “beneficiary income” in the current and preceding three years. This was too narrow.

Accordingly, the definition of “look-through counted owner” has been amended to count all distributions to beneficiaries, irrespective of whether they are from the LTC or from other sources, or whether they are received by the beneficiary as beneficiary income, trustee income, trust capital or corpus[1]. The amendment is necessary to ensure the test counts all persons who, though they may not receive beneficiary income, nevertheless benefit from the trust owning LTC shares. Including all distributions is also necessary to ensure the rule is not undermined by the fungibility of money, which makes the result from tracing the source of a distribution arbitrary.

Transitional rule

To ensure the revised distributions rule applies only prospectively, the time period over which distributions are measured has not been changed. The counted owner test continues to look back to the current and preceding three income years. A transition rule will apply over the next four years which involves applying both tests depending on the relevant time periods involved. The strengthened test will only apply to income earned from the beginning of the 2017–18 income year. Income earned and distributed to beneficiaries or retained by the trust prior to the 2017–18 income year will be counted under the old test.

Those entities that were LTCs in the 2016–17 income year will (with all other things being equal) retain their LTC status if:

- they continue to meet the current test over the three to four-year measurement period; and

- having applied the new test (measuring distributions made only from the beginning of the 2017–18 income year) to establish whether there are any additional counted owners; and

- in aggregate, there are a maximum of five look-through counted owners.

This means that for the 2017–18 income year a person would look at distributions provided between the 2014–15 income year to the 2016–17 income year and apply the old test which looks at income sourced from a LTC interest to determine whether any beneficiaries are look-through counted owners. The person would then apply the new rule for any distributions in the 2017–18 income year to determine whether there are any additional look-through counted owners.

The legislation is expressed in terms of “persons” rather than counted owners so there is no double counting of the same person if they receive a counted distribution prior to 2016–17 as well as a distribution after the 2016–17 income year.

For the 2018–19 income year the person would look at distributions provided in the 2015–17 income years and apply the old test and then look at distributions in the 2017–19 income years and apply the new test.

The transition is summarised in the following table:

| For income year | Which test to apply | Previous year 3 | Previous year 2 | Previous year 1 | Current year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017–18 | Old test | 2014–15 | 2015–16 | 2016–17 | - |

| New test | - | - | - | 2017–18 | |

| 2018–19 | Old test | 2015–16 | 2016–17 | - | - |

| New test | - | - | 2017–18 | 2018–19 | |

| 2019–20 | Old test | 2016–17 | - | - | - |

| New test | - | 2017–18 | 2018–19 | 2019–20 | |

| 2020–21 | Old test | - | - | - | - |

| New test | 2017–18 | 2018–19 | 2019–20 | 2020–21 |

To ensure the strengthened test incorporating all distributions to beneficiaries does not result in double counting of owners, under the new rules trustees are only look-through counted owners when no beneficiaries of the trust are look-through counted owners.

Example

A LTC is 100 percent owned by a Trust A. Trust A has five listed beneficiaries. From 1 April 2017 to 31 March 2020 the trust has made no distributions to any of the beneficiaries.

As a result, for the 2019–20 income year, none of the five beneficiaries are look-through counted owners. As the trust has no beneficiaries as look-through counted owners, the trustee is a look-through counted owner and the LTC has a total of one look-through counted owner for the income year.

Example

A LTC is 100 percent owned by Trust A. In the 2016–17 income year, Trust A made distributions to 10 beneficiaries that were from non-LTC sourced income.

In the 2017–18 income year, these 10 beneficiaries will not be look-through counted owners as distributions in the 2016–17 are considered under the old rules which do not consider distributions of non-LTC sourced income. If there are no other distributions the trustee will be a counted owner in these circumstances.

Example

A LTC is 100 percent owned by Trust B.

Trust B has made the following distributions:

- 2015–16 income year: Distribution of LTC-sourced income to two beneficiaries.

- 2016–17 income year: Distribution of non-LTC sourced income to two beneficiaries.

- 2017–18 income year: Distribution of non-LTC sourced income to two beneficiaries.

- 2018–19 income year: No distributions to date.

All of the beneficiaries are separate individuals.

For the 2018–19 income year, the LTC will have four look-through counted owners. This is made up of the two beneficiaries who received distributions in the 2015–16 income year and the two beneficiaries who received distributions in the 2017–18 income year.

The two beneficiaries who received distributions in the 2016–17 income year are not look-through counted owners as distributions for the 2016–17 income year are counted under the old rules which do not consider distributions of non-LTC sourced income.

Corporate beneficiaries

Under the previous rules, a trust that owned a LTC interest could have a corporate beneficiary but direct ownership by companies, other than other LTCs, was expressly prohibited. The trust was looked through and the shareholders of the corporate beneficiary counted if it received any beneficiary income. This, coupled with the way that the number of owners was determined for trusts, unintentionally provided widely held non-LTC corporates with a way to circumvent the prohibition on direct ownership. This could be used to obtain inappropriate tax advantages.

The definition of “look-through company” has been amended to expressly prohibit trusts that own LTCs from making distributions to corporate beneficiaries either directly or indirectly.

This approach in effect allows for grandparenting of current structures involving corporate beneficiaries, by not expressly prohibiting LTC-owning trusts from having corporate beneficiaries (so long as the trust does not make further distributions to the company) while strengthening the prohibition on ownership of LTCs by standard companies.

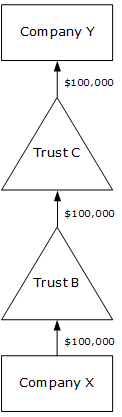

Example: Indirectly a beneficiary of the trust

(Full size | SVG source)

- Trust B is a shareholder of Company X.

- Trust C is a beneficiary of Trust B.

- Company Y is a beneficiary of Trust C.

Company X makes a distribution to Trust B. Trust B then passes on the distribution to Trust C who passes it to Company Y.

Company X will be ineligible to be a LTC. This is because a trustee shareholder of Company X has made a distribution of income to a company that is indirectly a beneficiary of the trust.

Voting rights

Previously, in order to simplify the attribution of a LTC’s income and expenditure to its underlying owners, LTCs could only have one class of share. This rule was overly restrictive as it could limit legitimate commercial structuring or generational planning and inhibit some companies from becoming LTCs.

Accordingly, the requirement has been relaxed through amending the definition of “look through interest”. The amendment allows a LTC to have shares that carry different voting rights provided that all shares still have the same rights to distributions.

Charities and Māori authorities

To ensure that the LTC rules are reserved for closely controlled entities, amendments have been made that extend the trust approach of looking through to the ultimate beneficiaries to LTCs owned by tax charities (as defined in the Income Tax Act) and Māori authorities. The amendments effectively preclude direct ownership by charities and direct or indirect ownership by Māori authorities. There are however some exceptions to this.

“No strings attached” distributions to charities

An amendment to the definition of “look-through company” allows distributions by LTCs or shareholding trusts of LTCs to charities which have no influence over the LTC or shareholding trust. This enables genuine gifts from LTCs or shareholding trusts to be made to charities and recognises that many LTCs may want to make charitable distributions.

Grandparenting existing Māori authorities and charities

The amendments provide grandparenting for existing Māori authority and charity interests in LTCs through the definitions of “grand-parented charity” and “grand-parented Māori authority.

This will enable these entities to avoid the compliance cost of converting their LTC interests to limited partnerships, which are another look-through vehicle that is often used to achieve the same outcome as a LTC.

The amendments only enable Māori authorities and charities to hold interests in LTCs which they had an interest in prior to 3 May 2016 (the date of introduction for the Taxation (Annual Rates for 2016–17, Closely Held Companies, and Remedial Matters) Bill)[2]. This means that Māori authorities and charities can change the amount of shareholding they have in LTCs they had an interest in prior to 3 May 2016, but cannot acquire interests in new LTCs that they did not have an interest in before that date.

Example

Charity X is a tax charity which, on 15 April 2015, acquired a 50 percent shareholding in Widgets Ltd. On 1 April 2016 Widgets Ltd elected to become a LTC.

On 2 May 2017, Charity X increased its shareholding in Widgets Ltd to 100 percent.

As Charity X acquired its interest in Widgets Ltd before 3 May 2016, its interests in Widgets Ltd. are grandparented and Widgets Ltd can maintain its LTC status despite Charity X’s ownership interest. The increase in shareholding by Charity X on 2 May 2017 also does not affect the LTC status of Widgets Ltd, due to the grandparenting.

Foreign income restrictions

Although LTCs are envisaged primarily as a structure for domestically focused companies, under the previous rules there were no restrictions on either foreign investment by LTCs or on LTCs having non-resident owners. This combination unintentionally allowed for LTCs to be used as conduit investment vehicles – that is, New Zealand domiciled vehicles used by non-residents to invest in foreign markets generating income generally not taxable in New Zealand. This gave rise to reputational risks for New Zealand.

To address these risks, amendments have been made to the definition of “look-through company” to restrict the amount of foreign income that a foreign-controlled LTC (a LTC that is more than 50 percent held by non-residents) can derive.

The amendments provide that a company is ineligible to be a LTC if both:

- more than 50 percent of the total ownership interest in the company is held by foreign LTC holders (as defined); and

- the entity has foreign-sourced amounts for the income year that in total are more than $10,000 and 20 percent of the company’s gross income for the year.

The thresholds are intended to provide flexibility for some degree of combined non-resident shareholding and foreign income, and should prevent a domestic family business inadvertently falling outside the rules through an owner emigrating. On the other hand, the amendment is intended to prohibit LTCs being used by non-residents purely as conduit investment vehicles.

Definition of “foreign LTC holders”

The rule tests foreign control by looking at the direct and indirect ownership of the LTC, and testing the tax residence of the owners. Standard tests of residency will apply to determine the residency of individuals.

A trust that has foreign settlors is considered to be a foreign LTC holder only to the extent of the proportion of the value of settlements made by the non-resident settlors. For example, if a trust held 50 percent of the shares in a company, and 50 percent of the value of settlements made on the trust were by non-residents, then 25 percent of the ownership interests in the company would be considered to be held by foreign LTC holders. In determining the proportion of the value of settlements made by non-resident settlors, provisions of services at below market value are not counted. These services are not counted due to the difficulty in valuing them.

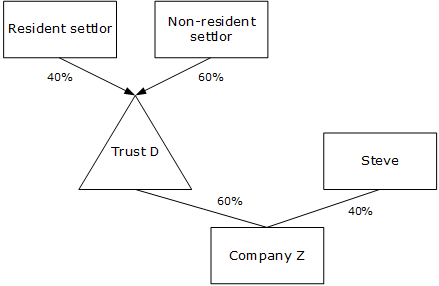

Example

(Full size | SVG source)

Company Z has two shareholders, Trust D which has a 60 percent shareholding in Company Z and Steve, who holds a 40 percent shareholding.

Steve is an individual who is resident in New Zealand.

Trust D is a trust which received $100,000 in cash settlements, $60,000 of the settlements were made by a non-resident settlor and $40,000 were made by a resident settlor. Trust D’s 60 percent shareholding in Company Z is therefore split between treated as being held by non-residents and residents on a 36:24 basis.

Overall, 36 percent of Company Z’s shares are considered to be held by foreign LTC holders and 64 percent (40 percent and 24 percent) held by residents. Because of this, the foreign income restrictions will not apply to Company Z.

Transitional rule

Section HZ 4E provides a transitional rule for companies that will lose LTC status as a result of the amendments to the eligibility criteria for LTCs. Section HB 4(6) provides that these LTCs will be able to transition to being ordinary companies without triggering the exit adjustment requirements in section HB 4(6).

This transitional rule applies when an entity is a look-through company at the end of the 2016–17 income year and ceases to be a LTC because of one of the eligibility changes referred to above.

In this situation the section provides that section HB 4(6) does not apply. Section HB 4(6) ordinarily treats a LTC that transitions to an ordinary company as selling all of its assets to a third party at market value and then reacquiring them as an ordinary company. This results in a realisation of any revenue account gains on the LTC’s assets, which becomes income of the owners.

Instead section HZ 4E provides that the company is treated as having the same tax position it had as a LTC. This means that any assets of the LTC are transferred at book value, and the company is treated as having acquired them on the same date as the LTC and with the same intention.

Example

Speculator Ltd is a LTC that is involved in property renting and speculation. On 1 May 2015, Speculator Ltd acquired land for $500,000 with the intention of reselling. Speculator Ltd sells the land on 5 August 2020 for $700,000.

On 1 June 2017, Speculator Ltd. made a distribution to a corporate beneficiary. As a result, Speculator Ltd will lose LTC status as a result of the eligibility changes in the new rules.

When Speculator Ltd becomes an ordinary company it will be treated as having acquired the land on 1 May 2015 for $500,000 and with the intention of resale. Any increase in the value of the property will not be realised upon Speculator Ltd exiting the LTC rules. Instead any revenue account gains will be brought to account when Speculator Ltd actually sells the land – in this case on 5 August 2020 – realising a $200,000 revenue account gain.

LOOK-THROUGH COMPANY ENTRY TAX

Sections CB 32C, HB 13, OB 6, RE 2 and YA 1 of the Income Tax Act 2007

Amendments to section CB 32C have been made, which modify the income adjustment calculation (commonly known as the entry tax) done when a company converts to a LTC to ensure that:

- the taxable income that arises to LTC owners as a result of the calculation is taxed at each shareholder’s personal tax rate; and

- for QCs converting to LTCs, that the entry tax formula does not tax owners of QCs any more than they would be if they liquidated before the conversion.

An associated amendment to section HB 13 clarifies that a company that elects to become a LTC effectively steps into the shoes of the company it converted from and must use the tax book values of the company at the time of entry for all purposes under the LTC rules.

Background

The LTC entry tax adjustment applies when a company elects to become a LTC. It triggers a tax liability on un-imputed retained earnings by deeming the company to have been liquidated immediately prior to conversion. This adjustment is intended to ensure that reserves that would generate taxable income for shareholders if distributed before entering the LTC regime and that would be able to be distributed tax-free once the company becomes a LTC, are taxed to owners at the time of entry.

The tax rate used in the old formula was 28%, which means that no further tax was paid on the company’s retained earnings. The 28% rate was used in the formula to reduce compliance costs, but this could provide a tax advantage for shareholders whose top personal tax rate exceeded 28% (that is, those on the 30% or 33% marginal tax rate) as well as a disadvantage for shareholders whose personal tax rates were below 28%.

Further, the entry tax formula applied to tax all un-imputed retained earnings except eligible capital profits. For QCs that elected into the LTC rules, this meant tax was charged to the extent that the earnings were not eligible capital gains. This approach was inconsistent with the QC rules, which allow for tax-free distribution of un-imputed earnings as exempt dividends to QC shareholders. As a result, the entry tax formula could over-charge tax on the un-imputed reserves, which may have deterred some QCs from converting to LTCs.

Key features

A revised formula treats the resulting income that flows through to the LTC owners as a dividend, with imputation credits attached where available, thereby ensuring that the income is taxed at the owners’ personal tax rates in all cases.

This overcomes a problem with the previous formula, which based the calculation on the company tax rate and could lead to under- or over-taxation, depending on an owner’s marginal tax rate.

A further formula covers situations when a QC has insufficient tax credits to cover distributions of all reserves.

An amendment also clarifies that the tax book value of assets and liabilities of a company that elects into the LTC regime become the opening book values for the LTC, for the avoidance of doubt. For example, revenue account property transfers at tax book value, and not market value, meaning that unrealised gains and losses are not recognised at that point.

The amendment also clarifies that the LTC has the same status, intention and purpose in respect of its assets, liabilities and associated legal rights and obligations. For example, if a company acquired land on 8 August 2017 with an intention of resale and subsequently converts to a LTC, the LTC will be treated as also acquiring the land on 8 August 2017 with an intention of resale.

Application date

The amendments apply for the 2017–18 and subsequent income years.

Detailed analysis

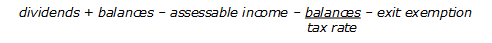

The current formula in section CB 32C(5) is:

where:

dividends is the sum of the amounts that would be dividends if, immediately before becoming a LTC, the property of the company, other than cash, were disposed of at market value, the company met all its liabilities at market value and it was liquidated, and the net cash amount was distributed to shareholders without imputation credits or foreign dividend payment credits attached. In other words a liquidation took place;

balances is the sum of the balances in the imputation credit account and foreign dividend payment credit account immediately before becoming a LTC, plus amounts of income tax payable for an earlier income year but not paid before the relevant date, less refunds due for the earlier income year but paid after the relevant date;

assessable income is the amount of income that would arise as a result of liquidation less any deductions that the company would have as a result of liquidating. This includes depreciation gains or losses, bad debts and disposals of revenue account property;

tax rate is the company tax rate in the income year before the income year in which the company becomes a LTC;

exit exemption is the exit dividends that, if the company had previously been a LTC and is now re-entering the LTC rules, would be attributed to any retained reserves from the previous LTC period that have not since been distributed.

The new formula in section CB 32C(4) is:

(untaxed reserves + reserves imputation credit) × effective interest

where:

reserves imputation credit is the total amount of credits in the company’s imputation account, up to the maximum permitted ratio for the untaxed reserves under section OA 18 (Calculation of maximum permitted ratios) and is treated as an attached imputation credit included in the dividend calculated;

effective interest is the person’s effective look-through interest for the look-through company on the relevant day; and

untaxed reserves is calculated using the following formula:

dividends – assessable income – exit exemption

where:

dividends is the sum of the amounts that would be dividends if the following events occurred for the company or the amalgamating company, immediately before it became a look-through company or amalgamated with a look-through company:

(i) it disposed of all of its property, other than cash, to an unrelated person at market value for cash; and

(ii) it met all of its liabilities at market value, excluding income tax payable through disposing of the property or meeting the liabilities; and

(iii) it was liquidated, with the amount of cash remaining being distributed to shareholders without imputation credits attached;

assessable income is the total assessable income that the company would derive by taking the actions described in subparagraphs (i) and (ii) above; less the amount of any deduction that the company would have for taking those actions;

exit exemption is the amount given by the formula in section CX 63(2) (Dividends derived after ceasing to be a look-through company), treating the amount as a dividend paid by the company for the purposes of section CX 63(1), if section CX 63 would apply to a dividend paid by the company.

The terms “dividends, “assessable income” and “exit exemption” are therefore the same as in the previous formula.

This proposed formula will treat the retained income and imputation credits that would arise on liquidation of the company as being distributed to the individual LTC owners who will need to include the income and imputation credits in their return of income. This approach leaves it to each individual shareholder to determine what tax rate applies to their share of the income, and results in a fairer tax outcome.

The formula will apply to companies converting to LTCs, including QCs with sufficient imputation credits to fully impute the dividend, as well as companies that amalgamate with LTCs. However, it will not apply to those QCs converting to LTCs for which the entry tax formula would result in a dividend which is not fully imputed.

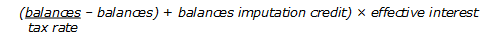

Qualifying companies with limited imputation credits

Instead the proposed additional formula in section CB 32C(8) is to be used to calculate the entry tax payable when a dividend by a QC on liquidation would be only partially imputed and, therefore, only partially a taxable distribution. The proposed formula in this case is:

where:

balances is the sum of the following amounts:

(i) the balance in the company’s imputation credit account;

(ii) an amount of income tax payable for an earlier income year but not paid before the relevant date, less refunds due for the earlier income year but paid after the relevant date;

tax rate is the basic tax rate for the income year of the company that contains the relevant day;

balances imputation credit is the same as the amount of the item balances, and is treated as an attached imputation credit included in the dividend calculated;

effective interest is the person’s effective look-through interest for a look-through company on the relevant day.

Benchmark dividends

An amendment to section section OB 61 (ICA benchmark dividend rules) ensures that the dividend which results from the entry tax formula is disregarded for the purposes of the benchmark dividend rules. This amendment is for the avoidance of doubt that the level of imputation attaching to the entry tax deemed dividend does not require a benchmark dividend ratio change declaration as the company is not an imputation credit account (ICA) company as defined in section OB 1 of the Income Tax Act at the time that the dividend arises.

Example

X Co is an ordinary company. It has two shareholders: Amy, who has 40 percent of the shareholding in X Co, and Ben, who holds 60 percent of the shareholding in X Co.

$500,000 of equity was put into X Co, which X Co used to purchase a $500,000 house it acquired with the intention of resale. The house is now worth $700,000. X Co also has $72,000 of retained earnings and $28,000 of imputation credits from rent received from the house.

X Co converts to a LTC. As a result, an entry tax calculation is required. The formula is:

(untaxed reserves + reserves imputation credit) × effective interest

The reserves imputation credit is $28,000. Amy’s effective interest is 40 percent and Ben’s effective interest is 60 percent.

Untaxed reserves

Untaxed reserves are calculated using the formula:

Dividends – assessable income – exit exemption

The dividends are the amounts that would be dividends if X Co sold its $700,000 house, then liquidated. If X Co liquidated it would have $272,000 of dividends, being the $700,000 cash from the property, the $72,000 of retained earnings, minus the subscribed capital of $500,000.

The assessable income of X Co would be $200,000, being the total assessable income that X Co received from the sale of the house (as it was held on revenue account).

The exit exemption would not apply as X Co has not previously been a LTC.

As a result, the untaxed reserves are $72,000.

As a result, the entry tax calculations are:

Amy: (72,000 + 28,000) × 0.4 = $40,000

Ben: (72,000 + 28,000) × 0.6 = $60,000

These are treated as dividends and imputation credits may be attached to them. Amy may have up to $11,200 of imputation credits attached, and Ben may have up to $16,800 of imputation credits attached.

DEDUCTION LIMITATION RULE

Sections GB 50 and HB 11 of the Income Tax Act 2007

The coverage of the deduction limitation rule, which limits a LTC owner’s LTC deductions to the amount that they have economically at risk, has been restricted to LTCs in partnership or joint venture.

To bolster the other rules in the Income Tax Act that help to stop LTC owners claiming excessive deductions, the existing anti-avoidance rule that deems a partner’s transactions to be at market value has been extended to owners of LTCs.

Background

The deduction limitation rule was designed to ensure that LTCs cannot be used to generate deductions in excess of the money that owners have at risk in the company. It was based on a comparable rule that applies to limited partnerships. It works by restricting an owner’s ability to use LTC deductions against their other income when the deductions are greater than the owner’s economic contribution to the LTC (referred to as “owner’s basis”).

The rule results in undue compliance costs in many cases, as it requires each LTC owner to calculate their “owner’s basis” annually, which requires owners to keep track of what they have invested in and withdrawn from the business, and all income and expenditure attributed to them while they have been an owner. Over time this would require LTC owners to maintain records well beyond the standard record-keeping period for tax information. Furthermore, each owner must complete the calculation even though most will not have their deductions constrained by it because their share of net expenditure is less than their owner’s basis.

Overall, given that this rule results in compliance costs that appear to outweigh the benefits provided from the operation of the rule, the rule is largely unnecessary in the LTC context. However, for LTCs working together in partnership or as a joint venture, the rule has relevance. This is because partnerships and joint ventures of LTCs are in many respects an alternative to limited partnerships where a deduction limitation rule is appropriate. They can also be potentially widely held vehicles.

The removal of the rule for other LTCs is considered appropriate, given that the risk of LTCs being used to generate excessive deductions is ameliorated by other rules in the Income Tax Act, including the general and specific anti-avoidance provisions and the debt remission amendments discussed in the following item.

Key features

The first amendment means that the deduction limitation rule in section HB 11 will not apply for most LTCs. The provision will be changed to specifically cover only LTCs that are in partnership or are members of a joint venture under section HG 1. The formula determining the “owner’s basis” in section HB 11 will otherwise be unchanged, although officials are continuing to explore options for simplifying and clarifying the formula.

For those no longer covered by the rule, deductions previously restricted and carried-forward by the rule will be automatically freed up from the 2017–18 income year, and will be available for offsetting against their income from that year onwards.

The specific anti-avoidance rule in section GB 50 has been extended to LTCs and their owners. The rule is designed to ensure that transactions between partners and their partnerships that have the effect of defeating the rules in sub-part HG (joint ventures, partners and partnerships) are treated as taking place at market value.

Application date

The amendment to section HB 11 applies from the beginning of the 2017–18 income year.

The amendment to section GB 50 applies from 1 April 2017.

DEBT REMISSION

Sections DB 11, EW 31, EW 39, HZ 8 and YA 1 of the Income Tax Act 2007

Amendments to the debt remission rules have been made to deal with specific concerns about the way the rules work in relation to LTCs and partnerships.

Background

Debt arrangements with owners

Debt remission, being the extinguishing of a debtor’s liability by operation of law or forgiveness by the creditor, gives rise to debt remission income to the debtor under the financial arrangement rules. Under current tax law, debt remission produces taxable income to the debtor.

Problems arise from the interaction of the LTC (and partnership) rules with the financial arrangement rules that produce remission income in circumstances when, as a result of the transparency of the LTC or partnership, the debt is effectively self-remitted. When an owner of a LTC remits debt owed to them by the LTC, all the LTC owners derive debt remission income given the look-through nature of a LTC. This includes the owner that remitted the debt who is required to pay tax on their share of the remission income despite making an economic loss (to the extent of the portion of the loan that is attributed to the other shareholders). Generally, they are unable to claim a deduction for the bad debt. Overall, this results in over-taxation of the owner who remitted the debt, which is not an appropriate policy outcome.

Market value of debts

The other change amends the LTC rules to clarify that when calculating the market value of an owner’s interest as debtor in a financial arrangement with a third party, the amount of any adjustment for credit impairment must be taken into account. This clarification is necessary as Inland Revenue officials have become aware of certain interpretations being taken to the contrary.

The amendment will ensure that the debt remission rules apply as intended so that debt remission income arises when a LTC is either liquidated or elects out of the LTC rules. This is important given the proposed limiting of the scope of the deduction limitation rules, as the debt remission rules are one of the backstops in the Income Tax Act that help to preclude excessive deductions.

Key features

The first amendment ensures that remission income does not arise to either a LTC owner or a partner who remits a debt owed to them (referred to in the amendment as “self-remission”) by the LTC or partnership, including a limited partnership. This also applies when an owner effectively remits the debt through an entity ceasing to be a LTC or similar deemed disposals of owners’ interests.

The second clarifies that in respect of a debt owed by a LTC to a third party, the market value of the debtor’s interest in the debt is adjusted for any credit impairment. While this was always the intention, some practitioners have argued otherwise.

Both amendments are necessary to ensure that the debt remission rules operate as intended.

Any refunds of overpaid tax as a result of the retrospective application can be claimed by taxpayers reopening past returns, but we do not anticipate many will need to do this. Any additional income that may arise as a result of retrospective application will only need to be brought to account in the 2017–18 income year (a transitional amendment achieves this).

Application dates

The first amendment to remission income applies to income years beginning on or after 1 April 2011, the start date of the LTC rules.

The second amendment to the valuation of credit impairment applies from 1 April 2011. However, to avoid reopening past returns, any additional income and associated penalties and interest from those earlier years is brought to account in 2017–18 income returns.

Detailed analysis

Debt remission

The new Act amends the financial arrangement rules to exclude self-remission by a shareholder of a LTC or a partner in a partnership. This is achieved by introducing the concept of a “self-remission” into the Act and enabling the shareholder or partner who has lent money to a LTC or partnership a deduction equal to their proportion of debt remission income of the LTC or partnership.

Section EW 31(11) has been amended so that the definition of “amount remitted” excludes a “self-remission”. “Self-remission” is defined as an amount of remission for a person and a financial arrangement under which, and to the extent to which, because of the operation of sections HB 1 or HG 2 (which relate to LTCs and partnerships), the person is also liable as debtor in their capacity of owner or partner.

This exclusion means that a shareholder or partner of a LTC or partnership will have a negative base price adjustment in their capacity as a creditor that neutralises out any income attributed to them as debtor in their capacity as owner or partner.

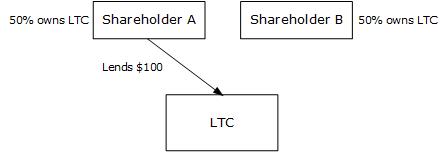

Example

(Full size | SVG source)

A LTC is 50 percent owned by two shareholders – Shareholder A and Shareholder B. Shareholder A lends $100 to the LTC. Shareholder A subsequently remits the $100 debt it owes to the LTC.

As a result of the remission both Shareholder A and the LTC need to make a base price adjustment (BPA).

LTC’s base price adjustment

The base price adjustment formula is:

Consideration in – consideration out – income + expenditure + amount remitted

The LTC has received $100 in consideration and as a result its BPA is a positive amount of $100.

This $100 is attributed equally to the two shareholders under the LTC look through rules in section HB 1. As a result, Shareholder A has income of $50 and Shareholder B has income of $50.

Shareholder A’s base price adjustment

Consideration in – consideration out – income + expenditure + amount remitted

Shareholder A has paid out consideration of $100 and has made a debt remission of $100. However, $50 of this debt remission is a “self-remission” under the amendments to section EW 31 as they are also liable as a debtor in their capacity as an owner of a LTC.

As a result, Shareholder A has a negative base price adjustment of $50.

Shareholder A is entitled to a deduction for this negative base price adjustment under section DB 11(1B) up to the amount of the self-remission ($50).

As a result, Shareholder A has income of $50 attributed from the LTC and a deduction of $50 and as a result has no net income from the remission. Shareholder B has income of $50 attributed from the LTC.

An amendment has been made to section EW 8 to allow taxpayers to treat arrangements that are excepted financial arrangements under section EW 5(10) as financial arrangements. This applies to persons who have made an interest-free loan in New Zealand currency that is repayable on demand. The ability to treat the loan as a financial arrangement enables a person who loans money to a LTC to get the benefit of the self-remission amendments when it would ordinarily be unavailable due to the loan being an excepted financial arrangement under section EW 5(10).

Disposals of financial arrangements

An equivalent amendment has been made to section EW 39 to ensure that the same result is achieved in circumstances when a LTC owner or a partner in a partnership dispose of their interests in the financial arrangement. For a LTC this can occur upon permanent cessation, capital reduction, or revocation of LTC status. For partnerships this can occur on sale of partnership interests by a partner or upon dissolution of a partnership.

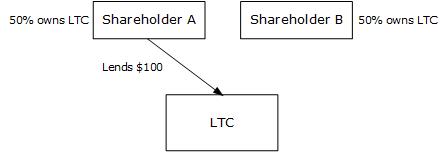

Example

(Full size | SVG source)

A LTC is 50 percent owned by two shareholders – Shareholder A and Shareholder B. Shareholder A lends $100 to the LTC.

The LTC becomes insolvent and cannot repay its debts. As part of a restructure the shareholders decide to convert the LTC to an ordinary company and as a result a base price adjustment is required for both the LTC and Shareholder A.

Base price adjustment for LTC

Similar to the previous example, the LTC has income of $100 which is attributed equally to Shareholder A and Shareholder B.

Base price adjustment for Shareholder A

Consideration in – consideration out – income + expenditure + amount remitted

Under the old section EW 39, Shareholder A would be treated as having been paid the full market value of the $100 debt as if the LTC was not insolvent.

Under the amendment to section EW 39, Shareholder A may subtract the amount of “self-remission” from this market value. As a result, shareholder A is treated as having been paid $50 for the debt.

As a result, Shareholder A has a negative base price adjustment of $50, which offsets the $50 of remission income so that its net income is $0.

Shareholder B on the other hand has income of $50 from its share of the remission income.

Market value of an owner’s interest as a debtor

An amendment to section HB 4 has been made that clarifies that when calculating the market value of an owner’s interest as a debtor in a financial arrangement, the amount of any adjustment for credit impairment must be taken into account. This ensures the debt remission rules work as intended so that when a debtor sells their interest in a financial arrangement that they will not be able to repay in full, they are treated the same as if the amount they are unable to repay was remitted.

Determining the amount of credit impairment

Under the new rules, debtors will not need to rely on information from the creditor to determine the amount of credit impairment. Instead, the debtors will need to make a fair and reasonable estimate of the credit impairment based on the information they have available.

To determine the credit impairment, the key question to ask is “if the LTC was sold or liquidated, how much of the debt would be repaid to the creditor?” In most cases, determining this would involve looking at the balance sheet of the LTC to determine the net assets of the LTC.

Example

Tara sets up a LTC to hold a rental investment property. The LTC gets a mortgage of $500,000 to finance the purchase of the property. The LTC has no insurance for the property.

Due to flooding, the rental property declines in value to $300,000. The LTC also has $50,000 in cash reserves. The only liability of the LTC is the mortgage which still has $500,000 outstanding.

Tara decides to liquidate the LTC. In determining the market value of the mortgage, Tara must ask “if the LTC was sold or liquidated, how much of the debt would be repaid to the creditor?” As the LTC has $350,000 in assets and no other liabilities other than the mortgage, the answer to this question is $350,000. When making the base price adjustment, this is the value of the arrangement for the LTC to use.

Transitional rule for market value amendment

A transitional rule ensures that any income that would have arisen in earlier income years through the retrospective application of this remedial clarification will be recognised prospectively in the 2017–18 tax year. This will reduce the consequences for taxpayers who should have had income arise in line with the intended operation of the disposal rules but who took a different tax interpretation and avoids the need to reopen past returns.

The formula under the transitional rule in section HZ 8 is:

retrospective amount – current amount

where:

retrospective amount is the amount of income, for the person’s owner’s interest in financial arrangements as debtor, that would result from the application of section HB 4 for income years before the 2017–18 income year, treating that section as amended by the clarification that the market value of the interest must take into account the amount of any adjustment for credit impairment, for those income years;

current amount is the amount of income, for the person’s owner’s interest in financial arrangements as debtor from the application of section HB 4 that the person returned for income years before the 2017–18 income year.

QUALIFYING COMPANIES – CONTINUITY OF OWNERSHIP

Sections HA 6 and YA 1 of the Income Tax Act 2007

An amendment to the qualifying company (QC) rules provides that qualifying company status will cease if there is a change in control of the company.

Background

Qualifying companies are partial look-through vehicles that allow for the profits of the company to be taxed in the same way as a standard company but, unlike a standard company, capital gains and un-imputed dividends can be distributed tax-free to shareholders during the course of business. QCs in place when the new LTC regime came into force on 1 April 2011 were allowed to continue, pending an ultimate decision on the future of QCs. There are still around 70,000 QCs.

As part of the Government’s decisions from the review of closely held company taxation, it was confirmed that these QCs could continue. Requiring all remaining QCs to convert to LTCs, or failing that to ordinary companies, would not only impose significant compliance costs on those businesses but would also not be practical as the LTC requirements might not be suitable for many QCs.

This means that while no new QCs can be created, existing QCs can continue until they are either liquidated, elect out of the QC regime or fail to meet the QC eligibility criteria. In effect, this provides the grandparented QCs with some degree of permanent tax advantage, due primarily to the opportunity for tax deferral on income through the taxing of the income in the first instance at the company rate, which is often lower than the top personal rate, or the favourable treatment of capital gains relative to ordinary companies.

The effective limitation on trading of QCs by ensuring that QC status is lost if there is a change in control of the company, supports the 2010 decision to grandparent QCs. This outcome ensures that existing QC owners are able to make some shareholder changes without sacrificing QC status while preventing the current owners from trading any tax advantage.

Key features

A change of control will be measured using a continuity test. The new shareholder continuity limitation in section HA 6 of the Income Tax Act requires a “minimum continuity interest” of at least 50 percent for the “QC continuity period”. The continuity period will extend from the date of Royal assent (30 March2017) to the last day in the relevant income year. The “minimum QC interest” is defined to mean the lowest voting interest or market value interest during the continuity period.

A breach of this requirement will trigger the loss of QC status under the standard QC rules.

To ease compliance, the continuity test will apply prospectively to changes in shareholding from the date of enactment (30 March 2017).

Exceptions

For the purposes of the shareholder continuity measurement, changes to shareholding resulting from property relationship settlements or the death of a shareholder will be ignored when measuring a change of control.

In addition, transfers between close relatives are ignored when measuring a change in control. The amendments achieve this by treating shares that have been transferred to a close relative as being held by a single notional person.

For this purpose “close relative” is defined as a spouse, civil union partner or de facto partner of the person or a person who is within the second degree of relationship to the person.

Example

A QC has two shareholders: Tara, who holds 40 percent of the shares in the QC and Uri, who holds 60 percent of the shares in the QC.

Uri transfers his shares in the QC to Velma, his daughter. Velma then transfers half of her 60 percent shareholding to Walter, her spouse.

As the transfers between Uri, Velma and Walter have all been between close relatives they are treated as being held by a single notional person and so will not affect the QC continuity test.

Application date

The amendments apply for the 2017–18 and later income years.

EX-QUALIFYING COMPANIES AND INTER-CORPORATE DIVIDEND EXEMPTION

Sections CW 14 and HA 17 of the Income Tax Act 2007 and sections HG 10 and HG 10B of the Income Tax Act 2004

An amendment has been made to limit the scope of section CW 10, which prevents companies that were once qualifying companies from utilising the inter-corporate dividend exemption.

Background

When the qualifying company regime was being considered, the Consultative Committee on the Taxation of Income from Capital (the Valabh Committee) recommended that qualifying companies not be able to utilise the inter-corporate dividend exemption. This was intended to prevent ordinary companies from providing exempt dividends to qualifying companies, which could then be distributed tax-free to shareholders due to qualifying companies being able to pay un-imputed dividends tax free.

The Valabh Committee also recommended that companies that had previously been qualifying companies should similarly not be able to utilise the inter-corporate dividend exemption.

This was because there is a potential avoidance risk through a QC creating capital gains through revaluing the shares they hold in a non-qualifying company. These capital gains can be passed to shareholders as exempt dividends and funded by a loan back to the QC. If the QC then converts to an ordinary company, the company can, if the inter-corporate dividend exemption is available, receive an exempt dividend from other companies in a wholly owned group, which could be used to repay the loan from the shareholder without a tax cost.

However, this rule extends too far and prevents the use of the inter-corporate dividend exemption in circumstances when the avoidance risks are minimal. As a result, amendments have been made to limit the scope of the rule.

Key features

Amendments to sections CW 14 and HA 16 have been made so that the inter-corporate dividend exemption is available to companies that have previously been qualifying companies when either:

- the dividend is derived at least seven years after the company ceased to be a qualifying company; or

- the company never paid an un-imputed dividend while it was a qualifying company.

The amendment is retrospective to the 2005–06 income year. To achieve this, corresponding amendments to sections HG 10 and HG 10B of the Income Tax Act 2004 have been made.

Application date

The amendment applies for the 2005–06 and later income years.

TAINTED CAPITAL GAINS

Sections CD 44 and CZ 9B of the Income Tax Act 2007

The scope of the “tainted capital gains” rule is being narrowed to address a previous overreach of the rule, and make it much more targeted.

Specifically, the rule will only apply to asset sales between companies that have at least 85 percent common ownership, with the original owners still retaining at least 85 percent interest in the asset at the time of liquidation. Previously, the rule applied to any associated party transactions.

Background

Capital gains derived at the company level cannot be distributed tax-free by ordinary companies, except upon liquidation. Previously the tainted capital gains rule (in section CD 44(10B) of the Income Tax Act) taints a capital profit if it was realised through a sale of a capital asset to an associated person, making the gain taxable when distributed to shareholders in a liquidation. There was one exception to the rule which applies to gains derived by a close company (as defined in section YA 1) that arise during the course of liquidation.

The policy rationale for the previous rule was that sales of assets between associated persons (for example, sales within a group of companies) could be for the purposes of creating additional amounts of capital reserves for tax-free distribution, rather than for general commercial reasons. The concern was that this would allow a company to distribute “capital profits” tax-free in lieu of dividends, which would have been taxable.

The rule had its origins in the mid-1980s when some companies were selling assets to associated companies to generate capital gains that they could at the time use to pay out tax-free dividends. Major changes to tax settings since then, in particular the introduction of the imputation regime and a comprehensive definition of what is a “dividend”, made the rule less relevant.

In practice, the previous rule could capture genuine transactions when the sale was not tax driven – for example, the transfer of an asset as part of a genuine commercial restructure. The restriction, therefore, extended beyond its intended ambit and applied to gains made on sales to any associated party, not just an associated company. Companies could often be inadvertently caught by the rule, resulting in their being unable to be subsequently liquidated without a tax impost.

The rule still has a role in the case of sales between companies that have significant commonality of ownership, where it provides protection against arrangements that are in effect in lieu of a taxable dividend. The rule has, therefore, been confined to such instances.

Key features

The previous rule and exception relating to capital gains (and capital losses) made on asset sales between associated companies (sections CD 44(10B) and (10C)) have been replaced with a rule that measures commonality of ownership interest both at the time the asset is sold and at the time of the liquidation distribution.

A capital gain or capital loss amount will not arise (in other words, the amount is tainted) if:

(i) at the time of disposal, a group of persons holds, in relation to the seller company (company A) and the buyer company, common voting interests or common market value interests of at least 85 percent; and

(ii) on the liquidation of company A, the company that owns the asset is company A or, if it is not company A, the percentage given by the following formula is 85 percent or more:

commonality interest × ownership interest

where:

commonality interest is the percentage of common holding by a group of persons, for the owning company and company A, of common voting interests or common market value interests (if they are greater than the common voting interests);

ownership interest is the percentage of ownership of the asset, by market value, for the owning company.

For example, an asset of a company (company A) may be sold to another company (company B) in the same wholly owned group for a capital gain and at a later stage be on-sold to a non-associated company for a further capital gain, with both companies being liquidated. Both gains will be non-taxable as the outcome of the series of transactions is that by the time of the liquidation distribution the asset has been sold to a company that has no common ownership with companies A and B.

If the owner at the time of liquidation is a non-corporate, (ii) above is not relevant (as that leg of the test requires some portion of the asset to be owned by a company). The gain or loss will, therefore, not be tainted.

The proposed threshold is set at 85 percent because a change of ownership to an unrelated third party of more than 15 percent provides sufficient assurance that the transaction is genuine and involves a real transfer of the underlying assets rather than, say being in lieu of a dividend.

Application date

The amendments come into force on the date of enactment and apply to distributions made on or after that date.

Detailed analysis

Gains prior to date of enactment

The new rules apply to liquidations of a company from the date of enactment. This means the new formula applies to capital gain or loss amounts that were made prior to the date of enactment as long as the liquidation occurred after the date of enactment.

This includes gains made between 1988 and 2010 to which the “related persons” test previously applied. To achieve this, section CZ 9B, which contains the related persons test, and section CD 44(14B), which cross-refers to section CZ 9B, have been repealed.

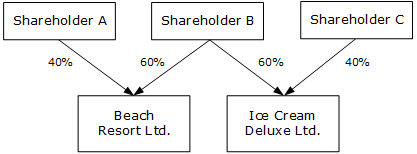

Example

(Full size | SVG source)

Beach Resort Ltd and Ice Cream Deluxe Ltd are associates due to having a shareholder with voting interests in each company of 60%. The remaining 40% of shareholdings are held by different persons for each company.

On 1 May 2005, Ice Cream Deluxe Ltd sold its ice cream cart to Beach Resort Ltd with Ice Cream Deluxe Ltd making a capital gain of $10,000 on the transaction.

On 1 September 2018, Ice Cream Deluxe Ltd is liquidated. The $10,000 capital gain is not tainted as no group of persons hold common voting interests of 85% or more in both companies.

Timing of liquidation

The second part of the test looks at the ownership of the asset “on the liquidation of company A”. The timing of this test occurs when an amount is distributed on the liquidation of the company.

Asset that has ceased to exist

If an asset ceases to exist on the liquidation, any capital gains or losses from the asset will not be tainted. This is because, at the time, no company owns the asset and so the second limb of the test above will not be met (company A will not own the asset and the ownership interest will be 0%).

Example

Company A acquires a boat for $400,000. Company A sells the boat to Company B for $500,000. Company A and Company B have common voting interests of 90%.

The boat sinks and Company B has to write off the asset as it is neither salvageable nor insured. Company A and Company B subsequently liquidate.

The $100,000 capital gain for Company A and the $500,000 capital loss for Company B will not be tainted. This is because on the liquidation, neither Company A nor Company B own the asset and the ownership interest for the asset is 0% as no one owns it.

Application date

The amendments came into force on 30 March 2017, being the date of enactment, and apply to distributions made on or after that date.

RWT ON DIVIDENDS

Sections CD 39, RD 36, RE 2, RE 13, RE 14 and RE 14B of the Income Tax Act 2007

Amendments have been made to deal with the over-taxation of certain dividends under the resident withholding tax (RWT) rules:

- The first change allows a company to opt out of deducting RWT from a fully imputed dividend paid to corporate shareholders.

- The second change provides a new formula for determining the RWT obligation when cash and non-cash dividends are paid contemporaneously.

A third amendment deals with an unintended restriction, because of the need to deduct RWT, on the rule which allows a dividend to be backdated to clear a shareholder’s current account.

Background

RWT on dividends between companies

The payment of passive income, such as dividends and interest to resident recipients is subject to an obligation to account for RWT, which is withheld by the company at the time of payment and paid to Inland Revenue in the month following payment. For dividends, a flat rate of 33% applies (less any imputation credits). For interest, the RWT rate varies according to the recipient’s personal marginal tax rate.

As a result of the lowering of the company tax rate to 28%,[3] even when a company pays a fully imputed dividend the dividend is still subject to an additional 5% RWT. For dividends paid to corporate shareholders (who will be subject to the company tax rate of 28%) this obligation to withhold RWT resulted in an initial over-taxation of these dividends.[4] Before the amendment, this over-taxation could give rise to additional compliance costs for both the paying company, which had to account for the additional RWT to Inland Revenue, and the recipient company, which was required to seek a refund when the RWT credit could not be used.

RWT on concurrent cash and non-cash dividends

When a company pays a non-cash dividend, such as a taxable bonus issue, the dividend is still subject to RWT. The non-cash dividend is required to be grossed up because the RWT cannot practically be withheld from the non-cash amount.

When a company pays a non-cash dividend concurrently with a cash dividend, both dividends are subject to RWT. Before the amendments, the two dividends were treated as separate dividends, meaning that the non-cash dividend was still subject to the gross-up even when the concurrent cash dividend was sufficient to cover the RWT obligation on both dividends. This could result in the RWT obligation across both dividends being higher than it should be.

RWT impact on backdating a dividend

Under the dividend rules, shareholders who have overdrawn current accounts at year end are treated as having received a deemed dividend based on the interest they would have had to pay if the overdrawn account had been a loan.

To simplify matters for taxpayers, the rules in sections CD 39(5) and RD 36(2)(b) were introduced, which allow a company to pay a backdated fully imputed dividend to clear, or at least reduce, an overdrawn current account. For dividends to qualify for backdating there must be no further tax owing.

The application of these rules was unintentionally limited as a result of the company tax rate changes. They technically did not work, as a dividend could only be backdated if there is no RWT obligation on the dividend and, in practice, any dividend will have a RWT obligation, even a fully imputed dividend (which had a 5% RWT obligation).

Key features

RWT on dividends between companies

An amendment has been made which limits the definition of “resident passive income” in section RE 2(5) to exclude fully imputed dividends paid to a corporate shareholder if the paying company chooses to exclude the dividend from the definition.

In effect this allows a company to opt out of withholding RWT on a fully imputed dividend paid to another company. This amendment reflects the fact that the obligation to withhold RWT on a fully imputed dividend paid to another company over-taxes the dividend.

The ability not to withhold has been made optional because for some paying companies (particularly those that are widely held) an outright requirement not to withhold RWT on fully imputed dividends may raise compliance costs. This is because they will need first to establish which shareholders are corporates and those that are not, and differentiate between these two groups within their systems.

RWT on concurrent cash and non-cash dividends

To deal with the previous potential over-taxation of cash and non-cash dividends paid contemporaneously, new section RE 14B streamlines the RWT obligations by treating the two dividends as a single dividend. The amendment introduces a new formula to calculate the amount of RWT owing on the dividends, which applies only if the cash dividend is equal to or greater than the amount of RWT payable under the formula.

Consequently amendments have also been made to sections RE 13 (Dividends other than non-cash dividends) and RE 14 (Non-cash dividends other than certain non-share issues).

RWT impact on backdating a dividend

Amendments to section CD 39(9) and RD 26(2)(b) have been made to ensure the rules work as intended. The intention is to allow for a dividend that had no further tax owing (that is, it is fully imputed) to be backdated, to expunge, or at least reduce, an overdrawn current account balance. This avoids or limits the deemed dividend arising and reduces compliance costs. However, a previous requirement was that there had to be no RWT obligation.

Taxpayers continued to use the rule but due to an oversight at the time the company tax rate was changed, it technically did not work given the need to deduct RWT. The amendment provides certainty by clarifying that the rule should apply to dividends that are fully imputed, irrespective of any RWT obligation.

Application dates

The first two amendments to enable companies to opt out of deducting RWT from fully imputed dividends paid to corporate shareholders and providing a new formula for determining the RWT obligation when cash and non-cash dividends are paid contemporaneously, apply from the date of enactment, being 30 March 2017.

The third amendment to allow dividends to be backdated applies from 1 April 2008 for the 2008–09 and subsequent income years.

Detailed analysis

Sections RE 13 and RE 14 calculate the RWT required to be withheld on cash and non-cash dividend respectively. Previously, when cash and non-cash dividends were paid contemporaneously, with the objective of the cash dividend being used to account for the RWT owing on the non-cash dividend, there was potential over-taxation because the two dividends are treated separately under these two sections.

New section RE 14B provides the payer with the option of combining cash and non-cash dividend payments and accounting for RWT as though they were a single dividend. The new section only applies when the cash dividend alone is sufficient to cover the total RWT owing, meaning that RWT will be paid by deduction rather than gross-up, and the payer has elected for the section to apply.

The amount of RWT that the payer must withhold is calculated using the following formula:

(tax rate × (dividends + tax paid or credit attached)) − tax paid or credit attached

where:

tax rate is the basic rate set out in schedule 1, part D, clause 5 (Basic tax rates: income tax, ESCT, RSCT, RWT, and attributed fringe benefits);

dividends is the total amount of the cash dividend and the non-cash dividend paid before the amount of tax is determined;

tax paid or credit attached is the total of the following amounts:

(i) if a dividend is paid in relation to shares issued by an ICA company, the total amount of imputation credits attached to the dividends;

(ii) if a dividend is paid in relation to shares issued by a company not resident in New Zealand, the amount of foreign withholding tax paid or payable on the total amount of the dividends.

To ensure there is no overlap of the rules, neither section RE 13 nor section RE 14 will apply to the dividends if the payer chooses to apply section RE 14B.

Amount of cash dividend required to satisfy the RWT liability

If a taxpayer provides a non-cash dividend and wishes to provide a cash dividend simply to satisfy the RWT liability on the non-cash dividend then the following formula provides how much cash dividend is required:

cash dividend = 0.4925* non-cash dividend – tax paid or credit attached

Example

Co. X wishes to provide a non-cash dividend of $360. The non-cash dividend has imputation credits of $140 attached. Co. X wishes to provide a cash dividend solely to satisfy the RWT liability.

cash dividend = 0.4925 * 360 – 140 = $37.30

If Co. X provides a cash dividend of $37.30, the RWT payable is also $37.30.

PAYE ON SHAREHOLDER-EMPLOYEE SALARIES

Sections RD 3, RD 3B, RD 3C and YA 1 of the Income Tax Act 2007

An amendment has been made so that shareholder-employees of close companies who receive both regular salary or wages throughout the year and variable amounts of other employment income are able to elect to split their income so that the base salary is subject to PAYE and the variable amount is paid out before tax.

Background

Shareholder-employees of close companies often do not derive regular amounts of salary or wages, or do not get paid in regular periods throughout the income year. For smaller companies, the remuneration of shareholder-employees also often depends on the performance of the business and, therefore, the annual salary will not be known until well after year end. This can make compliance with the PAYE rules difficult because the rules are designed for circumstances when employees’ salaries are known at the start of the income year and payments are made regularly (monthly, fortnightly or weekly) throughout the year.

To alleviate this problem, the previous rules allowed for shareholder-employees who do not derive regular amounts of salary or wages or who do not get paid for regular periods, to treat all amounts of income they receive through the year as not subject to PAYE, subject to certain conditions (see section RD 3). As a result, the amounts received would be taxable in the employee’s tax return and could give rise to provisional tax obligations.

The previous rules may not have adequately relieved the compliance costs incurred by shareholder-employees and may not have suited the myriad of shareholder-employee circumstances, when paying a combination of PAYE and provisional tax might have been preferable. There was no option to pay a combination of PAYE and provisional tax; the rule was all or nothing.

Key features

New section RD 3C allows for a shareholder-employee of a close company to choose to split their earnings so that the base salary is subject to PAYE and the variable amount is paid out pre-tax, and is therefore likely to be subject to provisional tax instead.

To be able to treat any payments as not subject to PAYE under these rules, the shareholder-employee must meet one of the following three requirements:

- the shareholder employee does not derive salary and wages of a regular amount for regular pay periods of one month or less; or

- less than 66 percent of their annual gross income is salary or wages; or

- an amount is paid to them as income that may later be allocated to them as an employee for the income year.

If the shareholder-employee does not meet these requirements, the full amount of payments to them are subject to PAYE.

This amendment allows additional flexibility for shareholder-employees who may be unduly constrained by the current rules.

To ensure that the ability to switch between provisional tax and the PAYE system is not used inappropriately, there are rules to prevent taxpayers “flip flopping” between the options. These rules provide that: