RIA - Hybrids/NRWT issue

| Date | 22 November 2017 |

|---|---|

| Document type | Regulatory impact assessment |

| Title | Hybrids/NRWT issue |

| Downloads | PDF - Signed (645 KB; 14 pages) |

| Contents |

IMPACT SUMMARY: HYBRIDS/NRWT ISSUE

SECTION 1: GENERAL INFORMATION

Purpose

Inland Revenue is solely responsible for the analysis and advice set out in this Impact Summary, except as otherwise explicitly indicated. This analysis and advice has been produced for the purpose of informing policy decisions to be taken by Cabinet.

Key Limitations or Constraints on Analysis

This analysis has been limited by the following factors:

- The scale of the problem (in terms of its fiscal costs) has not been accurately identified because it will depend on the behavioural response of taxpayers, which may in turn be informed by work currently being undertaken by Inland Revenue.

- No consultation with external stakeholders (including those who would be affected by the proposed action).

Responsible Manager (signature and date):

Paul Kilford

Policy and Strategy

Inland Revenue

22 November 2017

SECTION 2: PROBLEM DEFINITION AND OBJECTIVES

2.1 What is the policy problem or opportunity?

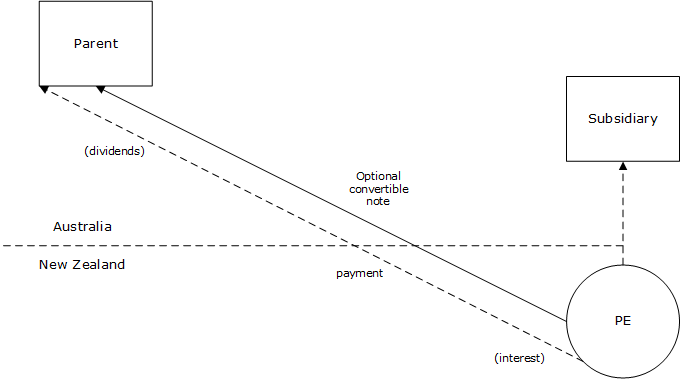

The problem identified arises only in a very specific set of fact circumstances:

- There is a New Zealand branch or “permanent establishment” (PE) of a non-resident company;

- That PE borrows money from another non-resident in the same overseas jurisdiction as the PE’s corporate residence;

- The borrowing takes place under a “hybrid” instrument which means it is treated as one form of financing (debt) by New Zealand, but another form of financing (equity) by the other country.

An example is set out in the diagram below.

(Click on the image for a full-size version | SVG source)

The view until now of Inland Revenue and many taxpayers has been that New Zealand can withhold non-resident withholding tax (NRWT) on the payments. However, some taxpayers have disputed this view and as a consequence Inland Revenue is currently reconsidering whether it is legally correct. Inland Revenue has sought Crown Law’s advice, and has indicated that it may well decide the law does not permit NRWT to be withheld. This interpretation is based on a view that the payments are dividends for the purposes of our double tax agreements (DTA).

Because double tax agreements over-ride domestic law, this view would, if adopted, mean that the taxpayer would be entitled to an interest deduction in New Zealand for the payments (because New Zealand treats the payments as interest), but the payments would not be subject to NRWT (because the other country and the DTA treat them as dividends). This is contrary to the intent of the provisions, as deductible outbound interest should always have NRWT (or its alternative, approved issuer levy (AIL)) withheld unless there is a specific exemption providing otherwise.

The hybrid mismatch measures already proposed and approved by Cabinet (and covered by the regulatory impact analysis: http://taxpolicy.ird.govt.nz/sites/default/files/2017-other-beps-20-ria-hybrids-july-2017.pdf) would ensure that payments made under such hybrids could not be both deductible in New Zealand and non-assessable overseas. In some circumstances the measures would still allow a deduction in New Zealand for the payments. However the measures do not cover whether NRWT must be withheld from such payments. Consequently, the currently proposed hybrid measures would still permit payments under a hybrid financial instrument to be deductible in New Zealand, but not subject to NRWT. This contrasts with the tax treatment of dividends, which are not deductible. It also contrasts with the tax treatment of ordinary interest, which is deductible but subject to NRWT (or AIL).

As a result of this, the currently proposed hybrid mismatch measures would remove the incentive to use these types of hybrids in most, but not all cases. The hybrids could still be attractive if the non-resident was not concerned about the assessability of the payments in its home jurisdiction. For example, if the non-resident had tax losses, was tax exempt, or simply preferred to pay tax in its home jurisdiction (as most Australian companies do due to their imputation system).

If no action is taken, Inland Revenue’s changed interpretation could therefore expose the New Zealand tax base to significant risk. It is difficult to estimate the fiscal risk, as it depends in part on taxpayers’ behaviour, and in part on whether section BG 1 would apply to counteract the arrangements (section BG 1 may apply to some arrangements but not others). The risk is in two parts: a risk that $60 million of previously paid NRWT or AIL might be refunded in the near term, and an ongoing risk that $15 million per annum of NRWT or AIL might no longer be payable. Both risks could materialise as a fiscal cost against existing baselines. Addressing the problem will increase baselines by $1 million per annum on a go forward basis, relative to the status quo.

2.2 Who is affected and how?

The only taxpayers affected are those that enter into the structure illustrated in the response to question 2.1 above. However, as far as Inland Revenue is aware, many of the taxpayers that use these structures already pay NRWT or AIL in accordance with the policy intent. As a result, for most affected taxpayers, any change in the law to align with the policy intent would only reaffirm Inland Revenue’s pre-existing legal interpretation – and so would not involve the imposition of additional tax or compliance costs compared with their current position. However, the proposed approach would stop some of these taxpayers from claiming a tax refund for the NRWT or AIL they paid in previous years if Inland Revenue’s interpretation changes. It would also stop some of them from ceasing to pay AIL or NRWT in future years.

A small number of taxpayers have disputed Inland Revenue’s current legal view and not paid NRWT or AIL. These taxpayers would be affected by the proposed change, as they would now be required to pay NRWT or AIL. However, this is the outcome we want to achieve with the proposed change, as the policy intent is for all taxpayers to be subject to NRWT or AIL on cross border deductible interest payments (unless there is a specific exemption providing otherwise).

2.3 Are there any constraints on the scope for decision making?

Limitations in respect of stakeholder engagement are set out in section 5, below.

The scope of this problem is limited by the extremely narrow fact-pattern identified.

The proposed regulatory action has two major interdependencies:

BEPS and hybrids

The current problem with the NRWT rules only arises for hybrid mismatch arrangements.

Hybrid mismatch arrangements are, broadly speaking, cross-border arrangements that create a tax advantage by exploiting differences in the tax treatment of an entity or instrument under the laws of two or more countries. The result of hybrid mismatch arrangements is less aggregate tax revenue collected in the jurisdictions to which the arrangement relates.

In July 2017 the Government announced that it would comprehensively adopt the OECD’s hybrid mismatch recommendations, with suitable modifications for the New Zealand context. In addition to the regulatory impact analysis referred to in response to question 2.1, the relevant Cabinet papers can be found at:

- http://taxpolicy.ird.govt.nz/sites/default/files/2017-other-beps-13-cabinet-paper-overview-july-2017.pdf (which covers the BEPS package more broadly); and

- http://taxpolicy.ird.govt.nz/sites/default/files/2017-other-beps-19-cabinet-paper-hybrids-july-2017.pdf (which is specific to the hybrids proposals).

The hybrids work is a relevant interdependency because it establishes that Cabinet wished to “… send the clear message that using hybrid mismatch arrangements should not produce a tax advantage …” (see paragraph 7 of the hybrids-specific Cabinet paper linked above).

Therefore, we consider that addressing the problem identified in this Impact Summary is consistent with bringing into effect the outcome clearly desired by Cabinet for hybrid mismatches.

As explained in 2.1 above, however, the existing hybrids measures still allow for cross border financial instruments to carry payments which are deductible in New Zealand, but not subject to NRWT. Accordingly, the proposed measure would supplement the existing hybrids measures by cancelling a further hybrid mismatch tax advantage.

NRWT amendments

New Zealand has recently reviewed and updated its rules related to NRWT and its alternative, AIL.

These reforms were enacted as part of the Taxation (Annual Rates for 2016–17, Closely Held Companies, and Remedial Matters) Act 2017. The relevant Regulatory Impact Statement can be found at: http://taxpolicy.ird.govt.nz/publications/2016-ris-archcrm-bill/nrwt-related-party-and-branch-lending-nrwt-changes

As set out in paragraph 26 of that document, the objective of the reforms was to “… ensure the return received by a non-resident lender from an associated borrower (or a party that is economically equivalent to an associated borrower) will be subject to NRWT and, at a time, that is not significantly later than when income tax deductions for the funding costs are available to the borrower.”

In the structure that is the subject of this Impact Summary, the potential outcome is that a taxpayer will (absent the proposed measure) be entitled to a deduction but have no corresponding NRWT liability. This is contrary to the stated policy objective.

Accordingly, the proposed measure supplements the previous NRWT amendments by ensuring that NRWT cannot be avoided for deductible interest payments on hybrid instruments.

SECTION 3: OPTIONS IDENTIFICATION

3.1 What options have been considered?

We have considered four options, three of which involve addressing the identified problem by ensuring that NRWT applies in all instances where a deduction is allowed in New Zealand for an interest expense and for this outcome to occur notwithstanding the effect of our double tax agreements (the “policy solution”). However, they differ in their proposed application date. The four options are:

- Option 1: The status quo, which would allow Inland Revenue to finalise its legal view and allow that view to prevail on all existing and future arrangements. This would likely result in the problem identified in 2.1 continuing.

- Option 2: Provide that NRWT or AIL applies to any deductible interest payment with a New Zealand source (the policy solution). The policy solution would have prospective effect.

- Option 3: Enact the policy solution retrospectively to the earliest date from which taxpayers can claim refunds for AIL or NRWT overpayments.

- Option 4: Enact the policy solution retrospectively to the earliest date from which taxpayers can claim refunds for AIL or NRWT overpayments, but also include a “savings” provision for taxpayers that have already adopted the position that NRWT or AIL is not payable prior to the Bill containing the policy solution being introduced.

Currently the potential non-applicability of NRWT or AIL arises under New Zealand’s DTAs. DTAs are incorporated into New Zealand law under the Income Tax Act 2007, which states that DTAs have effect notwithstanding any other provision of that Act (subject to some exceptions). Accordingly, the policy solution would need to expressly override our DTAs in the amending legislation. We note that Australia already has a rule that legislates the policy solution, including an express DTA override.

Criteria

The four options are assessed in this Impact Summary against the following criteria:

- Economic efficiency - the tax system should, to the extent possible, apply neutrally and consistently to economically equivalent transactions. This means the tax system should not provide a tax preferred treatment for one transaction over another similar transaction or provide an advantage to one business over another. This helps ensure that the most efficient forms of investment which provide the best returns to New Zealand as a whole are undertaken. At the same time there is a concern that taxes should not unduly raise the cost of capital and discourage inbound investment.

- Fairness - the options should ensure that the law is seen as treating people fairly and consistently and should not allow people to avoid their tax obligations (including any foreign tax obligations).

- Integrity of the tax system – the options should collect the revenue required in a transparent and timely fashion while not providing opportunities for tax avoidance or arbitrary tax reductions

Analysis

In the following options analysis, an option having a fiscal risk is seen as a negative. However, this will not automatically disqualify the option. There are times when changing the law will have a fiscal cost or risk for the Government, but this is nevertheless desirable because of the gains in one or more of the other assessment criteria.

Option 1 – not preferred

We consider that the policy solution is preferable to the status quo.

The status quo will likely mean that a PE would be entitled to an interest deduction in New Zealand for payments on certain hybrid instruments (as the payments are characterised as “interest” under New Zealand domestic law), but the payments would not be subject to NRWT (as the payments are characterised as “dividends” under the DTA). This is contrary to the intent of the relevant DTA provisions, as outbound interest, which is deductible in determining the profits of a PE, should always have NRWT withheld unless there is a specific exemption providing otherwise (e.g. the sovereign wealth fund exemptions provided in some of our DTAs). It also exposes the New Zealand tax base to a fiscal risk, as it allows a deduction from New Zealand tax for a payment without a corresponding tax liability for the recipient. Accordingly, the status quo negatively affects the integrity of the tax system.

The general anti avoidance rule in section BG 1 might still apply to some of the arrangements using these kinds of hybrid instruments, in which case NRWT or AIL would still need to be paid. However, there is a high risk that section BG 1 would not apply to other arrangements we are aware of.

In addition, the status quo option negatively affects both fairness and economic efficiency. This is because it would give a competitive advantage to a multinational firm that uses the relevant funding structure over a domestic firm or another, more compliant, multinational. This is contrary to the objectives of the BEPS work more generally and the hybrids project in particular.

Under the status quo option, Inland Revenue’s changed interpretation could expose the New Zealand tax base to significant risk. It is difficult to estimate the fiscal risk, as it depends in part on taxpayers’ behaviour, and in part on whether section BG 1 would apply to counteract the arrangements (section BG 1 may apply to some arrangements but not others). The risk is in two parts: a risk that $60 million of previously paid NRWT or AIL might be refunded in the near term, and an ongoing risk that $15 million per annum of NRWT or AIL might no longer be payable. Both risks could materialise as a fiscal cost against existing baselines. Addressing the problem will increase baselines by $1 million per annum on a go forward basis, relative to the status quo.

Option 2 – not preferred

This option would address the policy issue identified in 2.1. It would also have advantages in terms of fairness, economic efficiency and the integrity of the tax system compared with the status quo option (by eliminating the status quo’s disadvantages in these regards). However, these advantages would only arise for future income years. Taxpayers who used the relevant hybrid structure in previous income years may be entitled to request a refund of the NRWT or AIL they previously paid.

We consider that it would be unfair to allow taxpayers to claim refunds of their previously paid AIL or NRWT in these circumstances. It would also reduce the integrity of the tax system. It is clear that NRWT / AIL was intended to be payable on cross border interest payments. This was also Inland Revenue’s interpretation of the law until now, which was followed by many taxpayers. The ability of some taxpayers to avoid NRWT AIL through the use of a hybrid instrument is a clear loophole in the current rules, and taxpayers aware of the issue would have perceived it as such. Accordingly, we consider there should be no legitimate expectation for taxpayers to obtain a refund for any AIL or NRWT previously paid in respect of these hybrid instruments.

We estimate that there is a potential one-off fiscal risk of $60 million under this option. This is because taxpayers that are known to use this structure may be able to obtain refunds of their previously paid AIL/NRWT under this option if Inland Revenue changes its current legal interpretation (and the previously paid NRWT or AIL has been included in the fiscal baseline),.

This option would also give rise to a potential $1 million per annum fiscal benefit compared with the current baseline. This is because taxpayers in active disputes would be required to pay $1 million of NRWT in future tax years if the policy solution was implemented (and this $1 million has not been included in current fiscal baselines).

Option 3 – not preferred

Option 3 would address the policy issue in 2.1. As a retrospective measure, it would also stop taxpayers from claiming a refund for any previously paid NRWT or AIL. Accordingly, it is preferable to option 2 as it has advantages in terms of fairness, economic efficiency and integrity of the tax system, over the status quo option in respect of both future and past income years. This option also has the lowest potential fiscal risk of all the options (equal with option 4).

This option also has the largest potential fiscal benefit. This is because, in addition to the fiscal benefit of option 2 in respect of future income years, this option would also require the taxpayers that have disputed Inland Revenue’s current legal interpretation to pay NRWT in respect of past tax years in the event that Inland Revenue’s current legal interpretation changes. This NRWT has not been included in the current fiscal baselines. Accordingly, this gives rise to an additional potential one-off fiscal benefit of approximately $5 million.

However, this option would also retrospectively change the law for those taxpayers who have already taken the position that NRWT or AIL was not payable and entered into disputes with Inland Revenue. This would be fair, as different taxpayers in the same position would be treated the same. In addition, excluding taxpayers who have taken an aggressive tax position from the retrospective application of the rules seems to reward them for their aggressive behaviour.

However, there is a wider issue of legal certainty involved. If Parliament retrospectively changes a law taxpayers have relied on, then this means taxpayers can never fully rely on the law (as stated at the time) in any dispute with the Government. This would erode the integrity of the tax system from a wider perspective. It would also erode perceptions of fairness, in that the Government might be perceived as misusing its legislative power to win a dispute with taxpayers.

Option 4 – preferred

This option addresses the policy problem set out in 2.1. It also has fairness, economic efficiency and integrity of the tax system advantages over the status quo option in respect of both future and past income years. Although this option is slightly less fair than option 3, it best supports the integrity of the tax system. This is because it prevents taxpayers from claiming refunds for previously paid NRWT or AIL, while preserving the legal position of taxpayers that previously adopted the position that NRWT or AIL was not payable prior to the introduction of the Bill containing the policy solution.

This option would also give rise to a potential fiscal benefit of $1 million per annum compared with current baseline. This is because taxpayers that are still disputing Inland Revenue’s current position would be required to pay $1 million of NRWT in future tax years (and this $1 million has not been included in current fiscal baselines).

We note that this option does have a smaller potential fiscal benefit than option 3, as it does not require taxpayers disputing Inland Revenue’s current legal interpretation to pay NRWT in respect of past tax years. We estimate the reduced potential fiscal benefit to be approximately $5 million.

3.2 Which of these options is the proposed approach?

We consider Option 4 to be the best option. This option addresses the policy problem set out in 2.1. It also has advantages, in terms of fairness, economic efficiency and the integrity of the tax system, over the status quo option in respect of both future and past income years. Although this option is less fair than option 3, it best supports the integrity of the tax system. This is because Option 4 prevents taxpayers from claiming refunds for previously paid NRWT or AIL, while preserving the legal position of taxpayers that previously adopted the position that NRWT or AIL was not payable prior to the introduction of the BEPS Bill. Accordingly it addresses the policy problem without the drawbacks of options 2 and 3.

Option 4 also has the lowest equal fiscal risk. However, it lacks Option 3’s potential one-off $5 million fiscal benefit. Even so, we consider the lack of this fiscal benefit is outweighed by the importance of protecting the integrity of the law from a wider perspective.

SECTION 4: IMPACT ANALYSIS (PROPOSED APPROACH)

4.1 Summary table of costs and benefits

| Affected parties (identify) | Comment: nature of cost or benefit (eg ongoing, one-off), evidence and assumption (eg compliance rates), risks | Impact $m present value, for monetised impacts; high, medium or low for non-monetised impacts |

| Additional costs of proposed approach, compared to taking no action | ||

| Regulated parties | The proposed approach removes the ability of taxpayers to avoid NRWT or AIL for future periods. It does not change the previously adopted position for past periods. We are aware of several taxpayers who have entered into the hybrid structure set out in 2.1. We have calculated the fiscal costs based on these taxpayers. If there are further taxpayers, then the impact will be increased. We do not expect there to be other taxpayers with a significant value of such hybrid structures, but we cannot confirm this. We note that many taxpayers already pay NRWT and AIL under the current rules. Accordingly the proposed approach will not increase their costs compared with their current position. However it will deprive them of a future cost saving if compared with the status quo option if Inland Revenue changes its legal view. |

A potential $16m per annum cost arising from additional NRWT or AIL for future years compared with doing nothing if Inland Revenue changes its legal view. A potential one off $60m cost arising from the denial the NRWT or AIL refunds which taxpayers may be entitled to for past years if Inland Revenue changes its legal view and no action is taken. |

| Regulators | No material administrative costs for Inland Revenue. | - |

| Wider government | No costs. | No costs |

| Other parties | Not applicable | Not applicable |

| Total Monetised Cost | For regulated parties, a potential cost of 16m of NRWT or AIL per annum plus a potential cost of $60m in respect of possible refunds for past years compared with doing nothing. | |

| Non-monetised costs | None we are aware of. | None |

| Expected benefits of proposed approach, compared to taking no action | ||

| Regulated parties | The regulated parties will be required to pay NRWT or AIL regardless of whether they enter into hybrid structures. This will be a cost for taxpayers that have entered into such structures. However it will be a benefit for other taxpayers, as it will ensure that taxpayers who have entered into such structures cannot obtain a competitive advantage over domestic firms and more compliant multinationals. Accordingly the proposed approach will improve economic efficiency. | No monetary value |

| Regulators | With the proposed law change, Inland Revenue will not need to consider whether the general anti-avoidance rule in section BG 1 applies to any of the arrangements (other than taxpayers not subject to the retrospective application of the rule). It can be difficult and resource intensive to consider the application of section BG 1. Accordingly the proposed approach will save Inland Revenue administrative costs, and potentially court costs. However these are impossible to quantify at this stage. | Too difficult to quantify |

| Wider government | The Government will be able to collect NRWT or AIL from all deductible cross border interest payments, in accordance with the policy intent. This will potentially save the Government up to $60m in one off costs for past years (in respect of refunds for previously paid NRWT or AIL), and 16m per annum for future years. | A potential $60m one off benefit. A potential $16m benefit per annum going forward. |

| Other parties | Not applicable | Not applicable |

| Total Monetised Benefit | The total monetised benefit for the Government mirrors the total monetised cost for taxpayers. | A $60m one off potential benefit for the Government, plus a potential $16m per annum benefit for the Government going forward. |

| Non-monetised benefits | Administrative savings, as the Government will not have to consider the application of section BG 1 to most arrangements. Economic efficiency benefits from an equal application of NRWT to all cross border interest payments. |

Medium |

4.2 What other impacts is this approach likely to have?

The proposed approach involves the third explicit override of New Zealand’s DTAs in recent years. Accordingly, it may arouse concern that New Zealand does not respect its DTAs.

However, the proposed approach confirms the interpretive approach previously adopted by NZ, and currently adopted by some of our DTA partners and mirrors a rule already in place in Australia. It also closes a clear loophole if Inland Revenue were to change its legal interpretation. Accordingly, we do not expect disagreement over the policy outcome.

SECTION 5: STAKEHOLDER VIEWS

5.1 What do stakeholders think about the problem and the proposed solution?

Because this problem poses a base-maintenance risk, Inland Revenue and Treasury officials have not consulted with the private sector. This means that the problem identification and options have been generated by officials based on the information available. It is recognised that private sector input is an important part of the generic tax policy process.

In saying this, it is not unusual for base-maintenance changes to be made without consultation because there is a risk that publicising the existence of a perceived loophole may incentivise taxpayers to take advantage of its existence in the short term. In addition, the measure only legislatively confirms the tax treatment Inland Revenue has been applying to date. It also closes what would be a clear loophole if Inland Revenue were to change that tax treatment. Further, there will be an opportunity for the public to submit on the measure during the Select Committee process and feedback will be considered at that point.

There may be some private sector concern about the amendment, given that it applies retrospectively and will be the third explicit override of our DTAs in recent years. However, we do not expect disagreement over the policy outcome.

SECTION 6: IMPLEMENTATION AND OPERATION

6.1 How will the new arrangements be given effect?

The proposed solution will be given effect by inclusion in the Taxation (Neutralising Base Erosion and Profit Shifting) Bill 2017, which is scheduled to be introduced into the House in December 2017.

Inland Revenue will be responsible for ongoing operation and enforcement of the new arrangements. We do not have any concern about our ability to do so.

The new arrangements will have retrospective effect, except for taxpayers that have, prior to introduction of the Bill, taken the position that NRWT or AIL is not payable. We consider that this allows sufficient preparation time for regulated parties, as:

- the proposed approach will only affect a small number of taxpayers that have disputed Inland Revenue’s current legal interpretation and not settled the dispute;

- the taxpayers that have maintained their position that NRWT or AIL is not payable are aware that Inland Revenue historically does not agree, and so are on notice that their current practice may not be acceptable;

- many of those currently take the view that NRWT or AIL is payable, and so they will not need to change their current practice.

We will mitigate implementation risks by publicising the proposed approach as part of the Commentary on the Bill. We will also inform the taxpayers who currently take the view that no NRWT or AIL is payable of the proposed law change.

SECTION 7: MONITORING, EVALUATION AND REVIEW

7.1 How will the impact of the new arrangements be monitored?

The new arrangements will be monitored through Inland Revenue’s normal risk review and audit function. This will check whether taxpayers are complying with the proposed approach.

If any follow-up legislative action is required it will go through the Generic Tax Policy Process (GTPP).

7.2 When and how will the new arrangements be reviewed?

The proposed approach simply closes a potential loophole and confirms the Government’s intended tax treatment for cross border interest payments. Accordingly, we consider that no specific review of the arrangements is necessary.

Stakeholders will have the opportunity to raise concerns during the Select Committee process.

The GTPP is a multi-stage policy process that has been used to design tax policy (and subsequently social policy administered by Inland Revenue) in New Zealand since 1995. The final step in the process is the implementation and review stage, which involves post-implementation review of legislation and the identification of remedial issues. In practice, any changes identified as necessary following enactment would be added to the tax policy work programme, and proposals would go through the GTPP.