Chapter 3 - Permanent establishment avoidance

3.1 This chapter sets out a proposed rule to prevent multinationals avoiding a PE in New Zealand. The rule broadly applies where a related entity (such as a wholly-owned subsidiary) carries out sales activities for the non-resident in New Zealand under an arrangement which is contrary to the purpose of the PE provisions.

3.2 The proposed rule is an anti-avoidance measure. It is intended to apply where the non-resident’s economic activities in New Zealand should result in a PE here, but the non-resident has been able to structure its legal arrangements to avoid one arising. The proposed rule is not trying to widen the accepted international definition of a PE in substance. In particular, the rule will not apply where no material economic activities (other than the sale of the goods or services into New Zealand) are carried on in New Zealand by or on behalf of the non-resident.

3.3 The proposed rule is very similar to the ones found in the UK DPT and the Australian multinational anti-avoidance law (MAAL).

Background

3.4 A long established and widely used concept in tax systems around the world is the concept of permanent establishment or “PE”. Historically, taxing rights were based around a taxpayer’s PE in a jurisdiction. Where no PE exists, then there are generally no rights to tax business profits. The advent of the internet has made cross-border commercial traffic much easier, with no need for a company to have a PE in a country.

3.5 Under New Zealand’s DTAs, New Zealand is generally prevented from taxing a non-resident’s business income unless the non-resident has a PE in New Zealand. This is the case even if that income has a source in New Zealand under our domestic legislation.

3.6 The current definition of a PE varies from DTA to DTA, however a non-resident will generally have a PE in New Zealand if (amongst other things) either:

- the non-resident has a fixed physical place in New Zealand through which it carries on its business (excluding any preparatory or auxiliary activities); or

- there is a person in New Zealand (other than an independent agent) who has, and habitually exercises, an authority to conclude contracts on behalf of the non-resident. The person in New Zealand is still treated as concluding the contract if they negotiate all the aspects of the contract and the non-resident only formally executes the contract offshore. This is referred to as a “dependent agent PE”.

3.7 If a DTA applies, the non-resident must also have a PE in New Zealand for us to charge NRWT on certain payments by the non-resident (such as a royalty) to other parties in connection with the New Zealand sales income.

3.8 Even if a PE exists, not all of the non-resident’s sales income will be taxable in New Zealand. Instead the sales income must be apportioned between the PE and the non-resident’s offshore operations, based on the contributions of each to the sales income. For example, if goods are manufactured offshore and only sold through a PE in New Zealand, then some of the sales income will need to be apportioned offshore to reflect the profit attributable to the manufacturing activity.

The problem

3.9 Some multinationals are able to structure their affairs so they do not have a PE in New Zealand, despite having significant economic activity carried on for them here. This usually involves the non-resident establishing a New Zealand subsidiary to carry out local sales related activities. The subsidiary operates out of the kind of fixed base that meets the definition of a PE. However because that fixed base is used by a separate legal entity to the non-resident (even though they are part of the same wholly owned group), the fixed base does not give rise to PE for the non-resident. This is despite the fact that the fixed base is used by the subsidiary to affect the non-resident parent’s sales into New Zealand.

3.10 This kind of structure thus allows a multinational to avoid having a PE in New Zealand (arguably) by splitting its sales activities between wholly owned group members (or other associated entities). While these group members are treated as separate entities for legal purposes, they are part of the same economic entity in substance. Accordingly the avoidance of a PE in these circumstances is contrary to the economic substance of the arrangement.

3.11 The same concerns also arise where the non-resident’s sales activities are carried out by a New Zealand entity that is not owned by the non-resident, but is commercially dependant on it. In this case, the non-resident is also able to have sales activities carried out by a special purpose entity over which it has significant de-facto control (by virtue of its commercial dependency). The commercially dependant entity is thus also effectively an agent of the non-resident, and so its activities should be also imputed to the non-resident for the purpose of determining whether a PE exists.

3.12 An example of this kind of PE avoidance structure is set out in the appendix (structure 3), together with a more detailed discussion of the current legal issues.

3.13 Inland Revenue is also aware of cases where the multinational argues that the related party only carries out general support activities (such as marketing), but in reality they substantially negotiate the sales agreements. In such cases the related party should constitute a dependant agent PE of the non-resident. However these cases are very resource intensive to prosecute in practice, especially obtaining the requisite evidence to demonstrate the true extent of the related party’s activities.

The overseas response

3.14 The OECD is concerned about the use of DTAs to facilitate BEPS. The OECD has prepared a multilateral instrument, which will make a number of amendments to the DTAs of participating countries to counter DTA related BEPS activities (Multilateral Instrument). In particular, the Multilateral Instrument contains a widened PE definition to counter the avoidance of PE status.

3.15 This widened definition should be effective in addressing some of the PE avoidance we see in New Zealand. However an issue with the widened definition is that it will only be included in a DTA if both parties so elect. Several of New Zealand’s trading partners are not expected to elect to include the widened PE definition, including some countries from which significant investment into New Zealand is made. Therefore, the Government expects that the OECD’s PE amendments will not be sufficient to address the issue of PE avoidance in New Zealand.

3.16 The UK and Australia have adopted specific rules to address PE avoidance in their DPT and MAAL. The Australian and UK rules are very similar, and broadly apply where:

- a non-resident supplies goods or services to local customers;[6]

- a related local entity undertakes activities in relation to the sales;

- some or all of the sales income is not attributed to a local PE of the non-resident; and

- the arrangement is designed to avoid tax.

3.17 Where the rules apply, the non-resident’s supplies are deemed to be made through a local PE. The usual transfer pricing and profit attribution principles then apply to determine the amount of profits from those supplies which can be taxed in the local jurisdiction. Accordingly not all the profits from the non-resident’s local sales will be taxed when a PE is deemed to exist under the UK and Australian rules. The UK and Australian rules override their DTAs.

The proposed solution for New Zealand

3.18 The Government proposes adopting a similar rule to that in the UK DPT and the Australian MAAL. The rule would widen the circumstances in which the activities in New Zealand of a related party would give rise to a PE for the non-resident under any applicable DTA.

Application of the rule

3.19 The proposal would only apply to a non-resident that is part of a multinational group with more than EUR €750m consolidated global turnover. The EUR €750m threshold has been chosen to align application of the proposed rule with the OECD’s threshold for requiring large multinationals to file country-by-country reports. The threshold also broadly matches the AU$1b threshold adopted by Australia for its PE avoidance rule (the MAAL).

3.20 The proposed rule would apply to income years beginning on or after the date that the relevant legislation is enacted.

3.21 Under the proposed rule, a non-resident will be deemed to have a PE in New Zealand for the purposes of any applicable DTA if there is an arrangement under which:

- a non-resident supplies goods or services to a person in New Zealand;

- a related entity (either associated or commercially dependant) carries out an activity in New Zealand in connection with that particular sale for the purpose of bringing it about;

- some or all of the sales income is not attributed to a New Zealand PE of the non-resident; and

- the arrangement defeats the purpose of the DTA’s PE provisions.

3.22 It is intended that only activities designed to bring about a particular sale should potentially result in a deemed PE. Therefore general auxiliary or preparatory activities (such as advertising and marketing) would not be sufficient to trigger a possible PE under the rule. This is consistent with the definition of a PE in most DTAs, which prevent the carrying out of auxiliary and preparatory activities from giving rise to a PE. It also reflects the intended scope of the rule, which is to determine whether a particular sale is made through a PE by imputing the related party’s activities in relation to that sale to the non-resident.

3.23 Any sales-related activity carried on by an unrelated independent agent will also generally not give rise to a PE under the proposed rule (to reflect the current definition of a PE in New Zealand’s DTAs).

3.24 For the proposed rule to apply, the arrangement under which the non-resident makes its supplies into New Zealand must defeat the purpose of the PE provisions in the applicable DTA. This test is focussed on whether the non-resident’s supplies are made through a PE in substance. In determining whether this test is met, the following factors will be relevant:

- the commercial and economic reality of the arrangement;

- the relationship between the non-resident and the related entity in New Zealand;

- the nature of the services carried out by the related entity;

- whether the non-resident would have a PE in New Zealand if it and the related entity were treated as a single company; and

- whether the arrangement has any of the indicators of PE avoidance, such as the involvement of a low tax jurisdiction, specialised services, or a related entity which is allocated a low amount of profit on the basis it is carrying out low value activities while having a number of well paid employees.

3.25 The legislation enacting the proposed rule (if it is adopted) may specify some of these features.

3.26 This test should also ensure that the rule will only deem a PE to exist if the non-resident would have had a PE but for its arrangement with the related party. In this regard, the rule is intended to prevent the avoidance of a PE. It is not intended to deem a PE to exist where one does not in substance.

Example

A non-resident located in a low-tax jurisdiction sells computer equipment to New Zealand customers. The non-resident does not itself have a presence in New Zealand. However the non-resident has a wholly owned subsidiary which undertakes significant sales activity in New Zealand for the non-resident from a fixed place of business in New Zealand. The subsidiary locates customers, promotes the non-resident’s products to them, discusses their needs and tailors equipment packages for them. It also indicates likely pricing and delivery dates as well as other key terms. These terms are subject to the non-resident’s approval, although in practice approval is rarely withheld. The actual contract however is signed overseas by the non-resident, and includes some material terms that were not discussed by the subsidiary.

Under the current rules, the non-resident arguably would not have a PE in New Zealand, as it does not have a presence in New Zealand and the subsidiary did not execute the contract or negotiate all of its material terms in New Zealand. Under the proposed rule however, the non-resident would have a PE in New Zealand for the following reasons:

- The non-resident supplies goods or services to a customer in New Zealand.

- The subsidiary (who is a related entity of the non-resident) carries out an activity in New Zealand in connection with that particular sale for the purpose of bringing it about.

- Some or all of the non-resident’s sales income is not derived through a New Zealand PE of the non-resident.

- The arrangement defeats the purpose of the PE provisions in the applicable DTA. This is because the subsidiary is in substance an agent or instrument of the non-resident and carries out the non-resident’s business in New Zealand (although it is not legally an agent). In this regard:

- the subsidiary carries out nearly all of the important sales activity in New Zealand through a fixed place of business, with the non-resident only approving its activities and signing the relevant contract (to ensure no dependant agent PE arises under the DTA);

- the non-resident would have a PE in New Zealand if it and the subsidiary were treated as a single entity; and

- the non-resident’s location in a low tax jurisdiction is a strong indication of PE avoidance.

Therefore while the arrangement also has a significant commercial purpose of selling goods into New Zealand, the way the arrangement was implemented defeats the purpose of the PE provisions by preventing a PE from arising at law when one exists in substance.

Arrangements involving third party channel providers

3.27 The proposed rule is also intended to apply where an independent third party is interposed between the non-resident and the New Zealand customer as part of the arrangement. Accordingly the rule will also apply where:

- a non-resident supplies goods or services in New Zealand;

- under an arrangement in which those goods or services are to be on-sold to customers in New Zealand by a third party (whether related or not);

- a related entity to the non-resident carries out an activity in New Zealand in relation to the sale by the third party to the customers for the purpose of bringing that sale about;

- the sales are not otherwise treated as being made through a PE of the non-resident in New Zealand; and

- the arrangement defeats the purpose of the PE provisions.

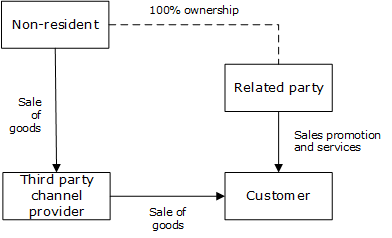

3.28 This addresses current third party channel provider arrangements, where the sale by the non-resident to the third party is part of a single arrangement in which those same goods or services are to be on-sold by the third party to a particular customer and the non-resident’s subsidiary deals with the end-customers to bring the particular sale about. See the following diagram illustrating this kind of arrangement.

(Click on the image for a full-size version | SVG source)

3.29 There can be good commercial reasons for third party channel provider arrangements, and the Government does not want to penalise them or prevent them from occurring. However they should also give rise to a PE for the non-resident in respect of its sale to the third party. This is because, under such an arrangement, the non-resident and the third party are working together to sell the particular goods or services to the end customer. Further, the non-resident’s sale to the third party is wholly dependent on the customer agreeing to purchase the goods. This means that the related party’s activities are made in relation to the non-resident’s sale to the third party as well as the third party’s on-sale to the end customer (which makes sense given that the related party acts for the non-resident, not the third party). Therefore the activities of the related party should be attributed to the non-resident for the purpose of determining whether it has a PE in respect of its New Zealand sales.

3.30 This additional rule will only apply in respect of the non-resident that makes the relevant sale into New Zealand. Therefore it will not apply in respect of any sales wholly outside New Zealand.

3.31 The rule also will not apply to a standard distributor type arrangement, under which the third party purchases goods from the non-resident and independently sells them to customers in New Zealand. This is because, in such a case, the third party would be carrying out all the particular sales activities (rather than the related party). This would be the case even if the related entity undertook general marketing and advertising activities in New Zealand in respect of the products (or after sale support).

Consequences of application

3.32 If the rule applies, then a PE is deemed to exist and the non-resident’s supplies in New Zealand are treated as being made through that PE.

3.33 Only the non-resident’s supplies that are within the ambit of the rule would be treated as made through the deemed PE. For example if the non-resident made some supplies in New Zealand in respect of which a related entity in New Zealand carried out sales activities (and the other requirements of the rule were met), then those supplies would be treated as made through a deemed PE. However if the non-resident also made other supplies in New Zealand and no related entity in New Zealand carried out any sales related activities in respect of those supplies, then those other supplies would not be treated as being made through the deemed PE.

3.34 The PE will be treated as existing for the purpose of any DTA. So the non-resident will not be able to argue the PE article of an applicable DTA prevents New Zealand from taxing the supplies where the proposed rule applies. This matches the position under the Australian MAAL and the UK DPT.

3.35 However the other provisions of a DTA in relation to the taxation of profits of a PE will still apply. Therefore if the rule applies, New Zealand will only tax the portion of the sales income that is attributable to the deemed PE. This will be determined by the application of the normal profit attribution principles.

3.36 We expect that the application of these principles will result in a fairly significant amount of the sales income being attributable to the deemed PE in most cases. We also expect a material amount of net taxable profit to remain in the PE after the deduction of related expenses. In this regard, we note that New Zealand, like many countries, has not adopted the OECD’s revised methodology for attributing profits to a PE.[7] The OECD’s revised methodology is also not currently reflected in many DTAs. New Zealand instead applies the earlier version of the OECD’s methodology.

3.37 If the proposed rule applies, then the PE will be treated as existing for the purpose of all the provisions in the DTA. So for example where the rule applies, New Zealand would be able to impose withholding tax on any royalty paid by the non-resident in respect of the supplies made through the PE (for example, in the New Zealand/Australia context, under article 12(5) of the NZ Australian DTA).

3.38 The current 100% penalty for taking an abusive tax position (under section 141D of the Tax Administration Act 1994) will also apply for the purposes of the proposed PE avoidance rule.

3.39 We note that the ultimate objective of the proposed rule is to discourage non-residents from entering into PE avoidance structures in the first place. This reflects the current policy emphasis on voluntary compliance within the Tax Acts.

Interaction with New Zealand’s double tax agreements

3.40 The proposed rule should not conflict with New Zealand’s DTAs in the vast majority of cases.

3.41 New Zealand’s DTAs are based on the OECD’s Model Tax Convention. The OECD’s Commentary to the Model Tax Convention (the Commentary) is an important part of the context in which these DTAs are internationally understood.

3.42 The proposed rule is an anti-avoidance provision. It will only apply to an arrangement which defeats the purpose of the DTA’s PE provisions. The Commentary states that, as a general rule, there will be no conflict between such anti-avoidance provisions and the provisions of a DTA. It also confirms that jurisdictions are not obliged to grant the benefits of a DTA if the DTA has been abused (noting that this should not be lightly assumed).

3.43 The OECD’s 2015 report on BEPS Action 6 (Preventing the Granting of Treaty Benefits in Inappropriate Circumstances”), which will update the Commentary in light of the OECD’s BEPS project, has also confirmed this position.

3.44 The proposed rule is also consistent with the OECD’s recommended measures to prevent the artificial avoidance of PE status, set out in its report on Action 7. In particular, the OECD recommends a measure to widen the circumstances in which the sales activities of a related party can give rise to a PE for the non-resident. This new measure will be incorporated into a DTA where both parties agree pursuant to the Multilateral Instrument, which will amend the DTAs of participating countries to implement a number of the OECD’s DTA related BEPS measures.

3.45 We propose providing that our PE avoidance rule would apply notwithstanding anything in a DTA. This is to simplify the application of the rule. Otherwise it would be necessary to show that the application of the rule was consistent with a DTA in each particular case. This would be a time-consuming and resource intensive exercise. The Government also considers that taxpayers should not be able to rely on DTAs to protect their tax avoidance arrangements. This is the same position as the UK and Australia have taken in respect of their PE avoidance rules.

6 The customer must be unrelated to the supplier for Australia’s MAAL to apply.

7 One reason for this is that the OECD’s latest approach, referred to as the Authorised OECD Approach or AOA, allows a deduction to be taken by the PE for a notional royalty paid to the head office, but does not allow withholding tax to be charged on that notional royalty (unlike a real royalty).