Chapter 2 - Background

2.1 “Feasibility expenditure” is not a defined term in tax legislation, nor is it a term of art.

2.2 Inland Revenue’s revised interpretation statement on feasibility expenditure (Interpretation Statement 17/01: Deductibility of feasibility expenditure) describes the term as “generally used to describe expenditure incurred by a taxpayer for determining the practicability of a new proposal”. This discussion document proceeds on the basis of that description.

2.3 The Supreme Court considered the deductibility of this type of expenditure in Trustpower Limited v Commissioner of Inland Revenue.[3] The legal test in the Trustpower decision is more restrictive than Inland Revenue’s original Interpretation Statement 08/02.[4] The revised interpretation statement reflects the Trustpower decision.

2.4 The original interpretation statement allowed a relatively wide scope for “preliminary” expenditure to be immediately deductible where there was no definitive commitment to proceeding with a project. The revised interpretation statement has moved away from that formulation, and interprets the test in the Trustpower decision as providing that expenditure may be deductible where it is of a type incurred on a recurrent basis as a normal incident of the taxpayer’s business, and is so preliminary as not to be directed towards materially advancing a specific project (or capital asset or enduring benefit). That is in contrast with expenditure that is aimed at making tangible progress on a capital project, to which the capital limitation would apply.[5]

2.5 The Trustpower decision and the revised interpretation statement allow less expenditure to be immediately deductible for tax purposes than previously. This is because material advancement or tangible progress is likely to occur earlier than the prior interpretation of “definitive commitment”.

2.6 Depending on whether the project is implemented or abandoned, the expenditure may also not receive depreciation deductions over time. Non-deductibility of capitalised costs will be appropriate provided the expenditure created (or was intended to create) an asset that was not expected to decline in value.

2.7 But where taxpayers would have received depreciation deductions had the project gone ahead (because the asset was expected to decline in value), but did not because the project was abandoned before it met the definition of depreciable property, this expenditure is referred to as “black hole” expenditure.

2.8 The tax treatment of black hole expenditure is a policy concern that undermines economic efficiency, as explained in the next section. The Government has already resolved many types of black hole expenditure under its incremental approach over the last few years. That includes expenditure on:

- research and development;

- resource consents;

- software projects;

- patents; and

- plant variety rights.

2.9 This area of law is relatively complicated, and the Government believes that compliance and administration costs could be reduced by simplifying it. The proposals discussed here address the black hole problem and aim to simplify the law by following accounting treatment where a taxpayer has “feasibility expenditure”.

The “black hole” problem

2.10 Black hole expenditure is business expenditure that is expected to result in an economic cost to a taxpayer, but is neither immediately deductible for tax purposes, nor deductible over time. It is not deductible over time because it does not form part of the cost of depreciable property for tax purposes.

2.11 Capital expenditure on assets that are not expected to decline in value (for example, land) is not black hole expenditure, despite the fact that it is not deductible immediately or over time. This is because the taxpayer does not expect to experience an economic loss when it purchases an asset that does not decline in value.

2.12 While assets that are not expected to decline in value sometimes do, it would only be appropriate to provide deductions for this expenditure if we taxed gains in asset values if they appreciated. Further, the tax system is economically neutral when it denies deductions for unexpected capital losses, provided that it also leaves untaxed unexpected capital gains, as New Zealand’s tax system does.

2.13 For a project that potentially involves black hole expenditure, the economic result is that the expected pre-tax rate of return of an investment that may result in some black hole expenditure must be higher than the expected pre-tax rate of return for a project that does not include such expenditure. Another way it can reduce economic efficiency is that businesses may be incentivised to complete projects that do not make economic sense, to avoid black hole treatment for sunk capital expenditure (as after completion, a depreciable asset will have been created). In either situation, the tax system has introduced an investment distortion that lowers economic efficiency.

2.14 In the context of feasibility expenditure, there will be black hole expenditure where there is feasibility expenditure at or beyond the “material advancement” or “tangible progress” stage (see the revised interpretation statement), if the project is subsequently abandoned, and if the feasibility expenditure was directed at a project or asset that was expected to decline in value. If expenditure was before that stage, it may be immediately deductible. If the project was completed and the expenditure capitalised to the asset, there would be depreciation deductions provided that the asset was depreciable property that was expected to decline in value.

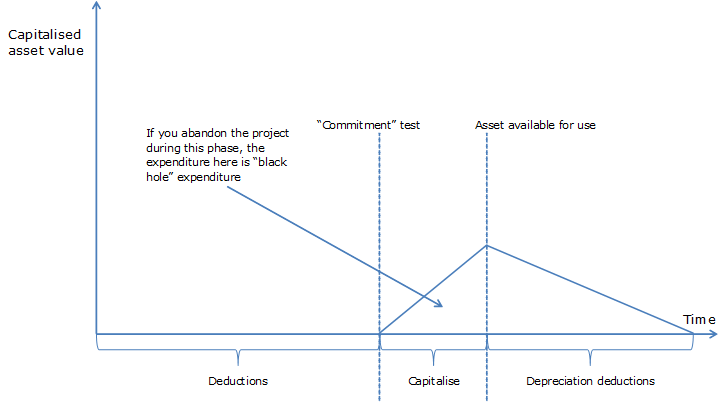

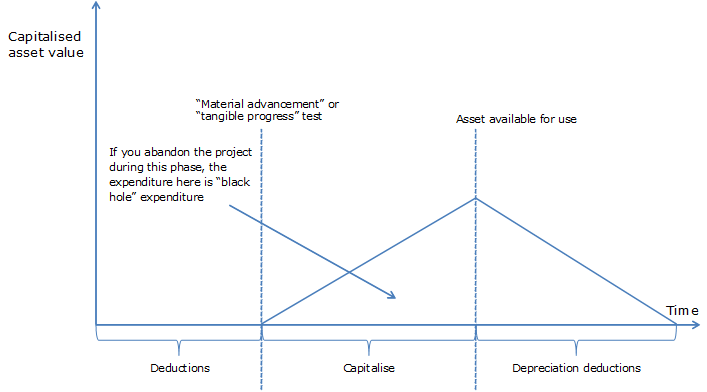

2.15 The following diagrams illustrate, in a simplified project timeline, when black hole expenditure arises in the context of feasibility expenditure under the older “commitment” test, and the newer formulation that refers to “material advancement” or “tangible progress”. The length of time during which expenditure is subject to black hole risk is greater under the “material advancement” or “tangible progress” formulation.

Figure 1: Feasibility expenditure in a project timeline – “commitment” test

Figure 2: Feasibility expenditure in a project timeline – “material advancement or “tangible progress” formulation

3 The case itself was about resource consent costs, which the Commissioner of Inland Revenue maintained were not immediately deductible. The Supreme Court agreed with that interpretation, but made comments on other feasibility expenditure that are inconsistent with Inland Revenue’s previous position.

4 “Interpretation statement 08/02: Deductibility of feasibility expenditure”, Tax Information Bulletin, Vol 20, No 6 (July 2008).

5 The revised interpretation statement has an extensive treatment of this complex area of law and represents the Commissioner’s legal interpretation. The revised interpretation statement is available at https://www.ird.govt.nz/resources/5/9/59a7819f-ec1b-4db2-a54b-3ee1caff2e00/IS+1701.pdf