Chapter 5 – The role of tax intermediaries in the transformed administration

- Summary of proposals

- Role of intermediaries

- Types of intermediaries

- Intermediaries who fall within the scope of the proposals

- The future role of tax intermediaries

- Extension of tax agent services to PAYE and GST filers

- Expanding the coverage of section 34B

- Proposed definition of “fee” (for the purposes of a new section 34B)

- Applying for listing is proposed to be optional for those who are eligible

- Change in terminology

- Taxpayers can be linked to multiple intermediaries

- Defining who is eligible for the extension of time

- Tax intermediary linking process and taxpayer control of intermediaries’ access

- Protecting the integrity of the tax system

Summary of proposals

- Amend the statutory tax agent definition to include those who are in the business of acting on behalf of taxpayers in relation to their tax affairs for a fee or who prepare tax returns on behalf of their employer. This would extend to PAYE and GST filers.

- Clarify in the TAA the persons who are eligible for an extension of time, based on whether they prepare income tax returns for 10 or more taxpayers.

- Provide a new discretion for the Commissioner of Inland Revenue to choose not to recognise a person as a taxpayer’s nominated person if doing so would adversely affect the integrity of the tax system.

Under the Business Transformation programme, Inland Revenue’s interactions with tax intermediaries will need to be efficient and tailored, so they can positively influence compliance behaviour. Under consideration are the services that Inland Revenue will provide to these intermediaries, as well as any risks to the integrity of the modernised tax system arising from tax intermediaries’ interactions with it.

Role of intermediaries

For many taxpayers, using the services of a third party (such as a tax agent, tax advisor or bookkeeper) is less costly than dealing with their own tax obligations. This is firstly because tax laws are complex, and secondly because there are other important things which taxpayers would rather do with their time (such as attending to their businesses).

Although the Government is working towards greater tax simplification, tax laws will, by their nature, continue to be complex for taxpayers. For this reason, it is expected that tax intermediaries will continue to play a vital supporting role in the future tax administration.

Recent proposals (such as the accounting income method (AIM) and the filing of GST and PAYE information directly from business accounting and payroll software) are likely to mean that intermediaries will have a greater role in advising on setting up accounting systems for businesses and in proactively checking the accuracy and coding of transactions entered into business accounting software before the end of the period. It is therefore anticipated that for many intermediaries, their workload will shift from being focused primarily on period-end preparation towards a steadier flow throughout the year.

As discussed in Chapter 5 of Towards a new Tax Administration Act, some of the ways in which tax intermediaries assist their clients to comply with their tax obligations include:

- preparing financial statements and making year-end adjustments to calculate taxable income

- providing advice about the tax implications of certain transactions and business structures

- interpreting tax laws

- educating clients about specific areas of the law and the administrative requirements involved in setting up a business and filing returns

- advising on the nature and quality of records required to be kept

- recommending accounting systems

- preparing and filing tax returns

- ensuring that clients meet their filing and payment obligations

- interacting or corresponding with Inland Revenue on the client’s behalf.

Types of intermediaries

Because of the present legislative settings and Inland Revenue’s current operational practices concerning tax intermediaries, it is useful to distinguish between different types of tax intermediaries.[70]

The intermediaries who fall within the scope of the proposals raised in this chapter can be described as those who are engaged by taxpayers to assist them to comply with their tax obligations, and who interact with Inland Revenue (or with Inland Revenue’s systems via e-services) as a fee-earning agent of the taxpayer (or in their capacity as a fee-earning tax preparer[71]). In this context, the primary questions are therefore about who should be allowed access to Inland Revenue’s systems, and what level of access is appropriate, given the Commissioner’s responsibility to protect the integrity of the tax system.

As discussed later in this chapter, it is proposed that a “tax intermediary” will, under the legislation, mean a third party who acts on behalf of taxpayers in relation to their tax affairs in a fee-earning capacity, and who is involved in the provision or preparation of tax information to Inland Revenue. Some of these intermediaries may also pay tax to Inland Revenue on behalf of taxpayers. This includes some withholding intermediaries who are specifically contracted by employers to deduct and remit PAYE payments to Inland Revenue (such as PAYE intermediaries and payroll bureaus).

A number of other third parties in the tax system (such as employers and banks) are required by law to withhold and pay tax to Inland Revenue on behalf of other taxpayers, and provide information about the income from which the tax was withheld. These third parties do not fall within the scope of the proposals raised in this chapter. This is primarily because the taxpayer does not “engage” their bank or their employer to deal with their tax affairs. Also, banks and employers do not need to access the taxpayer’s account information in order to perform their obligations, and they generally should not need to contact Inland Revenue in relation to the tax affairs of their employees or customers (with the exception of sending PAYE and RWT information and paying the tax that they withhold).

There are some similarities between certain aspects of the roles performed by “traditional” tax intermediaries and the functions of accounting and payroll software products which software providers are currently developing in collaboration with Inland Revenue. For instance, accounting software packages will calculate tax liabilities from the data input, provided that transactions are entered accurately and are coded correctly.

At present, the Government does not consider accounting or payroll software developers to be intermediaries between taxpayers and Inland Revenue for the purpose of the proposals in this chapter. Instead, these software developers are providers of a commercial product which merely assists taxpayers in calculating their tax liabilities and in sending this information to Inland Revenue.

If there are problems or errors with returns filed through software, Inland Revenue would only contact the software provider if it was a systemic issue affecting multiple taxpayers using the same software. For individual errors, Inland Revenue would contact the taxpayer or their agent.[72]

Application programming interfaces allow software products to transmit electronic returns of information (approved for transmission by the taxpayer or their agent) to Inland Revenue’s systems. In some cases, Inland Revenue might also provide access to some information about the software provider’s customers that is needed for accurate calculation of their tax liability – for example, in the context of AIM software, Inland Revenue might confirm the taxpayer’s Residual Income Tax (RIT) from the previous year. For these reasons some consideration needs to be given to software and its providers.

For instance, it will be necessary to ensure that the software can calculate tax liabilities correctly in accordance with the current tax laws, as well as reliably transmit all of the required information to Inland Revenue. The Commissioner also needs to have confidence that a particular software product will not have an adverse impact on the integrity of the tax system.

In the future, some tax intermediary firms may branch out into software development, or approved software providers may broaden their role and offer tax intermediary services. If a software provider does this, they should be eligible for listing as described in this chapter.

Intermediaries who fall within the scope of the proposals

Since banks, employers and software providers are not considered to be tax intermediaries, this chapter focuses on tax agents who currently meet the definition in section 34B of the TAA and nominated persons who act on behalf of other taxpayers in a fee-earning capacity, such as bookkeepers.

Tax agents

Section 34B(2) of the TAA defines a tax agent as a person who:

- prepares the returns of income required to be furnished for 10 or more taxpayers; and

- is one of the following:

- a practitioner carrying on a professional public practice;

- a person carrying on a business or occupation in which returns of income are prepared; or

- the Māori Trustee.

Tax agents have a critical role in the compliance behaviour of their clients, and hence in tax collection.[73] Currently, approximately 5,900 tax agents in New Zealand act on behalf of around 2.7 million taxpayers. Around 60% of these tax agents are members of professional bodies or associations.

Tax agents also have an important role in reducing Inland Revenue’s administrative costs of acquiring income and tax information from the 2.7 million taxpayers who use an agent.

Section 34B(1) of the TAA requires Inland Revenue to compile and maintain a list of registered tax agents. People and entities who meet the section 34B definition are eligible to apply to be listed as a tax agent. The current legislation recognises the importance of tax agents in influencing compliance outcomes by providing listed tax agents with an extended period of time in which to file their clients’ income tax returns, and extending by two months the end-of-year tax due date for taxpayers linked to a tax agent. In addition, Inland Revenue provides a range of services specifically for listed tax agents.

These services include:

- a dedicated phone service for tax agents to communicate with Inland Revenue

- self-service options in myIR (and in the E-File software package) which allow tax agents to file their clients’ tax returns online and view clients’ account information.

Intermediaries who may not meet the statutory definition of a tax agent

Intermediaries who do not meet the formal section 34B definition of a tax agent must be nominated by a taxpayer to act on their behalf when dealing with Inland Revenue. This includes things like receiving their clients’ statements, refunds and correspondence from Inland Revenue. People who are specifically nominated to file returns on behalf of a taxpayer also have access to electronic filing via online services in myIR, but not through E-File.

Nominated persons commonly include bookkeepers (who typically deal with GST and PAYE returns but not income tax), payroll intermediaries and tax pooling intermediaries.

The future role of tax intermediaries

Regardless of the level of simplification and automation of the tax administration system that will occur under the Government’s Making Tax Simpler agenda (and under Inland Revenue’s Business Transformation programme), many taxpayers will still prefer to pay an intermediary rather than deal with everything related to their tax affairs. Tax intermediaries will therefore have a key role in enabling their clients to benefit from the new features of the modernised tax administration.

Tax agents currently spend a considerable amount of time checking the accuracy of their clients’ accounting records and making year-end adjustments. Even with the features of a modernised tax administration, tax intermediaries will still need to carry out these tasks, as well as continue to provide advice to clients on how to comply with their tax obligations. Hence, tax intermediaries will continue to play a vital role in compliance outcomes.

Nevertheless, as noted earlier, it is inevitable that the role of tax intermediaries will change. The tax administration changes (along with changes in business systems and processes) will allow tax intermediaries to work more in real time, and spend less time on routine processes and more time on providing other valuable services to their clients.

Improved services for tax intermediaries via digital channels

To support tax intermediaries in enabling their clients to benefit from the new features of the modernised tax administration, Inland Revenue intends to offer more online self-service options.

Towards a new Tax Administration Act invited submissions from tax agents on which current Inland Revenue services they find most useful, and what types of services they would like in the future. The submissions received showed that tax agents would like to see a wider range of self-service options so that they can work more efficiently and manage clients’ tax affairs in real-time.

Some existing services could be streamlined and made more efficient through online self-service channels, such as:

- requesting a notification to the client’s myIR portal asking the client to provide records to their tax intermediary

- changing the filing frequency or basis for GST

- requesting an amendment to an assessment for a client’s tax return

- transferring funds between accounts for tax pooling (below a certain threshold)

- accessing client filing statistics.

An intermediary will only be able to see the tax types for which the client has given authorisation for them to view and/or edit.

The examples below illustrate the benefits of using electronic self-service to issue a records request, compared with having Inland Revenue send a letter.

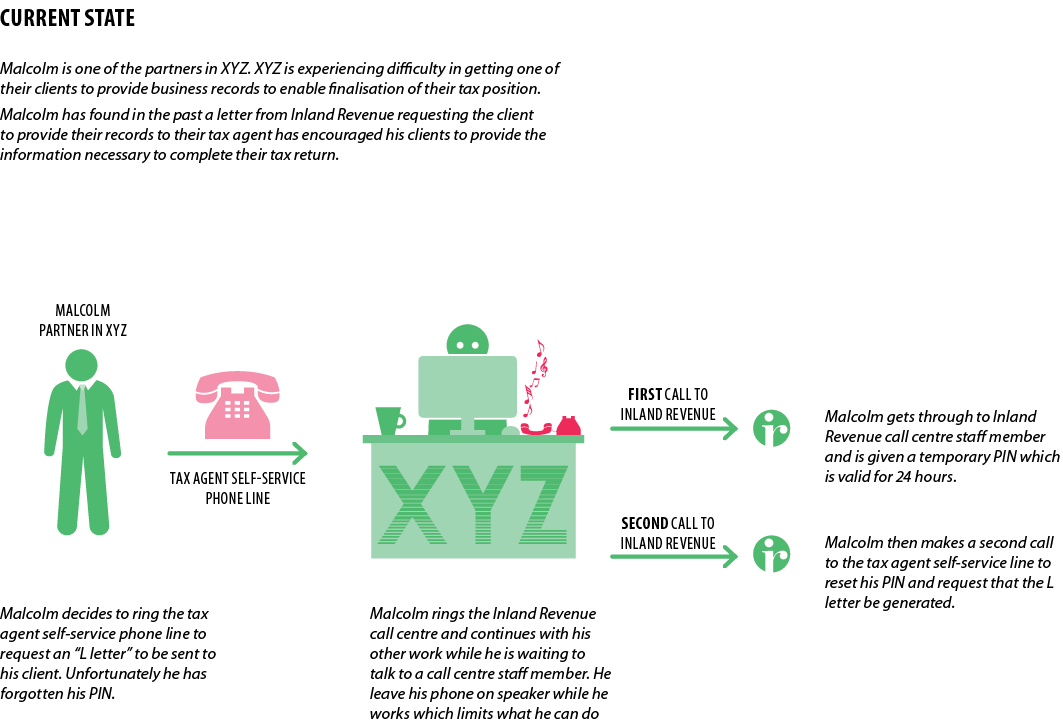

Example – issue of an “L letter”

XYZ Tax Limited (XYZ) is a Dunedin chartered accountancy firm which offers tax return preparation and advisory services. XYZ is experiencing difficulty in getting one of their clients to provide business records. Malcolm – one of the partners in XYZ – has found that, in the past, a letter from Inland Revenue requesting their records (an “L letter”) has encouraged his clients to provide the information needed to complete their tax returns. Malcolm decides to ask Inland Revenue to issue an L Letter in this instance. To do this, he has to use the tax agent self-service phone line, but he has forgotten his PIN.

He rings the Inland Revenue call centre and continues with his other work while he is waiting. He leaves his phone on speaker while he works, which limits what he can do. The Inland Revenue call centre staff member gives him a temporary PIN which is valid for 24 hours.

Malcolm then makes a second call to the tax agent self-service line to reset his PIN. Then he can follow the prompts on the self-service line to request the issue of the L letter.

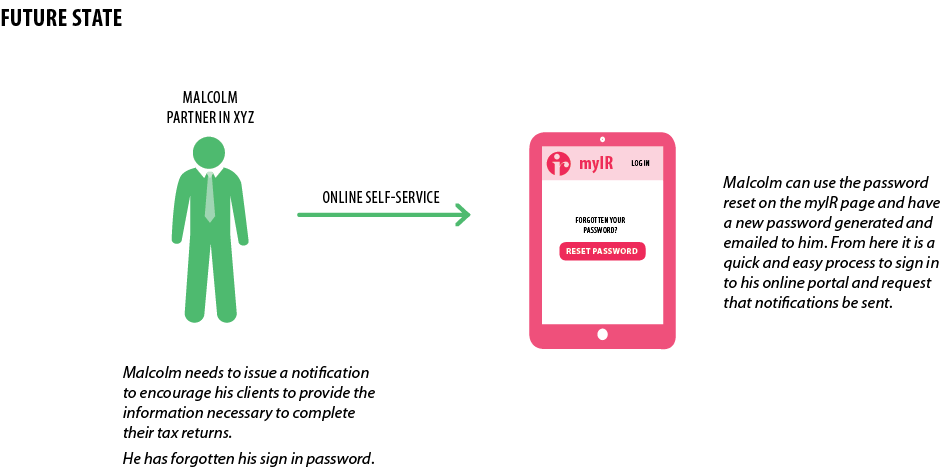

Example – issue of an electronic request to provide tax records

This process could be streamlined through the use of online self-service. Malcolm will sign in to his online portal in myIR and pull up his full client list. He can simply tick the boxes to select the clients who need a records request. The system will do the rest. If he forgets his password, he can use the password reset on the myIR log-in page and his new password will be emailed to him straight away.

Although the scenario described in the second example does not demonstrate a large technological advancement, the difference between the two examples is a good demonstration of the efficiency gains that can be made through providing more online services for tax intermediaries and moving more existing self-service options to digital channels.

The following examples use another scenario to illustrate how online self-service can make things easier for tax intermediaries.

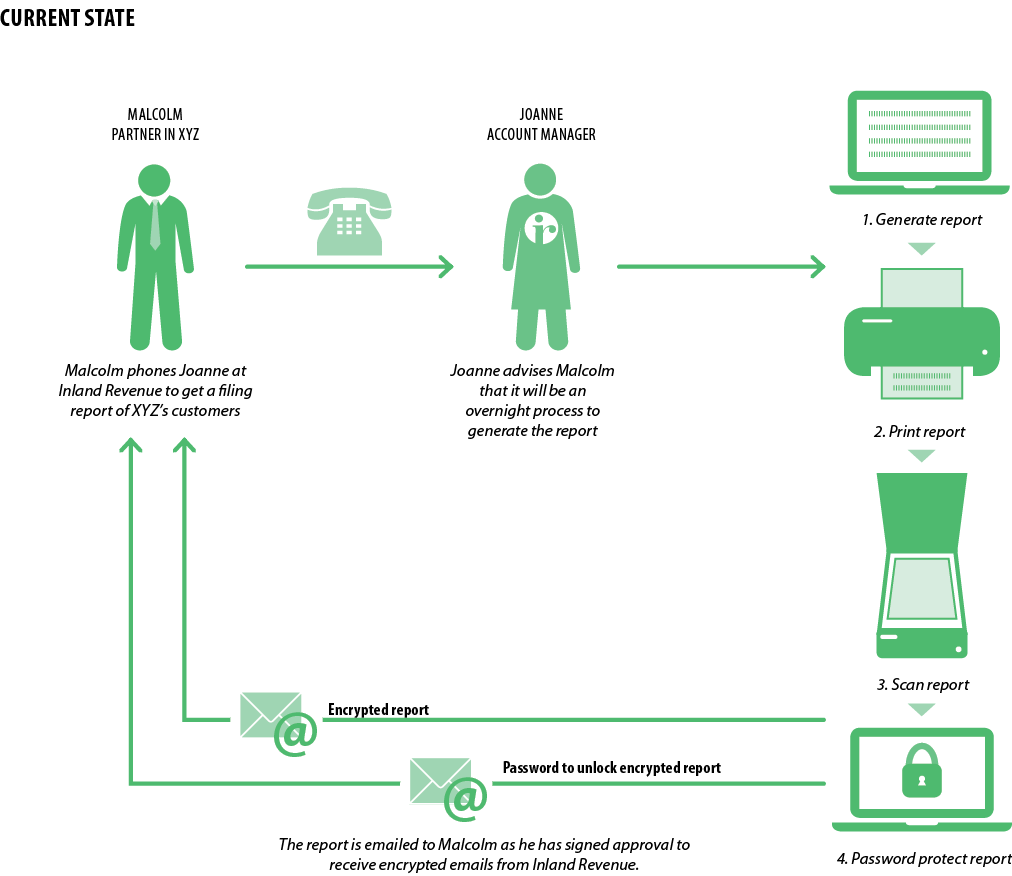

Example – requesting a report on clients’ filing performance

To identify all of XYZ’s clients that require more support to meet their filing obligations, Malcolm would like a detailed, up-to-date report of their filing performance and their unfiled tax returns for the current extension of time year. He rings Joanne, an account manager at Inland Revenue, who advises that the report will be generated overnight. Malcolm wants it as soon as possible, so he asks Joanne if it can be sent by email. Since Malcolm has previously provided signed approval to release information under Inland Revenue’s encrypted email policy, Joanne confirms that it she can email it. Joanne generates the report, prints it, scans it as a PDF, password protects it and emails it to Malcolm (with a separate email containing the password). When Malcolm receives the report the following day, he thinks how helpful it would be to have a report which covers filing information for other tax types, rather than just income tax. He also notices that the report is not completely up to date, as it does not include returns which have been filed but not yet processed.

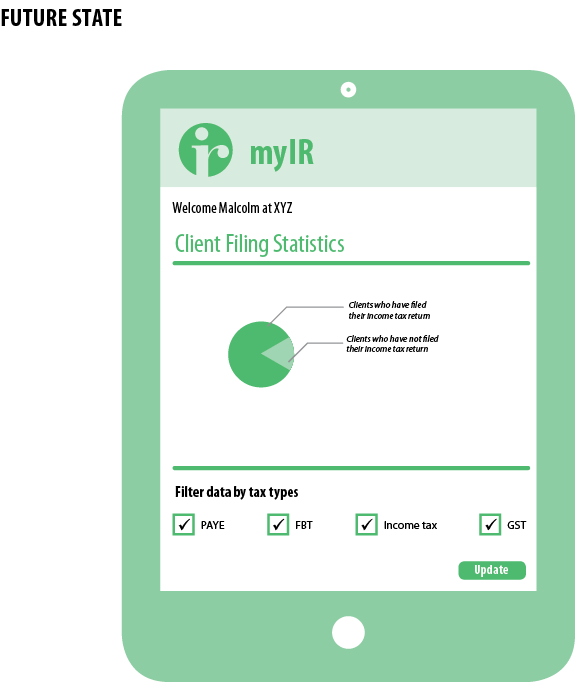

Example – self-service access to client filing statistics

This process could be streamlined through allowing intermediaries to access client filing statistics in myIR. Malcolm will simply log in to request the filing data, and can tailor it to include whatever tax type details he needs. He will be able to view up-to-date information in real-time. XYZ will be able to monitor their clients’ filing performance and provide early assistance to any clients who need it.

Extension of tax agent services to PAYE and GST filers

The tax agent definition in section 34B only covers income tax returns, so does not include intermediaries who only deal with PAYE or GST, or who prepare fewer than 10 income tax returns per year.

Intermediaries who do not meet the legal definition of a tax agent are currently not able to access Inland Revenue’s services provided to tax agents. This restriction is not required by law, but is an administrative decision by the Commissioner to better ensure the integrity of the tax system.

However, the Government understands that many stakeholders consider that there needs to be more recognition of tax intermediaries who may not act for clients with respect to income tax but who offer payroll or GST services.

It is proposed that these intermediaries (as long as they meet some minimum eligibility requirements) be able to register with Inland Revenue, so they and their clients may benefit from some of the services currently offered to tax agents.

It would be inappropriate to grant intermediaries not meeting the current section 34B definition of a tax agent more access rights without being able to deny or remove their access if the intermediary is considered to be a risk to the integrity of the tax system. By granting them similar benefits to those received by tax agents, these intermediaries would be given an elevated position of trust in the tax system. From a fairness perspective, they should therefore be subject to the same integrity standards and rules. There may be value in a statutory rule that grants the Commissioner discretion to suspend if necessary an intermediary’s status and access.

Expanding the coverage of section 34B

To deal with this issue, the tax agent definition in section 34B could be widened to cover intermediaries who act on behalf of taxpayers in relation to their tax affairs for a fee,[74] as well as those who prepare tax returns on behalf of their employer.[75]

It is proposed that bookkeepers, payroll intermediaries, tax pooling intermediaries and other intermediaries should be eligible to apply for listing.

Proposed definition of “fee” (for the purposes of a new section 34B)

To clarify the application of a new definition, it is proposed that a “fee” could be defined as consideration paid for the tax intermediary services supplied, which is (or has a monetary value equivalent to) a dollar value typically paid in an arm’s length transaction on the open market for the type of services provided. This could also include margins charged by the intermediary (for instance, a percentage of a tax refund paid out) and any government subsidies, as well as direct fees.

Applying for listing is proposed to be optional for those who are eligible

The Government recognises that in the new START system, nominated person access (as opposed to access as a listed tax agent) will likely be sufficient for some intermediaries. Applying for listing under section 34B will be optional for those who qualify. Intermediaries will only apply for listing if they would gain a benefit, for example through the additional services.[76]

Change in terminology

To better reflect the proposed wider group of tax intermediaries who would be eligible to apply for listing under section 34B, it may be appropriate to replace the term “tax agent” with an alternative term. For instance, the references to “tax agent” in the TAA (including in section 34B) could be changed to “tax intermediary”, meaning the wider group representing taxpayers for a fee, as well as those preparing tax returns for their employer.

Taxpayers can be linked to multiple intermediaries

A taxpayer might engage more than one intermediary for different tasks, so they will be able to link to multiple intermediaries in Inland Revenue’s system.

Defining who is eligible for the extension of time

The Government considers that the existing extension of time for filing and paying income tax for clients linked to tax agents should continue to apply to income tax only. Any extension of time for PAYE would be inconsistent with the policy objective of increasing the regularity at which businesses send PAYE information to Inland Revenue.

It is proposed that the legislation defines eligibility for an extension of time separately from the definition of a tax intermediary or agent. This is to ensure that the two concepts are not automatically linked.

At this stage, there are no firm proposals for any change to the eligibility criteria for an extension of time: however, as was noted in Towards a new Tax Administration Act, the extension of time may become less important in the modernised tax administration and may be reviewed later. For the time being, only listed intermediaries who prepare income tax returns for 10 or more taxpayers will be eligible.

Tax intermediary linking process and taxpayer control of intermediaries’ access

To enable easy and convenient client self-management of intermediaries’ access, Inland Revenue is expecting to make more online self-service options available to taxpayers. Appendix 2 explains the expected process for intermediary access to taxpayers’ accounts.

Protecting the integrity of the tax system

If the Commissioner of Inland Revenue believes that accepting an application to be a tax agent would adversely affect the integrity of the tax system, she must refuse the application.[77] The Commissioner may also remove a person from the list of tax agents if she is satisfied that the applicant is not eligible to be a tax agent, or if their remaining on the list would compromise the integrity of the tax system.[78]

Listing a person as a tax agent (or allowing them to stay on the list) may be determined to have an adverse effect on the integrity of the tax system if the applicant (or a “key office holder” of the applicant if the applicant is not a natural person):

- is an undischarged bankrupt

- is a liquidated company

- is a company under voluntary administration or in receivership

- is not allowed by the Registrar of Companies to be a company director

- has been notified of a breach by the disciplinary body of a professional organisation they belong to

- has been convicted of any criminal offence involving dishonesty

- has a record of non-compliance with any Inland Revenue Acts, including overdue returns or payments, or social policy that Inland Revenue administers.

The above criteria are cited in the form Application to be listed as a tax agent or update a tax agent’s details (IR791) but the Commissioner may also consider other factors to determine whether listing a person as a tax agent would adversely affect the integrity of the tax system.

Consideration has been given to whether more regulation of tax intermediaries (like in Australia, for instance) might be justified. An argument can be made that setting some minimum standards for eligibility to apply for listing as a tax agent would reduce the likelihood of an unsuitable advisor being listed. These standards could require certain qualifications, years of relevant experience or membership of an approved professional body.

Requiring membership of an approved professional body could be considered to reduce the tax integrity risk because professional accounting bodies have their own code of conduct and disciplinary procedures for members who contravene that code.

There would be a case for regulation if it can be determined that the resulting tax integrity benefit would outweigh the additional costs imposed. However, this is unlikely to be the case. Instead, the imposition of higher barriers to entry is likely to increase the price of tax intermediary services (by reducing the supply of those services) and thus increase taxpayers’ costs of getting advice. It is also likely that people who do not qualify will seek access as nominated persons, rather than as tax agents.

As well as delisting, other measures are currently used to discourage the types of behaviour by intermediaries that would adversely affect the integrity of the tax system. These include sanctions such as promoter penalties and criminal prosecutions for aiding and abetting (or directly engaging in) fraud. If taxpayers have incurred penalties due to a mistake or unscrupulous behaviour by their intermediary, they have a remedy in contract law and in general consumer law to recover their loss from the person.

Currently, the number of declined applications and delistings is relatively low. This is not expected to change.

It is therefore considered that any tax integrity benefit from stricter eligibility requirements for tax intermediaries would be outweighed by higher compliance costs for taxpayers (along with increased administrative costs for Inland Revenue), and would unfairly penalise a large proportion of currently listed tax agents. On this basis, the Government does not propose introducing any stricter eligibility rules for tax intermediaries.

Intermediaries’ access as nominated persons

The Commissioner can only revoke a nominated person’s authority to act for a taxpayer at the taxpayer’s request – even if the person has been convicted of fraud and is acting on behalf of the taxpayer for a fee. As a result, there is a risk that an individual removed from the list of tax agents for integrity reasons could come back into the system as a nominated person.

To deal with the problems caused by a small minority of nominated persons, the Government proposes that the Commissioner be granted the discretion to refuse to accept a nominated person application if that person has been delisted for tax integrity reasons, or if allowing that person access would adversely affect the integrity of the tax system.

The criteria that the Commissioner might apply in exercising this discretion could be the same criteria used to remove a person from the list of tax agents. Hence, the Government does not intend to introduce a prescriptive set of criteria into the legislation.

The discretion to refuse to accept a nominated person application is proposed to be limited to situations where the person is acting on behalf of a taxpayer for a fee or otherwise acting in a professional capacity. It is important that taxpayers still have the freedom to have a friend or relative of their choosing (or a volunteer in the case of a non-profit body) act on their behalf in relation to their tax affairs if they wish.

[70] These are not formal distinctions but explain the different roles of these intermediaries and the different levels of access to Inland Revenue’s services. In practice, nominated persons who act on behalf of taxpayers in a fee-earning capacity (such as bookkeepers, for instance) can be thought of as tax agents who do not meet the TAA definition of a tax agent – either because they are not in the business of preparing income tax returns, or because they prepare fewer than 10 income tax returns per year.

[71] “Acting in their capacity as a fee-earning tax preparer” would include situations where a person who acts on behalf of some taxpayers for a fee, also performs pro bono work for family or friends.

[72] If a taxpayer has trouble meeting their filing obligations or calculating tax correctly because of a software error, they would need to contact the software provider to get the problem sorted out.

[73] Erard, B. (1993). Taxation with representation: An analysis of the role of tax practitioners in tax compliance. Journal of Public Economics, 52 (2), 163-197.

[74] “Tax affairs” includes social policy administered by Inland Revenue (such as student loans and Working for Families tax credits).

[75] A change to the section 34B definition would have no impact on tax advisors’ privilege under section 20B.

[76] In the current system, nominated persons who file returns online on behalf of multiple taxpayers have a myIR log-in for each client. Because tax agents can file electronically using the Commissioner’s E-File software, they do not need to have multiple log-ins. In START, nominated persons will also have just one log-in for Inland Revenue’s e-services, regardless of how many taxpayers they are linked to.