Chapter 2 – Tax information and confidentiality

- Summary of proposals

- Introduction

- Environment

- Current legislative framework

- A new approach for tax information

- Enforcement of taxpayer confidentiality

Summary of proposals

- Narrow the coverage of the confidentiality rule to information that would identify a taxpayer.

- Retain an ability for the Commissioner to withhold certain non-taxpayer-specific information in order to protect revenue collection.

- Clearly set out the broad categories of exceptions to the new taxpayer confidentiality rule.

- Provide a legislative framework for sharing Inland Revenue information with other agencies for the provision of public services that:

- offers greater flexibility through the use of regulations to authorise sharing

- sets out a cohesive set of principles governing when sharing regulations will be appropriate

- provides greater, and more consistent, transparency regarding how Inland Revenue information is shared.

- Allow information to be shared for public services without need for regulations when the taxpayer concerned has consented.

- Retain the obligation on Inland Revenue officers to keep information confidential.

- Clarify how the confidentiality rule applies to people who receive Inland Revenue information.

- Clarify the penalty for improper disclosure.

Introduction

One of the Government’s four priorities is delivering on its Better Public Services objectives within tight fiscal constraints. To do so, agencies need to develop new business models, work more closely with others and harness new technologies to meet emerging challenges. A critical aspect of Better Public Services is improving the use of information within and across agencies. Better use of information is also central to Inland Revenue’s future direction as an intelligence-led agency.

Many Better Public Services initiatives are driven by, or are driving, better use of government data. The Government is focused on agencies achieving better outcomes for New Zealanders through wider and smarter use of data held by government.[1]

Information is critical to Inland Revenue’s ability to perform its functions. Much of that information is provided by taxpayers. This may be information about themselves (such as in an individual or business income tax return) or about other taxpayers they deal with (such as in an employer monthly schedule). Inland Revenue can enforce the provision of information that is not received through regular channels and has significant powers to do so, but the use of these powers is the exception rather than the rule.

For taxpayers to be comfortable providing their information, they need to feel the information requested is reasonable and is treated appropriately by Inland Revenue. Currently, surety is given by what is often referred to as the “tax secrecy” rule – which essentially requires that information provided to Inland Revenue is for tax purposes and will only be used for such purposes.[2] Rules about the confidentiality of tax (and taxpayer) information are common across tax agencies internationally.

“Tax secrecy”, or at least the component that relates to the confidentiality of a taxpayer’s individual affairs, is seen as a critical component of the integrity of the tax system, as reflected in the definition of integrity in section 6 of the TAA.

However, the current rules can lead to tensions – in particular tensions between:

- confidentiality and wider government objectives, including the more efficient operation of government and the provision of services that can be achieved through increased cross-government information sharing

- confidentiality and the Official Information Act principle of open access to information held by government.

Inland Revenue already shares a significant amount of information with other agencies – so this is not a new concept. Rather, the proposals in this document seek to modernise and clarify the rules to better provide for confidentiality and sharing in the future, and balance the trade-offs inherent in decisions about whether to share.

Chapter 4 of Towards a new Tax Administration Act began to explore these issues, resulting in a range of submissions. In this chapter the Government sets out its further thinking and proposals for the future tax information confidentiality and disclosure framework. Discussion on the feedback received on Towards a new Tax Administration Act is incorporated into these proposals.

Environment

The Data Futures Forum, a working group set up by Ministers[3] to consider how New Zealand can get the best value from data, has set out the rapidly changing information environment and the possible impacts and opportunities of the ever-increasing digitisation of everyday life. In its first discussion paper, the Forum focused on linking and sharing all that information and the benefits, risks and challenges that arise.[4] An example of some of the benefits is the Ministry of Social Development’s use of integrated data from various sources to better understand which services get better outcomes. This enables more efficient and effective targeting of public funds and better service provision to those in need, and is known as the “social investment approach”.[5]

Data plays a key role in the social investment approach and is a core focus of the newly established Social Investment Unit tasked with implementing this approach. The Social Investment Unit is currently establishing a data exchange, the Data Access Service, which will provide access to identified information under a federated data model, subject to the informed consent of individuals and standards that comply with all relevant legislation.

The Government is currently reviewing the Privacy Act and the Statistics Act in this context. Other agencies are also considering their information settings, including the New Zealand Customs Service, which consulted in 2015 on its legislative review, including proposals for a new information sharing framework. Cabinet has recently approved a proposed new framework for inclusion in a new Customs and Excise Bill.[6]

Previous New Zealand research has indicated that individuals think that more information is shared across government than is in fact the case.[7] Further research in 2013 found that small business owners were generally in favour of Inland Revenue sharing information about individual businesses with other government departments; however, the context was important.[8]

The Privacy Commissioner’s Privacy Concerns and Sharing Data survey for 2016 also found that public concern regarding data sharing within government has decreased from previous years.[9] Recent research carried out with businesses on behalf of Inland Revenue has come to similar conclusions for business-related information – namely that context and safeguards are important, and that there is much greater comfort with sharing for government or public good purposes, but little support for sharing if there is exclusively private benefit.[10]

Although the environment is complex and changing, in the proposals contained in this discussion document, the Government is seeking to best address the issues within the tax context, while remaining consistent with the wider government landscape. The proposals seek to future-proof the rules as far as possible, balancing flexibility against a need to ensure New Zealanders trust that the information they provide to Inland Revenue is appropriately used and protected.

Current legislative framework

For most public sector agencies the primary rules governing collection and disclosure of information are found in the Privacy Act 1993 and the Official Information Act 1982. For Inland Revenue, however, the primary rules are contained in Part 4 of the TAA.

Inland Revenue’s tax secrecy rule is set out in section 81 of the TAA. The term “tax secrecy” does not appear in the TAA, rather section 81 requires all Inland Revenue officers to “maintain, and assist in maintaining, the secrecy of all matters relating to” the Inland Revenue Acts.

The confidentiality of tax information is important for three key reasons. First, it is seen as a balance for Inland Revenue’s information-gathering powers. Revenue agencies are traditionally granted wide information-gathering powers so they can ensure that taxpayers are meeting their obligations. Second, confidentiality has also traditionally been considered necessary to promote compliance. The rationale is that taxpayers will be more comfortable providing information to Inland Revenue if they are assured it will go no further. Third, the courts have recently referred to the principle of taxpayer privacy. The right of taxpayers to have their information kept confidential is now also recognised in section 6 of the TAA in defining the integrity of the tax system.

While tax (or taxpayer) confidentiality provisions are common across the world, it is important to consider whether these key reasons still apply, or still apply in the same way in modern tax administration, particularly given the greater moves to cross-agency cooperation both domestically and internationally.

Many other New Zealand agencies have information-gathering or search powers.[11] Inland Revenue’s powers to access information are generally broader than those of other agencies. This is necessary to enable the Commissioner to ensure that taxpayers are meeting their obligations. While many other agencies have various search and seizure powers, these often require a warrant to exercise, whereas this is not the case for Inland Revenue. However, some other agencies with similar broad powers to Inland Revenue are not subject to the same strict rules of confidentiality or secrecy.

A transparency reporting trial undertaken by the Office of the Privacy Commissioner in 2015 notes that the majority of government agency information requests do not require a court order, but most are made under statutory compulsion.[12] Appendix B to the report summarises the “three tiers” of information gathering: by court order, by statutory compulsion and under the exceptions to the privacy principles set out in the Privacy Act 1993.

Another reason given for confidentiality is that it promotes voluntary compliance. Whether this is actually the case has generated some debate, particularly following revelations or allegations of fraud or tax evasion.[13] The answer, however, remains unclear.[14] In the United States, the debate over whether tax privacy promotes individual compliance has been described as “as old as the income tax itself”.[15]

A further consideration is changing public expectations. In the international, revenue-specific context, there is a significant increase in the information shared, and increasing public expectation that information is available. There also appears to be greater acceptance of information sharing domestically, provided that appropriate safeguards are in place. The Government will be continuing to explore the social licence for data sharing through the work of the Data Futures Partnership. The Partnership is engaging with New Zealanders through a participatory process to inform the development of guidelines designed to support organisations seeking to secure the trust and confidence of the people whose data they are using.

A new approach for tax information

What should be confidential

In order to administer the tax system and associated social policy products such as Working for Families, child support, student loans and KiwiSaver, Inland Revenue collects and holds information on virtually all New Zealanders, as well as most corporate and other entities, such as trusts and partnerships. This is information that taxpayers are compelled to provide to Inland Revenue, and therefore it must be treated with care.

While the Privacy Act provides a framework for the collection, use and disclosure of personal information, much of the information held by Inland Revenue is non-personal, and no equivalent legislative framework exists. Given the breadth of information Inland Revenue holds, and the sensitivity of some of this information, rules about confidentiality are still considered necessary.

A key issue with the current rules about tax information is the difference between Inland Revenue and other government agencies in relation to official information. The Official Information Act 1982, which defines “official information” as including any information held by a department, provides a presumption of availability of information – that official information will be available to requestors unless there is a good reason for it to be withheld. Reasons for withholding include protecting the privacy of natural persons and not unreasonably prejudicing commercial positions or disclosing trade secrets.

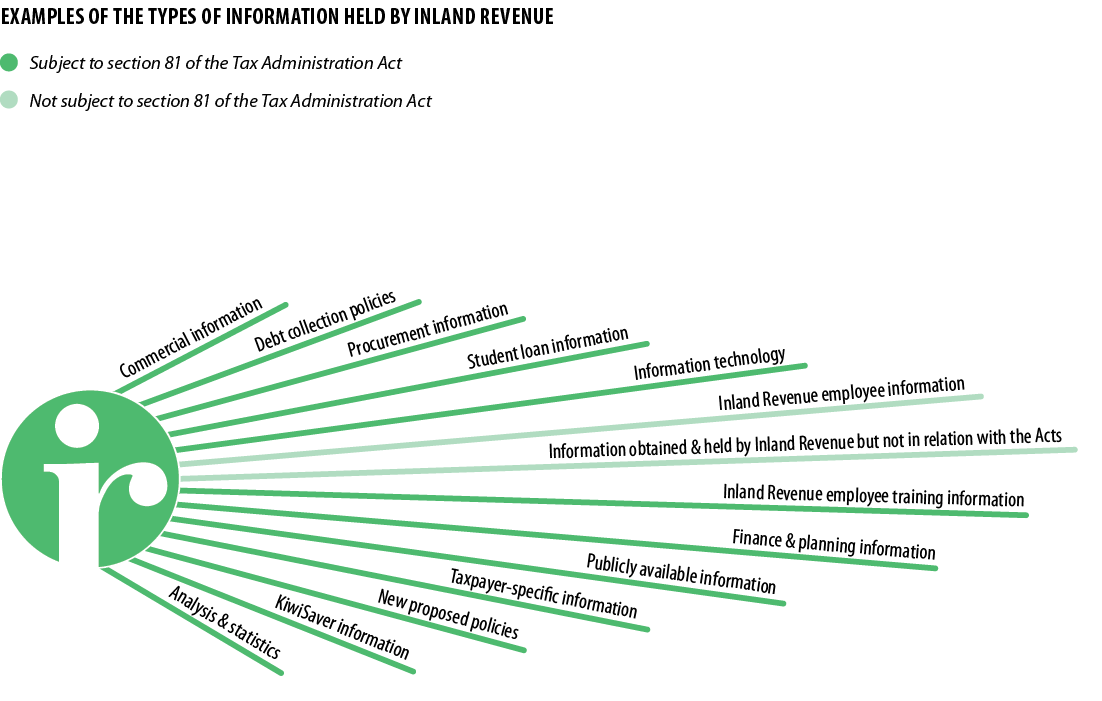

In contrast, the starting point of the rule relating to tax information is that Inland Revenue officers must maintain the secrecy of “all matters relating” to the Inland Revenue Acts. While the precise limits of this rule are not clear, it is clear that the section is not limited to information about taxpayers.

The breadth of the rule means that a wide range of information, relating to procurement, analysis and statistics, information technology, finance and planning, policy development and even publicly available information is subject to the rule in section 81 unless a subsequent exception applies. Much of this information would not be confidential in the hands of any other government agency.

In Towards a new Tax Administration Act the Government proposed narrowing the coverage of tax secrecy from all information relating to the Revenue Acts, to protecting information that identifies, or could identify a taxpayer. This is the approach taken in Australia and Canada, and a similar limitation applies in the United States where the legislation protects “return information”.

Submissions received on this proposal were mixed. Some submitters were in support, while others thought that the current broader rule should be retained due to the small size of the New Zealand economy and an associated risk that it would be too easy to identify taxpayers from aggregated information. Those submitters in support of narrowing the coverage of the rule were clear that adequate safeguards for taxpayer information were a necessary precursor. Information that might not identify a taxpayer but that was still commercially sensitive was also a significant concern for several submitters.

The key reasons cited for confidentiality of tax information have, at their core, the protection of information about the taxpayers or entities that provide information to Inland Revenue. Each of these concerns – the impact on voluntary compliance, balancing information collection powers or the protection of privacy – is focused on the harm that would result from the disclosure of taxpayer (or entity) information. There does not, therefore, appear to be a clear rationale for the breadth of the current rule, and the inconsistency this creates for Inland Revenue as compared to other agencies with respect to the Official Information Act, as well as the inconsistency with the Government’s Better Public Services objectives.

Proposal – taxpayer confidentiality

The Government therefore proposes, consistent with the direction indicated in Towards a new Tax Administration Act, to replace the current “tax secrecy” rule with a rule that Inland Revenue must keep confidential information that relates to the affairs of, or identifies (or could identify), a taxpayer. This new rule will better reflect the various policy rationales for protecting certain tax information, and continue to protect sensitive taxpayer information, while allowing the release of more generic, non-taxpayer-specific information.

The proposed approach would be similar to the Australian legislation which protects information relating to the affairs of an entity. A key concern submitters raised about the proposal was how the new rule would apply, particularly given the small size of the New Zealand population and markets, and whether it would lead to the release of information that could reasonably identify a taxpayer. The new confidentiality rule would apply not only to information that clearly identifies an entity, but also to information that could be used to identify an entity by a process of deduction. Below are both hypothetical and actual examples demonstrating the boundaries of the rule.

Example — the “haysnorkel industry”

The Australian Tax Office (ATO) collects information on the volume of production of haysnorkels in Australia. Because haysnorkel production is a very specialised industry, only three firms manufacture haysnorkels in Australia. One major producer meets the needs of most of the Australian market, and two much smaller boutique producers manufacture only a small number of haysnorkels each year. If the ATO were to disclose information on the aggregate production of haysnorkels in Australia, then it would be possible for anyone with a general knowledge of the haysnorkel market to deduce (with a fair degree of accuracy) how many haysnorkels were being manufactured by each producer. In this case, the disclosure of aggregate production information would allow a particular haysnorkel producer to be identified, despite not explicitly doing so. Such aggregate information would therefore be protected information.[16]

Example — minerals resource rent tax

Following the introduction of the minerals resource rent tax (MRRT) in Australia, information was sought from the ATO about the amount of MRRT revenue collected. The ATO refused the requests initially as information from only one quarter was available and there was considered to be a significant risk that particular taxpayers and the amounts they had paid would be identifiable without much difficulty. Following the receipt of a second quarter of revenue the information was disclosed. The decision to release the information was based on a range of factors, including:

- that the second quarter income was substantially larger than the first

- the total number of MRRT payers

- the degree of uncertainty with which such information could be used to deduce what a particular payer had paid advice from the Australian Government Solicitor.[17]

Example — sharing non-identifying data

A New Zealand NGO wants access to de-identified social sector data (from several social sector agencies and Inland Revenue) to support their service delivery. This will enable the NGO to assess which of their services are most effective and therefore better target services in the future.

The NGO does not hold individual authorisations to access identified data. It is seeking access to quarterly data that covers their customers and a comparable set of non-customers. Exact data point needs are expected to change over time.

Provided the data is aggregated or depersonalised to the extent that individuals cannot be identified, this information would no longer be subject to the confidentiality rule. Access to such data might be directly from Inland Revenue or via a centralised data platform such as the Integrated Data Infrastructure managed by Statistics New Zealand, which contains data from a range of agencies including Inland Revenue.

Development of guidance will be important to help Inland Revenue staff and taxpayers understand the new ambit of the rules. Information that identifies a taxpayer will clearly be covered by the rule. Information that does not at first glance identify a taxpayer will also remain protected, if that information could be used to identify a particular taxpayer. While in general the application of the rule will be clear, in some cases the release or withholding of information will need careful consideration.

Sensitive information that does not identify a taxpayer

Current exceptions allow various types of non-taxpayer-specific information to be released to other government departments or more widely. Some of these exceptions require the application of difficult balancing tests. In some cases this applies to information that would not generally be withheld by other government agencies – for example information for the purposes of understanding or developing policy decisions.[18] Under the Official Information Act such information would usually be released (subject to timing if the policy is still under development).

Inland Revenue does hold very sensitive information besides that relating to specific taxpayers, and the release of this could damage the integrity of the tax system. This would include information regarding audit or investigative techniques or strategies, compliance information, thresholds, analytical approaches and so on. The release of such information could affect the Crown’s ability to collect revenue, for example by enabling taxpayers to “game” or defraud the system.

The Official Information Act allows information to be withheld if the release would prejudice the maintenance of the law, but there is no specific provision allowing information to be withheld if it is required to protect the public revenue.[19] In contrast, the Australian Freedom of Information Act 1982 contains a number of protections that are used as grounds by the Australian Tax Office to withhold sensitive information that might, if released, damage the tax system or affect revenue collection.[20] United Kingdom freedom of information legislation also contains a broader protection for non-taxpayer-specific, sensitive revenue information.[21]

While Inland Revenue’s sensitive information may be covered by the “maintenance of the law” exception from disclosure in the Official Information Act, that may not always be the case. The protection of public revenue is considered of sufficient importance that a residual protection should be retained in the TAA. This will allow the Commissioner to withhold such information if it is considered likely to affect the integrity of the tax system.

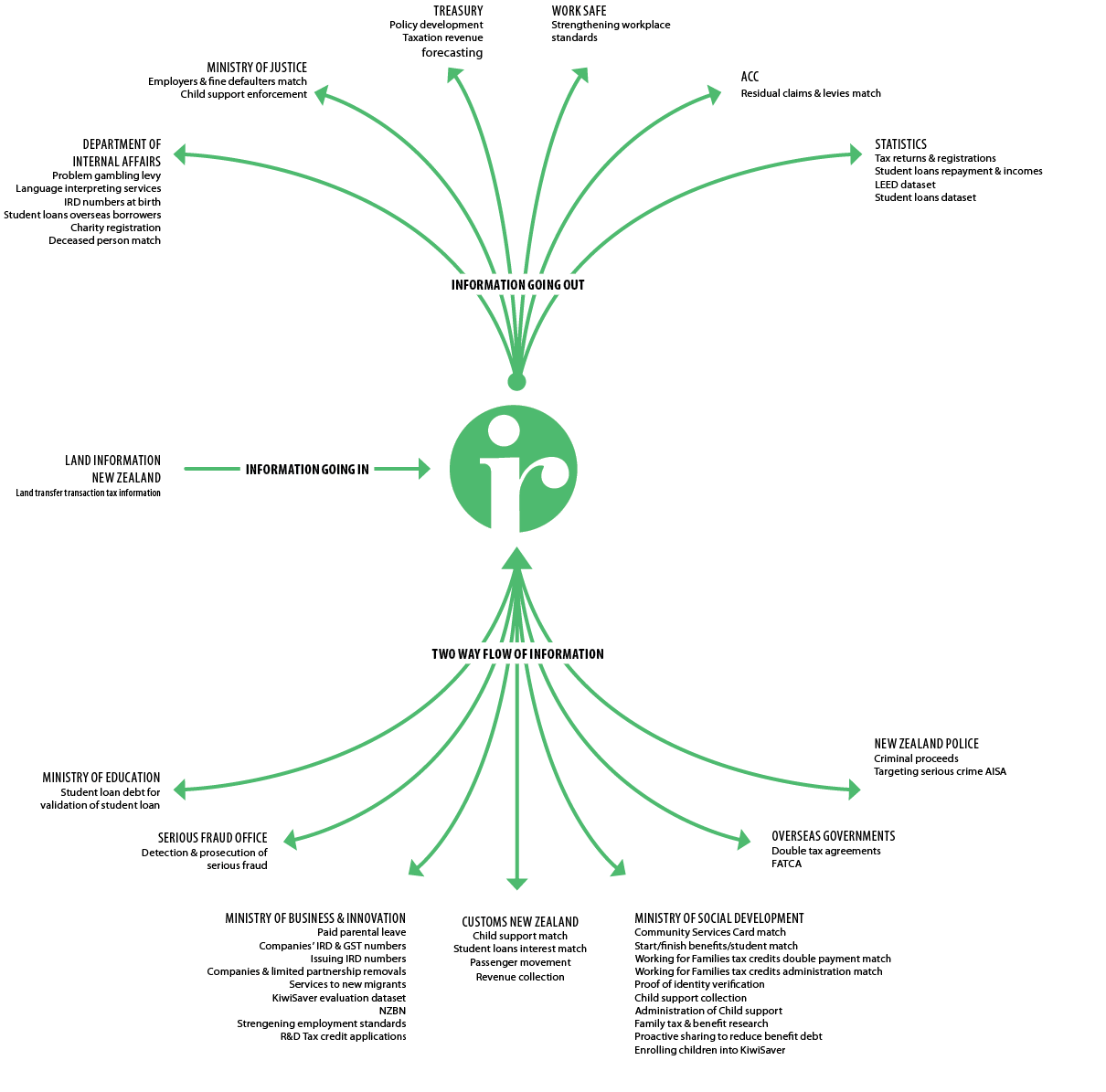

When information that identifies a taxpayer could be shared

Historically, taxpayer information has been protected because such protection is considered necessary to promote compliance and to act as a balance for broad information-gathering powers. While the commercial environment and society in general have changed significantly, confidentiality of taxpayer information remains important. However, that protection is far from absolute, with more and more exceptions being added to the “tax secrecy” rule. This has led to a legislative framework that could be seen to lack cohesion, transparency and clear unifying principles. The diagram on the following page gives an overview of the information currently able to be shared.

The Government proposes to create a new legislative framework for the protection and disclosure of taxpayer information. The new framework aims to provide greater transparency and cohesion when it is considered appropriate to disclose taxpayer information. It also aims to give greater flexibility to disclose information across government, if considered appropriate, in a transparent and controlled way. This is consistent with recent initiatives, such as the approved information-sharing agreement (AISA) framework within the Privacy Act.

The information-sharing principles and proposals discussed here are intended to apply regardless of the technology used. Current information sharing occurs using a range of technological solutions, but is generally the transfer of information to others. In the future, information sharing might also include access to Inland Revenue’s systems, controlled with appropriate permissions and monitoring.

| Flow of information with Inland Revenue | Organisation | Type of information |

|---|---|---|

| Information going out | Department of Internal Affairs | Problem gambling levy Language interpreting services IRD numbers at birth Student loans overseas borrowers Charity registration Deceased person match |

| Ministry of Justice | Employers and fine defaulters match Child support enforcement |

|

| Treasury | Policy development Taxation revenue forecasting |

|

| Work Safe | Strengthening workplace standards | |

| ACC | Residual claims and levies match | |

| Statistics | Tax returns and registrations Student loans repayment and incomes LEED dataset Student loans dataset |

|

| Information going in | Land Information New Zealand | Land transfer transaction tax information |

| Two way flow of information | Ministry of Education | Student loan debt for validation of student loan |

| Serious Fraud Office | Detection and prosecution of serious fraud | |

| Ministry of Business, Innovation & Employment | Paid parental leave Companies’ IRD and GST numbers Issuing IRD numbers Companies and limited partnership removals Services to new migrants KiwiSaver evaluation dataset NZBN Strengening employment standards R&D Tax credit applications |

|

| Customs New Zealand | Child support match Student loans interest match Passenger movement Revenue collection |

|

| Ministry of Social Development | Community Services Card match Start/finish benefits/student match Working for Families tax credits double payment match Working for Families tax credits administration match Proof of identity verification Child support collection Administration of Child support Family tax and benefit research Proactive sharing to reduce benefit debt Enrolling children into KiwiSaver |

|

| Overseas governments | Double tax agreements FATCA |

|

| New Zealand Police | Criminal proceeds Targeting serious crime AISA |

The four key exceptions to confidentiality cover disclosures:

- for purposes related to the tax system

- to the taxpayer or their agent

- relating to international agreements

- to other government agencies for non-tax-related purposes.

Exception 1: Disclosures for purposes related to the tax system

The primary reason for disclosing taxpayer information is for purposes relating to the tax system – in order to administer the laws for which Inland Revenue is responsible. This is why Inland Revenue collects information and will remain the primary exception to the new taxpayer confidentiality rule.

This will be a broad exception, and will consolidate specific exceptions that currently exist throughout the legislation. For example there are current specific exceptions relating to child support, KiwiSaver and student loans disclosures;[22] publication of product rulings[23] and approved organisations;[24] and prosecution of revenue-related offences (when the prosecution is under the Crimes Act or by the Serious Fraud Office).[25] Most, if not all, of these specific exceptions could be encapsulated within the exception for purposes relating to the tax system.

Exception 2: Disclosures to taxpayers and their agents

Disclosures to taxpayers and their agents is another area where significant change is not anticipated. A rule similar to that in the current Act will remain. Administrative processes to enable family members to access information (through a form of agent or nominated persons approach) similar to those used in Canada would be of benefit, particularly in relation to products such as Working for Families tax credits.[26] This could be managed as an extension of the existing nominated persons process, through which taxpayers are able to nominate someone to act on their behalf.[27] The Canadian approach has tiers of authorisation, so a taxpayer can authorise a nominated person to either view their information, or view and amend the information.

A key part of the modernisation of the tax system is enabling taxpayers to interact more easily with Inland Revenue. In many cases this will be through business software – such as the recent enabling of GST return filing directly from accounting software.[28] Inland Revenue in turn will be able to send information, confirmation and messages directly to taxpayers’ business software. The TAA was recently amended to clarify that the transmission of customer-specific information via business software provided and maintained by a software intermediary does not breach the secrecy provision.[29] This approach will be carried forward into the new rules.

Exception 3: International disclosures

Exceptions permitting international information sharing have appeared in the tax legislation since 1946, with the introduction of a provision permitting the disclosure of information under double taxation agreements (DTAs).[30] In order for DTAs to operate effectively, information needs to be exchanged between the tax jurisdictions concerned. Such use of information is usually regarded as consistent with the purpose for which it was collected: to correctly determine a taxpayer’s tax obligations.

The sharing of tax information across revenue agencies internationally is not a new concept. However, recent initiatives such as the Multilateral Convention on Mutual Assistance in Tax Matters, the US Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act and the OECD-led Automatic Exchange of Information (AEOI) have significantly increased the volume and automation of sharing, and will continue to do so in the future.

Sharing information under the DTA and Tax Information Exchange Agreement network will remain part of the core legislative framework, and no substantive change is proposed in this discussion document. Inland Revenue consulted earlier in 2016 on the implementation of AEOI,[31] and the Government has recently introduced legislation regarding foreign trusts, including disclosure of information about these trusts.[32]

Exception 4: Disclosures to other government agencies for non-tax-related purposes

The Government is committed to improving the public services available to New Zealanders. A key enabler of better public services is better use of data held by government. In considering the broader use of data, government is essentially balancing private rights (in the privacy or confidentiality of information) against the wider public good of efficient government, upholding the law and ensuring the right people receive the correct entitlements at the appropriate time.

Legislation already permits a considerable amount of cross-agency information sharing. However, there is no readily apparent consistent principle to these exceptions. Some are narrow, others broader, and in many cases legislative change has been made for the avoidance of doubt, even for minor changes to information exchanges.

The newer exceptions under sections 81A and 81BA are broader and allow sharing that meets certain criteria to be authorised by order in council.

- Section 81BA, introduced in 2011, is a specific Inland Revenue provision allowing Inland Revenue to share information with other government agencies. Such agreements can be entered into when the other agency is lawfully able to collect the information itself, but it is more efficient to obtain or verify the information from Inland Revenue.[33]

- Section 81A, introduced in 2013, allows Inland Revenue to use the approved information-sharing agreement framework set out in Part 9A of the Privacy Act. Such agreements can be entered into for the purpose of the provision of public services by government departments and may also include non-government organisations.[34]

These exceptions offer a greater degree of transparency, as the order in council and the underlying memorandum of understanding are often published. Such arrangements can also provide for public reporting on the information transfers. This is not the case for much of the information sharing authorised by specific legislative exceptions in section 81(4) of the TAA.[35]

Taxpayers are compelled to provide their information to Inland Revenue for reasons of public good – the administration of the tax system and other social policy provisions. The Government’s view is that it is appropriate to consider other “public good” uses of the information, particularly when these are consistent with or complementary to the direct reason the information was collected. This discussion document focuses on this type of information sharing. Greater care should be taken in considering uses of the information that move away from the public good, and the Data Futures Partnership will continue to explore these boundaries.

In many cases the purpose of proposed information sharing will be clearly within the public good criteria – for example, protecting public safety or ensuring people receive their correct entitlements from the government. In some cases the line between public good and private good may be less clear, or a proposal may contain elements of both.

Information sharing agreements – non-consented sharing

The Government proposes to modernise the information protection and disclosure framework in the TAA by moving to a regulatory model permitting information sharing (that meets certain legislated criteria) to be authorised by order in council.

A regulatory model would provide greater flexibility and timeliness to the implementation and amendment of information-sharing arrangements. The historical legislative model, involving specific exceptions for specific agencies, limited in many cases by purpose and even specific data points, is cumbersome and inflexible. Consideration was given to whether the new rules should require an order in council, or simply be managed through agreements between agencies. Given the importance of taxpayer confidentiality, the Government considers that the regulatory model is more appropriate, as it will retain Cabinet and Regulations Review Committee oversight of proposed agreements.

The aim of more flexible information sharing is to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of government, while not compromising the ability of Inland Revenue to perform its functions. It also aims to ensure information sharing is safe, proportionate and impacts on the confidentiality of information no more than is considered necessary to achieve the purpose of the sharing. To that end, the proposed model would permit sharing of Inland Revenue information for the provision of public services when:

- providing the information would improve the ability of the government to efficiently and effectively deliver services or enforce laws

- the information cannot easily or efficiently be obtained or verified from other sources

- the amount and type of information provided is proportionate given the purpose for which it is being shared

- the information will be adequately protected by the receiving agency

- sharing the information will not unduly inhibit the provision of information to Inland Revenue in the future.

When these tests are met, the Minister of Revenue may recommend an order in council be made to authorise the sharing. The order in council would set out the agency receiving the information and the broad purpose of the sharing. An underlying memorandum of understanding would then set out the details of:

- the classes or types of information to be shared

- how the information will be used

- how the information will be provided or accessed

- requirements for security, storage and disposal

- whether and how information can be further disclosed

- any review requirements, including disclosure of any breaches.

An important concern raised by several submitters on Towards a new Tax Administration Act was that any new cross-government information sharing should not enable other agencies to obtain information they would not otherwise be entitled to. The current section 81BA restricts information-sharing agreements to situations where the requesting agency is “lawfully able to collect” the information. A similar limitation will remain in the new rules. The intention is to ensure that an agency only obtains information necessary to carry out its functions.

In a similar way to the Privacy Act AISA model, and as with the proposal for consent-based sharing detailed below, the new framework proposes sharing “for the provision of public services” as opposed to specifying particular classes of organisation that can access the information. The Privacy Act defines a public service as “a public function or duty that is conferred or imposed on a public sector agency by or under law, or by a policy of the Government”.[36]

Example: areas where the new framework might be used

The proposed rules are targeted at the more efficient and effective operation of government. Broadly this would encompass information sharing to assist:

- more efficient delivery (or reduced cost) of a government-provided service or intervention

- reduced customer compliance burden for a government service or intervention

- increased accuracy of financial entitlements or obligations

- protection of the public revenue

- improved detection of serious illegal activities

- improved prevention of harm to citizens

- dealing with serious threat to public health or public safety.

A primary focus of the new rules would be areas where an AISA under the Privacy Act is not appropriate given the volume of non-personal (company or other entity) information that is to be shared.

Examples of current legislated information sharing that could in future be moved within the new framework include:

- sharing with ACC, in particular information that is used for levy setting for businesses

- sharing information with the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment to assist with their responsibilities under workplace legislation

- sharing information with the Department of Internal Affairs that relates to the administration of the Charities Act 2005.

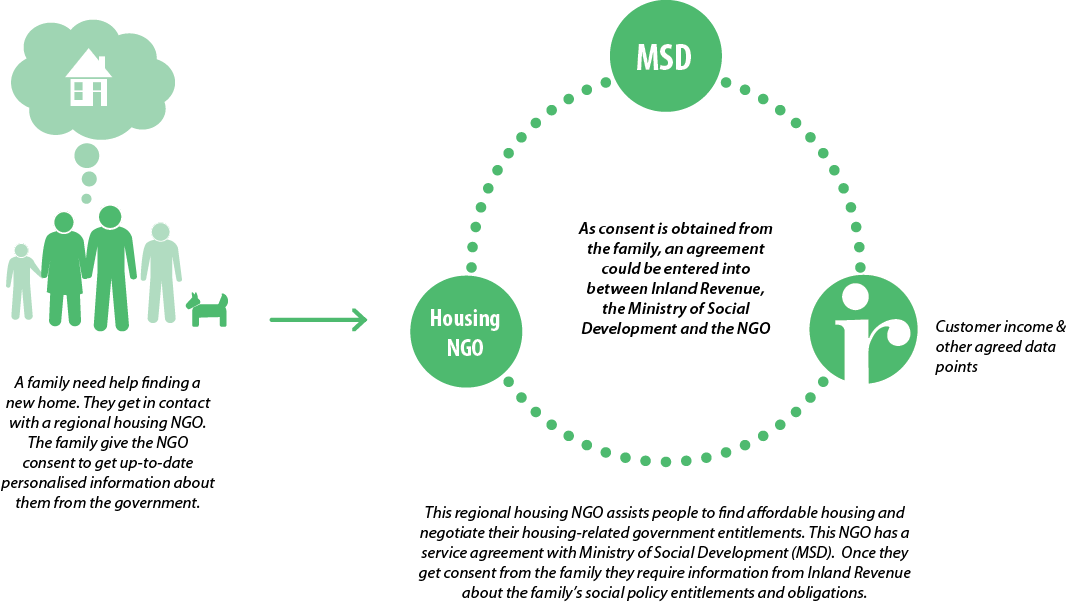

Consent-based sharing

In many cases information sharing is undertaken to improve the services offered to New Zealanders, and those affected would consent to their information being shared. Under the Privacy Act, individuals may authorise their information being shared, as privacy is theirs to waive. In contrast, confidentiality of tax information is an obligation imposed on Inland Revenue officers and the consent of the person to whom the information relates is no defence to breaching confidentiality.

In Towards a new Tax Administration Act the Government proposed that taxpayers be able to consent to the release of their information to other government agencies. This was considered a way to better enable taxpayers to participate in optional cross-government services, such as initiatives to simplify updating contact details across government agencies. A majority of submitters favoured this proposal, so long as it was limited to within government. The Government intends to proceed with this proposal.

The Government has recently announced the development of the “data highway” or Data Access Service as a key part of the social investment approach. Exchange of information is based on the informed consent of the individuals concerned. Allowing information to be shared by consent would enable Inland Revenue to become a part of the data exchange. Inland Revenue holds a significant amount of information, and this will be important to the successful functioning of the data exchange. Enabling consent-based sharing will not affect Inland Revenue’s ability to share information without consent if the authority to do so exists.

As these cases will involve taxpayer consent, the Government proposes that Inland Revenue be able to share information with other agencies for the provision of public services if a formal agreement for such sharing is in place. Such agreements would need to specify appropriate conditions for security and handling of information, and include processes to ensure that each taxpayer’s consent is properly obtained and recorded.

As with the AISA model in the Privacy Act, it is proposed that sharing be “for the provision of public services” rather than being strictly confined to being within government departments. This will enable, for example, Non-Government Organisations (NGOs) delivering public services on contract to a government department to also have access to the information if appropriate.

Example – consent-based sharing for social service provision

A regional NGO assists people to find affordable housing and negotiate their housing-related government entitlements. The NGO has a service agreement with the Ministry of Social Development to provide these services. Customers can be referred by the Ministry or approach the NGO directly.

In order to provide the best service to customers the NGO needs access to up-to-date personalised information. This includes income and other information (for example relating to other social policy entitlements and obligations) held by Inland Revenue. The NGO obtains the informed consent of its customers to access this information.

Inland Revenue, the Ministry of Social Development and the NGO (and potentially other NGOs offering the same service elsewhere) would sign an agreement. Inland Revenue could then provide information to the Ministry and/or the NGO on the customer’s income and any other agreed data points. The agreement would include provision for information security and proof that customers had properly given informed consent. (This type of data exchange might be facilitated by the Data Access Service discussed above.)

Transparency

The Inland Revenue website contains limited information about the use and disclosure of personal information as part of the privacy policy.[37] However, the information regarding information sharing is very high level and lists only some of the agencies that Inland Revenue shares with. Consistent with the greater transparency that forms part of the AISA model, and that discussed in Chapter 3 regarding certain information collection, the Government proposes that information sharing agreements under the new framework would be made public.

The Government also considers there is a benefit in making available to the public more consistent information about Inland Revenue’s information-sharing activity. This might best be done in Inland Revenue’s annual report and on the website. It could outline the agencies information is shared with and the reasons for sharing. Some indication of the volumes of information shared might also be included.

Transitional rules

Expanding the regulatory model to cover all cross-government information sharing will require an ongoing review of the existing provisions and the agreements sitting under those provisions. If possible, arrangements should shift to the new model; however, this is unlikely to happen seamlessly at the time of the enactment of the new provisions. In some cases, review and renegotiation of the agreements will be appropriate. It will be important to ensure that existing sharing is not inadvertently affected and therefore transitional provisions will be required to move from the old to the new rules.

Enforcement of taxpayer confidentiality

The TAA contains offence provisions for both Inland Revenue officers and certain other persons who fail to maintain secrecy.[38] The Government proposes to retain a similar penalty for Inland Revenue officers who knowingly breach the proposed confidentiality rule. The retention of a penalty will confirm the ongoing importance of confidentiality.

The current rules are less clear in relation to other persons who have access to, or receive, Inland Revenue information. In many circumstances people with access to Inland Revenue information are required to sign secrecy certificates; however, this does not apply in all cases. Moreover, in a world of ever-expanding information sharing, the administration of secrecy certificates for every person who will come into contact with Inland Revenue information may be logistically difficult.

Agreements between Inland Revenue and agencies that information is shared with contain clauses regulating the use of information. For example, the agreement between Inland Revenue and New Zealand Police contains provisions regarding the security, use and disclosure of information shared. It also provides for processes in the event of a breach, including permitting the suspension of information sharing while breaches are investigated. These are important provisions and will continue to feature in such agreements.

The Government recognises that tax information can be very sensitive, and its receipt should come with particular obligations. In Australia the comparable legislation provides that confidentiality follows the information, and therefore anyone who obtains protected information and then discloses it otherwise than in accordance with the legislation, commits an offence. This is, in effect, a clearer and more consistent application of the current rule in section 143D of the TAA.

The Government proposes the rule in the TAA be simplified to state that anyone with access to information subject to the confidentiality rule who knowingly improperly discloses the information, be subject to a penalty. The current penalty for both Inland Revenue officers and others with access to Inland Revenue information is imprisonment for a maximum of six months, a maximum fine of $15,000, or both.

[1] See for example the recent speech to IPANZ given by the Secretary to the Treasury, Gabriel Makhlouf “Trust, Transparency and the Facts – Driving Forces Behind Modern Government” (14 March 2016) and to the Third Data Hui by the Minister of Finance, Hon Bill English (19 April 2016).

[2] Knight v Commissioner of Inland Revenue [1991] NZLR 30 (CA).

[3] The Forum comprises academic, private and public sector expertise, chaired by John Whitehead, former Secretary to Treasury and World Bank Executive Director. See media release of Hon Bill English and Hon Maurice Williamson, 12 February 2014, https://www.nzdatafutures.org.nz/news#government

[4] https://www.nzdatafutures.org.nz/sites/default/files/first-discussion-paper_0.pdf. The initial work of the Data Futures Forum is now being followed up by the Data Futures Partnership.

[5] Social investment is about improving the lives of New Zealanders by applying rigorous and evidence-based investment practices to social services. It means using information and technology to better understand the people who need public services, finding out what works, and then adjusting services accordingly. Much of the focus is on early investment to achieve better long-term results for people and help them to become more independent – see further http://www.treasury.govt.nz/statesector/socialinvestment and linked pages.

[6] See http://www.customs.govt.nz/news/resources/customs-and-excise-act-review/Documents/CandEAct1996Review-Information%20Management%20and%20Disclosure%20Cabinet%20minute.pdf

[7] Public attitudes to the sharing of personal information in the course of online service provision, Lips, Eppel, Cunningham & Hopkins-Burns, 2010.

[8] The Impact on the Integrity of the Tax System of IR Sharing Information with Other Public Sector Organisations: New Zealand Businesses’ Perspective, Inland Revenue National Research & Evaluation Unit, 2013 http://www.ird.govt.nz/resources/f/2/f271bb6e-871d-48a2-b3b0-d82029afedf1/info-sharing-bus-report-pso.pdf

[9] Available at https://www.privacy.org.nz/news-and-publications/surveys/privacy-survey-2016/

[10] Understanding Attitudes Towards Business Data Secrecy, Inland Revenue National Research & Evaluation Unit and UMR, 2016 http://www.ird.govt.nz/aboutir/reports/research/

[11] Schedule 1 to the Search and Surveillance Act 2012 sets out the various legislative powers of agencies to which that Act now applies. There are 79 Acts listed in the Schedule and while many of them detail powers that require a warrant to execute, some agencies have quite broad and/or invasive powers that do not require a warrant to exercise or that exist outside the Search and Surveillance Act.

[12] https://www.privacy.org.nz/assets/Files/Reports/OPC-Transparency-Reporting-report-18-Feb-2016.pdf

[13] See for example recent articles following revelations of the “Panama Papers”: Van Beynan, M., “It’s our business what other people earn and pay in tax” Dominion Post Weekend (16 April 2016, p. 6); Lewis, M., “After Panama leak, Norway’s open tax system inspires some” Yahoo Finance, (14 April 2016) https://www.yahoo.com/news/panama-leak-norways-open-tax-163303068.html

[14] See for example the conclusion in Devos, K. & Zachrisson, M. “Tax compliance and the public disclosure of tax information: an Australia/Norway comparison”, eJournal of Tax Research (March 2015, 13(1), 108–129) – “It is surprising how little is known about the compliance effect of public disclosure and consequently more empirical studies are desperately needed.”

[15] Blank, J.D. “USA”, in Kristofferson, Lang, Pistone, Schuch, Staringer, Storck (eds.) Tax secrecy and tax transparency: the relevance of confidentiality in tax law, Peter Lang Publishing, 2013, p. 1163.

[16] Tax Laws Amendment (Confidentiality of Taxpayer Information) Bill 2010: Explanatory Memorandum, example 2.11 at paragraph 2.20.

[17] “Swan reveals mining tax revenue” SBS News (8 February 2013) http://www.sbs.com.au/news/article/2013/02/08/swan-reveals-mining-tax-revenue

[18] The release of such information is currently generally dealt with by way of section 81(1B), followed by consideration of any OIA factors indicating the information should be withheld.

[19] Compare the Privacy Act, which has an exception for the protection of the public revenue (in addition to a “maintenance of the law” exception) to the principle that personal information should not be disclosed.

[20] Freedom of Information Act 1982 (Cth) sections 37(2)(b), 47E(a), (b), and (d).

[21] Freedom of Information Act 2000 section 30.

[22] Tax Administration Act 1994, section 81(4)(fc), (g), (gb), (gba), and (u).

[23] Tax Administration Act 1994, section 81(4)(m).

[24] Tax Administration Act 1994, section 81(4)(mb).

[25] Tax Administration Act 1994, section 81(4)(b) and (c).

[26] Revenue Canada allows differing levels of authorisation for representatives – either full legal representation with the ability to view and change details or more restricted access where information can be disclosed but not changed – see http://www.cra-arc.gc.ca/tx/ndvdls/tpcs/chng_rps/lvl-eng.html

[27] See also the discussion in chapter 5 regarding intermediaries that do not meet the definition of a tax agent.

[28] As set out in chapter 5, the Government does not currently consider accounting or payroll software developers to be intermediaries between taxpayers and Inland Revenue in the context of the proposals in that chapter. However, for confidentiality rule purposes, some provision is required and this fits best within the general area of exceptions relating to the transfer of information to the taxpayer.

[29] Taxation (Transformation: First Phase Simplification and Other Measures) Act 2016 section 122(5), inserting new section 81(4)(ld) in the Tax Administration Act 1994.

[30] Land and Income Tax Assessment Amendment Act 1946, section 5(5).

[31] See http://taxpolicy.ird.govt.nz/topical-issues/implementing-aeoi

[32] See http://taxpolicy.ird.govt.nz/news/2016-08-08-simpler-business-taxes-tighter-foreign-trust-rules-new-tax-bill

[33 Two orders in council are in place under this provision – the first provides for sharing information with the Ministry of Social Development and the second with the Accident Compensation Corporation.

[34] Inland Revenue is party to two approved information sharing agreements. The first allows Inland Revenue to obtain address information from the Department of Internal Affairs (being information received in the course of passport applications) for the purpose of contacting overseas-based student loan borrowers. The second agreement is to enable Inland Revenue to share information with the New Zealand Police, for the purpose of combating serious crime.

[35] The exception is sharing done under “information matching agreements” under Part 9 of the Privacy Act. These arrangements are subject to monitoring and reporting by the Office of the Privacy Commissioner.

[36] Privacy Act 1993 section 96C.

[37] See http://www.ird.govt.nz/about-this-site/privacy/privacy-policy.html