Review of the implementation of the simplified filing requirements for individuals’ legislation

Agency Disclosure Statement

This Regulatory Impact Statement has been prepared by Inland Revenue.

The question addressed in this statement is whether the implementation of legislation for simplified filing requirements for individuals (SFRI), which was enacted in 2012 and is not due to take effect until the 2016-17 year, is a sound investment.

Inland Revenue considers that a significant proportion of the projected revenue gains of $217 million from SFRI will be eroded due to the changes expected under Inland Revenue’s Business Transformation (BT) Programme, which is aimed at simplifying New Zealand’s tax administration system. As a result, the SFRI legislation should not be implemented.

The policy underlying the SFRI legislation was set three years ago.At that time, the Government was concerned about the inherent tension between individuals who are not required to file an income tax return and those who are. This tension gives rise to complexity in meeting obligations and creates fairness and equity concerns for some individuals. Individuals who are required to file an income tax return may have a tax debt in one year and receive a refund in another year. For individuals who are not required to file, however, there is no incentive to file an income tax return in order to square-up in years of tax debt, but they can easily claim any available refunds. The practice of filing income tax returns in those years in which an individual is due a refund is referred to as “cherry picking” and has become prevalent especially with the introduction of personal tax summary (PTS) intermediaries. This practice has also resulted in a situation where large amounts of revenue are being paid out in refunds, without a reciprocal obligation on taxpayers to pay any tax debt.

SFRI legislation is aimed at addressing the fairness and equity concerns by removing the ability for people to cherry pick and by removing the requirement for others to file income tax returns.

Inland Revenue’s current BT thinking for individual salary and wage earners is for more streamlined processes with salary and wage earners’ information being provided by third parties such as employers and banks to Inland Revenue and Inland Revenue undertaking the necessary calculations. This should lead to a more accurate PAYE structure, which means fewer people in a refund or tax debt position at the end of the year. If it were adopted, the current BT vision will represent a significant change in direction in dealing with end of year tax debts and refunds and draws into question the assumptions on which the SFRI legislation is based, and therefore whether it should now be implemented.

Inland Revenue’s review of the implementation of the SFRI legislation concluded that the benefits and policy outcomes sought by SFRI can be delivered by BT but in a more coherent way that aligns with our vision of a proactive and efficient tax administration.

The preferred option is to repeal the SFRI legislation. This is intended to reduce compliance costs and confusion for a large group of individuals who would need to change their interactions with Inland Revenue under SFRI and then again under BT. We acknowledge, however, that there may be a negative effect on public trust and confidence in the tax administration system due to major changes being enacted and then repealed prior to implementation.

Repealing the SFRI legislation will also reduce administration costs for Inland Revenue as it will avoid creating resource contention issues across Inland Revenue’s entire change portfolio and BT. In particular, highly skilled FIRST resources would have been needed to work on SFRI at a time when these resources would be required for BT.

The most significant dependency of the analysis is the ability of Inland Revenue to deliver the BT programme by the indicative timeline. If Inland Revenue does not implement the BT programme and deliver the expected benefits of an improved PAYE structure by 2019-20, then this will affect Inland Revenue’s assessment of the SFRI investment.

No public consultation was undertaken on the option to repeal the SFRI legislation. We considered there would be very little benefit in consulting with the affected groups because repeal would be taxpayer-friendly, and the affected groups would not have adjusted their behaviour in line with the SFRI changes as these changes are not due to take affect for another three years. Even so, Inland Revenue hosted a conference “A Tax Administration for the 21st Century” in June 2014. Some tax practitioners and representatives from PTS intermediaries who attended the conference questioned the relevance of the SFRI legislation given the current BT vision and supported the repeal of the SFRI legislation.

There are no other significant constraints, caveats or uncertainties concerning the regulatory analysis undertaken.

The preferred option does not impact private property rights, restrict market competition, or override fundamental common law principles.

The status quo option will reduce the net amount of refunds available to individuals and this will also affect the current business model of the personal tax intermediary market. These implications were canvassed in the July 2011 Regulatory Impact Statement Simplifying filing requirements for individuals and record-keeping requirements for businesses.

Ron Grindle

Acting Deputy Commissioner, Change

Inland Revenue

22 July 2014

STATUS QUO AND PROBLEM DEFINITION

Background

1. New Zealand’s current tax administration is heavily reliant on paper-based processes such as the annual return-filing system. These processes are both costly and time consuming as they increase taxpayer contacts with Inland Revenue. In the last 10 years, the number of contacts with taxpayers has increased significantly and the resulting processing has created considerable pressure on the administration of the tax system. The increase in contacts is due in part to the expansion of Inland Revenue’s responsibilities into social policy administration and the requirement for social policy recipients to file an income tax return.

2. Also driving the increase in contacts is the large number of individuals able to self-select to file an income tax return in years in which they are due a refund. This has resulted in a significantly increased workload for Inland Revenue as people re-enter the annual filing system. Some taxpayers are required to file an income tax return (and pay any tax debts) simply because they are, for example Working for Families (WfF) recipients, whereas other taxpayers who are not required to file, have the ability to “cherry pick” the years they filed on the basis of whether they are to receive a tax refund or have a tax debt. This practice has become prevalent especially with the introduction of personal tax summary (PTS) intermediaries and has also resulted in a situation where a large amount of revenue is being paid out, without a reciprocal obligation on taxpayers to pay any tax debt.

3. The simplified filing requirements for individuals (SFRI) initiatives introduced in 2012 are aimed at addressing fairness and equity concerns by stopping people cherry picking, and removing the requirement for WfF recipients to file income tax returns.

Previous Cabinet decisions

4. In June 2010, Cabinet agreed to the release of the discussion document, Making tax easier, which outlined various proposals for transforming the way that Inland Revenue engages with employers, businesses and individuals [EGI Min (10) 11/10].

5. In August 2011, in response to feedback on the discussion document, several initiatives were developed and considered by Cabinet, namely:

- an “e” awareness campaign and enhancements to Inland Revenue’s online service for individuals (no legislation was required);

- amalgamating two major tax returns, the IR 3 and personal tax summary (PTS) returns;

- delinking the requirement to file a personal tax return if the person is receiving Working for Families (WfF) tax credits. (“WfF delinking”); and

- requiring a person to file income tax returns for the past four years, if they are not otherwise required to file, but they choose to do so, to prevent cherry picking of refunds (“4+1 square-up”).

6. The three legislative initiatives were to take effect from 1 April 2015.

7. Cabinet agreed to the package of initiatives and their inclusion in the Taxation (Annual Rates, Returns Filing, and Remedial Matters) Bill. [EGI Min (11) 17/14, CAB Min (11) 30/8]

8. In early April 2012, it was identified by Inland Revenue that if the package of initiatives were to be implemented it would have placed significant pressure on Inland Revenue’s ability to implement any future change initiatives, including the Student Loan Redesign Project (which was already underway) and the Child Support Reform Programme (which was in the initial stages of implementation).

9. At the time, Cabinet was advised by Inland Revenue that there was a way to deliver a less resource intensive and system-reliant solution for the package of initiatives, but it would involve not proceeding with the amalgamation of the IR 3 and the PTS returns. Cabinet agreed that in the interest of maintaining maximum organisational stability for and flexibility within Inland Revenue, the amalgamation of the two returns was removed from the Bill. Cabinet also agreed that the implementation dates for the two remaining legislative initiatives; WfF decoupling and the 4+1 square-up would be deferred for two years (the 2016-17 income year). [EGI Min (12) 6/17, CAB Min (12) 12/6C]

10. The Cabinet decisions were included in the officials’ report that was delivered to the Finance and Expenditure Committee on 30 April 2012. There were no other significant changes made to the package of initiatives in the following Parliamentary stages.

11. The Bill containing the SFRI initiatives was enacted in November 2012.

12. The “e” awareness campaign and enhancements to Inland Revenue’s online service for individuals are well underway. Key initiatives under this campaign include eUptake specific marketing to migrate more taxpayers to Inland Revenue’s digital space and direct taxpayer education on Inland Revenue’s online services and reduce use of cheques.

High-level review of the implementation of the SFRI legislation

13. In December 2013, the Minister of Revenue directed Inland Revenue to undertake a high-level review of the benefits, costs and impacts of implementing the SFRI legislation and to consider the viability of the SFRI investment in the light of the recent progress on the Business Transformation (BT) Programme. This direction was in response to concerns raised by Inland Revenue about its ability to implement the legislation by the legislative dates and the need to seek further funding to implement the legislation.

14. Inland Revenue’s review concluded that the likely outcomes from BT will mean that implementing the SFRI legislation is now no longer a sound investment. This conclusion was based on Inland Revenue’s examination of the benefits and costs of implementing SFRI and how BT will affect the policy outcomes sought under SFRI.

SFRI impacts

15. The estimated revenue gains expected from SFRI were $217 million over a period of seven years, starting from the 2016-17 year. These gains mainly result from the 4+1 square-up initiative, as individuals will no longer be able to cherry pick the years in which to file an income tax return based on whether they receive a refund. They will instead be required to file tax returns for the last four years in addition to the current year in which they have chosen to file an income tax return.

16. The estimated cost to implement SFRI is in the vicinity of $35 million to $45 million. Inland Revenue currently has $14.463 million to implement the SFRI legislation[1]. A further $20 million to $30 million will be required to implement the legislation.

17. By the end of the 2018-19 year (the year before BT is expected to start delivering benefits linked to streamlining PAYE), Inland Revenue would have spent a cumulative $35 million to $45 million implementing the SFRI legislation for estimated revenue of $36 million.[2] This means the return on investment for the period up to 2018-19 would be between $0.80 to $1.03 for every dollar spent.

18. The original analysis undertaken in 2011 determined that the 4+1 square-up would affect 310,000 individuals and the WfF decoupling change would affect 330,000 individuals. The 4+1 square-up group has now increased to over 500,000 due to the efforts of PTS intermediaries. The impacts of these initiatives were canvassed in the July 2011 Regulatory Impact Statement Simplifying filing requirements for individuals and record-keeping requirements for businesses.

How Business Transformation affects SFRI

19. Inland Revenue is currently embarking on a Business Transformation (BT) programme, a once-in-a-generation opportunity to simplify New Zealand’s tax administration system. This is more than a “computer” project – rather, it is a comprehensive transformation of Inland Revenue’s operating model. This is likely to include future policy changes.

20. The outcome roadmap for BT noted by Cabinet in August 2013 displays the desired outcomes of transformation, grouped in four stages. Stage 1 focuses on securing digital services including streamlining the collection of PAYE information and is due to be delivered between years 1 to 6 of the programme. Stage 2 of BT envisages streamlining business taxes and will include work on improving the accuracy of PAYE deductions. Stage 3 will focus on the delivery of social policies Inland Revenue administers. Stage 4 looks at other taxes.

21. Inland Revenue’s current BT thinking for salary and wage earners is for more streamlined processes with salary and wage earner information being provided to Inland Revenue by third parties and Inland Revenue undertaking the necessary tax calculations. This should lead to a more accurate PAYE structure, which means fewer people in a refund or tax debt position at the end of the year. With real-time information and analytical tools, refunds would automatically be given out removing the need for people to file an income tax return to get a refund, and debts would be automatically rolled over to new periods, so “cherry picking would be non-existent.

22. If it were adopted, the current BT vision would represent a significant change in direction in dealing with end of year under and over payments of PAYE and draws into question the assumptions on which the SFRI legislation are based, and therefore whether it should now be implemented.

23. On current plan, it is envisaged BT will deliver a more improved PAYE structure by the 2019-20 year. This would make PAYE more accurate and make a significant difference to reducing, over time, the number of individuals who would need to square-up at the end of the year.

24. The benefits arising from BT stages 1 and 2 that are relevant to the consideration of SFRI are as follows:

- BT stage 1 will deliver more accurate PAYE, therefore reducing the need for square-ups by improving the accuracy of tax codes being used by customers, providing near real-time validation of tax codes, and integrating information collection requirements and rules for PAYE into payroll software to minimise errors on a pay-period basis. Inland Revenue’s recent experience with student loans has shown that getting people on the right tax code early reduces down-stream errors and increases repayment levels.

- BT stage 2 will follow with further improvements in PAYE, including integrating withholding requirements and rules for PAYE into payroll software to increase the accuracy of withholding deductions on a pay-period basis and deploying upfront analytical tools to validate and verify data.

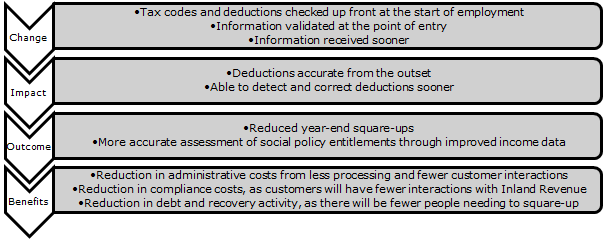

25. The BT changes for individual salary and wage earners and their expected impacts, outcomes and benefits are set out in diagram 1. Improving the accuracy of tax codes being used by individual salary and wage earners and providing near real-time validation of tax codes would mean deductions are accurate from the outset. This will mean reduced year-end square ups and more accurate assessment of social policy entitlements through improved income data. The benefits from BT would include reduced administrative costs for Inland Revenue and compliance costs for individuals.

Diagram 1

26. The revenue gain estimates for BT stage 1 indicate financial benefits of $500 million–$700 million and economic benefits (improved customer experience and compliance cost savings) of $1 billion–$2.2 billion over a 10-year period. Most of these benefits are expected to be realised from 2019-20 onwards. Inland Revenue is not in a position to provide a detailed yearly break-down at this time.

27. The estimates of the BT benefits will be validated as part of the first detailed design business case, which is expected to be completed in November 2014. This process will include consultation with customers and third parties to confirm the nature, extent and timing of these benefits.

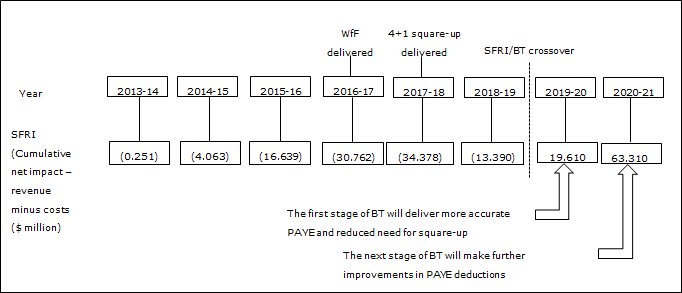

28. Diagram 2 highlights the interplay between BT and SFRI. The bottom row of boxes indicates the cumulative net effect of the SFRI investment for the period from 2013 to 2021. The first year in which the SFRI investment becomes positive (the estimated revenue exceeds estimated costs) is the 2019-20 year, and this is when BT is also expected to start delivering its benefits of more accurate PAYE and reduced need for individuals to square-up. The positive outcomes which were expected to arise from SFRI in 2019-20 and beyond will not now be realised as the revenue gains from SFRI will cease from that point.

Diagram 2

29. In the 2019-20 year the SFRI benefits will cease as the SFRI policy settings are superseded by the BT policy settings.

30. The intersection of SFRI and BT would also potentially cause significant taxpayer confusion given that the two projects are operating to significantly different policy settings. This could lead to increased taxpayer contacts with Inland Revenue as taxpayers require more assistance to understand the changes and this would give rise to increased costs for both parties.

31. Inland Revenue’s review concluded that the SFRI legislation should not be implemented on the basis that the revenue gains of $217 million from SFRI will be eroded by BT. On current plan, BT will deliver a more improved PAYE structure, which will make PAYE more accurate and substantially reduce the number of individuals with a material refund or tax debt at the end of the year. Consequently, as SFRI was only ever seen as a “back-end” solution (i.e., stopping people “cherry picking” thereby reducing the incentive to file) to a “front-end” problem of inaccurate PAYE deductions during the year, the policy outcomes sought under SFRI will not be realised from 2019-20 onwards.

OBJECTIVES

32. The objectives of this review are to ensure that:

a) changes made to the current tax administration for individual salary and wage earners align with the BT vision of a proactive and efficient tax administration;

b) the Government’s revenue base is maintained;

c) Inland Revenue can maintain its organisational stability and flexibility so that it can manage its change portfolio including BT;

d) individual salary and wage earners have certainty of tax treatment and compliance costs are minimised.

33. The key objective in this analysis is objective (a). This is because the BT vision will set the future framework in which all policy changes will need to comply with. There may need to be a trade-off between the objective of maintaining the Government’s revenue base and the other objectives. For example, implementing the status quo will address the cherry picking issue (and the revenue leakage) but it is also inconsistent with the BT vision and is likely to put pressure on Inland Revenue to manage its current change portfolio.

REGULATORY IMPACT ANALYSIS

34. Inland Revenue’s high-level review considered a range of options for addressing the problem definition and achieving the objectives. These options ranged from implementing the SFRI legislation in whole, in part and not at all.

35. We also considered scaling back the SFRI legislation in order to minimise implementation costs. However, as the underlying premise of the SFRI initiatives did not align well with the BT vision, the scale back options were not further explored. Furthermore, although it would have been possible to implement the 4+1 square-up change without the need to deliver WfF delinking, it would not have been sensible to deliver WfF delinking without the 4+1 square-up as it would still have allowed WfF customers to cherry pick.

36. The options analysed in this RIS are:

- Option 1 – implement the SFRI legislation as enacted (status quo). This option would commence with the development of a better business case, which would examine both the solution and costs in more detail and establish how this initiative will be funded.

- Option 2 – repeal the SFRI legislation. Under this option taxpayers will continue to have the ability to cherry pick until the BT measures are implemented in 2019-20.

Analysis of options

37. The tables below set out our assessment of the two options against the objectives and summarises the impacts of each of option relative to the status quo.

| Option | Meets objectives | Impacts | Net impact | |||

| Economic and fiscal impacts | Administrative and compliance impacts | Equity and risks | ||||

1. Implement the SFRI legislation |

b | Government | Estimated revenue gains of $217 million over 7 years starting from the 2016-17 year were expected from SFRI These gains will be eroded by BT from the 2019-20 year onwards – this means that the expected estimated revenue gains from SFRI would actually be $36 million only $5 million has been counted in the current baselines (up to 2017-18) |

The cost to implement SFRI is in the vicinity of $35 million to $45 million Inland Revenue currently has $14.463 million to implement SFRI – it will need a further $20 million to $30 million to complete implementation Increase in administration costs for Inland Revenue due to more taxpayer contacts as people will require assistance to understand the SFRI changes and then the subsequent BT changes |

Fairer for WfF recipients as they will be treated like other non-filing individuals Maintains revenue flows up to 2018-19 Inland Revenue will be seeking a further $20 - $30 million additional funding to make changes that would yield only $36 million in revenue Changes would be made to Inland Revenue’s current FIRST system that could compromise system integrity Inland Revenue will have resource contention issues across its entire change portfolio including BT. In particular, it is highly likely that skilled FIRST resources will be required to work on SFRI but will be needed on BT |

Not recommended Does not address the problem definition or achieve most of the stated objectives |

| Salary and wage earners and personal tax summary intermediaries | Individuals do not have the ability to cherry pick the years in which they have a refund across the four years – therefore, there would be a reduction in the net amount of refunds available for salary and wage earners Personal tax summary intermediaries will also be affected as there will be fewer people seeking their services |

Increase in compliance costs and confusion for a large group of individuals who would need to change their interactions with Inland Revenue under SFRI and then again under BT - this could affect their willingness to comply with their tax obligations and overall trust in the tax administration Increase in compliance costs for PTS intermediaries as they will need to change current business model and systems |

||||

| Option | Meets objectives | Impacts | Net impact | |||

| Economic and fiscal impacts | Administrative and compliance impacts | Equity and risks | ||||

2. Repeal the SFRI legislation |

a, c, and d | Government | Although the projected revenue gains were $217 million only $36 million will be expected due to BT The revenue cost is $5 million. (This is because only $5 million of the expected estimated revenue gains from SFRI have been “counted” in current baselines, which extend out four years to 2017-18) |

Avoids the cost of $35 million to $45 million to implement SFRI Inland Revenue must return $6.293 million in appropriated funds to the Crown Decrease in administration costs for Inland Revenue due to fewer taxpayer contacts as people will not require assistance to understand the SFRI changes and then the subsequent BT changes |

Although this option does not maintain the revenue flows from SFRI the impact on the government’s baselines is only $5 million due to the four-year baseline period The groups directly affected will likely see the repeal of SFRI as a positive measure but those who currently are unable to cherry pick will view repeal of SFRI as unfair Possible negative effect on public trust and confidence in the tax administration system due to major changes being enacted and then repealed prior to implementation |

Recommended Addresses the problem definition and achieves most of the stated objectives |

| Salary and wage earners and PTS intermediaries | Individuals will continue to have the ability to cherry pick the years in which they have a refund until the BT changes take effect in 2019-20 PTS intermediaries will be unaffected until the BT changes take effect in 2019-20 |

Decrease in compliance costs and confusion for a large group of individuals as they would not need to change their interactions with Inland Revenue under SFRI and then again under BT Decrease in compliance costs for PTS intermediaries as their current business model will be unaffected until BT changes take effect in 2019-20 |

||||

Social, environmental or cultural impacts

38. There are both social and cultural impacts associated with the options considered above. The SFRI initiatives address concerns of fairness and equity with the current tax administration system. Although some taxpayers are required to file (and pay any tax debts) simply because they are, for example WfF recipients, other taxpayers who are not required to file, have the ability to “cherry pick” the years they filed on the basis of whether they were to receive a tax refund or had a tax debt. Repealing the SFRI legislation will mean that the current tax administration will continue to be unfair for those taxpayers that are required to file and may negatively affect their trust and confidence in the current tax administration system. This could in turn impact on taxpayer compliance overall.

39. There are no environmental impacts associated with any of the options.

Net impact of all options

40. The preferred option to repeal the SFRI legislation (option 2) addresses the problem by removing an inefficient means to reforming the tax administration for salary and wage earners in the light of the BT vision. It also achieves most of the objectives – that is, it ensures changes that are inconsistent with the BT vision are not made, and compliance and administrative costs are minimised overall.

41. Inland Revenue does not support the status quo (option 1) because it does not address the problem and is inconsistent with the current BT vision.

CONSULTATION

42. Inland Revenue has not undertaken public consultation on the option to repeal the SFRI legislation. We considered there will be very little benefit in consulting with the affected groups on the preferred option of repealing the SFRI legislation on the basis that repeal will be see as taxpayer friendly, and these groups would not have adjusted their behaviour in line with the SFRI changes as these changes are not due to take affect for another three years.

43. In June 2014, Inland Revenue hosted the conference “A Tax Administration for the 21st Century”. Some tax practitioners and representatives of PTS intermediaries who attended the conference questioned the relevance of the SFRI legislation in the light of BT vision and supported its repeal.

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

44. Inland Revenue recommends that the SFRI legislation be repealed, as:

- it is now no longer a sound investment given the BT programme of change;

- on current plan, BT will deliver the benefits of SFRI (i.e., stop “cherry picking” and reduced return filing leading to fewer customer contacts) but will do so in a more proactive and efficient way.

- the intersection of SFRI and BT is likely to cause compliance costs and confusion for taxpayers given that the two initiatives are operating under significantly different policy settings;

- it will help Inland Revenue to better manage its entire change portfolio and BT.

45. Given the above, we consider the repeal of the SFRI legislation to be preferable to implementing the legislation. Furthermore, repealing the SFRI legislation would reduce administrative and compliance costs overall. The status quo option would have the opposite effect.

IMPLEMENTATION

46. Repeal legislation should be included in the next available taxation bill, which is scheduled for introduction in November 2014.

47. Although the SFRI legislation is enacted it still has a further three years before it takes effect. Therefore, repealing the legislation as soon as possible will ensure that there is sufficient time to signal to the affected groups that the SFRI changes are not being implemented. The Minister of Revenue will issue a media statement on the proposed repeal when the tax bill containing the repeal legislation is introduced into the House. Once enacted, Inland Revenue will communicate the repeal as part of its business as usual communications relating to legislative changes.

48. Repealing the SFRI legislation will not negatively impact the affected groups. Individuals will continue to have the ability to cherry pick the years in which they have a refund and WfF recipients will file annual income tax returns but most of these recipients are either in a refund position and will file anyway, or are required to file under another tax law. Additionally, repealing the SFRI legislation should avoid taxpayer confusion that could have resulted from the intersection of SFRI and BT – two reforms operating under significantly different policy settings.

MONITORING, EVALUATION AND REVIEW

49. There will be opportunities for interested parties and the general public to comment on the SFRI legislation and its repeal if the preferred option is adopted, both through submissions on the taxation bill containing the repeal, and as part the BT programme. This is because Ministers instructed officials to ensure that the policy outcomes that the SFRI legislation sought to address are included in the BT programme.

50. In general, Inland Revenue’s monitoring, evaluating and reviewing of new legislation takes place takes under the GTPP. The GTPP is a multi-stage tax policy process that has been used to design tax policy in New Zealand since 1995. The final stage in the GTPP is the implementation and review stage, which involves post-implementation review of the legislation, and the identification of any remedial issues. Opportunities for external consultation are also built into this stage. In practice, any changes identified as necessary for the new legislation to have its intended effect would generally be added to the Tax Policy Work Programme, and proposals would go through the GTPP.

[1] This amount comprises appropriated funds of $6.263 million and delegated authority for Inland Revenue to spend up to $8.2 million from its capital reserves.

[2] The $36 million is based on the revised revenue gains expected from SFRI. It comprises $4 million in 2016-17, $7 million in 2017-18, and $25 million in 2018-19.