Chapter 6 - A better customer experience using digital services

- Customers’ needs will be met by a range of high-quality digital services

- Most customers will choose to use digital services

- Some customers cannot move to digital services

- Some customers could move to digital services, but will choose not to

- Summary of proposals

Chapter 4 notes that while some digital services have already been delivered, their scope and sophistication are limited by the constraints of Inland Revenue’s outdated system. New technology would remove these system constraints, and allow the development of new and better digital services.

This chapter looks at how new technology could deliver a better customer experience using digital services, based on the principles set out in chapter 5.

CUSTOMERS’ NEEDS WILL BE MET BY A RANGE OF HIGH-QUALITY DIGITAL SERVICES

(Principle: No one size fits all)

As noted earlier digital services must be designed with the customer at the centre. They will need to be easy to access and use, fast, secure and reliable.

Digital technology is constantly evolving. A package of services which is designed for customers will need to be sufficiently flexible to keep pace with technology changes.

Customers have indicated that they want a seamless experience through all available channels. For example, if they are filing a return online, they might want to be able to get help via telephone or email, or even complete their return over telephone or email, if they strike an unexpected difficulty. Customer-focused services need to allow customers to change the way they want to complete interactions, carrying across the information they already provided from one channel to another.

Customer needs and their ability to use digital services also differ, both by customer type and by the interaction which they are having with Inland Revenue. The requirements that a large business has for dealing with Inland Revenue about income tax are likely to be quite different from the requirements an individual will have. In these kinds of situations, it is likely that different types of digital services will need to be developed to provide a customer-focused experience and recognise that “no one size fits all”. In some instances new services may be better provided by third parties than directly by Inland Revenue.

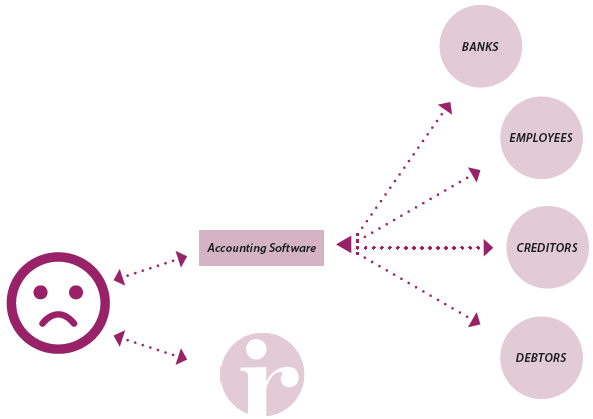

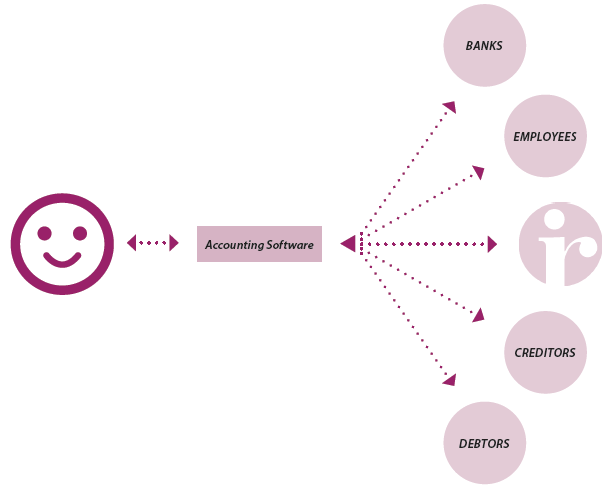

CURRENT STATE

Business customers need to interact with both their accounting software and Inland Revenue to meet their obligations

FUTURE STATE

Business customers only need to interact once with their accounting software to meet their obligations

A good example of different customer needs might be for businesses that have PAYE reporting obligations. A very small business using a simple manual payroll for one employee might be best served by something like an online portal which retains basic information into which they can enter current pay information. This could be provided by Inland Revenue, or a payroll software provider may provide this free as a marketing tool.

Some customers’ needs will be best met through delivery by third parties

For businesses that already use computerised payroll systems, the best kind of digital service might be one delivered by the private sector. This could integrate PAYE filing into their payroll accounting software removing the need to deal with PAYE filing obligations separately.

This kind of integration with existing processes – in particular, business accounting systems – is a way of delivering services designed with the customer foremost. This kind of approach could deliver significant benefits to customers by eliminating the need for them to deal with routine tax matters as a separate exercise. Tax compliance could be integrated into business processes like weekly pay runs for PAYE or monthly sales reporting for GST.

To integrate with existing processes, Inland Revenue would need to ensure it has close and collaborative working relationships with those who develop business accounting systems, and others who deal with individuals and businesses, such as financial institutions.

Interactions differ, as well as customers

Individuals and businesses will have different expectations of digital services. A person will have different expectations of customer-focused services, depending on the kind of tax interaction they require. Returning to the large business payroll example, direct integration with its payroll accounting system may be the best way to deal with the routine transfer of PAYE information.

This may not be business’s preferred mechanism for a non-routine interaction. For example, if the Human Resource Manager and Chief Financial Officer become aware that the company’s previous PAYE treatment of redundancy payments has been incorrect they might want discuss this concern directly with Inland Revenue, notwithstanding that their routine PAYE is dealt with automatically through their payroll software.

This need to discuss complex or sensitive matters might be best met by a different digital channel, such as an online enquiry portal or a dedicated email channel, or a non- digital channel such as a telephone contact centre.

THE MEANING OF DIGITAL BY DEFAULT

Being digital by default means producing digital services that are so compelling and easy to use that those who can do so will. Digital by default is also a shift in the culture of government so that it thinks “digital" first. Only then can the government create the outstanding digital services that people will embrace. "Digital by default" does not mean replacing services with a digital-only option (e.g. completely closing down the face-to-face approach or other alternatives). It is about encouraging people who can to turn to digital services first.

The Government’s rural broadband initiative aims to connect 86% of rural homes and businesses to broadband at peak speeds of at least 5 Mbps by 2016. However, a segment of the population will continue to have very limited internet access.

MOST CUSTOMERS WILL CHOOSE TO USE DIGITAL SERVICES

If individuals and businesses are offered good quality, secure, customer-focused digital services for interactions appropriately carried out across digital channels (including in partnership with third parties such as business accounting software providers), the majority can be expected to move to these services in the timeframe which best fits their own personal or business needs. They would likely do this because they identify the benefits that digital services would provide, such as greater convenience, certainty or reliability.

Secondly, as noted in Chapter 4, despite the constraints of ageing technology, Inland Revenue’s ability to deliver quality digital services is recognised.

Finally, and most compellingly, uptake of Inland Revenue’s digital services has, to date, been strong. As noted, the online service for individuals, myIR, has 1.7 million registered customers. In December 2014, 86% of payments to Inland Revenue were made through electronic channels.

There are a number of strategies that Inland Revenue could develop to encourage customers to adopt digital services. One could be to move to a “digital by default” strategy, in particular for new customers (or existing customers who are starting to use a new form of interaction – such as registering for GST). A good example of this would be to use email to communicate with customers who have consented to this form of communication.

Where a high-quality digital service exists (whether delivered by the private sector or directly by Inland Revenue), customers should be directed to that option as a matter of course. Non-digital alternatives should be de-emphasised in favour of the digital offering. This is simpler for customers compared with the alternative of adopting a non-digital option initially and subsequently facing the cost and disruption of moving to a digital option.

When a new digital service has been established, Inland Revenue could expressly promote it, in particular to customers who are using the non- digital alternative.

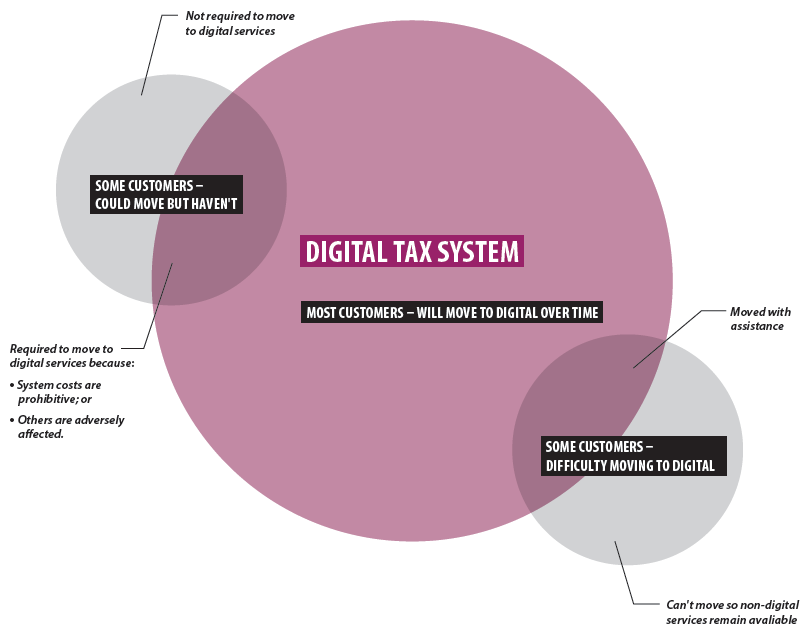

SOME CUSTOMERS CANNOT MOVE TO DIGITAL SERVICES

Even if high-quality digital services targeted at all kinds of customers and appropriate tax interactions are built, there will inevitably be some customers who cannot adopt them.

Reasons for this could include:

- They do not have the skills or knowledge to use digital technology.

- They do not have access to digital technology – they may be financially constrained, or perhaps live in an area of New Zealand which does not have internet access.

The United Kingdom has adopted an approach to “assisted digital” which provides that government will:

- work with the private sector, voluntary sector and other parts of the public sector to provide assisted digital support

- try new ways of working to provide assisted digital support efficiently and effectively

- introduce a service standard, so assisted digital support is of consistently high quality

- consider introducing a quality mark for approved/accredited providers so users can be confident in the support they will receive.

For this group, the relevant principle is that tax compliance and access to entitlements are critical. Their ability to comply with their tax obligations and access their entitlements must remain even if the majority of other customers are carrying out those interactions through digital options.

Two approaches could be offered to customers who cannot move to digital services. Both approaches would be operated simultaneously, with different customers falling into each approach.

Assistance

(Principle: Tax compliance and access to entitlements are critical)

A subsidy is currently provided to support the use of payroll intermediaries by certain small employers. Employers with less than $500,000 of PAYE deductions per year are entitled to a subsidy of $2 per employee, per pay period, for up to 5 employees, if they use a recognised payroll intermediary.

The first approach is to provide some specific, targeted assistance to enable these customers to use digital services. There are two reasons for providing this kind of assistance – and both will raise additional costs for Inland Revenue:

- Digital services bring a range of benefits to customers compared with non-digital services, as identified earlier. It is fair that customers who would otherwise not be able to access these benefits be supported to do so.

- As noted in Chapter 5, Inland Revenue’s cost in dealing with digital interactions is lower than for non-digital interactions. Because society as a whole bears the cost of administering the tax system, (it is funded out of government revenue), providing additional support to enable customers to move to digital options delivers a benefit to everyone.

The nature of assistance will vary from service to service and will need to be developed based on users’ needs. Some services will have more people who require assistance than others – for example, business services may need less support than a digital service which supports a user group with a lower level of digital skills. Some examples of this kind of assistance could be:

- Recognition that online services require appropriate offline support – the New Zealand strategy for digital public services requires that it should be easy for New Zealanders to get sufficient support when using digital options.

- Kiosks – Places where people who do not have internet access could go to use an internet-connected computer (whether provided by government or otherwise). Some specific assistance or even a digital service specifically designed for people who are not experienced internet users could even be provided.

- Assistance to develop digital capability – Inland Revenue’s staff already help customers, including small businesses, to understand their tax obligations and how to use existing digital services.

- Subsidies – For example, to support businesses adopting accounting software which integrates tax and accounting functions.

Other government agencies are also moving to provide digital services, and are likely to face the issues described above, with the same customers. Several of the forms of assistance described above could most efficiently be provided on a cross-government basis. This would also deliver a simpler and better customer experience.

Non-digital services should be available for some customers

(Principle: Tax compliance and access to entitlements are important)

The second approach to this customer group is to acknowledge that, whatever support and assistance Inland Revenue or wider government might be able to offer, some customers will still not be able to directly use digital services. For example, a business in a remote location with no broadband internet access will not be able to use business accounting software which integrates tax obligations online even if the cost is subsidised. These customers will still need to manage their interactions with Inland Revenue through non- digital services.

This could be done by ensuring existing non-digital services are provided. However, depending on the nature of some of Inland Revenue’s system changes, retaining existing services in their current form in the future may not be possible. In these cases, some process to convert non- digital to digital information might be required. Inland Revenue could carry out this process itself, or arrange for a third party to supply it.

SOME CUSTOMERS COULD MOVE TO DIGITAL SERVICES, BUT WILL CHOOSE NOT TO

(Principle: Change will not be imposed without careful consideration of the costs and benefits)

These customers are not those subject to the constraints preventing adoption of digital services set out above but for whatever reason, have chosen not to move to digital services.

As noted earlier in this chapter, once Inland Revenue has developed a comprehensive portfolio of high- quality digital services, the majority of customers who can adopt those services, are over, time expected to “vote with their feet” and move to digital services. The category of customers who can adopt those services but who choose not to is therefore expected to be small, and will diminish over time.

It is likely that digital and non-digital services will sit alongside each other for some time, with the choice of channel being largely left to customers. There are two possible reasons for customers who could use digital channels, but who choose not to.

Additional and avoidable cost imposed on tax administration system

The cost of delivering tax administration through digital services is typically lower than by non-digital equivalents. Because tax administration is funded out of government revenue, everyone bears the cost. Everyone benefits by having the most efficient tax administration system. Accordingly, allowing some customers to impose a cost on wider society because of a choice they made, rather than out of necessity would need careful consideration.

The Commissioner of Inland Revenue would need to work alongside these customers to support and encourage them to adopt digital services. The Commissioner also has the ability to determine the range of services which are offered, under her powers to administer the tax system.

Those powers are set out in section 6A of the Tax Administration Act 1994, and give the Commissioner the duty to collect the highest net revenue over time, having regard to:

- the resources available to the Commissioner;

- the importance of promoting compliance; and

- the compliance costs incurred by taxpayers.

This provision requires the Commissioner to compare the additional costs these customers would impose on the tax system by not using digital services with the costs these customers would face in moving to digital services, and using those digital services on an ongoing basis. The Commissioner could make the decision under this provision to remove non-digital services for some customers for some transactions.

As well as the additional and avoidable costs imposed on the tax system, the reluctance of these customers to use digital channels may also be imposing additional and avoidable costs on other agencies which rely on information provided by Inland Revenue. The Commissioner may also wish to take these costs into account in her approach to the use of digital channels by these customers.

Any legislation which currently prescribes non-digital services would need to be amended to be neutral – see Chapter 7.

Others are being denied the benefits of the new tax administration system

As Inland Revenue’s transformation programme progresses, the levels of service offered to everyone affected by the tax system in some way are expected to significantly improve. In some circumstances, those improvements will be contingent on Inland Revenue receiving information through digital channels – for example, employers, who provide PAYE information about their employees to Inland Revenue.

PAYE information is critical to determining matters like social policy entitlements of employees. The tax system is likely to evolve so that Inland Revenue can deliver better services to these employees (such as correct calculations of Working for Families entitlements for each pay period, removing any need for annual square-ups), when their employers are working with Inland Revenue via digital services.

Another example could be tax intermediaries, who provide information to Inland Revenue on the tax affairs of their clients. Inland Revenue may be able to deliver better services to these clients – such as allowing them to check their tax position online in near real-time, when their tax agents are working with Inland Revenue via digital services.

As noted above, as well as this information being critical to determine the tax position of others, it may also be used by other government agencies to determine other liabilities. For example, information provided by employers to Inland Revenue is used by ACC to determine liability for earner account levies for employees.

The Commissioner of Inland Revenue would need to work alongside those who provide information to support and encourage them to adopt digital services. Again, the Commissioner’s powers under the Tax Administration Act will allow her to restrict the availability of non-digital channels for some transactions carried out by those who provide information if this was appropriate, although this would need to be evaluated against compliance costs for those affected.

The Government sees the satisfactory resolution of this issue as critical to ensuring that the New Zealand economy as a whole derives maximum benefit from the Government’s investment in the new tax administration system, and the delivery of this benefit to some sectors of the economy should not be prevented by the reluctance of others to adopt digital services.

Accordingly, the Government proposes to make it clear that any decision by the Commissioner to require these customers to use digital channels has the full force of law.

SUMMARY OF PROPOSALS

Most customers will voluntarily move to digital services, provided Inland Revenue builds (or works with the private sector to build) digital services that meet customers’ needs.

Some customers will initially be unable to adopt digital services. Others will be able to adopt digital services if assistance is provided; and for the remainder, some non-digital services will need to be provided.

Some customers will be able to adopt digital services, but may choose not to. This may be an issue if the cost of providing non-digital services for them becomes prohibitive, or others (such as their customers or employees) are denied the benefits that a modernised tax administration could otherwise deliver. For both categories, the Commissioner of Inland Revenue could work alongside affected groups to encourage and support them to adopt digital services. The Commissioner has power under existing legislation to require the use of digital services if necessary. However, the Government thinks that where others are adversely affected by someone not using digital services, the Commissioner's requirement to use digital channels should have the full force of the law.

CUSTOMER GROUPS

QUESTIONS FOR READERS

- Do you think you would move to digital services for your tax interactions, if high-quality digital services which met your needs were offered? Even in this situation, can you foresee any interactions which you would not want to carry out using digital services? What would they be?

- What could Inland Revenue do to create an environment that supports new customers to adopt digital services?

- What could Inland Revenue do to support existing customers using digital services?

- Do you agree Inland Revenue should provide specific assistance to enable some customers to use digital services? What forms do you think that assistance might take? How long do you think that assistance should be provided for?

- Who do you think will not be able to move to digital services, even with specific assistance?

- Do you agree that when some people have a digital services option available, but by not using it are imposing a cost on everyone, they should be supported, encouraged and, if necessary, ultimately required to use digital services?

- Do you agree that where some people (such as employers and tax agents) who choose not to use digital services, and by doing so are denying others (such as their employees or clients) the benefits of the new tax administration system, that first group should be required to use digital services?

- Do you agree that the Commissioner should use her existing powers under the Tax Administration Act, which include the requirement to have regard to compliance costs, to facilitate the move to digital services?