Chapter 2 - Current landscape

Summary of policy principles used in considering the tax treatment of an employee expenditure paymentIn considering in this issues paper the appropriate tax treatment of an employee expenditure payment, the following principles have been taken into account:

* Other than when it relates to a capital expense |

2.1 This issues paper builds on the themes of Budget 2010. These included the need to improve the integrity of the tax system and social assistance programmes so that individuals pay their fair share of tax, and social assistance is targeted at those in genuine need. The paper is one of a series of papers over the past two years that focus on these themes and objectives, the others being: Social assistance integrity; defining family income and Recognising salary trade-offs as income. It also builds on analysis undertaken in the 2007 issues paper, Tax-free relocation payments and overtime meal allowances.

2.2 The key focus has been on the taxation of labour income and the recognition of this income and other benefits provided by employers to their employees in exchange for labour services when determining eligibility for social assistance, in as comprehensive a way as practicalities allow.

2.3 This paper does not, however, identify or seek to address any major gaps in the tax base that are giving rise to revenue risks. Rather, it assumes that the main challenge for taxing employee expenditure payments is to provide greater certainty for both taxpayers and Inland Revenue.

2.4 Inland Revenue does not hold detailed information about how much employers pay by way of employee expenditure payments. The observations in this issues paper are, therefore, of necessity based on our discussions with individual businesses and key business representatives that have a range of employers making employee expenditure payments.

2.5 Discussions with employers and representative groups suggest that the employee expenditure payment rules work well for employers for the most part, but there are some significant interpretive issues that mean a policy response is needed. This paper attempts to address these concerns.

Development of employee expenditure payments and their tax treatment

2.6 Over the years there have been a number of changes to the tax legislation applying to employee expenditure payments. Their purpose has been to ensure that any payment for private expenditure is taxed, or are a consequence of changes to other taxing provisions applying to employees.

2.7 A key change was the introduction of the fringe benefit tax (FBT) rules in 1985, which make a clear distinction between monetary payments, that should be taxable to the employee under the income tax rules, and non-cash goods and services that should be taxable to the employer under FBT. The reform included the repeal of the employee deduction rules.[1} and introduced the definition of “expenditure on account of an employee”.

2.8 Before 1995, the Commissioner of Inland Revenue could determine whether and to what extent any employee expenditure payment constituted a reimbursement of expenditure incurred by the employee in gaining or producing his or her assessable income. The payment was, to the extent determined, exempt from tax.[2}

2.9 Dealing with these requests was, however, a resource-intensive process. The approach also did not fit easily with the move to self-assessment. As a result, the approach was changed through legislation in 1995.[3} Since then, it has been the employer’s responsibility to make a judgement on what the correct tax treatment is for an employee expenditure payment.

2.10 The general exemption provision for employee expenditure payments was also changed in 1995. The Commissioner discretion was replaced with a test that makes the expenditure or payment by the employer non-taxable to the extent it relates to expenditure for which the employee would be allowed a deduction but for the employment limitation. These changes meant that certain employee expenditure payments were taxable to the extent that the expenditure they met were private (or domestic) or capital in nature. Rules were also introduced so employers could use a reasonable estimate when determining the expenditure that an employee would be likely to incur.

2.11 A more detailed summary of the current legislation relating to employee expenditure payments can be found in Appendix B.

Employee expenditure payments in practice

2.12 As a general observation, in recent times Inland Revenue and employers have been looking to simplify and reduce their processing costs, aided by computerisation and new technologies. Historical work practices have been brought up to date and employment practices changed. Nevertheless, employee expenditure payments must still be inputted into the payroll before they can be paid, which gives rise to significant compliance costs.

2.13 There has also been a change in the shape of New Zealand industry[4} over the past 20 years, with a shift towards service industries and away from more traditional forms of employment such as manufacturing. Service industries have experienced the highest levels of employment growth (particularly business and financial services), stimulated in part by technological change.

2.14 As a result of these changes and business pressures, anecdotal evidence shows that there has generally been a significant reduction in the number, nature and variety of employee expenditure payments over the years. Employers have also tried to reduce business costs by making employee expenditure payments simpler. For example, by paying an allowance to meet estimated business travel expenses rather than reimbursing exact expenses or by providing employees with a corporate credit card to pay for business expenses up-front that can then be settled by the employer.

2.15 Working conditions have also changed, with flexible working arrangements, new communication technologies and computerisation leading to an increase in working outside the traditional office environment. Employees may receive payments to reimburse the additional costs.

Employee expenditure payments

2.16 The term “employee expenditure payment” describes a range of payments to reimburse or otherwise meet an employee’s expenditure.

2.17 It includes the payment of a cash allowance. In this context, allowances describe a payment to an employee which is in addition to salary and wages, as compensation for expenditure that the employee incurs or is likely to incur in connection with their employment. An allowance can be paid in advance of the employee incurring the expenditure and may be based on a reasonable estimate of the expenditure that the employee is likely to incur.

2.18 An employee expenditure payment also includes a payment to reimburse actual expenditure incurred by the employee or expenditure on account of an employee to settle the employee’s liability with a third party. The expenditure may be directly related to the employee’s job or may be related to the employer’s business. These sorts of payments are normally paid in arrears either directly to the employee or to a third party to settle the employee’s liability.

2.19 Types of employee expenditure payments that are commonly made and specifically addressed in this document include meals, accommodation, communication and clothing payments.

2.20 Under the current legislation, when an employee expenditure payment is made, provided it is to meet an expense incurred in earning the employee’s employment income, it is not taxable unless there is a private or capital element in the expenditure. In the latter circumstances, the payment may be taxable in part or in full.

Payments that are outside the scope of the review

2.21 Employers may also pay allowances relating to unusual conditions of service. These types of allowances do not relate to the employee incurring expenditure. They might, for example, include allowances to recognise additional skills an employee has to offer their employer in carrying out their employment duties.

2.22 Other examples of these sorts of allowances are payments to compensate for difficult or unpleasant working conditions or for taking on additional responsibilities.

2.23 These sorts of payments are likely to be additional rewards for an employee providing their labour in specific circumstances, reflecting market conditions and the need to pay more in order to get the right person to do the job. As such, they are treated as employment income in the same way as wages or salary. These types of allowance normally present few difficulties in determining the correct tax treatment and are not discussed further in this paper.[5}

2.24 There are a number of other scenarios, when employers make payments to meet additional expenses arising in connection with the employee’s job, which are not covered by this review. These include overtime meal allowances, additional sustenance allowances, additional transport costs and certain expenses as part of a work-related relocation package. These payments are already subject to existing tax exemptions[6} and are not discussed further in this paper.

Policy questions

2.25 In determining the appropriate tax treatment for a particular employee expenditure payment, our starting point is that the best approach is to consider all such payments, regardless of the nature of the underlying expenses they are intended to meet. Our preference is, therefore, to include all employee expenditure payments whether they are related specifically to the employee’s job or more broadly to the employer’s business. Otherwise, there would be boundary issues around what is included and what is excluded.

2.26 To resolve potential areas of uncertainty around borderline issues, our preference is to have clear objective tests to determine what is taxable and what is not for the most common types of payments. For other types of payments not covered by these specific tests, the general approach outlined in this issues paper in chapter 6 would apply (subject to any options for change).

2.27 In considering the appropriate tax treatment for a particular employee expenditure payment, the first question is whether it covers a private expense. Unless it covers a private expense, there will usually be no taxable element. An outgoing is of a private nature if it is exclusively referable to living as an individual member of society or is an ordinary living expense. Examples of expenditure that are often of a private nature include food, clothing and accommodation.

2.28 References in this paper to a private expense include the private element of an expense. However, when the private element is low in value and solely incidental to a work expense or low in value and hard to measure it may be preferable, in order to reduce compliance and administrative costs, to ignore it.

2.29 Salary substitution can arise in a range of instances, although it is more evident when an amount of salary has been traded off or given up for non-cash benefits. By contrast, with the exception of accommodation payments, the employee expenditure payments being considered in this issues paper are unlikely, for the most part, to form part of a salary substitution. However, it will be important to ensure that any changes do not introduce any new incentives for salary substitution.

2.30 When goods or services that are low in value and hard to measure are provided to an employee and fall below a minimum threshold, they are often exempt from fringe benefit tax (FBT).[7} This is for compliance and administrative costs reasons. However, exempting equivalent cash payments in this way would pose a fiscal risk. Therefore, while it would not be practical to tax all low in value and hard to value employee expenditure payments, a different approach is needed.

2.31 Account should also be taken of anything the employee contributes, such as an employee contribution to accommodation costs, which reduces the value they receive from their employer.

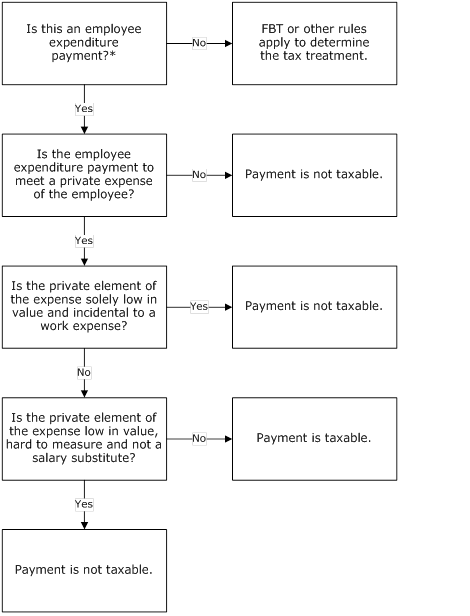

2.32 Pragmatic solutions to the main employee expenditure payments that balance the broad salary substitution concerns against the need for workable tax outcomes are considered in this paper. The approach we have taken is illustrated in the flowchart at the end of this chapter.

Other considerations

2.33 There are a number of other considerations that have been taken into account in developing the best options for reform. These are:

- The tax outcome should not be unduly influenced by the payment mechanism – While an employer will often pay an allowance in anticipation of an employee incurring expenditure, they might also reimburse actual expenditure that has already been incurred or settle an employee’s bill. Alternatively, rather than paying cash they might arrange for goods or services to be provided. Whichever mechanism is chosen, as far as possible, the tax outcome should be the same, without significantly different compliance costs for employers.

Rules should be easy to understand and apply – Certainty and simplicity are desirable because employee expenditure payments are mostly dealt with by human resource and payroll staff in larger companies and the wages clerk in smaller companies, who may have little tax expertise. Employers are also reluctant to make judgements about, or delve into, their employees’ personal affairs in determining whether a particular payment is taxable.

However, there is a trade-off between providing certainty (with, for example, an objective “bright line” test to determine what is taxable and what is not), against fairness and flexibility with a more subjective test (for example, by reference to what is reasonable). - The impact of any changes to the current rules on employer/ employee agreements and the time needed to adapt these – Many payments are the subject of historical employment agreements negotiated between employers, employees and their trade unions. These agreements may take time to change and, therefore, transitional issues might need to be considered in implementing any changes that arise as an outcome of this review.

- The outcome of the review should be revenue-neutral –While the outcome of the review is not intended to raise revenue, it must be recognised that there is limited scope for relaxing the current legislation.

Policy principles for reviewing employee expenditure payments

Note:

The terms used in this flowchart are generic and are not based on current legislation or case law definitions.

The flowchart reflects the general policy principles, which should apply so that an employee expenditure payment should not be taxed in the hands of the employee, provided any private expense is low in value and incidental to any work expense or hard to measure and not a salary substitute.

These principles are likely to be relevant to all types of employee expenditure payment, although initially focused on the main types identified in this paper.

*“Employee expenditure payment” covers all payments, whether related to the employee’s job or more broadly to the employer’s business, and includes allowances to cover future estimated expenditure, actual reimbursement and expenditure on account of an employee payments.

1 Previously in the fourth schedule of the Income Tax Act 1976.

2 Sections 73(2) and 73A of the Income Tax Act 1976 and then sections CB 12(1) and CB 13 of the Income Tax Act 1994.

3 Changes were made through the Income Tax Act 1994 Amendment (No 2) Act 1995.

4 Department of Labour. Workforce 2010 – a document to inform public debate on the future of the labour market in New Zealand: Department of Labour, March 2001.

5 The tax treatment of an additional skills allowance is wholly separate to any consideration of the tax treatment of any payment by the employer to reimburse an employee for costs they have incurred in gaining the particular skills.