Chapter 3 - Definition of “family scheme income” for Working for Families: proposed reforms

3.1 The gaps in the definition of “family scheme income” and the arrangements that raise social assistance integrity concerns and the proposed legislative solutions to include certain types of income as family scheme income for WFF purposes are discussed in detail below. The amended definition of “family scheme income” would apply to all applicants for WFF tax credits from 1 April 2011.

3.2 Any changes to family scheme income used for WFF purposes would also have an impact on determining entitlements to community service cards for persons with dependent children. Furthermore, this paper proposes that for student allowance purposes the current parental income test be replaced with the family scheme income definition.

Trustee income

The issue

3.3 Currently, the income of a trust can be taxed as trustee income at a final rate of 33% and the trust can later distribute this income to beneficiaries of the trust tax-free. While beneficiary income is taxable at the beneficiaries’ level, and therefore included for WFF purposes, the distributed trustee income is not included in the taxable income of beneficiaries.

3.4 The main integrity concerns involve a closely held family trust situation when the parents are settlors of the trust and can receive tax-free distributions from the trust. Although the distributed trustee income is used to meet the family’s living expenses, this income is not included for WFF purposes. The income of a trust can be earned directly by the trust carrying on a business or receiving investment income. A trust can also own a company that carries on a business.

Business income

3.5 The common structure of a trust that owns a company running a business can have the effect of increasing WFF entitlements. The company’s net income is subject to company tax and then paid as a dividend to the trust, where it is retained and taxed as trustee income. Tax-free distributions from the trust subsequently made to beneficiaries are not included for WFF purposes. Therefore, the family receives the benefit of the business income although this is not reflected in their taxable income. For WFF purposes, a family’s entitlement would be based on the salary or wages received from the company and any beneficiary income received from the trust.

3.6 Another feature of the trust-owned company situation could involve a family member working for the company drawing a nominal salary. This structure inflates their WFF entitlements by reducing their taxable income while increasing the company’s net income, which is not currently attributed to them but which ultimately benefits them.

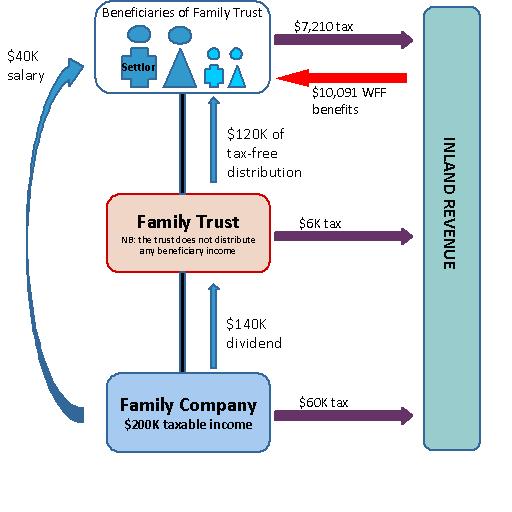

Example[7]

Peter and his spouse have two dependent children. Peter is the sole income earner in his family and earns $40,000 per annum working for Family Company. Peter is also a sole director of Family Company.

Family Company is wholly owned by Family Trust. Peter is both the settlor and a trustee of Family Trust. Peter’s family are discretionary beneficiaries of Family Trust.

The taxable income of Family Company is $200,000, on which it pays $60,000 tax. Family Trust receives a $140,000 imputed dividend from Family Company. Family Trust then distributes $120,000 (which has already been taxed as trustee income) to the family.

The family receives $152,790 ($32,790 salary after tax + $120,000 distribution from Family Trust) excluding WFF tax credits, but the distribution from Family Trust is not counted for WFF tax credit calculation purposes. As a result, the family receives around $10,091 WFF tax credits per year. If the business income of Family Company were included in the family’s income, they would not be entitled to any WFF tax credits.

This arrangement is illustrated in the following diagram:

3.7 Interposing a trust between the closely held company and individuals circumvents the current rules for attributing retained income of a closely held company to its shareholders for WFF purposes. If a trust is inserted between the family members and the company, the attribution rules in section MB 4 of the Income Tax Act 2007 do not apply to the income of the company.

3.8 Similarly, if the family business is owned and operated directly by a trust rather than by individuals or by a company, the trading income of the trust which is taxed as trustee income is not included for WFF purposes.

Investment income

3.9 Investment income, such as interest earned by a trust, that is taxed as trustee income and then distributed tax-free to beneficiaries is also currently not included for WFF purposes.

Proposed solution

3.10 Trustee income, whether distributed to beneficiaries or retained by the trust, is available to meet day-to-day living expenses in the case of many family trusts. Therefore, trustee income in such closely held situations – including the net income of a company controlled by a family trust – should be included in a person’s family scheme income.

3.11 Attributing trustee income to individuals for WFF purposes is consistent with the current rule for attributing income from closely held companies. The attribution of trustee income should be limited to closely held situations because these are where the main integrity concerns arise.

3.12 For the purpose of determining the family scheme income of a person for an income year, if the person is a settlor of a trust, the following income would be included:

1. the trustee income (net income less income distributed as beneficiary income) of the trust in the income year; and

2. the net income of a company controlled by the trust would be included in the trustee income that is attributed under 1.

3.13 Accordingly, the trustee income of a trust, including the net income of a company controlled by the trust, would be attributed to the individuals who are the settlors of the trust.

3.14 The policy objective is to attribute trustee income to the individual(s) who directly or indirectly determine the application of the income or body of the trust. This individual is most likely to be the settlor of the trust.

Definition of “settlor”

3.15 The definition of “settlor” in section HC 27 of the Income Tax Act 2007 would be used for the purposes of this attribution rule. The term “settlor” has a wide meaning and is defined broadly as a person who transfers value to a trust. The definition of settlor is further extended by the provisions of section HC 28, the most significant of which are:

- when a company makes a settlement, any shareholder with an interest of 10 percent of more in that company is treated as a settlor in relation to that settlement as well as the company itself;

- when a trustee of a trust (the first trust) settles another trust (the second trust), the settlor of the second trust is treated as including any person who is a settlor of the first trust; and

- when a person has any rights or powers in relation to a trustee or settlor of a trust which enables the person to require the trustee to treat them (or a nominee) as a beneficiary of the trust, the person is treated as a settlor of that trust.

3.16 The definition of settlor is used extensively in the Income Tax Act 2007 and its wide meaning is consistent with the settlor-based focus of the trust taxation rules in that Act.

3.17 The definition of settlor, in conjunction with the nominee look-through rule in section YB 21 of the Income Tax Act 2007, does not include professional advisors acting on behalf of clients and other persons such as friends and family members who simply allow their name to be listed as the settlor on a trust deed. The main focus of the definition is on persons who provide the trust property. It is therefore the client of the professional advisor, or the person the friend or family member is acting for, who would be treated as the settlor.

3.18 Because the focus of the proposed attribution rule is on closely held situations, charitable trusts would be excluded from the attribution rule. A charitable trust under the Income Tax Act 2007 is required to be registered as a charitable entity under the Charities Act 2005 and is therefore subject to the regulatory requirements of that Act. Similarly, any settlements for the benefit of local authorities should be excluded.

3.19 Registered superannuation schemes that are trusts should also be excluded from the proposed rule. This is because they primarily provide retirement benefits and accordingly their income is not available to meet current family living expenses. Unit trusts also would not be subject to this rule because they are treated as companies under the Income Tax Act 2007.

3.20 An exclusion could also be made for trusts where neither the settlor nor any member of the settlor’s family can be beneficiary without a Court order.

Definition of “controlled company”

3.21 A company controlled by a trust (a “controlled company”) would be defined as a company in which the trustees and their associates hold 50 percent or more of the voting interests or market value interests (if there is a market value circumstance).

3.22 The amount of net income of a controlled company that is included in trustee income would be calculated according to the proportion of voting interests in the company held by the trust using the formula below:

(trust’s voting interests/total voting interests) x company’s net income

Other aspects of attribution rule

3.23 The attribution of a company’s net income would be restricted to controlled companies only. For example, if a trust is a shareholder in a widely held company, only the dividends from that company will be included in trustee income. Also, any dividend paid by a controlled company to a trust would not be included in trustee income to prevent double counting.

3.24 The proposed attribution rule is, in substance, similar to the current rule for attributing the retained income of a controlled company to the individual shareholders for WFF purposes. Both rules would target what are similarly closely held situations. Also, in Australia, an attribution approach is used to attribute income from closely held companies and trusts to individuals to determine their Income Support payments.[8]

3.25 It should be noted that regular distributions from trusts would be separately included as family scheme income under the periodic payments rules described in paragraphs 3.87 to 3.94. However, the rules will ensure that the same income is not counted twice.

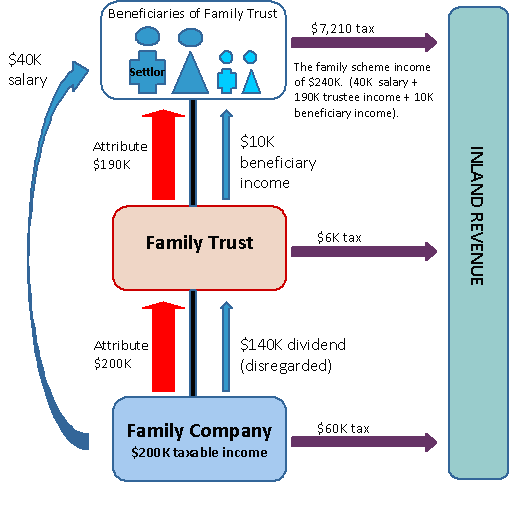

Example of how the attribution rule would work in practice

Following the previous example of Peter’s family situation, Peter is the settlor of Family Trust. Family Company is wholly owned by Family Trust. Family Company’s taxable income is $200,000 and it pays an imputed dividend of $140,000 to Family Trust.

For WFF purposes, Family Company’s taxable income of $200,000 is attributed to Family Trust. The dividend of $140,000 paid to Family Trust is disregarded for WFF purposes to avoid double counting.

Family Trust distributes $10,000 beneficiary income to Peter’s spouse. Consequently, under the proposal, trustee income of $190,000 is included in family scheme income.

Peter also receives a salary of $40,000 from Family Company. This salary has been already deducted from Family Company’s taxable income. Therefore, Peter’s $40,000 salary is included separately in family scheme income.

Peter’s family scheme income is $240,000 in total. Peter’s family would not be entitled to any WFF tax credits.

This is illustrated in the following diagram:

Multiple settlors

3.26 In some situations, more than one immediate family may be involved in a closely held trust situation. For example, there may be several individuals who are settlors of a trust and have families of their own. In these situations, attributing all of the trustee income to each individual may not be justified since not all trustee income is available to meet each family’s living expenses.

3.27 For this reason, trustee income would be attributed to multiple settlors of a trust on a proportionate basis using the formula below:

trustee income for an income year

number of settlors of the trust

3.28 This approach precludes the compliance costs associated with having to track and value the settlements of each settlor.

Alternative approach

3.29 An alternative approach would be to count only distributions of trustee income made by closely held trusts, rather than attributing all trustee income to settlors. The distributions to the beneficiaries would be included in their family scheme income. If this approach is adopted, the definition of distribution would be widely defined to include soft loans[9] and the purchase of assets from the family such as the family home and other personal assets.

3.30 However, a distribution approach could be partially circumvented by people only receiving large lump sum distributions once every few years. Although they may not qualify for WFF in the year of distribution, they could qualify in between years, while living off the lump sum distribution. This could be addressed by a rule allowing the Commissioner to look back two years and add back any lump sum distributions from the trust.

3.31 Applying the attribution rule in closely held situations is preferred at this stage because the attribution approach more accurately takes into account resources available to meet a family’s living expenses. In contrast, the alternative distribution approach captures only income actually received by the family and not income that is available to meet the family’s living expenses but is retained in the trust. Furthermore, the attribution approach avoids the problem of families recharacterising distributions of trustee income as, for example, soft loans. An additional disadvantage of the distribution approach is that it could capture distributions of capital, in particular, from a testamentary trust.

Submission points

- Are there any concerns with the proposed solution for attributing trustee income to the settlors of the trust?

- Should the distribution approach be adopted instead?

Fringe benefits received by employees

The issue

3.32 Fringe benefits are currently not included in the definition of income for social assistance purposes because they are taxed to the employer rather than included in the employee’s taxable income.

3.33 Typically, fringe benefits are non-cash items of value provided to an employee in exchange for past, current or future employment. This includes a wide range of benefits from subsidised meals to motor vehicles. Not all fringe benefits are subject to fringe benefit tax (for example, some fringe benefits provided to an employee of a charitable organisation and those received and enjoyed on the employer’s premises are excluded).

3.34 In principle all fringe benefits, whether they are subject to fringe benefit tax or not, should be counted as family scheme income if they are easily substitutable for cash or household expenditure, such as the use of a motor vehicle.

3.35 However, including all fringe benefits provided to employees would impose high compliance costs on employers and employees when applying for WFF tax credits. The value of any benefits provided would need to be attributed to each individual employee applying for WFF tax credits. That information would then have to be provided to Inland Revenue by either the employer or employee. Such an attribution of all benefits is currently not required to comply with the fringe benefits rules because of the complexity, particularly with respect to shared or low-value benefits.

Proposed solution

What fringe benefits should be included in family scheme income?

3.36 To mitigate some of these compliance costs, only those benefits which are attributable to individual employees for the purposes of the fringe benefit tax rules could be included as family scheme income. Attributable benefits are significant benefits, many of which are easily substitutable for cash.

3.37 The advantage of including only attributable fringe benefits is that this exercise already occurs as part of existing compliance with the fringe benefit tax rules. The information should be readily available to the employer to provide to the employee and/or Inland Revenue for the purposes of calculating WFF entitlements.

3.38 Under the fringe benefit tax rules, the following benefits are attributed to employees:

- motor vehicles;

- low-interest employee loans;

- subsidised transport (when the employer is in the business of transporting the public);

- contributions to sickness, accident or death funds (and funeral trusts);

- payments to insurance schemes;

- employer contributions to superannuation schemes as defined in the Income Tax Act 2007 (this excludes superannuation schemes registered under the Superannuation Schemes Act 1989 and the KiwiSaver Act 2006); and

- undefined benefits above a threshold of $2,000 per employee per annum.

3.39 Fringe benefits consisting of the provision of the private use of a motor vehicle and employee loans are attributed in all cases. The attribution of the above other benefits is required by employers if the benefit has a value to the employee of $1,000 or more in a year (except for undefined benefits which has a threshold of $2,000).[10] Employers have the option of attributing benefits below these thresholds.

3.40 Therefore benefits would only be included for WFF purposes if the employer attributes a benefit to an employee for the purposes of the fringe benefit tax rules in sections RD 47 to RD 49 of the Income Tax Act 2007.

3.41 Employers would be required to provide information on attributable fringe benefits to employees for inclusion in their application for WFF tax credits.

3.42 However, attributing fringe benefits may not always provide a consistent and equitable treatment of income for WFF purposes. Employees may receive a fringe benefit that is incidental to their work. In such situations, the value of the benefit for WFF income purposes may be greater than the economic value to the employee.[11]

3.43 As mentioned, not all benefits are subject to fringe benefit tax (for example, benefits which are enjoyed on the employer’s premises). This means even using attributable fringe benefits provided to all employees would create some inequity between employees.

3.44 This may occur if, for example, an employee is granted private use of a motor vehicle that is of greater value than they would themselves pay or that they seldom use for a private purpose. In this situation the value of the vehicle attributed to the employee is not an accurate reflection of their actual income.

3.45 On the other hand, a work-related vehicle can be used for transport to and from work without being classified as for private use and giving rise to a fringe benefit whereas a non-related work vehicle would give rise to a fringe benefit in such circumstances.[12] This creates an inequity due to the nature of the motor vehicle provided and the conditions of its use.

3.46 An example of how the value and availability of an employee’s motor vehicle could affect their WFF tax credit entitlements is provided below.

Example

Joe is employed as a regional sales manager. Joe is married and has three children under 13 years of age. Joe’s partner does not work or earn any income. Joe receives a salary of $70,000 and is provided a motor vehicle (cost price of $60,000 including GST) which is available at all times for private use.

Under the current definition of income, Joe’s situation is as follows:

| Cash salary | $70,000 |

| WFF income | $70,000 |

| WFF tax credits | $7,427 ($143 per week) |

If Joe’s attributed fringe benefits were affected by this proposal, his situation becomes:

| Cash salary | $70,000 |

|

Attributed income from fringe benefit (motor vehicle) |

$17,909 |

| WFF income | $87,909 |

| WFF tax credits | $3,846 ($74 per week) |

Under the proposal in this paper, Joe’s entitlement to WFF tax credits decreases by $3,581 for the year.

However, if the motor vehicle is a work-related vehicle and travel to and from work is necessary for, and a condition of, Joe’s employment, then travel from home to work is not treated as private use. The number of days the vehicle is available for private use would be reduced from 90 days for the quarter to 25 days. In this case, Joe’s WFF tax credits would only decrease to $6,432 ($123 per week).

Who should this proposal apply to?

3.47 Including attributable fringe benefits received by all employees may create inequity. There is a concern with the private use of motor vehicles, as illustrated in the example above. The valuation for other attributable fringe benefits is usually the market value of the goods and services provided or the actual contributions made. When a market value is readily available then the benefit to the employee is clear. There is the additional issue that not all benefits are subject to fringe benefit tax and therefore they may not be included as family scheme income.

3.48 It may therefore be more appropriate to include attributable fringe benefits as family scheme income only to the extent that the employee can clearly influence the nature of the fringe benefits they receive as part of their employment.

3.49 Under this approach, attributed fringe benefits would be included as family scheme income if the employee is also a shareholder. Although this would not capture the true income of employees in the wider sense, shareholders of closely held companies would no longer be able to reduce their income for WFF purposes by receiving fringe benefits.

3.50 It is, therefore, proposed that attribution of fringe benefits should apply only when the person applying for WFF is an employee of a company in which, together with associates, they hold 50 percent or more of the voting interests (or market value interests if a market value circumstance exists).

3.51 The reason for limiting the rule to closely held company situations is because a major shareholder is able to arrange for a substantial proportion of their remuneration to be paid as fringe benefits instead of wages. Usually, employees who do not have a controlling interest in the company have less influence over the composition of their remuneration.

3.52 Note that the attribution rule for trustee income in closely held company situations proposed in paragraphs 3.10 to 3.28 does not result in fringe benefits being included as WFF income. This is because the company obtains a deduction for expenditure on fringe benefits. A deduction reduces the net income attributed to family scheme income so the value of fringe benefits is not included. Therefore a separate rule for fringe benefits is required.

What should be the value?

3.53 The value of the fringe benefit that should be included for WFF tax credit purposes is the tax-inclusive value of the benefit. This ensures that fringe benefits are included on a before-tax basis for WFF tax credit purposes. This is consistent with the treatment of salary and wages. Under the fringe benefit rules an employer calculates the tax payable on the value of attributed benefits and for WFF tax credit purposes this amount should be added to the value of the attributed benefits to give a tax-inclusive (gross) amount.

Salary sacrifice arrangements

3.54 Employees who enter into salary sacrifice arrangements with employers also have control over the make-up of their total remuneration package. Salary sacrifice is an arrangement whereby an employee is given an explicit choice of a cash salary or a reduced cash salary plus a benefit. A typical example would be when an employee can choose between a cash salary plus a motor vehicle or a higher cash salary.

3.55 In such instances the employee can make an explicit choice between the fringe benefit and cash as they are substitutes. Such arrangements are similar to remuneration received by a shareholder/employee and should therefore also be taken into account in family scheme income. However, there are wider issues relating to the tax treatment of salary sacrifice that need to be addressed such as the ability to receive fringe benefits that are not subject to fringe benefit tax. Therefore, it is more appropriate to consider the implications of salary sacrifice for WFF tax credit purposes as part of a wider review of salary sacrifice arrangements.

Submission points

- Should only attributable fringe benefits of shareholder/employees be included in family scheme income?

- Should the fringe benefit tax rules that define and value attributable fringe benefits be used in determining family scheme income?

- Will shareholder/employees be able to estimate the tax-inclusive value of attributable fringe benefits?

Income of children

The issue

3.56 Given that WFF tax credits are provided for the support of a family with dependent children, there is an argument that the children’s income should be included in family scheme income for WFF purposes. Currently, any income earned directly by children is not counted for WFF tax credit purposes.[13] Although the parents are responsible for meeting the day-to-day household expenses, some arrangements involving children can have an effect of lowering the income of parents to increase their WFF entitlements. Parents may allocate income directly to their children through family trusts and companies or place their investments directly under their children’s names.[14] This income can then be used to meet the family’s day-to-day expenses.

Proposed solution

3.57 Not all income of children should be included as there are circumstances when reasonable earnings by children are not available for the family’s living expenses. The main concern is when there is a risk of parental income being disguised as the income of children. This income should be included in family scheme income.

Wages

3.58 In general, wages of dependent children should not be included in family scheme income of parents. Wages earned by children are generally not used to meet a family’s day-to-day expenses. Also some protections are already in place in this area. If a child is under 16 years, they are required to be in full-time education by law, and their wages from occasional part-time work are limited by this requirement. If a child is 16 years or over and they earn significant wages, they would be treated as financially independent and their parents would not qualify for WFF tax credits. “Financially independent” is defined as being in full-time employment.[15]

3.59 There is more scope for excessive wages to be paid to dependent children from a family entity (for example, a closely held company or trust). Parents could allocate income to their children circumventing the proposed rule for closely held company or trust situations.

3.60 However, including wages received by children in closely held situations only would raise equity issues. Children working for a family business would be treated differently from children working for any other business. Furthermore, anti-avoidance provisions could deter excessive wages or benefits being provided to children employed by a family business.[16]

Passive income

3.61 Passive income, such as interest and dividends received by dependent children, should be included in family scheme income. Some protection is needed to address parents placing investments directly in the children’s name or arranging for children to receive distributions from family trusts and companies. If this income were derived directly by the parents, it would be counted for WFF purposes.

3.62 However, small amounts of passive income earned by the large majority of children are unlikely to be put towards the family’s living expenses. There would be relatively significant compliance costs for parents to declare small amounts of children’s passive income. Therefore only passive income above a threshold should be included as WFF income. The intention is to exclude modest amounts of income – for example, from children’s savings accounts.

3.63 The proposed rule for passive income received by children would have the following features:

- Passive income received by a child would be included as family scheme income. The definition of “passive income” would be based on the definitions used in the former section LC 1 (relating to the low-income rebate) and section RE 2 (relating to resident passive income) in the Income Tax Act 2007. This definition of passive income would include interest, dividends, royalties, rents, a taxable Māori Authority distribution other than a retirement scheme contribution and a replacement payment under a share-lending arrangement.

- Beneficiary income received by a child would also be included as family scheme income. However, the exclusions in the minor beneficiary rule (for example, for certain testamentary trusts) should also apply for this proposed rule for children’s income.[17]

- A threshold of $1,000 would apply per child each year. This is currently the threshold that also applies in the minor beneficiary rule in the Income Tax Act 2007.

3.64 The rules for including children’s income in family scheme income would therefore be based on established principles in the Income Tax Act 2007. The minor beneficiary rule was introduced to prevent parents diverting income to children to avoid the top personal income tax rate and, instead, have such income taxed at the trustee rate. The rationale for including certain income of children in family scheme income is similar.

Submission points

- Are there any concerns with the proposed solution to include only passive income and beneficiary income of children?

- Is the threshold of $1,000 per child for passive income and beneficiary income appropriate?

Unlocked portfolio investment entities (PIEs)

The issue

3.65 Income from portfolio investment entities (PIEs) is currently not counted for WFF purposes. This exemption is appropriate for PIEs that are mainly intended to provide retirement benefits and cannot be easily accessed. However, the exemption is not appropriate for unlocked PIE investments which are readily available to meet a family’s living expenses. Unlocked PIEs are where the funds are not sufficiently locked-in until a person’s retirement. Examples include cash PIEs, which are akin to on-call bank accounts, PIEs that are unregistered superannuation schemes and listed PIEs.

Proposed solution

3.66 Income from unlocked PIEs would be included for WFF purposes. This income is analogous to direct income from investments such as interest earned on bank accounts that is currently included for WFF purposes. Specifically, attributed PIE income, as defined in the income tax legislation, earned from unlocked PIEs would be included in family scheme income.

3.67 Unlocked PIEs would be defined as all PIEs except superannuation schemes that are registered with the Government Actuary. Registered superannuation schemes must be established primarily for the purpose of retirement benefits. Therefore, if a scheme can be readily accessed to meet day-to-day expenses (for example, cash PIEs and listed PIEs), it should not be eligible to be registered with the Government Actuary.

Submission points

- Are there any concerns with the proposal to include income from unlocked PIEs in family scheme income?

- Is a superannuation scheme’s registration with the Government Actuary an appropriate test for not including PIE income in the proposed family scheme income?

Income of non-resident spouses[18]

The issue

3.68 Eligibility for WFF tax credits is based on household income. In most circumstances, the carers of the children are resident in New Zealand and their combined New Zealand and overseas income is taken into account.

3.69 However, when one spouse resides overseas and the other spouse lives in New Zealand with the children – often receiving taxpayer-funded benefits such as education – the offshore income of the non-resident spouse may not be included in family scheme income. This is despite the offshore income being available and often used to support the children resident in New Zealand. Not including the non-resident spouse’s worldwide income increases the family’s entitlement to WFF tax credits.

3.70 Note that if the parents of the children are separated, any maintenance payments made by the non-resident parent to the resident parent are already included as WFF income.[19]

Proposed solution

3.71 Given that WFF is provided on the basis of household income, the worldwide income of both spouses should be included in family scheme income. Under this approach, the non-resident spouse’s offshore income would be included. This would ensure equitable treatment with families where both spouses live in New Zealand. Counting the worldwide income of both spouses also better reflects the economic income of these families.

3.72 Under this approach, the non-resident spouse would be required to provide evidence of their income from overseas.

3.73 An alternative approach would be to include only the remittances from the non-resident spouse in family scheme income. Remittances would include contributions towards a child’s education, mortgage payments and other household expenses. Identifying and measuring remittances may present some compliance and administrative challenges.

3.74 Furthermore, this approach takes into account only income received by the resident spouse and does not reflect the income actually available to the family. It is also less equitable relative to the treatment of resident families.

3.75 On balance, the worldwide income approach should be relatively simple to administer especially if proof of income is able to be obtained.

Submission points

- Are there any concerns with the proposal to include the worldwide income of a non-resident spouse in family scheme income?

- Are there any compliance issues with this approach?

- Should only remittances from the non-resident spouse be included instead?

Exempt income

The issue

3.76 Currently, some income that is exempt from tax, such as maintenance payments, is included in family scheme income on the basis that the income is available to meet the family’s day-to-day living expenses which the WFF scheme is designed to assist with. However, certain types of exempt income are not included even though they are available to meet the family’s living expenses.

Proposed solution

Exempt income in the nature of salary or wages

3.77 Some salary or wages are exempt income and not counted as taxable income or family scheme income. An example would be salaries received by employees of international organisations such as the United Nations or the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Note that at least one spouse, as well as any children, must be resident in New Zealand to claim WFF tax credits.

Bonus bonds and similar “save and win” bank accounts[20]

3.78 Bonus bonds prizes and prizes in “save and win” bank accounts are exempt income. They are similar in nature to other investments where the investor’s capital is low risk and returns on other investments are included in family scheme income. A key point of difference is that the probability of a return and the rate of return are both uncertain. In this they are similar to prizes from gaming (such as lotteries), which are also exempt from tax. However, they differ from gaming in that there is a reasonable expectation in gaming that the amount paid or bet will be lost.

3.79 Any return on bonus bonds or “save and win” bank accounts is economic income to the investor. Accordingly, bonus bond prizes and prizes in “save and win” bank accounts could be included in family scheme income.

3.80 Payments under life insurance policies entered into in New Zealand are exempt income. It is not currently proposed to include such payments in family scheme income other than annuities. However, this may be reviewed if it becomes evident that life insurance policies are being marketed and used to inflate social assistance entitlements.

Submission points

- Should salary and wages from international organisations that are exempt income be included in family scheme income?

- Should bonus bonds prizes and prizes in “save and win” bank accounts be included in family scheme income?

- Are there other types of exempt income that should be included in family scheme income?

Main income equalisation scheme deposits

The issue

3.81 The main income equalisation scheme is intended to allow persons carrying on an agricultural, fishing or forestry business to smooth their incomes to address large fluctuations of income over several years. A deposit to a main income equalisation account is allowed as a deduction for income tax purposes.

3.82 By reducing their taxable income, deposits in these schemes also reduce their income for WFF purposes. This is income that was available to meet the family’s living expenses. Deposits into these accounts should not be recognised for the purposes of a family’s entitlement to social assistance such as WFF tax credits and student allowances.

Proposed solution

3.83 Deposits entered in a person’s main income equalisation account should be included in family scheme income. To prevent double counting, refunds (excluding interest) from main income equalisation accounts would not be included in family scheme income. Deposits in adverse event income equalisation schemes would not be covered by this proposal.

3.84 The proposed solution is consistent with the treatment before the 2002–03 income year when a deduction was not allowed for family assistance tax credit purposes for deposits to main income equalisation accounts.

Submission point

Should deposits to a main income equalisation scheme account be included in family scheme income?

Periodic payments

The issue

3.85 Individuals may receive regular payments such as gifts, soft loans[21] from family members and trusts, or distributions of trustee income that are available to meet the family’s living expenses and are not captured by the income types mentioned earlier. Such periodic payments that are not subject to income tax in the hands of the individuals receiving them are not included in family scheme income.

3.86 Section MB 1(6) of the Income Tax Act 2007 states that the Commissioner must have regard to income from all sources known to the Commissioner in calculating family scheme income. There is some uncertainty over what this provision actually captures. Including other periodic payments in the definition would reinforce this section and provide more certainty through a clearer rule.

Proposed solution

3.87 Periodic payments that are used to meet the family’s living expenses should be included in family scheme income.

3.88 A definition similar to that used for welfare payments in the Social Security Act 1964 could be adopted for WFF purposes. However, any definition needs to be properly targeted and not include economic income that is not reasonably available to meet family needs, or which has high compliance costs to measure and report. Family scheme income would be defined to include any periodic cash payments received and used by the person for income-related purposes.

3.89 This definition would include various types of regular payments received by individuals that are used to meet day-to-day living expenses. It would include any regular cash gifts, payment of expenses or distributions received from trusts.

3.90 Regular or periodic would mean an expectation that the payment would be more than a one-off payment and could include annual payments. A regular payment would be considered to be used for an income-related purpose if it is:

- replacing lost or diminished income; or

- maintaining the applicant or their family; or

- purchasing goods or services (commonly paid for from income) for the applicant or their family; or

- enabling the applicant to make payments that they are liable to make and that are commonly made from income.

3.91 Examples include a person receiving payments from an income-related insurance policy, other than life insurance, to cover loss of employment income, or receiving payments from a family member to supplement income. Other examples include payments received to meet essential living costs such as rent, servicing a mortgage, food, power and clothing or to pay hire purchase accounts, insurance payments or fines. It also includes when a person’s regular expenses are directly paid for by a third person, such as paying utility bills directly.

3.92 Any one-off capital payments would be excluded, such as payment from the sale of a house. In addition, the following types of income or payments would be excluded:

- Any payments that have specific purposes other than income-related purposes such as funeral grants, educational scholarships, lump sum ACC compensation payments, non-taxable payments under the Social Security Act 1964, charitable distributions or compensation-type payments.

- Any student loan payments under the Student Loan Scheme Act 1992, including the living costs component of student loans.

- Any specified item or amount of income, or income from a specified source, that is declared not to be income for the purposes of the Social Security Act 1964 by regulations made under section 132 of that Act, such as payments to victims of crime.

- Periodic payments received from the repayment of loan principal or when the recipient of the sale of an asset is paid in instalments.

- Payments that are already included under another family scheme income provision, to avoid double counting.

3.93 In other definitions of income, such as the definition used in the community services card rules, there are exclusions for 50 percent of private pensions received and 50 percent of annuities. The rationale is that some portion of these payments is the return of the original capital investment rather than income, when the capital is returned on a periodic basis rather than as a lump sum. A question arises whether a similar exclusion should apply here.

3.94 A question also arises whether to include the regular forgiveness of interest or the principal on a loan, particularly on soft loans between family members. The rationale is that by forgiving interest or debt that would otherwise be paid, usually out of income, it increases the amount of income the family has to use for other purposes.

Submission points

- Are there any concerns on the proposed solution to include periodic cash payments in family scheme income?

- Are there any other types of income or payments that should be excluded from the above definition, such as 50 percent of annuity payments or private pensions?

- Should periodic forgiveness of interest or the principal on a loan be included in the definition of “periodic payments”?

7Note that the example takes into account WFF tax credit entitlements only. The WFF tax credit entitlements are calculated on the assumption that all children are under 13 years old and the figures are rounded. The tax rates and the WFF tax credit entitlements are based on the rates before 1 October 2010.

8Income Support payments in Australia are equivalent to welfare payments paid under the Social Security Act 1964 in New Zealand.

9Related party loans where the interest or repayment is regularly deferred or written off.

10Sections RD 47, 48 and 49 of the Income Tax Act 2007.

11The calculation of the value of a motor vehicle as a fringe benefit does include some discount to reflect the lower economic value to the employee. However, this discount is a benchmark only and therefore may over- or under-estimate the actual value to the employee. See Report of the Task Force on Tax Reform, Wellington, 1982, Chapter 6, Appendix A (McCaw Committee).

12See section CX 38 of the Income Tax Act 2007 on the meaning of a work-related vehicle.

13This consistent with the definition of “income for benefit purposes” under the Social Security Act 1964.

14Some of these arrangements may be subject to anti-avoidance provisions in the Income Tax Act 2007.

15See the definition of “financially independent” in section YA 1 of the Income Tax Act 2007.

16Sections GB 23, GB 24 and GB 44 of the Income Tax Act 2007.

17See section HC 35 of the Income Tax Act 2007.

18For the purpose of this paper, a non-resident spouse means a person who is married to or in a civil union or de facto relationship with a person claiming WFF tax credits.

19Under section CW 32 of the Income Tax Act 2007, maintenance payments are referred to as a payment in the nature of maintenance out of money belonging to a person’s spouse, civil union partner or de facto partner, or former spouse, former civil union partner or former de facto partner.

20These are accounts where the money deposited provides opportunity to win prizes, and where the level of interest earned is nil or significantly less than standard accounts.

21Soft loans are loans with a discounted interest rate and/or lenient options for repayment. They are usually non-commercial loans between family members or family controlled entities.