Chapter 5 - Taking both parents' income into account

This chapter discusses the merits of taking both parents’ income into account for the purposes of determining child support payments, and of providing each parent with a set living allowance as a deduction from their income.

Submissions are invited on these points as well as on whether, in the absence of a recognised shared care arrangement, there should continue to be a minimum child support payment.

5.1 Taking into account the income of both parents in determining levels of child support payments may better reflect the realities of modern-day parenting and parents’ relative abilities to contribute towards the expenditure for raising their children. This is consistent with providing a better recognition of shared care and applying corresponding costs as discussed earlier.

Background

5.2 The standard child support formula takes into account the income of the paying parent only. Social and demographic changes in society since the introduction of the scheme mean, however, that it is more likely that a receiving parent is now also participating in the workforce.

5.3 Labour-force participation rates for women were at a record high of 62.5 percent in the year ending March 2009 compared with 54.3 percent for the same period in 1992.[30] Over the same period there was little change in the male labour-force participation rate. Women were more likely to be working part-time, with female workforce participation tending to increase as children grow older. It is therefore clear that an increasing majority of parents now depend on two incomes to support their children.

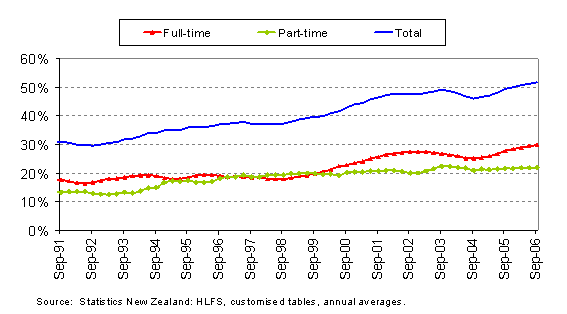

5.4 The percentage of sole mothers participating in paid employment has correspondingly increased since 1992, as shown in Figure 5.[31]

Figure 5: Percentage of sole mothers employed part- and full-time 1991–2006

5.5 In view of the evidence, it seems reasonable to consider both parents’ financial capacities to support their children. This is consistent with trying to replicate, as far as possible, the financial arrangements that existed in providing for children before their parents began living apart (notwithstanding that separation may cause a decline in living standards).

5.6 Although both parents’ incomes can be taken into account under the current scheme where shared care exists by each parent cross-applying for child support, which involves the respective liabilities being offset to produce a net amount for one parent to pay, cross-application can be impractical for the parties involved and can also be administratively cumbersome. A more direct method may be needed.

Income-shares approach

5.7 The essential feature of a child support scheme that directly reflects both parents’ incomes is that the expenditure for raising children are worked out based on the parents’ combined income, with those costs distributed between parents in accordance with their respective shares of that combined income and their level of care of the child. The Australian scheme discussed in earlier chapters adopts this “income-shares” approach as do a number of other jurisdictions, including Norway, Sweden and several U.S. states.

5.8 The Government seeks your feedback on whether this combined cost and income-shares approach should be adopted in New Zealand.

Advantages and disadvantages of an income-shares approach

5.9 The main advantages of an income-shares approach are:

- It is more transparent. It provides an estimate of how much is being contributed by each parent towards the support of their child.

- It better reflects parents’ relative abilities to financially contribute towards the expenditure for their children and parallels likely expenditure by those parents as if they were in a two-parent household where both parents have income.

- It makes processes around changes of financial circumstances clearer and simpler. If there is a reduction in the income of either parent, this can be automatically reflected in the contribution calculation, potentially removing the need for an administrative review.

5.10 Possible disadvantages of the income-shares approach are:

- If the receiving parent’s income varies significantly – for example, to accommodate the needs of children, there is potential to increase conflict between parents as the paying parent’s child support contribution would also vary.

- Some receiving parents could be discouraged from participating in the workforce because a portion of every dollar they earned over the self-support amount would be “lost” through a decrease in the child support they received. On the other hand, there may be a greater incentive for paying parents to earn higher incomes if they were paying less in child support as a result of both incomes being taken into account.

- The approach could make the level of payments less secure as a change in either parent’s income may well result in a change in child support payable or receivable.

5.11 These arguments, however, need to be balanced against the reality that changes in either parent’s work patterns do impact on their children and would do so if the parents were living together. Ideally, the formula should reflect this reality in which case the advantages of the income-shares approach would seem to outweigh the possible disadvantages.

Changing the definition of “income”

5.12 Ideally how “income” is defined for child support purposes should align with how it is defined for tax credit purposes; that is, it should generally continue to be taxable income. Budget 2010 made an important change to the way that income is defined for tax credit purposes. From 1 April 2011, investment losses, including losses from rental properties, will be added back so that these losses cannot be used to reduce income when assessing eligibility for Working for Families Tax Credits. The Government is considering making a similar change for child support purposes on the basis that this would better reflect the real income that families would normally have available to them.

5.13 Budget 2010 also signalled that the Government would be introducing other measures in relation to Working for Families Tax Credits, including ensuring trust income is counted as part of a family’s total income. These changes could be considered in the child support context too. In the meantime, the use of trusts can currently be taken into account under the administrative review process, including Commissioner initiated reviews.

5.14 Also relevant to this consideration is that means-tested benefits, such as the domestic purposes benefit and the unemployment benefit, are taxable income[32] but child support receipts and tax credits, such as the family tax credit, are not.

Living allowance

5.15 New Zealand currently deducts from a paying parent’s income an amount considered necessary to cover the parent’s living expenses. Australia has a similar adjustment with two key differences.

5.16 The first difference is that in Australia there is just one living allowance amount, set at one-third of the average earnings for a male employee. It does not vary even if, for example, there are children from another relationship. Children from a current relationship are instead factored into the calculations in a similar manner to children who receive child support by applying the cost percentage for the relevant child support income band. This amount is then deducted from the relevant parent’s income for child support purposes.

5.17 The second difference is that both parents qualify for the living allowance adjustment given that their combined incomes are used as the basis for calculating contributions.

5.18 The Government is considering this approach for New Zealand. Given that annual average earnings are $48,162 in New Zealand, one-third of this would mean a living allowance of $16,054, which is above the current living allowance for a single parent with no dependents ($14,158). Under this approach, both parents’ taxable incomes would be reduced by this amount. An example of what this would mean for parents with dependent children is provided in the next chapter.

Minimum payment

5.19 The living allowance is of relatively more benefit to low-income earners. This means that in some cases parents with low incomes pay very little towards the expenditure for their children – perhaps less than if they were in a two-parent family situation.

5.20 In developing the suggestions in this discussion document, consideration was given to whether the minimum payment should be set closer to the basic expenditure for raising a child, which would result in an amount of between $2,000 and $3,000. However, as shown in Figure 4 in chapter 3, for low-income earners the tax benefits foregone when they have little care of their children would essentially match this amount. A low minimum payment (currently $815) would still seem to be justified.

5.21 If lower levels of regular shared care were recognised, this minimum payment could be waived on the basis that the costs incurred from regular care would be at least equivalent to the minimum payment.

30 Statistics New Zealand – Household Labour Force Survey

31 Ministry of Social Development, June 2007 – “The 2002 Domestic Purposes and Widows’ Benefit Reform: Evaluation report”.