Chapter 5 - Further Options for Managing the Goverment's Revenue Risk

5.1 A crucial element of the credit-invoice tax framework is the GST-registered person’s ability to obtain refunds when input tax deductions exceed the output tax charged in a given taxable period. Inland Revenue has an obligation to be vigilant in the payment of GST refunds, given the revenue risks that would otherwise arise.

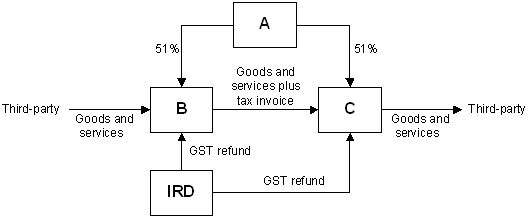

5.2 An example of these revenue risks includes the use of “phoenix” entities (see Figure 1) to create input tax and “carousel fraud”, which has been a particular problem for governments in the European Union.

5.3 This chapter outlines, for comment, possible solutions (in addition to the domestic reverse charge discussed in paragraph 4) to address the risks such as:

- treating legally separate entities as a single economic entity in specific situations;

- using caveats to improve Inland Revenue’s information-gathering for certain types of transactions; and

- increasing the time available to Inland Revenue to process refunds.

Threats to business-to-business neutrality

“Phoenix” entities

5.4 “Phoenix” entities can be problematic for the operation of GST because the purchase of assets from the failed entity by the “re-born” entity can give rise to an input tax entitlement without the corresponding payment of GST. This asymmetrical treatment is a cost to the government, but when it occurs because of a genuine business failure it is a recognised trade-off for the wider benefits that come from the comprehensive application of GST. On the other hand, if the entity becomes insolvent as a result of the conscious actions of its owners and/or the entity’s assets are transferred to an associated entity, the result may be inconsistent with the objective of providing business neutrality.

5.5 The government has recently responded to some of the general problems created by phoenix entities by changing the laws governing the appointment of liquidators and introducing a framework of “voluntary administration” to assist creditors of financially troubled companies.[35] Nevertheless, specific measures may be needed to deal with the GST concerns discussed in this paper.

Figure 1: Illustration of a Possible "Pheonix" Arrangement

Notes:

- Company B claims an input tax deduction in the usual manner in connection with its purchases from third parties and supplies goods and services to Company C.

- Company C does not immediately pay Company B – who accounts for GST using the payments basis. Company C claims an input tax deduction on the basis of the tax invoice provided by Company B.

- Person A decides to wind up Company B leaving an unpaid tax debt.

- The transaction between companies B and C therefore creates an input tax deduction which is not met by a corresponding payment of GST from B.

“Carousel fraud”

5.6 Internationally, there have been high-profile instances where government revenues have been affected by fraud and aggressive structures designed to exploit the refunds that can arise from input tax deductions.[36] These arrangements, commonly referred to as “carousel fraud”, are deliberately designed not to be neutral.

5.7 As reported in the European Union, carousel fraud works like this:

- An entity (entity A) based in, say, Germany supplies goods to entity B, which is based in the United Kingdom. Entity A zero-rates the supply as it is an export.

- As the supply is an intra-community transaction between European Union businesses, entity B is required to self-assess VAT using the relevant rate of VAT for that member state. Entity B would generally recognise an input tax deduction for self-assessed VAT in the same return period.

- Entity B on-sells the goods to entity C, which is based in the United Kingdom. Entity B charges VAT on the transaction and ceases operation as soon as the goods are sold. Entity B retains the VAT charged and does not file a return.

- Entity C claims a deduction for the VAT charged by entity B and exports the goods to entity A. The supply is zero-rated.

- These steps are then repeated.

5.8 Technically, it is possible for carousel fraud to occur in New Zealand. While this has not been a significant concern to date, the possibility that it could occur should, in our view, be taken into account in developing any base protection measures.

Current methods of managing GST risk

5.9 Aside from the general tax-neutral framework provided by the GST system, an important tool in managing GST risk is the Crown’s status as a preferential creditor in collecting tax payable that is unpaid at the time of a bankruptcy, liquidation or receivership. “Tax payable” is the net difference between GST charged and input tax deductions assessed by a GST-registered person for a taxable period. The Crown’s preference reflects that GST, while not held on trust like PAYE or other withholding payments, is charged by businesses on the goods and services they supply to their customers. GST charged can be used by GST-registered persons in their day-to-day cash management. The use of GST monies in this way means that the government does not have the benefit of the tax at the time it is charged.

5.10 The GST Act contains provisions that allow for refunds arising from excess input tax deductions to be set off against other outstanding tax debts owed by the GST-registered person. These rules are designed to apply before a GST-registered person encounters financial difficulties and is an efficient means of collecting the debts.

5.11 However, Inland Revenue’s current powers to enforce the payment of tax are premised on the entity having sufficient financial assets on which to make payment. In the case of phoenix and carousel fraud, the purpose is to leave the entities involved without any financial assets that could be subject to the Crown’s preference or the Inland Revenue’s powers to set off.

5.12 As the problems created by such fraud stem from the operation of the GST Act, tax-specific changes are needed in addition to the previously discussed changes to commercial law.

Options being considered

5.13 The domestic reverse charge discussed in chapter 4 will partially address our concerns with phoenix and carousel fraud but we have outlined in the remainder of this chapter some further possible measures. We acknowledge that legislative solutions for addressing fraud have their inherent limitations which can only be dealt with administratively.

Enforcing business-to-business neutrality

5.14 When outstanding GST debts have been deliberately created to provide corresponding input tax deduction entitlements to closely associated entities, one option would be to treat such associated GST-registered suppliers and recipients as the same economic entity. That could be achieved by widening the set-off powers available to Inland Revenue for associated persons’ transactions.

5.15 The intention is to ensure that the net effect of transactions between close associates is neutral so that they do not create a GST liability or corresponding input tax entitlement, in much the same way that transactions between a group of companies should not result in GST consequences – change-in-use adjustments being the exception. We would not suggest, however, that close associates be made liable for each other’s tax debts or that Inland Revenue’s priority in the event that a supplier becomes insolvent be advanced.

5.16 Widening the current set-off powers would include:

- Making a GST-registered company liable for GST if it acquires goods or services from an associated company that is unable to meet its tax liability. The supplier and the recipient would be treated as the same economic entity, and the input tax deduction claimed in respect of the transaction between the associated companies would be reversed.

- Making an associated person (not a company) – for example a GST-registered trust[37] – liable for GST if it acquires goods and services from a GST-registered settlor that is unable to meet its GST obligations. The settlor and the trust would be treated as the same economic entity, and the input tax deduction claimed be similarly reversed.

5.17 In these situations, the set-off power would be specific to transactions between associated persons in which there had not been a genuine economic exchange and/or when Inland Revenue is the principal creditor. When the input tax deduction claimed by the recipient was reversed, a corresponding adjustment would be made to the supplier’s GST liability to ensure that the transaction between the two parties was neutral.

5.18 To appropriately target this possible measure, a narrower definition of “associated persons” that focuses on entities under the control of the others, could be used. The suggested definition of “associated persons” that applies to land sales in the Income Tax Act 2007 would be a possibility.[38] We are considering an exclusion to the measure of widely held companies.

Specific points for consultation – enforcing business-to-business neutrality

- Do you agree with this option?

- What are the likely costs and risks with this option?

Power to impose caveats

5.19 Inland Revenue relies on the information collected from GST returns in determining its audit strategies. Much of the information contained in the return is aggregated and does not give Inland Revenue an insight into when certain types of property transactions are undertaken.

5.20 If Inland Revenue were given earlier notice of a property transaction it would be possible to detect transactions that might be viewed as detrimental to the GST base at a much earlier stage.

5.21 The intention of using caveats would not be to enforce the collection of GST, but to provide Inland Revenue with information that a transaction is likely to occur and that output tax is payable. Inland Revenue would have a discretion to lodge a caveat and would consider its application if the taxpayer had been engaged in activities that posed a risk to the integrity of the GST base.

5.22 The use of caveats could take a range of forms. For example, a caveat could be a notice that Inland Revenue lodges on the land title against the name of certain owner of land when that person acquires the land and claims a deduction either as input tax or as a change-in-use adjustment. The notice will ensure that Inland Revenue is informed when the land is sold. Subsequent to the sale, the notice would be removed automatically without the owner of the land having to contact Inland Revenue.

5.23 Alternatively, a caveat could take the strict legal form of being a restriction against dealing in land. Such caveats lodged by Inland Revenue would be removed once the owner had given Inland Revenue notice of an impending sale of property. Having received notice, Inland Revenue would direct the Land Registrar to remove the caveat, and the supplier would be able to proceed with the sale.

5.24 Since this option could otherwise result in significant compliance costs for taxpayers we have, as mentioned earlier, limited its scope. Limiting the scope of the option does, however, have the following disadvantages:

- Knowledge that the GST-registered person poses a compliance risk: Inland Revenue may not always have the necessary information to make a reasonable decision about whether a particular GST-registered person poses a risk to the GST base.

- Impact on the freedom to contract: Lending institutions may be reluctant to provide finance for transactions involving land subject to a caveat as they would know that the vendor may be a party to activities that could be the subject of a dispute between the GST-registered person and Inland Revenue.

Specific points for consultation – power to impose caveats

- Do you agree with this option?

- Would it be preferable to use a caveat in the form of a notice or a caveat against dealing in land as a mechanism for Inland Revenue to be notified of a sale?

- Do you agree that the proposal should only to transactions by those persons who are likely to pose a risk to the GST base?

- What modifications would you make to the suggested changes?

- What commercial implications would the proposal have?

Extending the timeframe for the release of refunds

5.25 When the calculation of tax payable results in a refund of GST – that is, when input tax deductions exceed output tax – Inland Revenue is required to pay that refund within 15 working days from the day following Inland Revenue’s receipt of the relevant return.[39] The GST-registered person must be notified within 15 working days if Inland Revenue intends to investigate the return and withhold payment. Inland Revenue is not precluded from investigating a return after the 15-working day period – subject to the four-year time bar.[40]

5.26 A working-day rule is used as it overcomes problems associated with public holidays that can occur using a test that is generally referenced to calendar days.

5.27 Imposing a statutory timeframe for the payment of refunds is common international practice, with the average timeframe being 30 calendar days.[41] Longer periods are also not uncommon.[42] These timeframes are important as they give GST-registered persons the confidence that returns will be processed promptly.

5.28 Following the Seahunter cases[43] notice must be received by the GST-registered person within 15 working days. Inland Revenue’s policy is therefore that notices informing GST-registered persons that it is not satisfied with a return must be issued before the end of 10 working days from the date the relevant return is received. This means Inland Revenue now has less time than originally intended to be satisfied about the correctness of any GST return.

5.29 Timeframes that are too tight may provide Inland Revenue with insufficient time to respond to transactions that could affect the integrity of the tax base.

5.30 Given the need to ensure that notice is received by GST-registered persons in the statutory period, extending the period to 20 working days may be appropriate. This would allow Inland Revenue more time to investigate and to be satisfied with the payment of refunds in order to meet its tax administration obligations. Twenty working days is also broadly consistent with international norms.

5.31 We recognise that this approach could be perceived as having an effect on the carrying cost of GST for exporters. Any extension to the timeframe determining when refunds are released should not, however, affect the processing of the vast majority of GST-returns and should not preclude Inland Revenue from continuing to enhance its processes and systems to allow the earlier release of refunds. Current response periods, particularly those applicable to exporters, should be improved over time. On the other hand, GST-registered persons that have a documented history of non-compliance (including significant outstanding debt) are likely to experience delays if Inland Revenue considers a GST-return warrants greater scrutiny.

Specific point for consultation

What concerns would you have if Inland Revenue had 20 working days to notify that it intends to investigate a GST return and withhold payment and applied this in limited cases where there are possible tax base risks?

35 See Part 15A of the Companies Act 1993.

36 Ibid footnote 6. See also The serious research gap on VAT/GST: A New Zealand perspective after 20 years of GST, International VAT monitor, September/October 2007. Carousel fraud reportedly cost the United Kingdom an estimated £3 billion in 2005 to 2006.

37 The term “trust” is used as a short-hand expression to describe the trustees of the trust.

38 See the officials’ issues paper Reforming the definition of associated persons, Policy Advice Division and the Treasury, March 2007.

39 It is at the Commissioner’s discretion whether refunds may be used to offset other tax debts.

40 See section 108A of the Tax Administration Act 1994.

41 VAT refunds: A review of country experience, International Monetary Fund WP/05/218, November 2005, G Harrison and R Krelove.

42 For example, the French value added tax system provides a 90-day timeframe. An administrative performance standard that reduces the time to 30 days applies.

43 See Seahunter Fishing Limited v Commissioner of Inland Revenue (2001) 20 NZTC 17,206 and Commissioner of Inland Revenue v Seahunter Fishing Limited (2002) 20 NZTC 17,478.