Chapter 5 - Hybrid financial instruments

- Recommendation 2

- Recommendation 1

- Particular tax status of counterparty not relevant

- Differences in valuation of payments not relevant

- Timing differences

- Taxation under other countries’ CFC rules

- Application of rule to transfers of assets

- Regulatory capital

- Other exclusions

- Application to New Zealand

5.1 This chapter discusses and asks for submissions on, various aspects of implementing the first two recommendations in the OECD’s Final Report. It first considers changes to existing domestic rules (which relate to Recommendation 2), and then considers issues relating to the linking rules in Recommendation 1.

Recommendation 2

5.2 New Zealand already denies a dividend exemption for deductible and fixed-rate dividends (section CW 9(2)(b) and (c)). Indeed, the definition of a deductible foreign equity distribution contains a simple imported mismatch rule. While this rule seems in general satisfactory, there are two situations referred to in the Final Report which New Zealand law does not deal with.

Dividends giving rise to a tax credit in the payer jurisdiction

5.3 First, current New Zealand law does not deal with foreign tax systems that use tax credits triggered by dividend payments to effectively refund corporate tax. This is considered in Example 1.11 of the Final Report. Such a regime has the same effect as a dividend deduction,[42] and it is proposed that section CW 9(2)(c) be expanded to deny exemption for a dividend which gives rise to tax relief equivalent to a deduction in the payer jurisdiction.

Denial of imputation credits

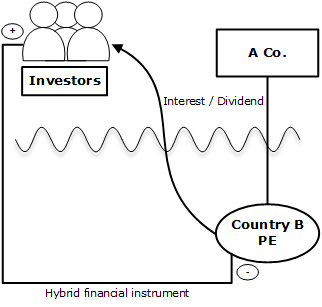

5.4 Secondly, there is no provision denying the benefit of an imputation credit to a dividend on a hybrid financial instrument. Example 2.1 in the Final Report (reproduced below as Figure 5.1) is an example of a deductible dividend with an imputation credit attached. The dividend is deductible in Country B because the instrument is treated as debt and funds the assets of the Country B branch. In Country A the dividend is taxed as a dividend and imputation credits are required to be attached to it by A Co, representing payments of corporate income tax to Country A. A number of Australian banks have entered into these types of transactions, in some cases using debt raised by their New Zealand branches, that is, New Zealand is Country B.

Figure 5.1: Application of Recommendation 2.1 to imputed dividends[43]

5.5 The Example states that under Recommendation 2.1 Country A should deny the imputation credit, because it is attached to income that has not borne tax in either state. It is true that the attachment of the credit to earnings which have not borne Country A tax may mean that A Co has retained earnings from its domestic activities which it is unable to distribute on a tax paid basis. In that sense the attachment of an imputation credit to a payment is less harmful than the payment being entirely exempt. However, in many cases the distribution of the untaxed earnings can be postponed indefinitely, so there is no practical distinction between exemption and full imputation.

5.6 Example 2.1 would not apply to a hybrid instrument issued by the foreign branch of a New Zealand company because New Zealand would tax the branch income. However, there seems no reason not to amend legislation to deny the use of imputation credits to reduce tax on a dividend which is deductible to the payer.

5.7 In relation to Recommendation 2.2, New Zealand has a general rule limiting the ability to claim a credit for foreign tax to the amount of New Zealand tax chargeable on the net income that has been subject to the foreign tax. To ensure that this provision is more closely aligned with Recommendation 2.2, it is proposed that the definition of a “segment” of foreign source income be defined so that any payment of a dividend on a share subject to a hybrid transfer is treated as a separate segment of foreign source income.

Submission point 5A

Submissions are sought on the proposed approaches to implement Recommendation 2 where necessary.

Recommendation 1

General

5.8 The hybrid financial instrument rule in the OECD’s Recommendation 1 applies to payments under a financial instrument that can be expected to result in a hybrid mismatch (that is, a D/NI result). A financial instrument can be either a debt or an equity instrument. For this purpose, an equity instrument would include any form of ownership interest in an entity which is not treated as fiscally transparent.

5.9 A simple example of a hybrid financial instrument is given in Figure 2.1 in Chapter 2.

5.10 A D/NI result arises when a payment is deductible to the payer, to the extent that that payment is to a person in a country where the payment would not be fully taxed within a reasonable period of time as ordinary income to a taxpayer of ordinary status, and a reason for that non-taxation is the terms of the instrument. Imposition of withholding tax on the payment by the payer country is not full taxation as ordinary income. D/NI outcomes can arise due to inconsistent characterisation of the financial instrument, or when the payer is entitled to a deduction before the payee has to include an amount in income (typically because the payer is on an accrual basis but the payee is on a cash basis).

5.11 The primary rule is for the payer country to neutralise the mismatch by denying the deduction. The payer country is any country where the payer is a taxpayer. It does not require the payer to be resident, and a payer can have more than one payer country. If the payer country does not deny the deduction, under the secondary rule the payee country should include the payment in the payee’s income. The payee country is any country where the payee is a taxpayer.

Rule only applies to financial instruments under domestic law

5.12 Subject to two exceptions (considered below), countries only need to apply this rule to payments under financial instruments as characterised under their own domestic law. So, for example, a cross-border lease payment by a New Zealand-resident under a lease that is not a financial arrangement would not be subject to disallowance under this rule, even if the lessor country treats the lease payment as partially a return of principal under a finance lease.[44] The definition of a financial instrument is considered in Chapter 12.

Rule only applies to payments

5.13 This rule only applies to payments between related parties (broadly, 25 percent or more common ownership) or structured arrangements. These definitions are discussed in Chapter 12.

5.14 The rule does not apply to deductions which are not for payments. Thus it does not apply to deemed deductions on an interest-free loan, but it does apply to deductions which arise from bifurcating an interest-free loan between debt and equity (Final Report, Examples 1.14 and 1.16). So, the deductions claimed by the taxpayer in Alesco would be disallowed by the primary rule in New Zealand, and if New Zealand did not have hybrid rules, be taxable in Australia under the defensive rule. They would not be affected by Recommendation 2, because Australia did not recognise the optional convertible note as giving rise to a dividend. The rule also does not apply to a bad debt deduction, which is attributable to a non-payment, rather than a payment – see Final Report, Example 1.20.

Practical considerations

5.15 This rule would mean that any person claiming a deduction for New Zealand tax purposes under a cross-border financial arrangement needs to consider, before claiming the deduction, whether:

- the deduction arises as a result of a payment that (assuming no change in the parties to the arrangement) is or will be made to a related person (applying a 25% threshold, as discussed below) or pursuant to a structured arrangement; and (if the answer to the first question is yes)

- whether under the laws of the country of the payee, the payment would be taxed as ordinary income in the hands of a taxpayer of ordinary status within a reasonable period of time. If it would not, then no deduction can be claimed.

5.16 Also, any person entitled to receive a payment under a cross-border financial instrument will need to consider, if that payment is not fully taxable (including where it is taxable but carries a credit, other than for foreign withholding tax), whether:

- the payment is from a related person or pursuant to a structured arrangement; and (if the answer to the first question is yes)

- whether under the laws of the country of the payer, the payment is deductible to a taxpayer of ordinary status. If it is, then the payment is taxable in the year of the deduction.

Particular tax status of counterparty not relevant

5.17 Only hybrid mismatches that arise as a result of the terms of an instrument are relevant. For example, if a New Zealand borrower pays interest to a related party who is tax-exempt, there will be no hybrid mismatch if the related party would have been taxable on the interest were it not tax-exempt. However, there will be a hybrid mismatch if the related party would not have been taxable on the interest if it were not tax-exempt (Final Report, Example 1.5).

5.18 Another issue is the relevance of deduction or inclusion that arises only because a payer or payee holds an instrument on revenue account. Generally the principles expressed above mean that such deductions or inclusions are ignored for purposes of this rule. For example, suppose a purchaser on revenue account is entitled to a deduction for the cost of acquiring a financial instrument whereas the vendor if on capital account does not include the sale price in its income. That mismatch does not mean that the hybrid financial instrument rule applies to the payment (see Final Report, Example 1.28).

Differences in valuation of payments not relevant

5.19 A borrower in a foreign currency loan will generally have a foreign currency gain or loss with respect to the loan. Assuming the loan is in the currency of the lender’s residence, the lender will have no corresponding gain or loss. If the borrower has a loss, the loss is not thereby denied under the hybrid mismatch rules (Final Report, Example 1.17). The situation would be the same if the loan were in a third currency, even if currency movements mean there is a foreign exchange loss to one party and a foreign exchange gain to the other.

5.20 However, differences in valuation that lead to different characterisations of a payment may lead to Recommendation 1 applying – see Final Report Example 1.16, relating to an optional convertible note.

Timing differences

5.21 Where the payer and payee under a financial instrument are in different jurisdictions, it is not uncommon for them to recognise income/expenditure from the instrument on different bases. For example, a payer may be entitled to a deduction for a payment on an accrual basis, whereas a payee is taxable on a cash basis. In that case, there is a hybrid mismatch, which is prima facie subject to Recommendation 1.

5.22 The Final Report suggests[45] that a deduction should not be denied if the payment giving rise to the deduction is included in income in an accounting period that begins within 12 months of the end of the period in which the deduction is claimed. If this test is not met, the payer should still be entitled to a deduction if it can satisfy the tax authority that there is a reasonable expectation that the payment will be made within a reasonable period of time, and once made will be included in ordinary income. A reasonable period is one that might be expected to be agreed between arm’s length parties. Final Report Example 1.21 applies these principles.

5.23 The Final Report does not provide for any denied deductions to be carried forward and allowed if and when the payee does recognise income.

5.24 The UK appears to have adopted this approach, along with a provision that if a supposition ceases to be reasonable, consequential adjustments can be made.

5.25 The Australian Board of Taxation Report recommends a different approach. It suggests that a gap of up to three years between deduction and inclusion should not attract operation of the rule, whereas a longer gap should mandatorily do so. It also suggests that any deduction denial should reverse when and if the payee recognises the corresponding income. This is essentially a carry-forward loss proposal. The proposal seems to mirror what would happen in the case of inclusion under the defensive rule. If the amount of a deduction in a payer jurisdiction were included in the payee’s income under the defensive rule, and the payment giving rise to the income inclusion was later received, it would not be appropriate to tax the payment again, and rules against double taxation would generally achieve this. This supports the Board of Taxation carry-forward proposal in relation to the primary rule.

Taxation under other countries’ CFC rules

5.26 When a payment gives rise to a D/NI outcome, tax may still be imposed on the payment under a CFC regime. In this case the tax would be imposed on the owners of the payee, by the owner country. This is discussed at paragraph 36 and following of the Final Report. The Report gives countries the choice as to whether to treat CFC inclusion as taxation of the payee. This would be relevant for a New Zealand taxpayer in:

- determining whether to apply the primary response – in this case the New Zealand payer would need to establish that the payment made by it was subject to tax in the hands of the payee’s owners under a CFC regime; or

- determining whether or not to apply the secondary response – in this case the New Zealand payee would need to establish that the payment made to it was subject to tax in the hands of the payee’s own owners under a CFC regime.

5.27 The Report also says that a taxpayer seeking to rely on CFC inclusion should only be able to do so if it can satisfy the tax authority that the payment has been fully included under the laws of the CFC country. Unlike the general approach in Recommendation 1, this will require proof of actual taxation of the amount.

Application of rule to transfers of assets

5.28 Recommendation 1 generally does not apply to amounts paid for the transfer of an asset. However, transfers can give rise to hybrid mismatches in three different situations.

Portion of purchase price treated as payment under a financial instrument

5.29 First, there may be a hybrid mismatch in a cross-border asset sale if one or other country treats a portion of the purchase price of any asset as attributable to a financial instrument (see Example 1.27 of the Final Report). For example, if a purchaser is prima facie entitled to a deduction for a portion of a deferred purchase price under the financial arrangement rules, but the non-resident related party vendor treats the entire amount as purchase price, the hybrid financial instrument rule will deny the purchaser a deduction. Because the application of the rules depends on the tax treatment of a payment for a taxpayer of ordinary status, the linking rule will apply to deny a deduction even if the non-resident vendor is a trader and treats the purchase price as income for purposes of its home country taxation (Example 1.29 of the Final Report).

5.30 The Final Report also states that when a person is entitled to a deduction for a payment only because the person holds an asset on revenue account, and the person is fully taxable on their economic gain or loss from the asset, that deduction should not be denied by the linking rule (see Final Report paragraph 52 and Example 1.28). So if the purchaser in the previous paragraph is entitled to a deduction for a payment because it is a trader, that deduction should not be denied.

Hybrid transfers

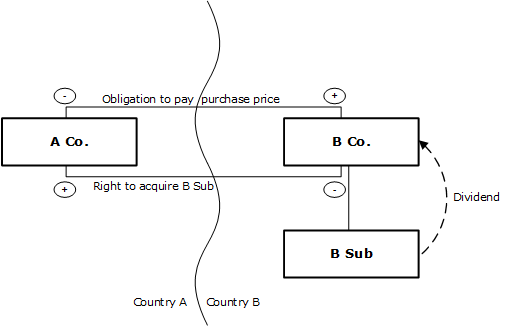

5.31 A second way the hybrid financial instrument rule can apply to a transfer of an asset is if it is a hybrid transfer. A hybrid transfer is a transaction, such as a share loan or a share repo, where the transferor and transferee are both treated as the owner of a financial instrument. This is usually because the terms of the transfer require both that the asset, or an identical asset, is returned to the transferor, and also that the transferor is compensated by the transferee for any income from the asset that arises during the term of the arrangement (whether or not received by the transferee). This means that economic risk on the asset remains with the transferor throughout the period from the initial transfer through to the retransfer. An example of a hybrid transfer is given in Figure 2.2 in Chapter 2 of this document, which is repeated here for convenience. Further examples are the transactions that were the subject of BNZ Investments Ltd v CIR (2009) 24 NZTC 23,582 and Westpac Banking Corporation v CIR (2009) 24 NZTC 23,834.

Figure 5.2: Hybrid transfer – share repo (repeated Figure 2.2)

5.32 New Zealand is generally a form country, so in Figure 2.2, if B Co (the share borrower) is a New Zealand company it will be treated as owning the B Sub shares, and deriving a dividend from B Sub, rather than as having lent money to, and deriving a financing return from, A Co. However, because Country A is a substance country, A Co is treated as owning the B Sub shares, receiving the dividend, and making a deductible financing payment to B Co, equal to the amount of the dividend. Accordingly, if Country A does not have hybrid rules, and A Co and B Co are either related parties or the repo is a structured arrangement, then the effect of the hybrid transfer rule is that B Co will have to recognise additional income, unless it is taxable on the dividend from B Sub with no imputation credits.

5.33 In the case of a share loan which is a hybrid transfer, the hybrid mismatch will generally arise because:

- the manufactured dividend payment made by the share receiver to the share supplier in the substance country is treated in the same way as a dividend in the share supplier country, which will often be exempt;

- the same payment will often be deductible to the share receiver in its country.

Substitute payments

5.34 The third situation in which the hybrid financial instrument rule can apply to a transfer of a financial instrument is if the transfer involves a “substitute payment” (as defined). A substitute payment is a payment under a transfer of a financial instrument which represents a financing or equity return on the underlying instrument and which undermines the integrity of the hybrid rules. This will be the case if the underlying payment (that is, the one that gives rise to the substitute payment):[46]

- is not included in the income of the substitute payer;

- would have been included in the income of the substitute payee; and

- gives rise to a hybrid mismatch.

5.35 In any of these circumstances, if the substitute payment gives rise to a hybrid mismatch, the hybrid rules will deny a deduction to the payer (primary response) or tax the payee (secondary response).

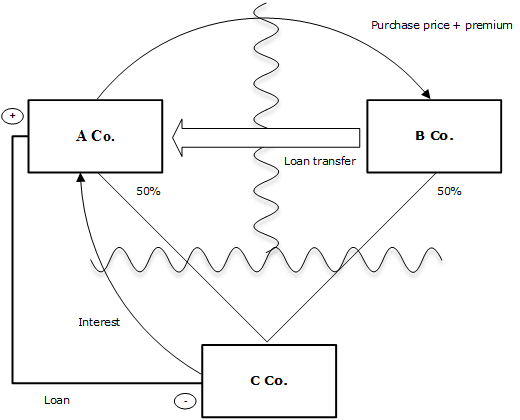

5.36 Example 1.36 of the Final Report shows a substitute payment, and is reproduced below.

Figure 5.3: Deduction for premium paid to acquire a bond with accrued interest[47]

5.37 The substitute payment is the premium portion of the amount paid by A Co to B Co for the transfer of the bond with accrued interest. The transfer is neither a financial instrument, nor a hybrid transfer. However, the premium is a payment in substitution for the payment of the accrued interest. It is deductible to A Co and treated as a capital gain to B Co, so it gives rise to a hybrid mismatch. On the facts of the example, the payment by A Co to B Co is a substitute payment because the payment of the coupon to the vendor would itself have given rise to a hybrid mismatch. The result would be the same if the coupon payment were taxable to the vendor. Accordingly, if the purchaser and vendor are related, or the sale is a structured arrangement, the payment of the premium will be subject to the hybrid mismatch rule.

Regulatory capital

5.38 The Final Report gives countries the option to exclude regulatory capital from their hybrid rules. A typical example is when the parent company in a multinational banking group issues regulatory capital instruments to the market for the purpose of using the funds to provide regulatory capital to a bank subsidiary in another country. Countries are free to exclude the intra-group regulatory capital from the hybrid rules. The Final Report also states that an exclusion of bank regulatory capital from one country’s rules does not require any other country with hybrid rules to refrain from applying them to regulatory capital instruments between the two countries.

Other exclusions

5.39 Recommendation 1.5 provides an exception to the primary response for investment vehicles that are subject to special regulatory and tax treatment that:

- is designed to ensure that while the vehicle itself has no tax liability, its investors have a liability, arising at more or less the same time as the gross investment income was derived by the investment vehicle; and

- ensures that all or substantially all of the vehicle’s investment income is paid and distributed to the owners within a reasonable period after the income is earned; and

- taxes the owners on the payment as ordinary income.

5.40 An example is a regulated real estate investment trust, which is entitled to a dividend paid deduction but required to pay out all of its earnings on a current year basis.

Application to New Zealand

5.41 A number of issues are worthy of further discussion and submission as to how Recommendation 1 could be incorporated into New Zealand law.

Applying the secondary rule to hybrid dividends

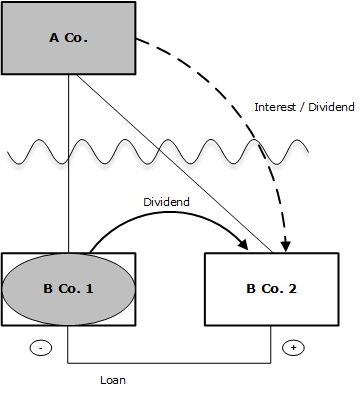

5.42 In New Zealand’s case, the secondary rule (taxation of amounts that are deductible in the payer jurisdiction) will also require the denial of imputation credits attached to a dividend which is deductible in another jurisdiction. This could arise in the situation set out in Example 1.23 of the Final Report, reproduced below, where New Zealand is Country B.

Figure 5.4: Payment by a hybrid entity under a hybrid financial instrument[48]

5.43 Accordingly, the Government proposes to amend the law so that imputation credits attached to a dividend on a hybrid financial instrument are not included in a New Zealand shareholder’s income and do not give rise to a tax credit. This non-inclusion would not affect the paying company. This ensures that application of the rule does not allow two lots of imputation credits to exist for what is in reality the same income. Denial of one amount of imputation credits correlates with the fact that the dividend payment has given rise to a foreign tax benefit.

5.44 As this example makes clear, implementing the defensive rule in Recommendation 1 will also require New Zealand to tax intra-group dividends that give rise to a hybrid mismatch under the hybrid financial instrument rule, even if these are between members of a 100 percent commonly owned group (whether or not consolidated).

Submission point 5B

Submissions are sought on whether there are any issues with the proposed approach in applying the secondary rule to hybrid dividends.

Timing mismatches

5.45 With respect to timing mismatches, the Australian Board of Taxation approach (see earlier paragraph 5.25) may have advantages for New Zealand. Denial of deductions (with carry forward) where there is a deferral of recognition of the corresponding income for more than three years:

- applies or not based on objective criteria which can be applied on a self-assessment basis, that is, without the need for the Commissioner to exercise any discretion; and

- seems both economically appropriate and consistent with the application of the secondary rule.

Submission points 5C

Submissions are sought on:

- whether the approach recommended by the Australian Board of Taxation would be an acceptable one for New Zealand;

- what alternatives might be better to deal with timing mismatches; and

- what thresholds should apply to determine when the rule would apply to a difference caused by different income and expenditure recognition rules.

Effect of CFC inclusion on application of Recommendation 1

5.46 The need to treat CFC taxation of a payee’s owner to be treated as taxation of the payee itself is not pressing in the case of the secondary response. Taxation of the payee in the payee country under the defensive rule is likely to simply reduce CFC taxation in the owner country.

5.47 Given the complexity of establishing the extent to which taxation under a CFC regime should be treated as inclusion for purposes of the hybrid rules, the fact that there is no need to do so when applying the secondary response, and the fact that there are usually alternatives to the use of hybrid instruments, it is not proposed to treat CFC taxation as relevant in applying Recommendation 1.

Submission point 5D

Submissions are sought on whether this approach as to CFC inclusion will give rise to any practical difficulties.

Taxation of FIF interests

5.48 If a New Zealand resident holds shares subject to the FIF regime, and accounts for those shares using the fair dividend rate (FDR), cost or deemed rate of return (DRR) method, the dividends on those shares are not taxable. Instead the resident returns an amount of deemed income. Dividends are only taxable if the holder uses the comparative value (CV) or attributable foreign interest (AFI) method (note that when those two methods are being used, if the dividend is deductible in the foreign country it will not be exempt in New Zealand even if the shareholder is a company).

5.49 FIF taxation therefore presents at least two problems for applying Recommendation 1.

- The non-resident payer of a deductible dividend to a New Zealand payee, if resident in a country with the hybrid rules, will not know how a New Zealand taxpayer of ordinary status would treat the dividend, and therefore will not know whether, or to what extent, it is denied a deduction for the dividend by the primary response in its own country.

- When the New Zealand payee is applying the defensive rule (in a case where the non-resident payer of a deductible dividend has not been denied a deduction), if the payee is not applying the CV or AFI method, the payee will need to determine how much of the dividend has not been taxed, in order to know how much additional income to include.

5.50 Possible solutions are to:

- deny the FDR, cost and DRR methods to shares on which any dividend would be deductible to the payer. This would be similar to the existing requirement to use the CV method for a non-ordinary (generally, debt-like) share (section EX 46(8));

- include a deductible dividend in the holder’s income, in addition to income already recognised under the FDR, cost or DRR method. This would be similar to the exclusion of deductible dividends from the general exemption for foreign dividends received by New Zealand companies in section CW 9 (though this exclusion does not apply to interests accounted for under the FDR, DRR or cost method);

- include a deductible dividend in the holder’s income only to the extent that it exceeds the income otherwise recognised on the shares. This is somewhat similar to the concept of a top-up amount (defined in section EX 60) that applies when a person uses the DRR method.

5.51 As long as one of these solutions is adopted, there should be no need for a non-resident payer of a deductible dividend to a New Zealand payee to apply the primary response.

Submission point 5E

Submissions are sought on which of these FIF approaches would be preferable and why, and whether there is another better approach.

Transfers of assets: revenue account holders

5.52 Recommendation 1 could apply to an asset transfer involving a New Zealand party. For example, suppose a New Zealand resident purchases an asset from a related party on deferred payment terms, and is entitled to deduct a portion of the price as financial arrangement expenditure. If the vendor treats the entire amount as being from the sale of the asset, then there will be a hybrid mismatch, and the purchaser will be denied a deduction for the expenditure.

5.53 The treatment if the New Zealand resident is acquiring the asset on revenue account (for example, because it is a trader), is less clear. As set out above, the Final Report states that where a person is entitled to a deduction for a payment only because the person holds an asset on revenue account, and the person is fully taxable on their economic gain or loss from the asset, that deduction should not be denied by the linking rule.

5.54 However, revenue account holders are not entitled to include in the cost of trading stock the element of their purchase price which is treated as financial arrangement expenditure (section EW 2(2)(d)). The denial of a deduction for that expenditure under the linking rule would not include it in the cost of trading stock. Also, non-taxation of income (for example, dividends on shares accounted for under the FDR method) is not turned off for revenue account holders. So, it is not the case that revenue account holders are always subject to income tax on all of their economic income.

5.55 Given that New Zealand does not tax revenue account holders on the basis referred to in paragraph 52 of the Final Report (referred to above), it is not proposed to exempt revenue account payers from the effect of the hybrid rule.

Submission point 5F

Submissions are sought as to whether revenue account holders should have an exemption from the rules.

Transfers of assets: hybrid transfers

5.56 New Zealand does have some specific tax rules for share loans and repos (the rules applying to returning share transfers and share lending arrangements, both as defined in the Income Tax Act 2007). Generally, these do not treat the share supplier as continuing to own the shares (though there is an exception for returning share transfers when the share supplier uses the FDR method to determine its income from foreign shares).[49] The closest they come is that in relation to a share lending arrangement the share supplier is treated as owning a share lending right for the period of the arrangement.

5.57 As referred to above, New Zealand has unique rules relating to the taxation of dividends on foreign shares. While dividends from ASX listed shares are generally taxable, other dividends on foreign shares may or may not be taxable.

5.58 Again, the New Zealand tax regime creates a difficulty for both counterparty countries (in this case, the country where the repo or share loan counterparty is resident, rather than where the share issuer is resident) and for New Zealand. Again, it would be possible to solve these issues by having a rule which would ensure that dividends paid on foreign shares to a New Zealand person who is party to a hybrid transfer with respect to the shares are always taxable, applying one of the approaches referred to in paragraph 5.50. The taxation of dividends paid on New Zealand shares held by a New Zealand share receiver who is a party to a hybrid transfer would be unchanged, unless the defensive rule was applied. In that case, the dividends would be taxable with no credit for any imputation credits on the dividends (see Final Report, Example 1.32).

Submission point 5G

Submissions are sought on whether this proposal for amending the income tax treatment of a New Zealand resident who holds shares subject to a hybrid transfer would be a practical response.

Regulatory capital

5.59 The UK proposes to take up the option to exclude bank regulatory capital instruments from its regime in certain circumstances (see discussion at Chapter 8 of Tackling aggressive tax planning (HM Treasury and HMRC, December 2014). However, we understand that the UK has existing anti-hybrid rules that apply to bank regulatory capital. The Australian Board of Taxation Report sought an extension of time to report on this issue.

5.60 It is not proposed that bank regulatory capital is excluded from the implementation of hybrid mismatch rules in New Zealand.

Submission point 5H

Submissions are sought on whether there are any issues with providing no exclusion for regulatory capital.

5.61 The exemption of an instrument from the hybrid rules in one country does not require exemption of that same instrument by others (Final Report, page 11). A decision by a country not to fully implement the rules is not intended to bind other countries in their own implementation. That is true even in an area where non-implementation is an option provided by the Final Report. Whether it is intended or not, a hybrid mismatch causes the same loss of overall tax revenue, and gives rise to the same difficulties of attributing that loss.

Other exclusions

5.62 We note that the UK legislation proposes an exception for hybrid transfers to which a financial trader is a party (section 259DD).[50] The Board of Taxation has recommended that consideration be given to an exception for financial traders entering into repos and securities-lending agreements. It is not clear that sufficient activity of this kind is taking place to justify an exception of this kind in New Zealand.

Submission point 5I

Submissions are sought on whether such an exception is necessary or desirable, and how it should be designed.

5.63 New Zealand does not seem to have any entities requiring an exception under Recommendation 1.5 from the primary response. In particular, PIEs are not entitled to a deduction for their distributions, and are not required to distribute their income within any period.

Submission point 5J

Submissions are sought on whether there are any other New Zealand entities that should be eligible for this exemption.

5.64 Finally, although the main target of the rule is cross-border transactions, the OECD recommendations can also apply to payments within a country (see Final Report, Examples 1.13 and 1.21). This means that the hybrid financial arrangement rule might deny deductions in purely domestic transactions in some circumstances. However, the focus of the hybrid mismatch rules should be on cross-border activity and accordingly it is proposed that domestic transactions are specifically excluded from the application of the rules.

42 The FITC regime involves a credit triggered by a dividend payment. However, this credit is used to satisfy the shareholder’s withholding tax obligation, so is not equivalent to a partial deduction – see para 13 of Example 1.11, OECD 2015 Final Report.

43 OECD 2015 Final Report, Example 2.1, at p279.

44 OECD 2015 Final Report, Example 1.25.

46 OECD 2015 Final Report at para 79.

47 OECD 2015 Final Report, Example 1.36, at p274.

48 OECD 2015 Final Report, Example 1.23, at p235.

49 See sections EX 52(14C) and EX 53(16C), Income Tax Act 2007.

50 Section 259DD of Schedule 10 of the Finance (No.2) Bill (United Kingdom).